News from the South - West Virginia News Feed

‘We’re drowning’: Teacher pay vs. cost of living approaches crisis level in WV’s Eastern Panhandle

‘We’re drowning’: Teacher pay vs. cost of living approaches crisis level in WV’s Eastern Panhandle

by Mike Chalmers, West Virginia Watch

March 10, 2025

The phrase “say the hard part out loud” has had a moment in the national spotlight recently. And within West Virginia, you’ll hear it repeatedly when you talk to education professionals in the Eastern Panhandle about teacher pay.

Something else you’ll hear with regularity is the word “crisis.”

Michelle Barnhart, a social studies teacher at Martinsburg’s South Middle School in Berkeley County, has seen the teacher shortage turn from a growing problem into something much more serious.

“When I started teaching in 2017, you had to be actively working on your degree to even be considered for a position. Now, they’re putting people with associate degrees — or no degree at all — into classrooms as full-time teachers,” she said. “They aren’t supposed to, but they have no choice.”

The state, added Barnhart, is ignoring the problem.

“Charleston doesn’t see it, or chooses not to. People downstate don’t understand that many of the adults in these kids’ classrooms up here aren’t actually teachers — because the teachers have gone elsewhere for better pay.”

Imagine, she said, if hospitals started hiring people with no medical background to be doctors. “Just pulling people off the street, handing them a clipboard, and saying, ‘Here, practice medicine.’ That’s what’s happening here in education.”

Barnhart said that many of her colleagues and fellow educators feel powerless at the end of the day.

“The cost of living in the panhandle is nowhere near the rest of West Virginia, but teachers, state workers — anyone whose salary is coded into law — get the same base pay. If you live elsewhere, that’s not a big deal. But if you move here, you suddenly realize this is a crisis.”

Parents, she said, are often unaware of just how bad the situation has become.

“They’ll see the bus driver shortage on the news and get outraged about routes being cut. But they don’t know what’s happening inside the classrooms. They don’t see how many positions go unfilled all year, or how often classes are just split up when a teacher calls out — overcrowding the ones that are already at their limit.”

Even for those who stay, Barnhart said, burnout is inevitable.

“You have algebra teachers covering trigonometry. English teachers covering history. Some days, they still can’t find someone to cover,” she said. “When that happens, learning just stops.”

Andrew Fincham, a health and physical education teacher at Martinsburg High School in Berkeley County, has seen the pattern repeat itself year after year.

“It’s only getting worse,” he said. “And with the population growth in the panhandle, we’re running out of room. Classrooms are overflowing, and we’re sticking kids in trailers to make it work — but the turnover rate with teachers is staggering.”

Currently, Berkeley County’s student population alone — at nearly 20,000 — exceeds the total population of 26 entire counties in West Virginia. As of the start of the current school year in August 2024, Berkeley County had nearly 200 permanent substitutes hired.

“We’re losing an alarming number of teachers every year throughout the county — whether it’s retirement or leaving for more money,” Fincham said. “And the impact on students is undeniable — all schools, all grade levels.”

Fincham doesn’t see the “revolving door” getting any better without major policy changes.

“All the nearby states — Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania — adjust salaries based on cost of living. West Virginia doesn’t. It’s easy to see where this is headed. If the state doesn’t start thinking about this in a new way, in five years, it’ll be catastrophic.”

The impact on retention, added Barnhart, can’t be overstated.

“Berkeley and Jefferson counties, especially, have become steppingstones. Teachers come here, get a few years of experience, and then leave for better pay — often nearby.”

For Barnhart, the predicament is both personal and professional. “I have kids in this school system; I see it as a parent and as an educator,” she said. “It’s frustrating because I don’t want to leave, but at some point, I might not have a choice.”

Considering almost all those choices are within 30 minutes or less, Barnhart admitted it’s hard to ignore the disparity.

“If I left for Frederick County Schools [Virginia], I’d make over $6,400 more per year,” she said. “In Washington County [Maryland], over $11,500 more. And Loudoun County [Northern Virginia], almost $25,000 more.”

The numbers don’t lie

At the end of the day, however, this isn’t a new conversation for people like Barnhart, Fincham, and thousands of others within the region. In recent decades, West Virginia’s education landscape has been punctuated by significant teacher strikes, notably in 1990 and 2018 — both primarily driven by concerns over inadequate compensation and escalating health care costs.

