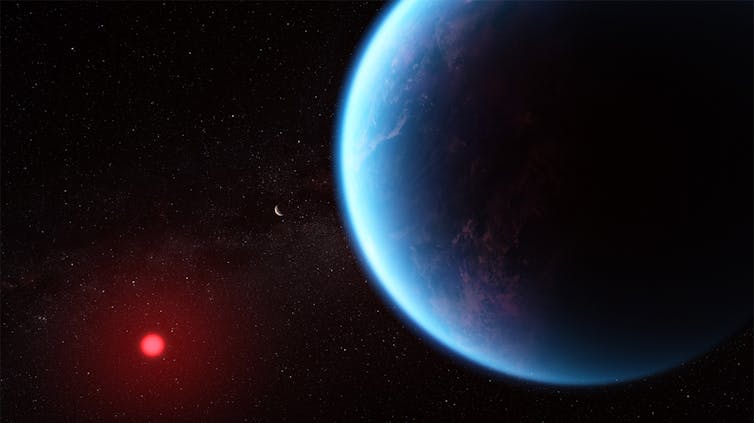

call on the Israeli government to secure the release of the hostages during a Jan. 15, 2025, protest.

Jack Guez/AFP via Getty Images)

Asher Kaufman, University of Notre Dame

A much-anticipated Gaza ceasefire and hostage deal is set to take effect on Jan. 19, 2025 – subject to an Israeli government vote on the package scheduled for the morning of Jan. 16.

The breakthrough comes 15 months into the bloody conflict sparked by an Oct. 7 2023, attack by Hamas gunmen in which about 1,200 Israelis were killed and 251 hostages taken. In the subsequent bombing and siege of the Gaza Strip, some 45,000 Palestinians have been killed.

But why has the breakthrough happened now, and what does this mean for the long-term prospects of a more permanent peace? The Conversation turned to Asher Kaufman, an expert on Israeli history and professor of peace studies at University of Notre Dame, for answers.

What is the main content of the deal?

Not all the details have been ironed out or released. But what we do know is this:

The deal is divided into three stages. In the first stage, 33 women, children and men who are sick or over the age of 55 will be released in stages over 42 days. The hostages, thought to have been held by Hamas in its network of tunnels under Gaza since Oct. 7, include two American nationals. In total, 94 hostages remain in captivity, including 34 thought to be dead.

The Israeli military will also allow Palestinians forced to leave northern Gaza to return, although much of the area and their homes are in complete ruins.

On the 16th day of implementation, negotiations will begin regarding the next stage of the deal, which will include the release of the remaining hostages taken by Hamas. As part of this stage, Israel will withdraw its forces to a defensive belt that will serve as a buffer between the Gaza Strip and Israel.

Ashraf Amra/Anadolu via Getty Images

In exchange for freeing the hostages, Israel will release Palestinian prisoners according to an agreed-upon ratio for each Israeli dead or living civilian or soldier hostage. In the initial wave, hundreds of Palestinian women and children currently held in Israeli prisons will be freed. Also, Israel will allow more humanitarian assistance to flow into Gaza.

The third stage of the deal will include the release of the remaining dead hostages and will focus on the reconstruction of Gaza supervised by Egypt, Qatar and the United Nations. At this stage, Israel will be expected to fully withdraw from the Gaza Strip.

How significant is the breakthrough?

Fifteen months of war has devastated Gaza. This deal opens the possibility of ending the fighting there and could allow for the first steps toward reconstruction and stabilization in the Palestinian enclave.

It could also allow the incoming Trump administration to focus on other issues that are more central to its foreign policy agenda, such as a potential new deal with Iran and the resumption of normalization talks between Israel and Saudi Arabia, connected to the creation of a new security alliance with the U.S.

For Israel, it means the possibility of an end to its longest war, which has cost a fortune, eroded its international standing and severely divided its society between supporters and opponents of the government. It could end the state of emergency that has been in effect since Oct. 7, 2023, allowing Israeli society to begin its own recovery.

What issues remain outstanding?

There are big question marks over the later stages of the deal. Important members of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s coalition, including Minister of National Security Itamar Ben-Gvir and Minister of Finance Bezalel Smotrich, have been accused of being more interested in a permanent occupation of the Gaza Strip than in the release of the hostages. As such, they will be loath to agree to any measures that would lead to a handing over of governance and security in the enclave to Palestinians.

Throughout the conflict, the Israel government has made it clear that it envisions no role for Hamas in a post-conflict Gaza. But Hamas’ main rival, the Palestinian Authority, has little credibility among Gaza’s residents. It leaves a gaping question of who will govern in Gaza.

There is also concern that if Israel was genuinely interested in full implementation of the deal, it could have reached an agreement that includes the complete withdrawal from Gaza in return for release of all hostages, rather than an agreement implemented in stages.

Why did talks succeed now, but earlier attempts fail?

This deal has been on the table at least since May 2024. But Netanyahu and his government have opposed it due mainly to their desire that Israel remain in control of Gaza.

Some of his government ministers also want to establish Jewish settlements in the Gaza Strip and have explicitly spoken about creating the conditions for reducing the numbers of Palestinians in the strip.

Critics of Netanyahu have also suggested that the prime minister wanted to prolong the war as long as possible because it served him politically.

But the entry of Donald Trump into the equation after his election as U.S. president changed the dynamics between Israel, Hamas and the U.S.

Trump wants to be seen as a deal-maker on the global stage, and Netanyahu – a close ally of the Republican – feels inclined to help Trump on this matter. The timing of the deal allows Trump to claim a role, while also allowing Joe Biden to leave office with a foreign policy “win.”

Hazem Bader/AFP via Getty Images)

There are also hopes in Israel that forging a deal now clears the way for the resumption of normalization talks between Israel and Saudi Arabia – a process kick-started under Trump’s first administration.

Netanyahu may be betting on a deal with Saudi Arabia to balance out his tarnished reputation at home as the Israeli leader in control when the Oct. 7 massacre occurred.

How will the deal play out in Israel’s fractious politics?

This is the big question that will determine the fate of the deal in the long term.

Its provisions contradict fundamentally the aspirations of many members in Netanyahu’s ruling coalition – and they may do the best they can to sabotage it.

It is still not clear if these right-wing holdouts will exit the government or stay in the coalition under the belief that the latter phases of the deal are not going to be implemented.

What does it mean for the future of Hamas and its role in Gaza?

The agreement does not specify conditions to replace Hamas’ rule in Gaza.

Netanyahu has so far objected to any efforts to facilitate the return of the Palestinian Authority or allow any other Arab or international consortium to run civilian affairs in the strip.

Hamas, for its part, has no interest in facilitating its replacement by other governing bodies and ceding control of Gaza. But having lost key members of its leadership over the course of the war, the militant group is in a less powerful position than it was before Oct. 7.

A cynical view might be that having a weakened Hamas remain in power may actually serve Netanyahu’s interests, allowing him to manage the Israeli-Palestinian conflict rather than trying to resolve it. This had been his approach before Oct. 7, and there are no indications that it has changed.![]()

Asher Kaufman, Professor of History and Peace Studies, University of Notre Dame

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.