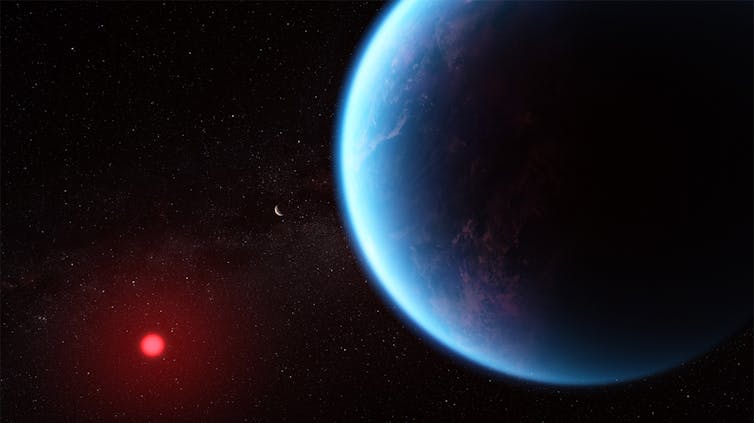

NASA, ESA, CSA, Joseph Olmsted (STScI)

Daniel Apai, University of Arizona

A team of astronomers announced on April 16, 2025, that in the process of studying a planet around another star, they had found evidence for an unexpected atmospheric gas. On Earth, that gas – called dimethyl sulfide – is mostly produced by living organisms.

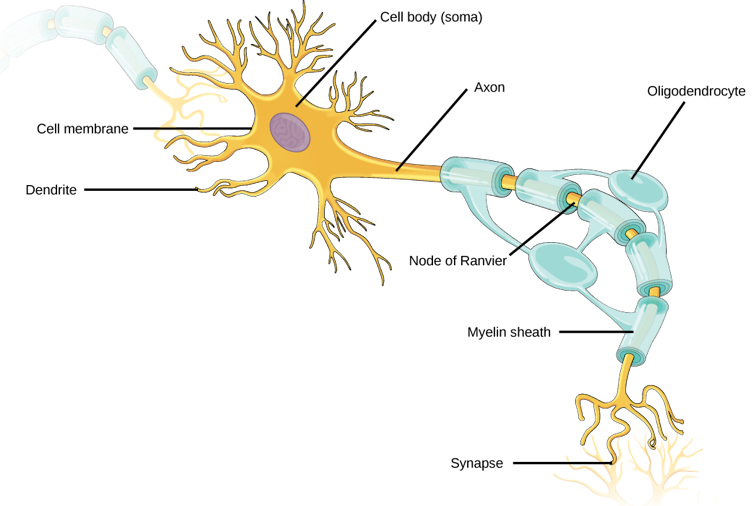

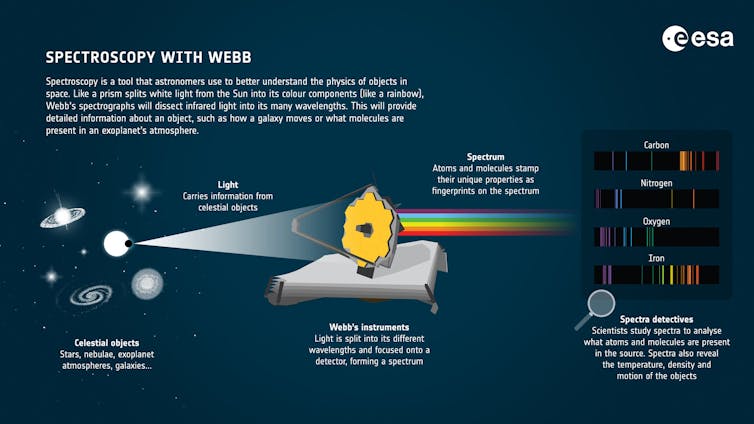

In April 2024, the James Webb Space Telescope stared at the host star of the planet K2-18b for nearly six hours. During that time, the orbiting planet passed in front of the star. Starlight filtered through its atmosphere, carrying the fingerprints of atmospheric molecules to the telescope.

European Space Agency

By comparing those fingerprints to 20 different molecules that they would potentially expect to observe in the atmosphere, the astronomers concluded that the most probable match was a gas that, on Earth, is a good indicator of life.

I am an astronomer and astrobiologist who studies planets around other stars and their atmospheres. In my work, I try to understand which nearby planets may be suitable for life.

K2-18b, a mysterious world

To understand what this discovery means, let’s start with the bizarre world it was found in. The planet’s name is K2-18b, meaning it is the first planet in the 18th planetary system found by the extended NASA Kepler mission, K2. Astronomers assign the “b” label to the first planet in the system, not “a,” to avoid possible confusion with the star.

K2-18b is a little over 120 light-years from Earth – on a galactic scale, this world is practically in our backyard.

Although astronomers know very little about K2-18b, we do know that it is very unlike Earth. To start, it is about eight times more massive than Earth, and it has a volume that’s about 18 times larger. This means that it’s only about half as dense as Earth. In other words, it must have a lot of water, which isn’t very dense, or a very big atmosphere, which is even less dense.

Astronomers think that this world could either be a smaller version of our solar system’s ice giant Neptune, called a mini-Neptune, or perhaps a rocky planet with no water but a massive hydrogen atmosphere, called a gas dwarf.