The 2018 strike, in particular, saw approximately 20,000 educators and school personnel shutting down schools across all 55 counties, culminating in a 5% pay raise for all state workers.

And yet, in 2025 — as in most years previous — West Virginia sits either dead last nationally or perilously close to dead last on just about any average teacher salary list you come across — jostling for position between Florida, South Dakota and Missouri year after year. Be that as it may, according to the most recent data available from the National Education Association, the estimated national average annual salary for teachers sits at $71,699 — while West Virginia shuffles in at $53,336.

That said, the Eastern Panhandle’s three core counties — Berkeley, Jefferson and Morgan — are the fastest-growing in the state, and closest to the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area, making them highly susceptible to issues like cost-of-living disparities and teacher-pay inequities.

According to the most recent data from the West Virginia Department of Education, the average annual teacher salary in Berkeley County lands at $55,412; the average for Jefferson County comes in at $54,153; and Morgan County sits at $55,624.

Compare that to West Virginia’s poorest county, McDowell, where the average teacher salary is $53,296. However, the average home value in McDowell County hovers around $35,000 — with the median home sale price standing at approximately $41,000. Accordingly, almost all cost-of-living data is lower or significantly lower in McDowell County. To that end, $53,296 goes a long way there, as it does in numerous other counties in West Virginia that boast similar cost-of-living data.

By contrast, average home values in Berkeley County climb into the $335,000-plus range. In Jefferson County, it’s even higher, with values exceeding $380,000. In Morgan County, values can exceed $350,000. The cost of living within these three counties is commensurate with those values. But the average teacher salary within the Eastern Panhandle comes in at $55,063 — not even $2,000 more annually than West Virginia’s poorest county.

Talk to anyone close to this issue, and they will tell you in no uncertain terms — it’s becoming all but impossible to work as a teacher or education service worker in the Eastern Panhandle and pay the bills. And when extra money does arrive, it’s in the form of a statewide raise — without consideration for locality pay — which keeps that allotment relatively small in proportion to the ever-widening economic gap between the Eastern Panhandle and the rest of the state.

Bargaining power

“It’s economics 101,” said John Deskins, director of West Virginia University’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research. “If salaries remain the same across the state, schools in more competitive job markets like the Eastern Panhandle will struggle to attract and retain teachers. It’s a matter of supply and demand — higher costs and a stronger labor market require higher pay.”

Berkeley County Schools Superintendent Ryan Saxe, formerly superintendent in Cabell County, echoed the sentiment — and admitted to not fully grasping the depth of the problem until taking his current job.

“In my previous county, we competed with Ohio and Kentucky for teachers, but the disparity wasn’t nearly as severe as what we see here with Maryland and Virginia,” he said.

Saxe doesn’t believe West Virginia needs to match those salaries dollar for dollar, “… but we must close the gap,” he said. “Right now, we have around 200 permanent substitute positions because we can’t fill them with certified staff. That depletes our substitute pool and leaves us constantly reposting vacancies for high-need areas.”

Sen. Patricia Rucker, R-Jefferson, believes part of the issue is Charleston’s reluctance to even acknowledge cost-of-living disparities.

“The federal government has already done the research to determine appropriate salary increases for employees based on regional economic conditions,” she said. “A similar approach for public employees in high-cost areas in our state makes sense.”

But the push for locality pay has failed repeatedly, she said, primarily due to opposition from lawmakers outside the Eastern Panhandle.

“The Senate has passed similar measures three times, only for them to fail in the House,” Rucker said, “The last time, we were 14 votes short. That’s a big gap.”

The resistance comes from a long-standing belief in uniform pay across all 55 counties, said Dale Lee, president of the West Virginia Education Association.

“But that resistance mindset ignores an economic reality,” Lee said. “A few years ago, an attempt to secure locality pay for state police was soundly defeated. The challenge is that while it would benefit a few counties, the majority wouldn’t see any advantage — so their delegates aren’t inclined to support it.”

Instead of direct locality pay, some legislators are exploring alternatives, like reducing the “local share,” which would allow high-growth counties to keep more of their tax revenue to fund education salaries.

“If that money is earmarked for salaries and benefits, it could be a real solution,” Lee said.

As Lee indicated, the shortage isn’t limited to teachers — state police, social workers and other public employees face the same problem in high-cost areas.

Former West Virginia delegate John Doyle has been advocating for locality pay for over 30 years, first proposing a housing allowance in the early 2000s as a way to soften opposition.

