If you’ve spent any time scrolling through the health and wellness corners of social media, you’ve likely come across many products claiming to improve your metabolism. But what exactly is your metabolism?

Everything you expose your body to – from lifestyle to an airborne virus – influences your physical characteristics, such as your blood pressure and energy levels. Together, these biological characteristics are referred to as your phenotype. And the biological system that most directly influences your phenotype is your metabolism.

So if you are eating something, take medications, smoke or exercise, your metabolism is responsible for transferring that biological information throughout your body for it to adapt.

Metabolism is energy conversion

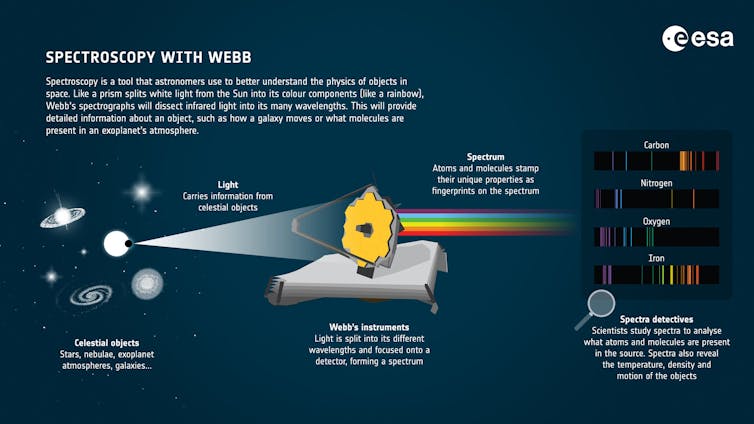

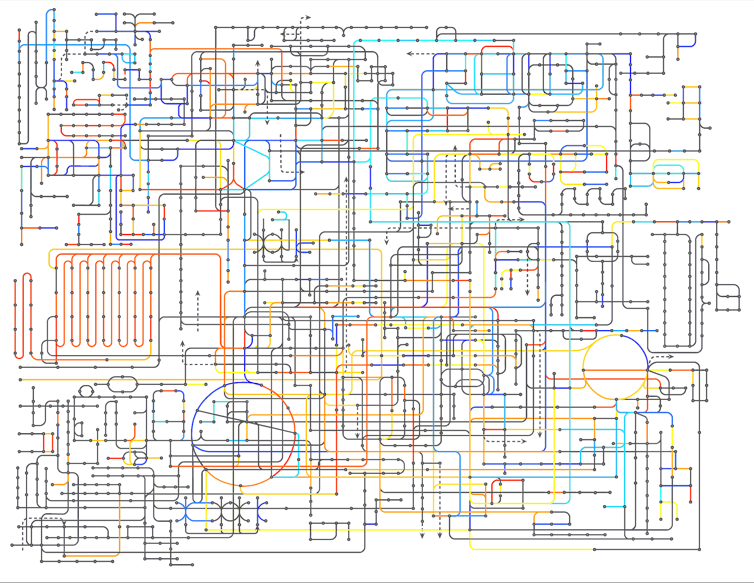

Your metabolism consists of a network of tens of thousands of molecules and proteins that convert the food you eat into the energy and building blocks your body uses to move, grow and repair itself. At the chemical level, energy metabolism begins when the three macronutrients – carbohydrates, fats and protein – are broken down atom by atom to release electrons from chemical bonds. These electrons charge components in cells called mitochondria.

Akin to how batteries work, mitochondria harness this electrical potential to create a different form of chemical energy that the rest of the cell can use.

Simply put, a primary role of metabolism is to convert chemical energy into electrical energy and back into chemical energy. How this energy is transferred throughout the body might play a central role in determining whether you’re sick or healthy.

