Mississippi Today

Two years after funds were obligated to bring high-speed internet to more than 4,000 homes in rural northeast Madison County, zero have been served

Kadiyah Nunn was one of several employees sent to work from home by her job’s management in 2019 when COVID-19 hit Mississippi.

Dependent on her satellite service for an internet connection at her home in rural Sharon in Madison County, Nunn experienced slow internet and static calls to customers, resulting in repeated questions and statements.

After being given two weeks without pay by her employer to look for another internet service, Nunn had no luck. She was let go.

Nunn went eight months without a job and almost had her car repossessed over something she said she “had no absolute control over.”

“It was the most horrific day of my life to lose a good job,” Nunn told Mississippi Today, “not because I did anything wrong – or wasn’t completing my tasks – but because of the internet.”

Two years ago, the Madison County Board of Supervisors approved funding for over 370 miles of high speed internet to cover more than 4,000 homes in the rural northeast areas of Madison County in District 5 – carried out in collaboration with Comcast.

These areas include Camden, Sharon, Pine Grove and some parts of Canton.

As of Aug. 17, zero areas have been covered within this newly estimated $17 million project, said District 5 Supervisor Paul Griffin, president of the Madison County Board of Supervisors.

The original $22 million cost was lowered a month ago after Comcast conducted a walkthrough of where fiber would be installed.

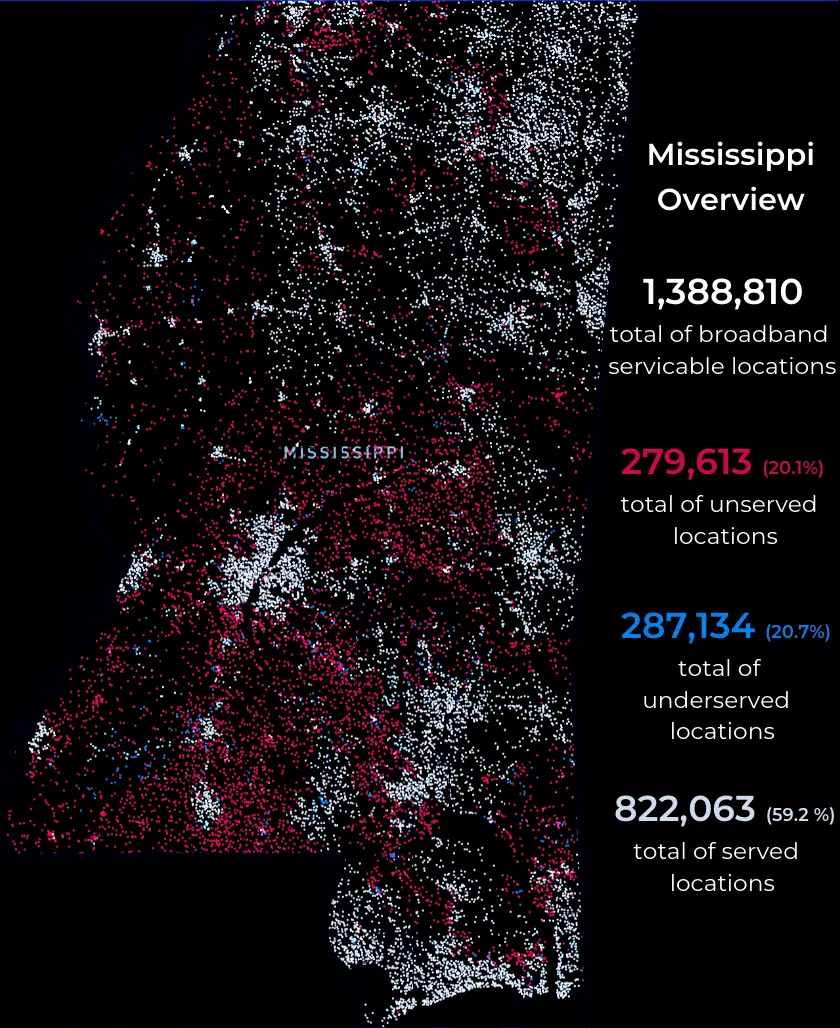

Federal officials have been pouring billions of dollars into the expansion of high-speed internet in Mississippi, yet the tedious process of selecting providers and distributing funds has resulted in a slow rollout.

