Mississippi Today

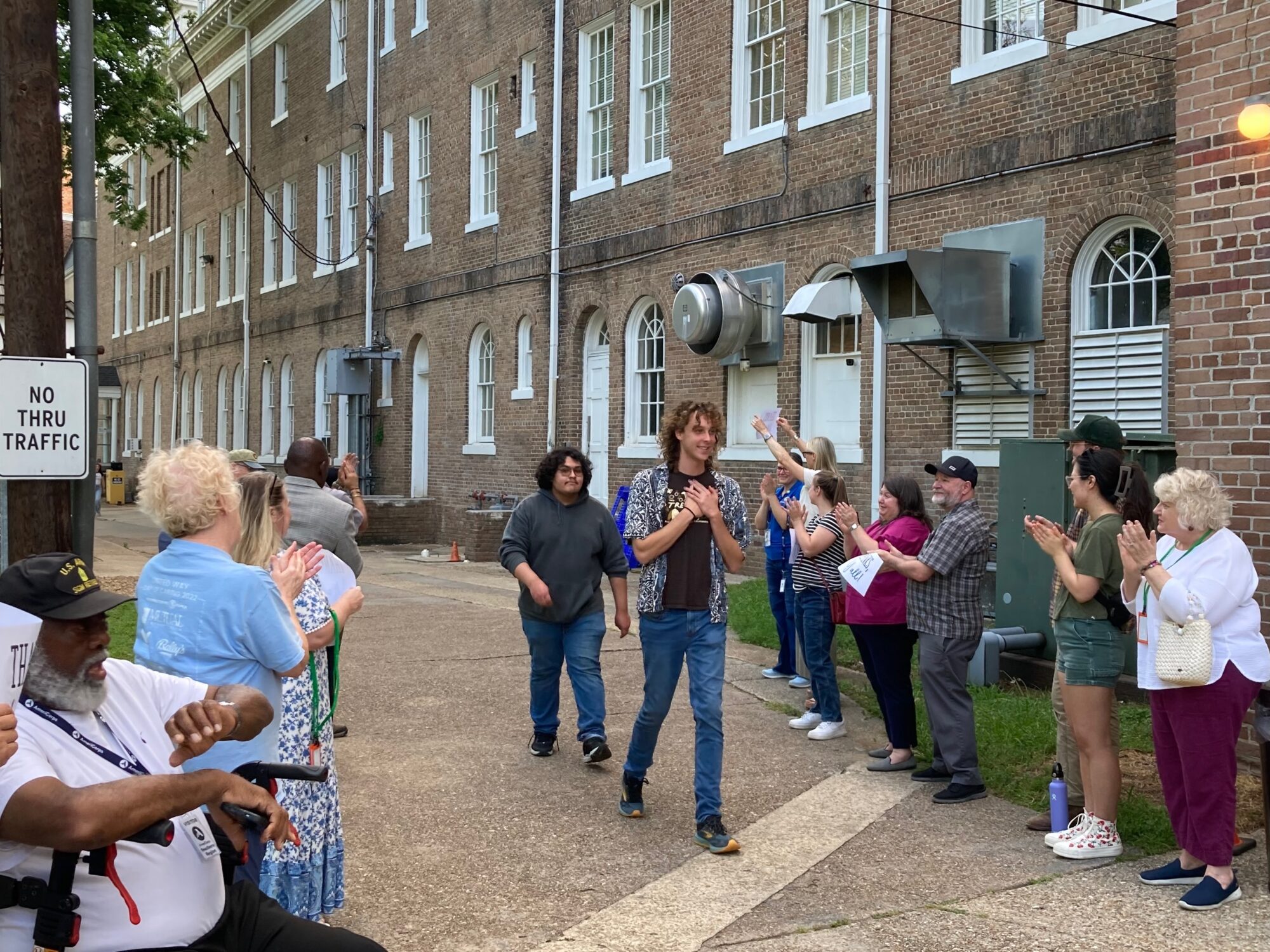

Vicksburg musters feast, gratitude for fired AmeriCorps members

April 23, 1963

William Lewis Moore, a postal worker from Baltimore, decided to march from Chattanooga to Mississippi’s capital during his one-person march against segregation, wearing a sandwich board that read, “Equal Rights for All” and “Mississippi Or Bust.”

Instead, a Klansman gunned him down in Attala, Alabama, shooting him twice in the head with a .22 rifle. The Klansman believed to have killed him went unpunished.