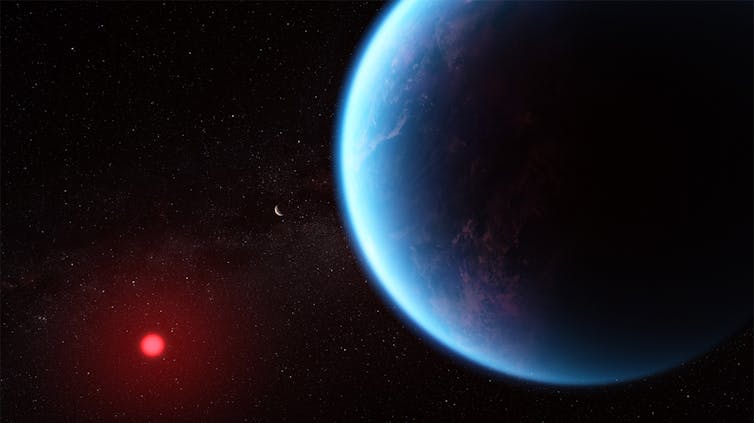

J3D3/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

I am a biochemist who studies the various networks of metabolism that are used as your body changes. My team and I have been able to define specific traits of metabolism, such as the presence and amount of certain metabolites – products made from breaking down macronutrients – across a wide range of conditions.

These conditions include diseases such as COVID-19, diabetes, multiple sclerosis and sickle cell anemia, to experiencing unique environments such as radiation exposure, high altitude, aging and sports performance. Each of these settings influences which parts of your metabolic network are used and how they communicate with one another.

Elite athletes define the upper limits

Given the alarming rise in obesity and its associated metabolic syndrome – about 1 in 8 people across the globe were living with obesity in 2022 – defining a healthy or impaired metabolism can help identify what’s gone wrong and how to address it.

Elite athletes offer a prime population to study metabolic function at its best, since their network of molecular and chemical reactions must be finely tuned to compete on the world stage.

Traditionally, lactate threshold has been a critical measure of athletic performance by pinpointing exercise intensity when lactate starts to rise in muscles and blood.

Contrary to common belief, lactate is not merely a waste product but an energy source as well, and it accumulates when it’s produced faster than mitochondria can use it. While a moderately active person might reach their threshold at an exercise intensity of around 2 watts per kilogram, elite cyclists can sustain an intensity up to nearly two to three times higher.

When comparing the lactate thresholds of a group of elite cyclists, we found that the cyclists with higher thresholds had markers of better mitochondrial function. One of these markers was higher production of coenzyme A, a molecule that shuttles carbon around cells and is important for breaking down carbs, amino acids and fat into chemical energy.

Higher-performing cyclists also appeared to burn more fat and burn fat longer during a multistage world tour compared with lower-performing cyclists.

Dysfunctional metabolism in diseases like COVID-19

Your metabolism also changes if you get an acute illness such as COVID-19.

In contrast to elite cyclists, COVID-19 patients have an impaired ability to burn fat that appears to persist with long COVID. The blood of these patients at rest is similar to that of an elite cyclist’s at exhaustion. Considering that exercise intolerance frequently occurs with long COVID, this suggests mitochondrial dysfunction may play a role in COVID-related fatigue.

Maria Korneeva/Moment via Getty Images

Burning fat uses a lot of oxygen. COVID-19 damages the red blood cells that deliver oxygen to organs. Because red blood cells have a limited ability to repair themselves, they might not function as well during the remainder of their roughly 120-day life span. This may partially explain why COVID symptoms last as long as they do in some people.

Blood donors define the middle

Blood transfusions are one of the most common clinical procedures. Over 118 million pints of blood are donated by millions of people worldwide every year. Because blood donors undergo screening to ensure they are healthy enough to donate, they are typically moderately healthy, somewhere between acute illness and elite athletic performance. Blood donors, coming from every walk of life, also have a diverse range of biological traits as a study population.

My team and I looked at blood from over 13,000 blood donors to shed light on their metabolic diversity. We found specific traits that could predict how well a donor’s blood would work in patients, which also has implications for how well that blood works in the donors themselves.

We found that one of these traits is a metabolite called kynurenine, which is produced from the breakdown of the amino acid tryptophan. We found that blood from donors with higher levels of kynurenine was less likely to restore hemoglobin levels in transfusion recipients compared with donors with lower kynurenine levels.

Kynurenine levels are higher in older donors and donors with a higher BMI, and may potentially be tied to higher levels of inflammation. In support, our group also found that kynurenine increases dramatically in runners participating in the 171-kilometer (106 miles) Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc. In addition, we also identified that kynurenine is a strong marker of COVID-19 severity.

The relationship between metabolites and health outcomes reinforces the important role metabolism plays in the body. Getting a better understanding of what healthy metabolism looks like can offer unique insights into how it deviates when someone gets sick and may offer new approaches to medical treatments.