After receiving no actions and few answers from county officials, residents in the rural northeast portions of Madison County are left wondering when broadband will come to their area.

Griffin said “red tape” – actions the government requires to perform services – have delayed the project’s progress.

“It is not Madison County. It’s been the federal government getting the money down to the local government,” Griffin told Mississippi Today. “The district is waiting on the funds that have gone through the government down to the state, to move from the state down to internet providers.”

Madison County, which received over $20 million in American Rescue Plan Act funds, set aside $10 million for the project but now is contributing half of that. The county applied for a Capital Project Fund aid match through the Broadband Expansion and Accessibility of Mississippi office.

If the county receives the grant, Comcast will also contribute funds up to $7 million to cover the remaining balance, the Board of Supervisors said.

With only partial funds in hand, the project remains at a standstill.

In Madison County, a little over a fifth of the locations in the county are eligible for funding, according to the Mississippi’s broadband office. Of those locations, 73% are unserved areas.

And of the areas unserved, at least half are in the rural northern areas that Griffin said are to be prioritized.

As this delay continues, many of Madison County’s schoolchildren and adults, particularly in the least wealthy parts of the county, can’t access high-speed internet. Griffin’s advice is to just keep holding on.

“There was no future to get the internet at all until two years ago when federal funding started coming down,” Griffin told Mississippi Today. “We’ve held on that long. Hopefully we can hold on for another year.”

In Sharon, nearly all – over 94% – of locations are considered unserved and underserved, according to data collected in 2022.

When it was announced broadband high-speed internet was coming to Nunn’s area, she said she believed the community was progressing and the Board of Supervisors cared about its citizens. But with the prolonged wait, the mother of three says it’s becoming difficult to raise her family in the area she loves and grew up in.

“This is my livelihood. This is how I provide for my family,” Nunn said. “The world is technology now. You need the internet to basically do anything.”

In rural areas like Nunn’s without cable, fiber, or DSL internet access, the commonly served satellite internet providers are Viasat and HughesNet. Satellite internet is the only thing she’s able to get, but these services are not recommended for those who work from home and need high-speed connection.

The 24-year-old said she has satellite internet service with Viasat, but the 100 GB plan package she needs runs $275.45 per month, which is higher than the average cost of satellite service ($100). Nunn said the 100 GB wouldn’t even last her two days before it’s used up and begins to run slow.

“This is becoming too much. People in the Canton area mention to me that I can get Xfinity Internet that’s priced at $10 or $13 per month because I have low income and children,” Nunn continued. “I go to check. But the providers, of course, say that they don’t operate in my area.”

Mapping remains spotty during the process of expanding broadband for residents, especially those in rural communities.

Sally Doty, director of the Broadband Expansion and Accessibility of Mississippi office, said her office is working to develop a new map to be released within the next month or two that will provide an accurate representation of broadband availability across the state.

This map will be funded by the Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment program through Doty’s office out of the $1.2 billion Mississippi will receive to serve approximately 300,000 unserved and 200,000 underserved locations across the state.

Doty said this new map will help the office accurately determine where funding should be allocated and what areas still need to be addressed. It will also help residents determine what services are available to them.

“We are really kind of turning to a new way of keeping up with who has what service in some areas,” Doty continued. “As we do with all of the grants from our office and any grant that we give out, we are going to know the exact location and the addresses where (the awardee) is going to provide service.”

The broadband deployment program will begin its application process after money from the Coronavirus Capital Projects Fund has been dispersed.

A few hours before the application for those funds closed Aug. 17, there were 103 applications and over 100 applications in progress. Of the $356.4 million that providers are asking from Doty’s office, only $162 million will be dispersed.

As more funding is distributed, Doty said the number of unserved and underserved residents will continue to shift.