Moore, who was raised in Mississippi, had planned to deliver a letter to Mississippi Gov. Ross Barnett that read, “Do not go down in infamy as one who fought the democracy for all which you have not the power to prevent. … The white man cannot be truly free himself until all men have their rights. Each is dependent upon the other.”

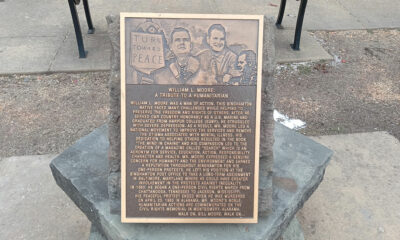

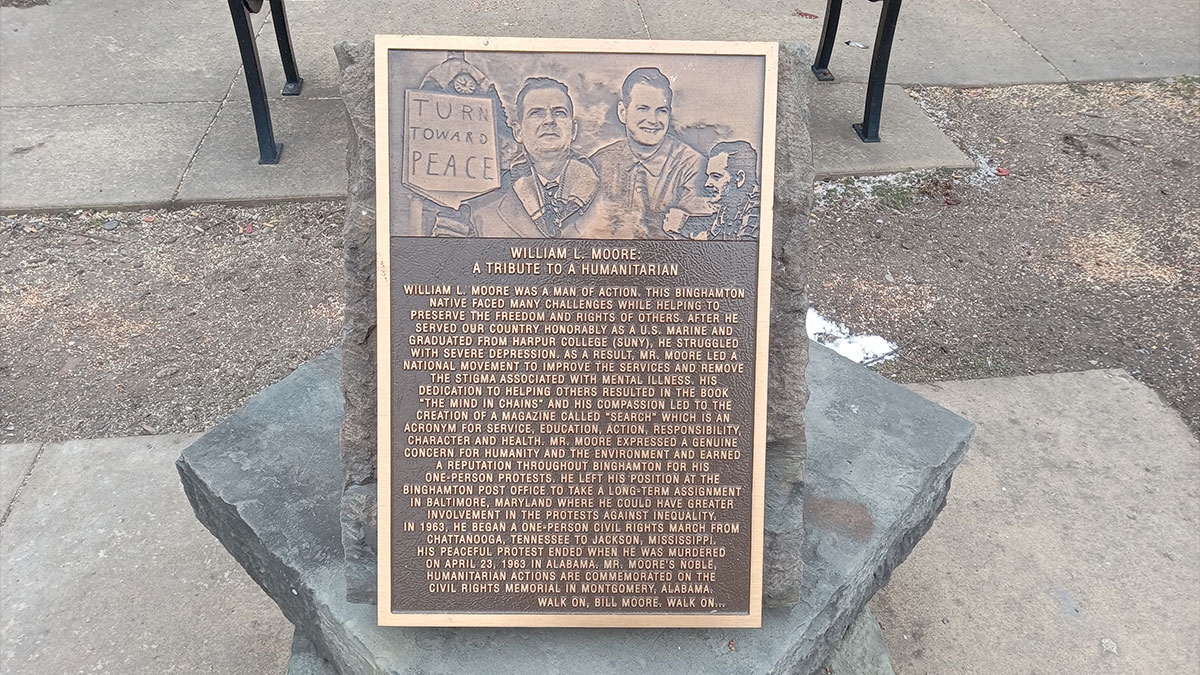

Folk singer Phil Ochs wrote a song about Moore, among the 40 martyrs listed on the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama. In 2003, Mary Stanton wrote a book on Moore’s journey, “Freedom Walk: Mississippi or Burst.” Seven years later, his hometown in Binghamton, New York, built a plaque to honor him. In 2019, a historic marker was unveiled at the sight of Moore’s slaying.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1963, William Moore killed on anti-segregation march

April 23, 1963

William Lewis Moore, a postal worker from Baltimore, decided to march from Chattanooga to Mississippi’s capital during his one-person march against segregation, wearing a sandwich board that read, “Equal Rights for All” and “Mississippi Or Bust.”

Instead, a Klansman gunned him down in Attala, Alabama, shooting him twice in the head with a .22 rifle. The Klansman believed to have killed him went unpunished.

Moore, who was raised in Mississippi, had planned to deliver a letter to Mississippi Gov. Ross Barnett that read, “Do not go down in infamy as one who fought the democracy for all which you have not the power to prevent. … The white man cannot be truly free himself until all men have their rights. Each is dependent upon the other.”

