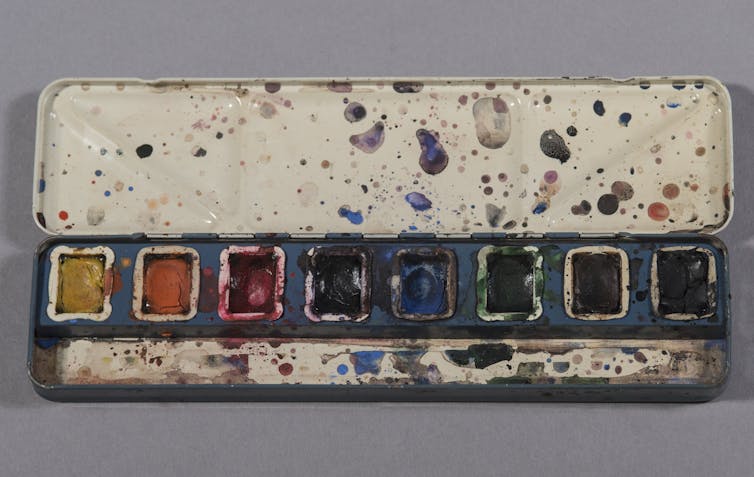

Konrad Jacobs (right) and Anonymous (left) via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Like most mathematicians, I hear confessions from complete strangers: the inevitable “I was always bad at math.” I suppress the response, “You are forgiven, my child.”

Why does it feel like a sin to struggle in math? Why are so many traumatized by their mathematics education? Is learning math worthwhile?

Sometimes agreeing and sometimes disagreeing, André and Simone Weil were the sort of siblings who would argue about such questions. André achieved renown as a mathematician; Simone was a formidable philosopher and mystic. André focused on applying algebra and geometry to deep questions about the structures of whole numbers, while Simone was concerned with how the world can be soul-crushing.

Both wrestled with the best way to teach math. Their insights and contradictions point to the fundamental role that mathematics and mathematics education play in human life and culture.

André Weil’s rigorous mathematics

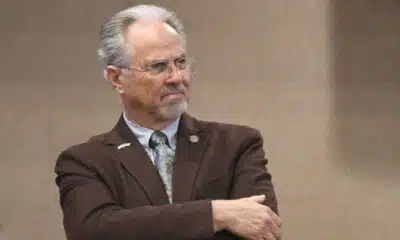

Konrad Jacobs via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Unlike the prominent French mathematicians of previous generations, André, who was born in 1906 and died in 1998, spent little time philosophizing. For him, mathematics was a living subject endowed with a long and substantial history, but as he remarked, he saw “no need to defend (it).”

In his interactions with people, André was an unsparing critic. Although admired by some colleagues, he was feared by and at times disdainful of his students. He co-founded the Bourbaki mathematics collective that used abstraction and logical rigor to restructure mathematics from the ground up.

Nicolas Bourbaki’s commitment to proceeding from first principles, however, did not completely encapsulate his conception of what constituted worthwhile mathematics. André was attuned to how math should be taught differently to different audiences.

Tempering the Bourbaki spirit, he defined rigor as “(not) proving everything, but … endeavoring to assume as little as possible at every stage.”

Unknown author via Wikimedia Commons

In other words, absolute rigor has its place, but teachers must be willing to take their audience into account. He believed that teachers must motivate students by providing them meaningful problems and provocative examples. Excitement for advanced students comes in encountering the unknown; for beginning students, it emerges from solving questions of, as he put it, “theoretical or practical importance.” He insisted that math “must be a source of intellectual excitement.”

André’s own sense of intellectual excitement came from applying insights from one part of mathematics to other parts. In a letter to his sister, André described his work as seeking a metaphorical “Rosetta stone” of analogies between advanced versions of three basic mathematical objects: numbers, polynomials and geometric spaces.

André described mathematics in romantic terms. Initially, the relationship between the different parts of mathematics is that of passionate lovers, exchanging “furtive caresses” and having “inexplicable quarrels.” But as the analogies eventually give way to a single unified theory, the affair grows cold: “Gone is the analogy: gone are the two theories, their conflicts and their delicious reciprocal reflections … alas, all is just one theory, whose majestic beauty can no longer excite us.”