“We have 268,000 unserved, but I’m not quite sure how many we will serve with this (coronavirus fund) … We hope about 35,000 or more. Then, we’re down to 233,000 unserved, so that gives us more for the underserved,” Doty told Mississippi Today. “It’s a moving target all the time.”

Cynthia Johnson, a Sharon native for over 60 years, saw firsthand the importance of access to high-speed internet for children in rural areas before and after the pandemic.

Johnson has two children, ages 15 and 16, who are required to do virtual learning and submit assignments online. But with no access to high-speed internet at home, the children have missed deadlines to turn homework in by 11:59 p.m.

Johnson said she had to call the school several times to explain their situation and plead for understanding to be granted to her children.

She said she hoped to never experience hurdles like this again and to provide her children with the same educational opportunities as the rest of the county. But because the situation has persisted for so long, she is starting to feel forgotten.

“Everything is prospering and growing around us, except for our area,” Johnson told Mississippi Today. “It makes you feel like you’re in a foreign country.”

People in the community like Johnson also see benefits of working from home, considering the lack of opening positions in the area.

“There are no jobs in Sharon. The closest thing to me would be Canton, but with gas prices, you can’t get very far” Johnson said. “If you have to go 30 miles to at least get a minimum wage, then that’s not benefiting anyone.”

According to Census Bureau data, the average commute time to work in Sharon was 52.5 minutes compared to the state’s average commute time of 25.2 minutes.

Johnson said she doesn’t know how people are supposed to manage with so little resources that help the community to grow economically and socially.

“We have always got the short end of everything out here.” Johnson stated.

MediaJustice, a national grassroots movement aimed at improving communication rights, access, and power for diverse and marginalized communities, seeks to bridge the digital divide – the gap between who benefits from reliable internet connections and who doesn’t.

In early August, the California-based organization submitted a report to Mississippi’s broadband office integrating the stories and recommendations of residents and community leaders in Utica, pushing for internet access and a visit from officials.

“How can (officials) have any sense of what kind of solutions a community wants, if they haven’t even come and told the community about what kind of solutions are possible?” Brandon Forester, the national organizer for internet rights at MediaJustice, told Mississippi Today.

Forester works to help communities see that they can have a role, have agency and make decisions about the technology in their community. Forester said he relied on the power of storytelling to detail the barriers and solutions to broadband access as identified by the experiences of residents of Utica.

“The report was to say these people exist. They’re 45 minutes down the road from the Capitol. These people are completely disconnected,” Forester continued. “And the state doesn’t even realize it.”

Utica, a rural town in Hinds County of around 600 residents, found itself grappling with similar problems as those in rural Sharon: lack of internet access and high internet rates.

Forester said some residents reported not receiving the service they paid for and others required different levels of service needs. Forester said ultimately, a common theme was that the internet was too expensive.

“Part of that is because companies essentially are monopolies. AT&T and HughesNet are not competing for the same customers, so providers are able to put whatever pricing they want on these folks,” Forester said, referring to studies conducted by the Los Angeles Times and The Markup.

In rural communities, assistance can be slow due to multiple factors, but one reason is that internet providers need incentives.

Forester said for large, publicly traded corporations, their incentives may be to maximize profits for shareholders. For Electric Co-Ops – private, nonprofit companies delivering electricity to customers –, their goal may be to connect as many people as possible.

Forester said he thinks about people’s abilities to have telehealth savings, access to education and entertainment, if only rural communities had high-speed internet.

“(MediaJustice) is trying to help people figure out how to organize their resources because it may not be that the right internet solution for one area is the same as it is for another neighborhood,” Forester explained. “It’s not about us saying this is the best thing for someone, but it’s about a community being able to make choices regarding how technology shows up for them.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=281532

Crooked Letter Sports Podcast

Podcast: The Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame Class of ’25

The MSHOF will induct eight new members on Aug 2. Rick Cleveland has covered them all and he and son Tyler talk about what makes them all special.