“The state would provide a housing allowance based on cost-of-living data,” he said. “Every county would be ranked from 1 to 55, with the median county serving as the baseline. Any county ranked above the median would receive some level of housing allowance — smaller for those just above, larger for the highest-cost counties.”

He recalled that when cost-of-living data was first released to legislators, some were stunned by the housing prices in the Eastern Panhandle. “They assumed we all lived in large homes. I had to explain that I lived in a 1,000-square-foot FHA rancher, and it was worth almost double the state average.”

Doyle also warned against the idea that raising salaries in border counties would simply cause a ripple effect of teacher migration.

“Salaries don’t need to match Maryland and Virginia — just get close enough. If the gap is $20,000, they’ll leave. If it’s $10,000 or less, they might stay.”

But the state has spent decades failing to act. Doyle pointed out that in 1990, West Virginia was ranked 26th in teacher pay after a major statewide raise under former Gov. Gaston Caperton. By the late 1990s, Maryland and Virginia had surged past it once again.

“Every few years, the issue reaches a boiling point, like the 2018 teacher strike, which resulted in a 5% statewide raise — but failed to address the Eastern Panhandle’s unique economic challenges,” he underscored.

With legislative momentum reliably sluggish, greater political action might be required, said Rucker — who also chairs the Government Organization Committee.

“If we don’t have enough qualified teachers, we are failing to meet our constitutional obligation to provide an efficient education system. A class action lawsuit could force the state’s hand,” she said.

On the economic side, Deskins sees another consequence of inaction: economic decline.

“If schools decline due to this crisis, the region becomes far less appealing. People don’t want to move to areas with struggling schools, which would ultimately slow economic growth,” Deskins said.

Essentially, explained Deskins, West Virginia’s fastest-growing region — the only part of the state successfully attracting new residents — is being left to fend for itself.

“From a broad economic-development perspective, we’re making one of the state’s most promising regions less attractive — ultimately working against ourselves,” Deskins said.

The political fight will only continue, and will hopefully play a prominent role in the current legislative session, said Doyle — who believes the Eastern Panhandle finally has strength in numbers.

“The Eastern Panhandle now has more than 10% of the legislature,” Doyle said. “That gives our delegation real bargaining power. If they unify and make this a non-negotiable priority, they can trade support on other bills to get it passed.”

Rucker agreed.

“The delegates from this region have better strength in numbers, and are working hard to educate their colleagues and emphasize that this benefits the entire state, not just the Panhandle,” she said.

Nonetheless, Lee remains skeptical.

“In my experience, when the legislature makes something a priority, they find the money for it,” he said. “If this becomes a priority, a solution will follow. But that remains to be seen.”

Doyle, however, was more blunt: “At the heart of it all is the fact that the state doesn’t want to give money to teachers because they want to be able to give a giant tax break to corporations.”

Repeated requests for comment from State Superintendent of Schools Michele Blatt went unanswered.

The cost of inaction

Imagine a moment in the near future in the Eastern Panhandle — likely Berkeley or Jefferson Counties — when a brand-new high school opens with all the pomp and circumstance that comes with such occasions. And on day one, as the doors open and the students pour through them en route to homeroom and the new year ahead, not a single certified teacher is there to greet them. Rather, every room, and every subject, is being covered by a substitute.

Sounds crazy? Many education professionals in the Eastern Panhandle are calling it something else: inevitable.

“I can easily see that happening — we’re drowning,” said Jana Woofter, a chemistry and physical science teacher at Spring Mills High School in Martinsburg. Woofter also serves as president of the Berkeley County Education Association.

“Bills are often triple what they are in other parts of the state,” she said. “Housing costs are through the roof. Berkeley County tries to help with a housing allowance, but Jefferson and Morgan counties don’t have those same benefits. Even with the assistance, my members are struggling — especially with PEIA [West Virginia’s Public Employees Insurance Agency] costs rising.”

The struggle isn’t just with the state. Clay Anders, a physical education teacher at C.W. Shipley Elementary in Jefferson County’s Harpers Ferry, is frustrated that even as property values have doubled, teachers haven’t seen a county-based raise in over a decade.

“The local levy passed again, and there’s millions in additional revenue coming in — but none of it has gone to us in quite a while,” he said. “Meanwhile, the board office has added new positions and given themselves raises every year.”