Folk singer Phil Ochs wrote a song about Moore, among the 40 martyrs listed on the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama. In 2003, Mary Stanton wrote a book on Moore’s journey, “Freedom Walk: Mississippi or Burst.” Seven years later, his hometown in Binghamton, New York, built a plaque to honor him. In 2019, a historic marker was unveiled at the sight of Moore’s slaying.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Amid crackdown on universities, Millsaps prof’s job in flux

Amid a national maelstrom of attacks on academic freedom, the fate of James Bowley, the former chair and professor of Religious Studies at Millsaps College, hinges on a 10-word email he sent to his class of three students the morning after the presidential election. Nearly a month after a grievance committee repudiated his subsequent termination over those 10 words, his status remains in flux.

The day following his email, Bowley found out that he had been placed on paid administrative leave pending a review of his use of a Millsaps email account “to share personal opinions” with his students.

Around the days of the election, racist messages targeting African American students had been sent using the anonymous campus messaging platform Yik Yak. The FBI had informed the Millsaps community via email that it, along with law enforcement and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, was investigating those messages.

“I personally would not send that kind of content to my class. But I understand the disappointment behind the email, understand the human sympathy, especially what happened with the Yik Yak post,” said David Wood, chair of the Modern Languages department at Millsaps College, referring to racist and threatening messages directed at African American students on the anonymous messaging platform Yik Yak, around the days of the 2024 presidential election.

“I knew the students were fearful. So I canceled my class,” Bowley said. “And I do not regret that for a second.” His 10-word email explained why the class was being cancelled: “to mourn and process this racist fascist country.”

Bowley filed a grievance against his leave of absence with the university’s grievance committee, which could not identify any specific policy that he had violated. It recommended in December that Bowley be reinstated immediately; that the Interim provost issue a formal apology to him, and that he be compensated for a loss of income that arose from his removal from a study abroad course he was supposed to have taught.

Weeks later, Bowley’s employment was terminated, by the interim provost — a decision he appealed. The interim provost at the time, Stephanie Rolph, was a candidate for the full-time position.

Now, nearly a month after the grievance committee decided to allow the terms of Bowley’s reinstatement be negotiated, his employment remains in flux as he waits for Millsaps’ president to affirm or overrule their decision.

The purpose of the college’s action “is to demonstrate the power of the administration over the faculty,” Bowley said. “I think the whole point is to make faculty self censor.”

The termination of Bowley comes amid a nationwide crackdown by universities and the Trump administration on speech by students and faculty. Since 2023, dozens of faculty members have been disciplined, or even fired. Since March, more than 1,500 international students have seen their visas revoked, with some even being detained without due process. And top universities have seen threats of funding freezes if they do not agree to laundry lists of demands and restrictions.

On Monday, Harvard University, which has vowed not to “surrender its independence or constitutional rights,” sued the Trump administration in an attempt to block them from freezing $2.2 billion in federal funding and an additional $1 billion in grants, which the administration in a letter had said it would do if the university did not overhaul its admissions and hiring policies, among others, allow for federal oversight of its operations, and commission external audits of a number of departments.

This letter, which the Trump administration now says was sent in error, came about a month after Columbia University capitulated to similar demands by the administration – in its case, which included empowering campus security to make arrests, suspending students involved in protests last spring, and placing its department of Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies under administrative receivership.

On Tuesday, the American Association of Colleges and Universities, which has more than 800 member institutions, issued a public statement, condemning “undue government intrusion in the lives of those who learn, live, and work on our campuses” and “coercive use of public research funding.”

Nearly 200 leaders of educational institutions signed the statement, including Millsaps College – the only Mississippi institution to do so. The president of Columbia University did not.

“Millsaps promises free speech to its faculty members and when it makes a promise like that it should stand by that promise and protect it,” said Haley Gluhanich, senior program counsel of FIRE, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education. In Bowley’s case, she said, “We saw these violations of fundamental due process rights – the fact that he was put on administrative leave before he even had a hearing.”

Millsaps’ Faculty Handbook says a faculty member is “entitled to freedom in the classroom in discussing the subject matter of the course, but should be careful not to introduce controversial matter which has no relation to the subject.” It elaborates that “when speaking or writing as a citizen, the teacher is free from institutional censorship or discipline, but this special position in the community imposes special obligations,” because the public may interpret the words of a faculty member as being representative of the position of the institution.