Stream all episodes here.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Podcast: The Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame Class of '25 appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Mississippi Today

‘You’re not going to be able to do that anymore’: Jackson police chief visits food kitchen to discuss new public sleeping, panhandling laws

Diners turned watchful eyes to the stage as Jackson Police Chief Joseph Wade took to the podium. He visited Stewpot Community Services during its daily free lunch hour Thursday to discuss new state laws, which took effect two days earlier, targeting Mississippians experiencing homelessness.

“I understand that you are going through some hard times right now. That’s why I’m here,” Wade said to the crowd. “I felt it was important to come out here and speak with you directly.”

Wade laid out the three bills that passed earlier this year: House Bill 1197, the “Safe Solicitation Act,” HB 1200, the “Real Property Owners Protection Act” and HB 1203, a bill that prohibits camping on public property.

“Sleeping and laying in public places, you’re not going to be able to do that anymore,” he said. “There’s a law that has been passed that you can’t just set up encampments on public or private properties where it’s a public nuisance, it’s a problem.”

The “Real Property Owners Protection Act,” authored by Rep. Brent Powell, R-Brandon, is a bill that expedites the process of removing squatters. The “Safe Solicitation Act,” authored by Rep. Shanda Yates, I-Jackson, requires a permit for panhandling and allows people to be charged with a misdemeanor if they violate this law. The offense is punishable by a fine not to exceed $300 and an offender could face up to six months in jail. Wade said he’s currently working with his legal department to determine the best strategy for creating and issuing permits.

“We’re going to navigate these legal challenges, get some interpretations, not only from our legal department, but the Attorney General’s office to ensure that we are doing it legally and lawfully, because I understand that these are citizens,” he said. “I understand that they deserve to be treated with respect, and I understand that we are going to do this without violating their constitutional rights.”

Wade said the Jackson Police Department is steadily fielding reports of squatters in abandoned properties and the law change gives officers new power to remove them more quickly. The added challenge? Figuring out what to do with a person’s belongings.

“These people are carrying around what they own, but we are not a repository for all of their stuff,” he said. “So, when we make that arrest, we’ve got to have a strategic plan as to what we do with their stuff.”

Wade said there needs to be a deeper conversation around the issues that lead someone to becoming homeless.

“A lot of people that we’re running across that are homeless are also suffering from medical conditions, mental health issues, and they’re also suffering from drug addiction and substance abuse. We’ve got to have a strategic approach, but we also can’t log jam our jail down in Raymond,” Wade said.

He estimates that more than 800 people are currently incarcerated at the Raymond Detention Center, and any increase could strain the system as the laws continue to be enforced.

“I think there’s layers that we have to work through, there’s hurdles that we are going to overcome, but we’ve got to make sure that we do it and make sure that my team and JPD is consistent in how we enforce these laws,” Wade said.

Diners applauded Wade after he spoke, in between bites of fried chicken, salad, corn and 4th of July-themed packaged cakes. Wade offered to answer questions, but no one asked any.

Rev. Jill Buckley, executive director of Stewpot, said that the legislation is a good tool to address issues around homelessness and community needs. She doesn’t want to see people who are homeless be criminalized, but she also wants communities to be safe.

“I support people’s right to self determine, and we can’t impose our choices on other people, but there are some cases in which that impinges on community safety, and so to the extent that anyone who is camping or panhandling or squatting and is a danger to themselves and others, of course, I fully support that kind of law. I don’t support homelessness being criminalized as such,” Buckley said.

Many of the people Wade addressed while they ate Thursday said they have housing, don’t panhandle, and shouldn’t be directly impacted by the legislation. But Marcus Willis, 42, said it would make more sense if elected officials wanted to combat the negative impacts of homelessness that they help more people secure employment.

“There ain’t enough jobs,” said Willis, who was having lunch with his girlfriend Amber Ivy.

The two live in an apartment together nearby on Capitol Street, where Ivy landed after her mother, whom Ivy had been living with, suffered a stroke and lost the property. Similarly, Willis started coming to eat at Stewpot after his grandmother, whose house he used to visit for lunch, passed away.

Willis holds odd jobs – cutting grass, home and auto repair – so the income is inconsistent, and every opportunity for stable employment he said he’s found is outside of Jackson in the suburbs. The couple doesn’t have a car.