Despite being passionless, this theory that unifies numbers, polynomials and geometry gets to the heart of mathematics; André pursued it intensely. In the words of a colleague, André sought the “real meaning of every basic mathematical phenomenon.” For him, unlike his sister, this real meaning was found in the careful definitions, precisely articulated theorems and rigorous proofs of the most advanced mathematics of his time. Romantic language simply described the emotions of the mathematician encountering the mathematics; it did not point to any deeper significance.

Simone Weil and the philosophy of mathematics

On the other hand, Simone, who was born three years after André and died 55 years before him, used philosophy and religion to investigate the value of mathematics for nongeniuses, in addition to her work on politics, war, science and suffering.

Anonymous via Wikimedia Commons

All of her writing – indeed, her life – has a maddening quality to it. In her polished essays, as well as her private letters and journals, she will often make an extreme assertion or enigmatic comment. Such assertions might concern the motivations of scientists, the psychological state of a sufferer, the nature of labor, an analysis of labor unions or an interpretation of Greek philosophers and mathematicians. She is not a systematic thinker but rather circles around and around clusters of ideas and themes. When I read her writing, I am often taken aback. I start to argue with her, bringing up counterexamples and qualifications, but I eventually end up granting the essence of her point. Simone was known for the single-minded pursuit of her ideals.

Despite the discomfort her viewpoints provoke, they are worth engaging. Although her childhood was largely happy, her whole life she felt stupid in comparison with her brother. She channeled her feelings of inadequacy into an exploration of how to experience a meaningful existence in the face of oppression and affliction. Over her life, she developed an interpretation of beauty and suffering intertwined with geometry.

Along with her lifelong mathematical discussions with André, her views were influenced by one of her first jobs as a teacher. In a letter to a colleague, she described her pupils as struggling because they “regarded the various sciences as compilations of cut-and-dried knowledge.” Like André, Simone saw the ability to motivate students as the key to good teaching. She taught mathematics as a subject embedded in culture, emphasizing overarching historical themes. Even those students who were “most ignorant in science” followed her lectures with “passionate interest.”

For Simone, however, the primary purpose of mathematics education was to develop the virtue of attention. Mathematics confronts us with our mistakes, and the contemplation of these inadequacies brings the ability to concentrate on one thing, at the exclusion of all else, to the fore. As a math teacher, I frequently see students grit their teeth and furrow their brow, developing only a headache and resentment. According to Simone, however, true attention arises from joy and desire. We hold our knowledge lightly and wait with detached thought for light to arrive.

For Simone, the “first duty” of teachers is to help students develop, through their studies, the ability to apprehend God, which she conceptualized as a blending of Plato’s description of the ultimate Good with Christian conceptions of the self-abnegating God. A true understanding of God results in love for the afflicted.

Simone might even locate the lingering anxiety and frustration of many former math students in the absence of attention paid to them by their teachers.

Authors grapple with the Weil legacy

Recently, others have wrestled with the Weil legacy.

Sylvie Weil, André’s daughter, was born shortly before Simone’s death. Her family experience was that of being mistaken for her aunt, ignored or demeaned by her father and not being acknowledged and appreciated by those in her orbit.

Similarly, author Karen Olsson uses Simone and André to explore her own conflicted relationship with mathematics. Her forlorn quest to understand André’s mathematics eerily reflects Simone’s desire to understand André’s work and Sylvie’s desire to be seen as her own person, to not be in Simone’s shadow. Olsson studied with exceptional math teachers and students, all the while feeling out of place, overwhelmed and intimidated by her fellow students. Most painfully, in the process of writing her book on the Weil siblings, Olsson asks a mathematician, who had been a student with her, for help in understanding some aspect of André’s mathematics. She was ignored. Both Sylvie Weil and Karen Olsson are living witnesses to Simone’s observation that each of us cries out to be seen.

Christopher Jackson, on the other hand, gives testimony to how mathematics can live up to Simone’s vision. Jackson is incarcerated in a federal prison but found a new life through mathematics. His correspondence with mathematician Francis Su is the backbone of Su’s 2020 book “Mathematics for Human Flourishing,” which uses Simone’s observation that “every being cries out silently to be read differently” as a leitmotif. Su identifies aspects of mathematics that promote human flourishing, such as beauty, truth, freedom and love. In their own ways, both Simone and André would likely agree.

Scott Taylor, Professor of Mathematics, Colby College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.