However, in the grievance committee’s December recommendation, it found that the handbook “does not offer guidance on how to distinguish personnel matters from matters of academic freedom,” and that this lack of clarity appeared to expose tenured faculty members to a disciplinary process that was subject to the sole decision of any acting provost, with no recourse.

“When they are sharing a personal opinion, a criticism of an election,” said Gluhanich, “no reasonable person is going to assume that that is the speech of the college.”

“Millsaps truly shaped me. It broke down the conceptions that I had of the world and religion and philosophy and ideas. By doing so it forced me to build them back up,” said Elizabeth Land, an alumna of Millsaps College. “I was taught to think for myself. And that’s a gift that you can’t put a price tag on.”

Land circulated a petition last December calling for Bowley’s reinstatement – a decision that in April, has yet to be made.

Joey Lee, director of communications at Millsaps College said, on behalf of the office of the president, that they could not comment on ongoing personnel issues.

“If I win,” Bowley said, “It is a win for students and for faculty and for academic freedom.”

Michael Guidry is an alumnus of Millsaps College, having attended from 2001 to 2005

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

My grandfather’s law firm just bowed to Trump. It goes against his and America’s values.

Editor’s note: Nina Rifkind is an adjunct professor at the University of Mississippi Law School and the granddaughter of one of the founders of a major national law firm that recently settled a dispute with President Donald Trump. She agreed to write about that settlement and about her grandfather’s story for Mississippi Today Ideas.

Last month, the Trump administration issued an executive order aimed at the New York law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton and Garrison (known to many as just “Paul, Weiss”).

The order threatened the firm with withdrawal of the security clearances required to do certain legal work as retribution for work Mark Pomerantz, a former Paul, Weiss partner, had done while employed by the Manhattan District Attorney’s office in connection with the investigation of Trump’s businesses. Within days, Paul, Weiss announced that it had struck a deal with the Trump administration, offering, among other things, millions of dollars’ worth of free legal work for administration endorsed causes, and changes in hiring practices in exchange for the dismissal of the executive order.

While I had been angry about many of the acts of this administration that seemed to undermine the very institutions and ideals of American government and society that I had been raised to revere, this one struck particularly close to my heart.

On the one hand, I had no particular interest in the affairs of this law firm, located half a continent away from my home in Mississippi, and to which I had no personal connection except that it was where my grandfather, Simon H. Rifkind, had practiced law until his death at the age of 94 in 1995. On the other hand, it seemed to me that the executive orders addressed to this law firm, and, ultimately, a handful of others, were an assault on my chosen profession, on our legal system and on our democracy as a whole.

So when the chairman of the firm Brad Karp, in defense of the decision to make a deal, cited the firm’s “Statement of Firm Principles,” written by my grandfather in 1963, I contacted my sister, Amy Rifkind, a lawyer practicing in Washington, D.C. We quickly decided to speak out. We did so in the form of a letter to Mr. Karp, explaining that his decision was an affront to those very principles he claimed to defend.

In that letter, we wrote that our grandfather believed that to practice law in this country is a privilege that comes with “responsibilities both to our profession and our country” and a duty “to protect ‘the prizes of our civilization.’” In light of those duties, we noted that, “We are confident that neither our grandfather, nor his colleagues with whom he built Paul, Weiss, would have negotiated a truce for themselves when the rest of the legal profession remains under threat for doing its jobs as lawyers. Consistent with his values, he would have above all sought to protect the independence of the bar, not just the firm.”

READ MORE: The full letter the Rifkind sisters wrote to Brad Karp

In writing the letter, we hoped that our small evocation of our grandfather’s enduring values would inspire others to speak out with their own messages of hope and courage in the face of adversity. We have been simultaneously stunned, humbled and honored by the media outlets (including Mississippi Today) and individuals that have chosen to amplify our message.

My grandfather was born in Russia at the turn of the last century. He often said that he was born and lived in the 16th century until, at the age of 9, he left his little village and immigrated with his mother and sisters to the United States. Before he left, he had never seen a power-driven piece of machinery, experienced running water or worn any factory-made garment. As is the case with many immigrants, he arrived in this country with no ability to speak English, but with a determination to make a home here. And also like many immigrants, by his teens, that determination had developed into a deep sense of patriotism. That love of country continued to develop throughout his life, fueled by his own varied personal and professional experiences.