Making rent every month usually depends on their ability to find someone to help chip in, said Ivy, who is in recovery from substance abuse. She said she’s watched problems surrounding homelessness grow over the years in Jackson. Ivy grew up near Stewpot and has lived in various neighborhoods across the city – except for the times she moved out of state when things got too rough.

“There was just moments where I just had to leave,” Ivy said. “Sometimes if you hit a slump here, there’s almost no way for you to get out of it.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post 'You're not going to be able to do that anymore': Jackson police chief visits food kitchen to discuss new public sleeping, panhandling laws appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Right

This article primarily reports on new laws in Jackson, Mississippi, targeting public sleeping, panhandling, and squatting, focusing on statements by Police Chief Joseph Wade and community perspectives. The coverage presents the legislative measures—authored by Republican and independent lawmakers—with a tone that emphasizes law enforcement challenges and community safety, reflecting a conservative approach to homelessness as a public order issue. While it includes voices concerned about criminalization and the need for social support, the overall framing centers on law enforcement and property protection. The article maintains factual reporting without overt editorializing but leans slightly toward a center-right perspective by highlighting legal enforcement as a solution.

Mississippi Today

Medicaid cuts could be devastating for the Delta and the rest of rural America

Note: This story first published in Stateline, which is part of States Newsroom, the nation’s largest state-focused nonprofit news organization.

LAKE PROVIDENCE, La. — East Carroll Parish sits in the northeastern corner of Louisiana, along the winding Mississippi River. Its seat, Lake Providence, was a thriving agricultural center of the Delta. Now, the town is a shell of its former self. Charred and dilapidated buildings dot the small city center. There are a few gas stations, a handful of restaurants — and little to no industry.

Mayor Bobby Amacker, 79, says at one point “you couldn’t even walk down the street” in Lake Providence’s main business district because “there were so many people.”

“It’s gone down tremendously in the last 50 years,” said Amacker, a Democrat. “The town, it looks like it’s drying up. And it’s almost unstoppable, as far as I can tell.”

Now, East Carroll residents stand to lose even more. Like many people in Louisiana, they received a lifeline when the state expanded Medicaid to more low-income adults in 2016. Expansion drove Louisiana’s uninsured rate to the lowest in the Deep South, at 8% in 2023 for working-age adults, according to state data, despite it having the highest poverty rate in the U.S. that year.

This week, both chambers of Congress approved President Donald Trump’s “big, beautiful” tax and spending bill. It includes more than $1 trillion in cuts to Medicaid, the joint state-federal health insurance program for poor families and individuals, to help pay for tax cuts that mostly benefit the rich. The legislation would cause 11.8 million more Americans to become uninsured by 2034, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

The bill includes new work rules for Medicaid recipients and would require them to verify their eligibility more frequently. It also would limit a financing strategy that states have used to boost Medicaid payments to hospitals.

Republicans say enrollees are taking advantage of the Medicaid program and getting benefits when they shouldn’t be. They say the program costs too much and states are not paying their fair share.

The Delta region, which includes communities in both Louisiana and Mississippi, would suffer under such large cuts. But in Louisiana — where almost half of the state depended on Medicaid in 2023, the Louisiana Department of Health reported — the cuts could be ruinous. Louisiana could lose up to $35 billion in federal Medicaid support over the next decade, according to KFF, a health policy research group. Mississippi, which never expanded Medicaid, could still lose up to $5 billion.

Residents are watching with apprehension, fear and, sometimes, anger, wondering how Congress could be so blind to how much they are struggling.

“If they take that away from us and everyone that really needs it, that’s going to be bad,” said Sherila Ervin, who lives 20 minutes up the road from Lake Providence in Oak Grove and has Medicaid coverage.

Medicaid work requirements and other health care provisions in the bill ignore the reality of living in poorer rural communities, where people struggle to find the jobs, transportation and internet access required to meet the rules, according to interviews with people and providers in the Delta region.