As of Nov. 6, 2024, the Jefferson County School Excess levy passed with ease — totaling $25,427,656. According to Jefferson County Schools, the bulk of the levy — $19,376,035 — will go to “salary assistance for teachers and service personnel.”

At the same time, Anders pointed out, extra-pay options that once existed for Jefferson County educators have disappeared.

“The county cut a program that allowed teachers to earn up to 3,000 extra dollars per year. That was real money that made a difference. But then they phased it down to $1,500, and now it’s gone completely.”

The level of participation in that program told him everything he needed to know.

“Nearly 98% of eligible teachers took part in it,” Anders said. “That should tell you how much we need the money.”

He believes that if the county won’t act, teachers may have to take matters into their own hands.

“Maryland and Virginia have county-based unions that fight for local pay,” Anders said. “West Virginia doesn’t. We only have state-level unions, and they aren’t fighting county battles.”

Additionally, Anders and a group of teachers are preparing a Freedom of Information Act request to uncover exactly where the money is going.

“The board claims there’s no money for teacher raises, yet they’re increasing salaries at the top. If every million dollars in new revenue could mean an $800 to $900 raise per teacher, then where is that money going?”

The answer, at least in Berkeley County, according to Board of Education member Damon Wright, is complicated.

“Most of our budget already goes to salaries,” Wright said. “And we’ve denied requests for new administrative positions to keep costs down. But we continue to have growth needs — especially when it comes to mental health services for students, which require more funding.

“That said, every time we dip into reserves, we run the risk of the state stepping in and questioning our financial management. We’ve increased the housing allowance, and we’ll keep looking for ways to supplement pay, but we can’t solve this alone.”

The challenges only get more complex, he said, when Charleston refuses to act.

“The state doesn’t believe in cost-of-living adjustments. They think if we raise salaries in high-cost areas like the panhandle, teachers from rural counties will flood the region. But that’s not realistic. Most teachers in McDowell and similar counties are among the highest-paid professionals in their communities. Here, teachers need roommates just to afford rent.”

Michelle Pereschuk, a special education teacher at South Middle School, called the system broken and confessed that teachers are running out of reasons to stay — including herself.

“I’ve been at the tipping point for years,” she said. “I was born and raised in Berkeley County. My kids are in the school system. I want to stay — but I can’t afford it much longer.”

Like many in the county, Pereschuk’s mortgage swallows her paycheck. She once considered a position in nearby Washington County, Maryland, that would have paid her $11,000 more in the first year and up to $17,000 more over time. She ultimately stayed due to personal reasons, but the pull to leave grows stronger every day.

“Winchester City Schools and Frederick County, [both in Virginia], are 20 minutes from my house. Maryland and Virginia also allow out-of-state teachers to send their kids to school there. For the first three years, you pay a small tuition fee, then your kids attend for free. If I move, I could take my youngest with me and give him a better-funded education while making a lot more money.”

Such decisions aren’t just being measured in Pereschuk’s household, she assured, but rather, in many homes across the region.

“Off the top of my head, I can name at least 10 people in my school alone who are seriously considering leaving,” she said.

Woofter, who works multiple jobs to make ends meet, added that, even for those who choose to stay, survival requires sacrifices.

“I run the science fair for my school and the county, coordinate academic competitions, tutor, sell tickets at events — anything to make extra money. If I moved across the border, I wouldn’t have to do all that. But I stay because I love it here.”

As for rising insurance costs, Wright said, whatever raises the state offers at this point are quickly wiped out by PEIA increases.

“The misconception is that a raise actually means more money,” he said. “It doesn’t. When insurance premiums jump 40%, and co-pays triple, as they’re set to do, it’s actually a pay cut. Later this summer, when those PEIA increases hit, I think we’ll see a mass exodus — not just teachers, but public employees across the board.”

Without action, warned Woofter, the situation will only deteriorate. She’s already seeing it play out at her own school.

“Spring Mills High School opened in 2013. In just over a decade, fewer than 20 original staff members remain. That kind of turnover is devastating.”

Moreover, Wright said, Charleston’s inaction is feeding into another, larger movement — the privatization of education.

“Rather than addressing the crisis in public schools, the state is using the decline as an excuse to push private schools, charter schools and voucher programs,” he said. “The problem is, 25% of Berkeley County’s students have special needs, and public schools are required to serve them — private schools are not.”

West Virginia doesn’t fully fund those services so counties cover the gap.