Another option, as University of Cambridge astronomer Nikku Madhusudhan recently proposed, is that the planet is a “hycean world”.

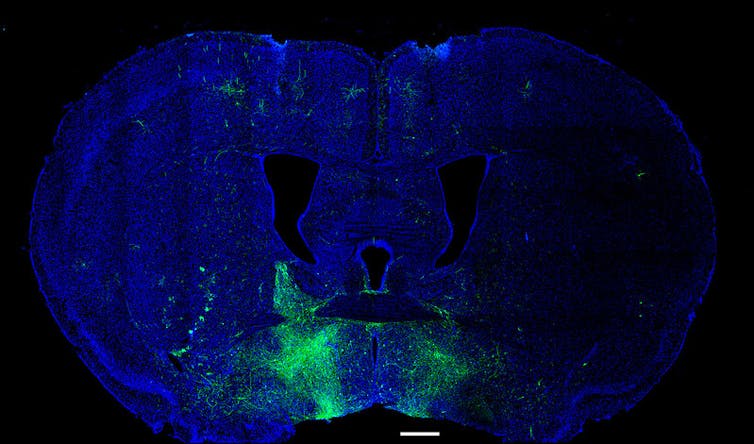

That term means hydrogen-over-ocean, since astronomers predict that hycean worlds are planets with global oceans many times deeper than Earth’s oceans, and without any continents. These oceans are covered by massive hydrogen atmospheres that are thousands of miles high.

Astronomers do not know yet for certain that hycean worlds exist, but models for what those would look like match the limited data JWST and other telescopes have collected on K2-18b.

This is where the story becomes exciting. Mini-Neptunes and gas dwarfs are unlikely to be hospitable for life, because they probably don’t have liquid water, and their interior surfaces have enormous pressures. But a hycean planet would have a large and likely temperate ocean. So could the oceans of hycean worlds be habitable – or even inhabited?

Detecting DMS

In 2023, Madhusudhan and his colleagues used the James Webb Space Telescope’s short-wavelength infrared camera to inspect starlight that filtered through K2-18b’s atmosphere for the first time.

They found evidence for the presence of two simple carbon-bearing molecules – carbon monoxide and methane – and showed that the planet’s upper atmosphere lacked water vapor. This atmospheric composition supported, but did not prove, the idea that K2-18b could be a hycean world. In a hycean world, water would be trapped in the deeper and warmer atmosphere, closer to the oceans than the upper atmosphere probed by JWST observations.

Intriguingly, the data also showed an additional, very weak signal. The team found that this weak signal matched a gas called dimethyl sulfide, or DMS. On Earth, DMS is produced in large quantities by marine algae. It has very few, if any, nonbiological sources.

This signal made the initial detection exciting: on a planet that may have a massive ocean, there is likely a gas that is, on Earth, emitted by biological organisms.

Amanda Smith, Nikku Madhusudhan (University of Cambridge), CC BY-SA

Scientists had a mixed response to this initial announcement. While the findings were exciting, some astronomers pointed out that the DMS signal seen was weak and that the hycean nature of K2-18b is very uncertain.

To address these concerns, Mashusudhan’s team turned JWST back to K2-18b a year later. This time, they used another camera on JWST that looks for another range of wavelengths of light. The new results – announced on April 16, 2025 – supported their initial findings.

These new data show a stronger – but still relatively weak – signal that the team attributes to DMS or a very similar molecule. The fact that the DMS signal showed up on another camera during another set of observations made the interpretation of DMS in the atmosphere stronger.

Madhusudhan’s team also presented a very detailed analysis of the uncertainties in the data and interpretation. In real-life measurements, there are always some uncertainties. They found that these uncertainties are unlikely to account for the signal in the data, further supporting the DMS interpretation. As an astronomer, I find that analysis exciting.

Is life out there?

Does this mean that scientists have found life on another world? Perhaps – but we still cannot be sure.

First, does K2-18b really have an ocean deep beneath its thick atmosphere? Astronomers should test this.

Second, is the signal seen in two cameras two years apart really from dimethyl sulfide? Scientists will need more sensitive measurements and more observations of the planet’s atmosphere to be sure.

Third, if it is indeed DMS, does this mean that there is life? This may be the most difficult question to answer. Life itself is not detectable with existing technology. Astronomers will need to evaluate and exclude all other potential options to build their confidence in this possibility.

The new measurements may lead researchers toward a historic discovery. However, important uncertainties remain. Astrobiologists will need a much deeper understanding of K2-18b and similar worlds before they can be confident in the presence of DMS and its interpretation as a signature of life.

Scientists around the world are already scrutinizing the published study and will work on new tests of the findings, since independent verification is at the heart of science.

Moving forward, K2-18b is going to be an important target for JWST, the world’s most sensitive telescope. JWST may soon observe other potential hycean worlds to see if the signal appears in the atmospheres of those planets, too.

With more data, these tentative conclusions may not stand the test of time. But for now, just the prospect that astronomers may have detected gasses emitted by an alien ecosystem that bubbled up in a dark, blue-hued alien ocean is an incredibly fascinating possibility.

Regardless of the true nature of K2-18b, the new results show how using the JWST to survey other worlds for clues of alien life will guarantee that the next years will be thrilling for astrobiologists.![]()

Daniel Apai, Associate Dean for Research and Professor of Astronomy and Planetary Sciences, University of Arizona

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.