Even though Louisiana and Mississippi have taken very different approaches to Medicaid — one expanded eligibility under the 2010 Affordable Care Act and the other didn’t — both rely heavily on the program to sustain access to medical care for all their residents.

On a hot summer day in June, Ervin walks into the bare-bones 99-cent store in downtown Lake Providence. As she looks over some clothing, she says she’s heard about the potential Medicaid cuts. But she hadn’t heard about the work requirements, and is shocked they’re even on the table.

“I don’t like that. I don’t think they should put a stipulation on that,” Ervin says, exasperated that she would have to report her work hours. It’s hard enough as it is, she says, to thrive in this community.

READ MORE: In the Deep South, health care fights echo civil rights battles

Ervin, 58, has been working at Oak Grove High School in the cafeteria, serving hot plates to children for two decades. She says it’s one of the good, steady jobs available in this area, but her income is only around $1,500 per month.

Ervin’s job offers health benefits, but she can’t afford the premiums on her salary. She relies on Medicaid for care, including medications for her high blood pressure.

In East Carroll Parish, around 46.5% of people live below the poverty level, meaning the area is overwhelmingly poor, at over four times the national poverty rate, with a median income of $28,321. For Black households, the figure is a mere $16,690.

Expansion was a lifeline for people such as Ervin. Louisiana offers Medicaid to people who earn below 138% of the federal poverty line — currently about $22,000 a year for an individual.

“Sometimes you can work, but then when you work, you still can’t pay to get help,” Ervin said.

It’s a similar economic situation an hour away across the river. Poverty is about three times the national rate in Washington County, Mississippi, where residents in the city of Greenville lament the consequences of not being able to avoid destructive medical debt, which can keep them stuck in a cycle of gig work and of living paycheck to paycheck.

Greenville, the county seat, is among the fastest-shrinking cities in the U.S. It’s still one of the larger rural cities in Mississippi, with coffee shops, restaurants, hotels, a regional hospital and several big-box stores. But the downtown has just a few small businesses and a bank, and residents say jobs are hard to find.

Greenville resident April McNair, 45, remembers giving birth 17 years ago, long before Mississippi extended postpartum Medicaid to a full year. She had Medicaid coverage during pregnancy, but was kicked off shortly after giving birth, despite having post-delivery complications.

The result was a trip to the emergency room and a $2,500 bill she couldn’t cover. Right after giving birth, McNair looked for work. She said potential employers often told her that she was overqualified because she had a master’s degree.

“I had to kind of figure out how to make my ends meet,” McNair said. “I ended up with a significant bill, all because I did not have Medicaid.”

McNair feels like Mississippi leaders are making a mistake by continuing to reject full Medicaid expansion.

“That’s a selfish move. To me, they’re selfish,” McNair said, adding that now she’s worried for neighbors in Louisiana who may lose the lifeline she wishes she had.

“God forbid, hypothetically speaking, what if one of them meets their demise because of this bill that [Congress] passed?”

Hard to thrive

Mississippi experienced its first taste of equalized access to medicine in the late 1960s.

Delta Health Center, the first federally funded health center in the nation, opened during the peak of the Civil Rights Movement in the all-Black town of Mound Bayou, about an hour north of Greenville. The center vowed to care for anyone regardless of race or ability to pay in a region plagued with poverty, poor health and discrimination — and continues to do so to this day.

It was a significant opportunity for generations of African Americans who had gone without health care, in a place where people had no access to clean drinking water, running sewage systems or even food, said Robin Boyles, chief program planning and development officer at Delta Health Center.

But it wasn’t easy for the clinic to mobilize support, even though it was clearly needed. Before its opening, it faced pushback from politicians and even doctors. In a 1966 clipping from a local newspaper, the white-owned Bolivar Commercial, the editorial board railed against the new clinic, saying it would “lead further to socialized medicine.”

The situation is certainly better in Mississippi and Louisiana than it was in the 1960s, but critics say the Medicaid cuts could reverse hard-fought progress.

People who live in the Delta are fiercely proud of their communities, but conditions there make it hard to thrive.