“If lawmakers shift funding away from public schools to private options, that burden grows,” Wright said. “They’re letting the system fail so they can justify alternatives.”

At the end of the day, he said the community is the last line of defense.

“We’re already in crisis mode — whether the state chooses to address it or not. The public needs to understand just how bad this is getting. And the only way any of this changes is if the public demands it — loudly. If people in the panhandle make enough noise, Charleston can’t ignore it forever.”

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

West Virginia Watch is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. West Virginia Watch maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Leann Ray for questions: info@westvirginiawatch.com.

The post ‘We’re drowning’: Teacher pay vs. cost of living approaches crisis level in WV’s Eastern Panhandle appeared first on westvirginiawatch.com

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed

Ohio neighborhood fears landslide as retaining wall slips

SUMMARY: In Portsmouth, Ohio, a retaining wall has been slipping for about five years, causing fear among residents like the Yuri family who moved in just before the slip began. Despite support beams installed two years ago, cracks in the wall allow water to gush through, flooding parts of the road and raising concerns about a potential catastrophic landslide. Local councilman Shawn Dun highlights questions about the wall’s stability and estimates repair costs near $2 million, with the city seeking grants to fund the work. Residents anxiously await repairs, hoping the problem will be resolved soon to prevent disaster.

A cloud of concern hovers over one Portsmouth neighborhood. Those living along Richardson Road wonder how much longer a retaining wall will hold and keep a hillside from sliding that would damage their property. The support wall began slipping 5 years ago. A couple years later, support beams were put in place for a problem that those living along the street say is a ticking time bomb.

FULL STORY: https://wchstv.com/news/local/a-ticking-time-bomb-has-a-portsmouth-neighborhood-living-in-fear

_________________________________________

For the latest local and national news, visit our website: https://wchstv.com/

Sign up for our newsletter: https://wchstv.com/sign-up

Follow WCHS-TV on social media:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/eyewitnessnewscharleston/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/wchs8fox11

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/wchs8fox11/

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed

Christian's Latest Forecast: More Dry Days; Rain Potential Late Next Week

SUMMARY: Storm Watch meteorologist Christian Boler reports mild, mostly dry weather continuing through the weekend with temperatures around 80°F and partly cloudy skies. A high-pressure system will maintain these warm, dry conditions into early next week. Some unorganized tropical rainstorms may bring isolated showers from Tuesday night into Wednesday morning, followed by a dry midweek. Saturday promises significant rainfall, helping to relieve recent dry and minor drought conditions affecting vegetation. Temperatures have shifted from below to above average this week but will dip below average later in the month. Overall, expect more dry days with rain potential late next week, improving moisture levels regionally.

FOLLOW US ON FACEBOOK AND TWITTER: https://facebook.com/WOAYNewsWatch https://twitter.com/WOAYNewsWatch.

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed

Road-widening project gets completion date, property issues remain unclear

SUMMARY: The Cross Lanes road-widening project, expanding Route 622 from Golf Mountain Road to Route 62 near Andrew Jackson Middle School, has resumed after a ten-month pause. Originally set for completion in June 2025, the new completion date is February 2027 due to delays caused by utility pole relocations. Construction is causing traffic congestion, especially around the Kroger turning light, which is being studied for timing adjustments. Despite frustrations, officials emphasize the long-term benefits. Property issues, including damage claims and easements, remain unresolved. Kanawha County lawmakers continue to provide updates as the project progresses.

Source

-

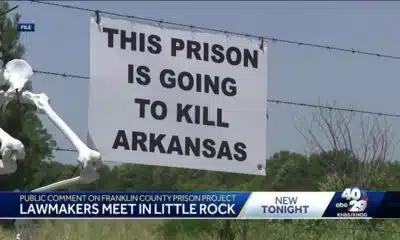

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

Group in lawsuit say Franklin county prison land was bought before it was inspected

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days ago

Lexington man accused of carjacking, firing gun during police chase faces federal firearm charge

-

Mississippi News Video7 days ago

2025 Mississippi Book Festival announces sponsorship

-

The Center Square6 days ago

California mother says daughter killed herself after being transitioned by school | California

-

Mississippi News Video7 days ago

Carly Gregg convicted of all charges

-

Local News5 days ago

US stocks inch to more records as inflation slows and Oracle soars

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

Arkansas medical marijuana sales on pace for record year

-

The Center Square7 days ago

FEMA employees fired for using government systems to engage in sexually explicit behavior | National