Biases against certain groups of people can escalate into acts of violence if left unchecked.

Kristine Hoover, Gonzaga University and Yolanda Gallardo, Gonzaga University

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why do people hate people? – Daisy, age 9, Lake Oswego, Oregon

Have you ever said “I hate you” to someone? What about using the “h-word” in casual conversation, like “I hate broccoli”? What are you really feeling when you say that you hate something or someone?

The Merriam-Webster dictionary describes the word “hate” as an “intense hostility and aversion usually deriving from fear, anger, or sense of injury.” All over the world, researchers like us are studying hate from disciplines like education, history, law, leadership, psychology, sociology and many others.

If you had a scary experience with thunderstorms, you might say that you hate thunderstorms. Maybe you have gotten very angry at something that happened at a particular place, so now you say you hate going there. Maybe someone said something hurtful to you, so you say you hate that person.

Understanding hate as an emotional response can help you recognize your feelings about something or someone and be curious about where those feelings are coming from. This awareness will give you time to gather more information and imagine the other person’s perspective.

So what is hate and why do people hate? There are many answers to these questions.

What hate isn’t

Hate, according to the U.S. Department of Justice, “does not mean rage, anger or general dislike.”

Sometimes people think they have to feel or believe a certain way about another person or group of people because of what they hear or see around them. For example, people might say they hate another person or group of people when what they really mean is that they don’t agree with them, don’t understand them or don’t like how they behave or the things they believe in.

It is easy to blame others for things you don’t believe or experiences you don’t like. Think about times you might have heard someone at school say they hate a classmate or a teacher. Could they have been angry, hurt or confused about something but used the word hate to explain or name how they were feeling?

When you don’t understand someone else, it can make you nervous and even afraid. Instead of being curious about each other’s unique experiences, people may judge others for being different – they may have a different skin color, practice a different religion, come from a different country, be older or younger, or use a wheelchair.

When people judge people as being less important or less human than themselves, that is a form of hatred.

What hate is

The U.S. Department of Justice defines hate as “bias against people or groups with specific characteristics that are defined by the law.” These characteristics can include a person’s race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, disability and national origin.

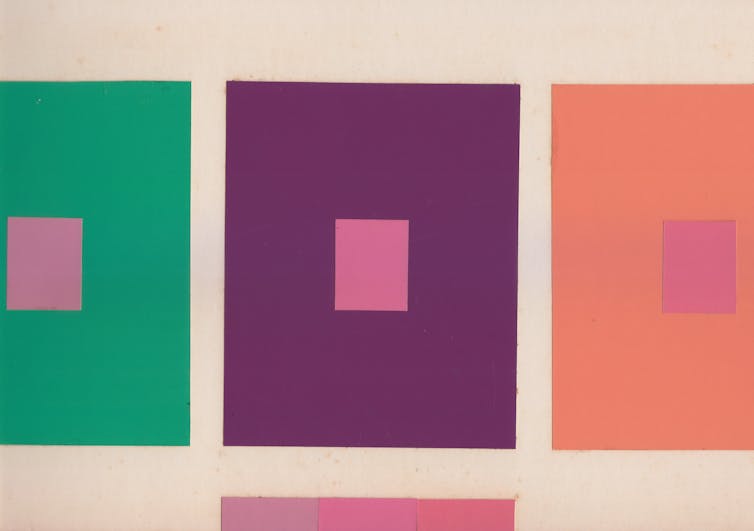

One way to think about hate is as a pyramid. At the bottom of the pyramid, hate is a feeling that grows from biased attitudes about others, like stereotypes that certain groups of people are animals, lazy or stupid.

Sometimes these biased attitudes and feelings provide a foundation for people to act out their biases, such as through bullying, exclusion or insults. For example, many Asian people in the U.S. experienced an increase in hate incidents during the COVID-19 pandemic. If communities accept biases as OK, some people may move up the pyramid and think it is also OK to discriminate, or believe that specific groups of people are not welcome in certain neighborhoods or jobs because of who they are.

Near the top of the pyramid, some people commit violence or hate crimes because they believe their own way of being is better than others’. They may threaten or physically harm others, or destroy property. At the very top of the pyramid is genocide, the intent to destroy a particular group – like what Jewish people experienced during World War II or what Rohingya people are experiencing today in Myanmar, near China.

Hate at the middle and higher levels of the pyramid happens because no one took action to discourage the biased feelings, attitudes and actions at the lower levels of the pyramid.

Taking action against hate

Not only can individual people hate, there are also hate groups like the Ku Klux Klan that attack people who are not white, straight or Christian. Sometimes hate has been written into law like the Indian Removal Act or Jim Crow laws that persecuted Native and Black Americans. If we stay silent when we encounter hate, that hatred can grow and do greater levels of harm.

There are many ways you can help stop hate in your everyday life.

Pay attention to what is being said around you. If the people you spend a lot of time with are saying hateful things about other groups, consider speaking up or changing who you hang out with and where. Be an upstander – sit with someone who is being targeted and report when you see or hear hate incidents.

Protests are one way people speak up on behalf of a specific group.

Start noticing when you are letting hateful words or behaviors into your thoughts and actions. Get to know what hate looks and sounds like in yourself and in others, including what you see online.

Be open to meeting others who have different experiences than you and give them a chance to let you know who they are. Be brave and face your fears. Be curious and kind.

You are not alone in standing up to hate. Many human rights groups and government initiatives are doing the work of eradicating hate, too. We all have a “response-ability,” or the ability to respond. As civil rights leader the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “Darkness cannot drive out darkness, only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate, only love can do that.”

You just might find that it is easier to love other people than to hate them. Others will see how you behave and will follow your lead.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Kristine Hoover, Professor of Organizational Leadership, Gonzaga University and Yolanda Gallardo, Dean of Education, Gonzaga University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.