Svetlozar Hristov/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Ambuj Tewari, University of Michigan

Microplastics – the tiny particles of plastic shed when litter breaks down – are everywhere, from the deep sea to Mount Everest, and many researchers worry that they could harm human health.

I am a machine learning researcher. With a team of scientists, I have developed a tool to make identification of microplastics using their unique chemical fingerprint more reliable. We hope that this work will help us learn about the types of microplastics floating through the air in our study area, Michigan.

Microplastics – a global problem

The term plastic refers to a wide variety of artificially created polymers. Polyethylene, or PET, is used for making bottles; polypropylene, or PP, is used in food containers; and polyvinyl chloride, or PVC, is used in pipes and tubes.

Microplastics are small plastic particles that range in size from 1 micrometer to 5 millimeters. The width of a human hair, for comparison, ranges from 20 to 200 micrometers.

Most scientific studies focus on microplastics in water. However, microplastics are also found in the air. Scientists know much less about microplastics in the atmosphere.

When scientists collect samples from the environment to study microplastics, they usually want to know more about the chemical identities of the microplastic particles found in the samples.

Anton Petrus/Moment via Getty Images

Fingerprinting microplastics

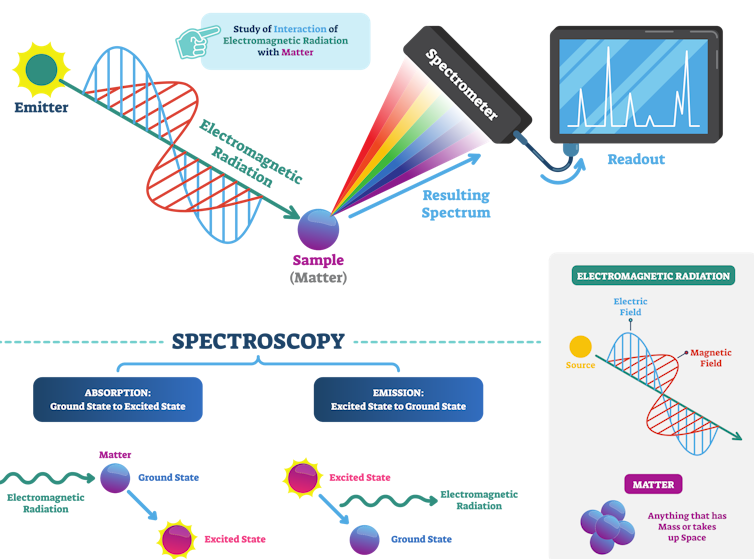

Just as fingerprinting uniquely identifies a person, scientists use spectroscopy to determine the chemical identity of microplastics. In spectroscopy, a substance either absorbs or scatters light, depending on how its molecules vibrate. The absorbed or scattered light creates a unique pattern called the spectrum, which is effectively the substance’s fingerprint.

VectorMine/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Just like a forensic analyst can match an unknown fingerprint against a fingerprint database to identify the person, researchers can match the spectrum of an unknown microplastic particle against a database of known spectra.

However, forensic analysts can get false matches in fingerprint matching. Similarly, spectral matching against a database isn’t foolproof. Many plastic polymers have similar structures, so two different polymers can have similar spectra. This overlap can lead to ambiguity in the identification process.

So, an identification method for polymers should provide a measure of uncertainty in its output. That way, the user can know how much to trust the polymer fingerprint match. Unfortunately, current methods don’t usually provide an uncertainty measure.

Data from microplastic analyses can inform health recommendations and policy decisions, so it’s important for the people making those calls to know how reliable the analysis is.

Conformal prediction

Machine learning is one tool researchers have started using for microplastic identification.

First, researchers collect a large dataset of spectra whose identities are known. Then, they use this dataset to train a machine learning algorithm that learns to predict a substance’s chemical identity from its spectrum.

Sophisticated algorithms whose inner workings can be opaque make these predictions, so the lack of an uncertainty measure becomes an even greater problem when machine learning is involved.

Our recent work addresses this issue by creating a tool with an uncertainty quantification for microplastic identification. We use a machine learning technique called conformal prediction.

Conformal prediction is like a wrapper around an existing, already trained machine learning algorithm that adds an uncertainty quantification. It does not require the user of the machine learning algorithm to have any detailed knowledge of the algorithm or its training data. The user just needs to be able to run the prediction algorithm on a new set of spectra.

To set up conformal prediction, researchers collect a calibration set containing spectra and their true identities. The calibration set is often much smaller than the training data required for training machine learning algorithms. Usually just a few hundred spectra are enough for calibration.

Then, conformal prediction analyzes the discrepancies between the predictions and correct answers in the calibration set. Using this analysis, it adds other plausible identities to the algorithm’s single output on a particular particle’s spectrum. Instead of outputting one, possibly incorrect, prediction like “this particle is polyethylene,” it now outputs a set of predictions – for example, “this particle could be polyethylene or polypropylene.”

The prediction sets contain the true identity with a level of confidence that users can set themselves – say, 90%. Users can then rerun the conformal prediction with a higher confidence – say, 95%. But the higher the confidence level, the more polymer predictions given by the model in the output.

It might seem that a method that outputs a set rather than a single identity isn’t as useful. But the size of the set serves as a way to assess uncertainty – a small set indicates less uncertainty.

On the other hand, if the algorithm predicts that the sample could be many different polymers, there’s substantial uncertainty. In this case, you could bring in a human expert to examine the polymer closely.

Testing the tool

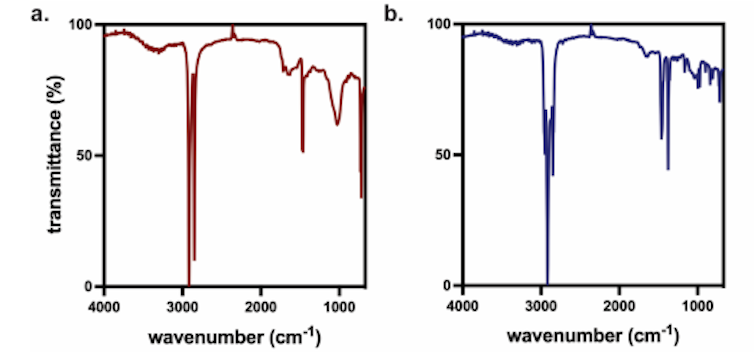

To run our conformal prediction, my team used libraries of microplastic spectra from the Rochman Lab at the University of Toronto as the calibration set.

Once calibrated, we collected samples from a parking lot in Brighton, Michigan, obtained their spectra, and ran them through the algorithm. We also asked an expert to manually label the spectra with the correct polymer identities. We found that conformal prediction did produce sets that included the label the human expert gave it.

Ambuj Tewari

Microplastics are an emerging concern worldwide. Some places such as California have begun to gather evidence for future legislation to help curb microplastic pollution.

Evidence-based science can help researchers and policymakers fully understand the extent of microplastic pollution and the threats it poses to human welfare. Building and openly sharing machine learning-based tools is one way to help make that happen.![]()

Ambuj Tewari, Professor of Statistics, University of Michigan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.