He served the public in a variety of ways. He served as a legislative aide to Sen. Robert Wagner, helping to draft some of the New Deal legislation that helped stem the effects of the Great Depression. In 1945-46, as an advisor to Generals Eisenhower and McNarney in Europe, he brought to light the horror and despair experienced by hundreds of thousands of residents of the displaced persons camps in the wake of the Nazi genocide. He spent a decade as a federal judge in the Southern District of New York and a year as special master for a multi-state dispute over use of the Colorado River. But even in private practice at Paul, Weiss, where he spent most of his career and where many of his clients were large private corporations, he believed his work should, and did, serve the public good.

We all know that lawyers get a bad rap as they are often described as greedy and predatory. But to hear my grandfather talk about the practice of law, as my sister and I did during our family’s regular Sunday afternoon visits to his apartment throughout our childhood, you would think he was part of the noblest profession in the world. As a fierce defender of our adversarial system, he believed everyone deserved vigorous and ethical counsel, no matter how rich or poor, popular or unpopular. He believed that every client, whether paying top dollar or receiving the benefit of pro bono representation, deserved the highest quality of work his or her lawyer could provide.

And he believed, as he wrote at the end of his life, that “lawyers are licensed beneficiaries of privileges and immunities received as gifts from the community in which they practice and that they hold these gifts in trust for the service of the community.” In other words, all lawyers, regardless of the nature of their practice, who take their roles seriously and perform their duties with skill and integrity, provide a benefit to society.

My grandfather’s life spanned nearly the entirety of the 20th Century — a century that, despite some very dark moments, saw our country lead the charge in achieving the greatest advances in freedom and prosperity in human history. And while he benefited from those advances, he never lost sight of the fact that the foundations of that freedom, equality and prosperity are fragile and dependent on the individual and institutional pillars of our American democracy.

Indeed, in 1954, he wrote: “Every American generation has inherited from its predecessor the memory of freedom, of liberty and of constitutional government; but every generation if it would retain these prizes of our civilization, must reacquire them in its own lifetime. This day when the winds are full of doctrines subversive of the Constitution, inimical to our liberties, is the time to redevelop muscle and determination to defend them. In their defense we shall survive.”

In the most important respects, my family is not unusual. These principles and values were passed down through casual interactions, a commitment to religious and secular traditions and through modeled behavior. We laughed when my grandfather’s views seemed out of touch with the times. And we used his values as a blueprint to form our own paths and priorities.

I assume most of us grew up with at least some influential figures who adhered to and communicated a set of core values, whether explicitly or by example. And I suspect that despite our different backgrounds and experiences, if we examine those values closely, we will find that there is more that unifies us than divides us.

My sister and I wrote the letter to Mr. Karp as a reminder of what Paul, Weiss’s stated “principles” really mean for the legal profession and for American democracy. In doing so, we revisited those core beliefs ourselves, and hopefully inspired others to as well.

Perhaps, with such values in mind, we can rise above the destructive forces of greed, cynicism and selfish grievance, remember that together we are more than the sum of our parts, and continue our collective march toward freedom, equality and prosperity.

Nina Rifkind is a graduate of Yale College and New York University School of Law. Following law school, she practiced law first in New York and later in Los Angeles. Since moving to Oxford, she has continued to practice in a variety of capacities, most recently as an independent contract attorney and is an adjunct professor at the University of Mississippi Law School, where she teaches the Law and Religion course. She has taught legal writing at the USC Gould School of Law and Advanced Legal Writing at the University of Mississippi. She currently serves on the boards of the Jewish Federation of Oxford and the Oxford School District Foundation.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed5 days agoArkansan appears on Wheel of Fortune

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed6 days agoDrivers brace for upcoming I-70 construction, slowdowns

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed3 days agoJim talks with Rep. Robert Andrade about his investigation into the Hope Florida Foundation

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days agoThursday April 17, 2025 TIMELINE: Severe storms Friday

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

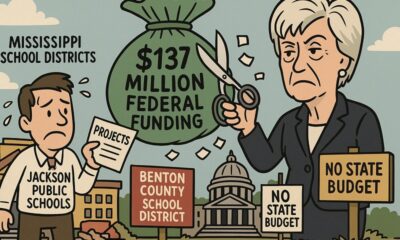

Mississippi Today6 days agoSee how much your Mississippi school district stands to lose in Trump’s federal funding freeze

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days agoCruz, Zeldin: Roll back Biden-era regulations targeting oil and gas industry | National

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoDeSantis blasts House on its potential cuts to law enforcement budgets | Florida

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoOp-Ed: Colleges shouldn’t need remedial algebra classes: Five K-8 policy solutions to address math proficiency | Maryland