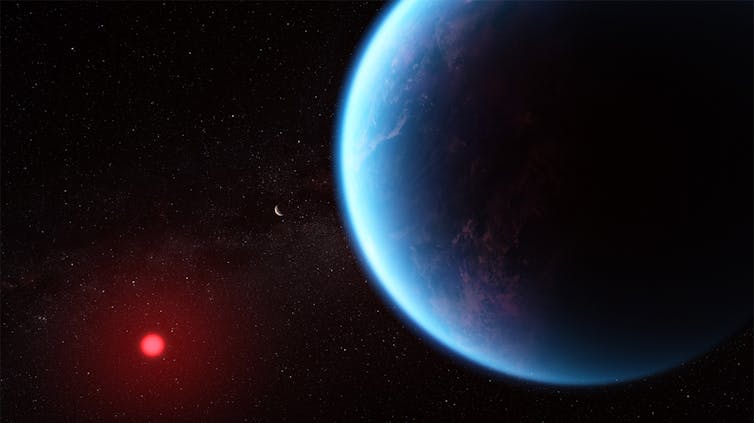

Some planets, such as Saturn, have more than a hundred moons, while others, such as Venus, have none.

Nicole Granucci, Quinnipiac University

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why do some planets have moons and some don’t? – Siddharth, age 6, Texas

On Earth, you can look up at night and see the Moon shining bright from hundreds of thousands of miles away. But if you went to Venus, that wouldn’t be the case. Not every planet has a moon – so why do some planets have several moons, while others have none?

I’m a physics instructor who has followed the current theories that describe why some planets have moons and some don’t.

First, a moon is called a natural satellite. Astronomers refer to satellites as objects in space that orbit larger bodies. Since a moon isn’t human-made, it’s a natural satellite.

Currently, there are two main theories for why some planets have moons. Moons are either gravitationally captured if they are within what’s called a planet’s Hill sphere radius, or they’re formed along with a solar system.

The Hill sphere radius

Objects exert a gravitational force of attraction on other nearby objects. The larger the object is, the greater the force of attraction.

This gravitational force is the reason we all stay grounded to Earth instead of floating away.

The solar system is dominated by the Sun’s large gravitational force, which keeps all of the planets in orbit. The Sun is the most massive object in our solar system, which means it has the most gravitational influence on objects such as planets.

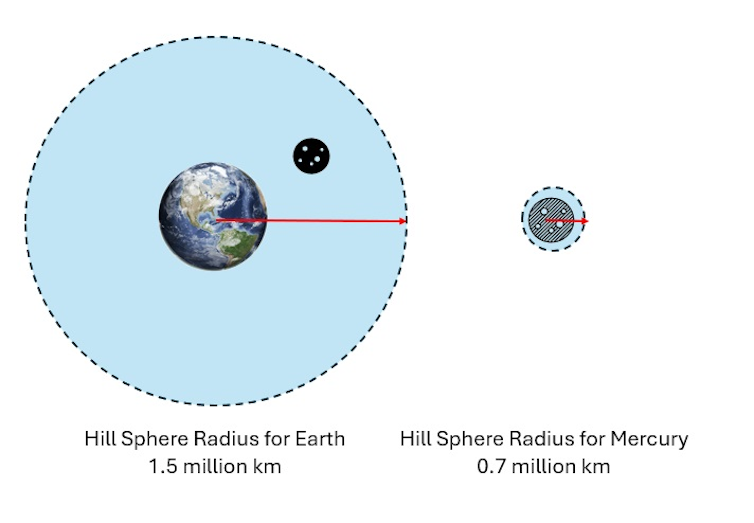

In order for a satellite to orbit a planet, it has to be close enough for the planet to exert enough force to keep it in orbit. The minimum distance for a planet to keep a satellite in orbit is called the Hill sphere radius.

The Hill sphere radius is based on the mass of both the larger object and the smaller object. The Moon orbiting Earth is a good example of how the Hill sphere radius works. The Earth orbits around the Sun, but the Moon is close enough to Earth that Earth’s gravitational pull captures it. The moon orbits around the Earth, rather than the Sun, because it is within Earth’s Hill sphere radius.

Earth has a larger Hill sphere radius than Mercury. Nicole Granucci

Small planets like Mercury and Venus have a tiny Hill sphere radius, since they can’t exert a large gravitational pull. Any potential moons would likely get pulled in by the Sun instead.

Many scientists are still looking to see whether these planets may have had small moons in the past. Back during the formation of the solar system, they may have had moons that got knocked away by collisions with other space objects.

Mars has two moons, Phobos and Deimos. Scientists still debate whether these came from asteroids that passed close into Mars’ Hill sphere radius and got captured by the planet, or if they were formed at the same time as the solar system. More evidence supports the first theory, because Mars is close to the asteroid belt.

Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune have larger Hill sphere radii, because they are much larger than Earth, Mars, Mercury and Venus and they’re farther from the Sun. Their gravitational pulls can attract and keep more natural satellites such as moons in orbit. For example, Jupiter has 95 moons, while Saturn has 146.

Moons forming with a solar system

Another theory suggests that some moons formed at the same time as their solar system.

Solar systems start out with a big disk of gas rotating around a sun. As the gas rotates around the sun, it condenses into planets and moons that rotate around them. The planets and moons then all rotate in the same direction.

But only a few moons in our solar system were likely created this way. Scientists predict that Jupiter’s and Saturn’s inner moons formed during the emergence of our solar system because they’re so old. The rest of the moons in our solar system, including Jupiter’s and Saturn’s outer moons, were probably gravitationally captured by their planets.

Earth’s Moon is special because it likely formed in a different way. Scientists believe that long ago, a large, Mars-sized object collided with the Earth. During that collision, a big chunk flew off the Earth and into its orbit and became the Moon.

Scientists guess that the Moon formed this way because they’ve found a type of rock called basalt in soil on the Moon’s surface. The Moon’s basalt looks the same as basalt found inside the Earth.

Ultimately, the question of why some planets have moons is still widely debated, but factors such as a planet’s size, gravitational pull, Hill sphere radius and how its solar system formed may play a role.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Nicole Granucci, Instructor of Physics, Quinnipiac University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.