Black residents, who are the overwhelming majority, have had a particularly hard time. After the Civil War, many were relegated to sharecropping of cotton and corn for subsistence. Meanwhile, an elite white class of plantation owners and investors amassed enormous amounts of wealth.

A 2001 report from the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights described the area as one with “limited economic resources; inadequate employment opportunities; insufficient decent, affordable housing; and poor quality public schools.”

“We have a lot of patients that are one health issue away from either being out of a job or being bankrupt because of a trip to the emergency room,” said Dr. Brent Smith, a physician at a primary care clinic at Delta Health System in Greenville.

Even some of the most vulnerable people, such as new moms in Mississippi, still struggle to get basic care, in part because the state has left billions of dollars in federal funding for Medicaid expansion on the table, said Dr. Lakeisha Richardson, an OB-GYN at Delta Health System.

“There are a lot of maternal [care] deserts in Mississippi where women have to travel 60 miles or more just to get prenatal care and just to get to the closest hospital for delivery,” Richardson said. “And I don’t see that getting any better in Mississippi and in rural areas.”

Richardson says nearly all her patients are working moms, many of whom would really benefit from having Medicaid expansion.

“America doesn’t realize that there are people out here struggling for no reason of their own,” she said.

That’s why Medicaid expansion in Louisiana in 2016, much like the community health center movement in Mississippi, was a bright spot in the rural South, said Smith.

“Louisiana expanded Medicaid, a surprising move in the South to see any state expand,” Smith said. “They saw it for what it was, which was a very real opportunity to assist this specific group of patients.”

In Mississippi, 20 rural hospitals are at immediate risk of closure, according to a recent report, more than double the number at risk in Louisiana. In many cases, Medicaid is the largest and most reliable payer for rural hospitals. While Louisiana’s overall uninsured rate plummeted to 8.3% by 2023, in Mississippi it was 10.5%.

“Unlike a lot of our Southern peers, we have not had the same level of closures of facilities,” said Courtney Foster, senior policy adviser for Medicaid, with the nonprofit Invest in Louisiana.

“Medicaid was like a real lifeline for people in transition. Oftentimes it was people who had lost their jobs and were just looking to get back on their feet.”

Now, the new work and reporting requirements could put that progress at risk.

In East Carroll Parish, finding a job — let alone a good-paying one with health benefits — is difficult, says Rosie Brown, executive director at the East Carroll Community Action Agency, a nonprofit that helps low-income people with their rent and utility bills. Many of the jobs available in town pay minimum wage, just $7.25 an hour.

Brown loves living in Lake Providence; this is where her family is. She doesn’t want to move but wishes the government would invest more in her community — not take away benefits that help people who are hanging on by a thread.

“We have one bank. We have one supermarket,” she said. “Transportation isn’t easy either.”

Local infrastructure is so limited, she’s even heard of some people charging residents $20 for a ride to Walmart. Some people have to hitch a ride an hour away to go to work, she said.

“There’s nowhere to go,” Brown said.

Dominique Jones works at the local library, where she helps roughly 75 to 85 people per month apply for programs such as Medicaid and food assistance. Many of the residents she helps don’t have access to the internet or even a computer, a real barrier for people who’d be required to report their working hours to state Medicaid officials.

“This town right here is made up of a lot of old people that need Medicaid and Medicare. And without it, they wouldn’t have any kind of health care at all,” Mayor Amacker said.

Even a job in local government in Lake Providence doesn’t offer affordable health insurance.

Nevada Qualls, 25, sits across from Amacker’s office. She earns just $12 an hour as a cashier at city hall. The low pay means she qualifies for Medicaid expansion coverage, which is good because she can’t afford the premiums for private insurance.

“I feel like there should be a higher threshold for people that can get Medicaid, because they’re still struggling,” she said.

At the 99-cent store, school district worker Ervin wonders whether state and federal leaders understand what it’s like to live in her community, urging them to visit and see for themselves.

“They want to do stuff for the rich people that’s already rich,” she said. “What are they doing? It’s almost like there’s no common sense with them.”

‘The tremble factors’

While leaders in the U.S. Senate were working into the night this past weekend debating Trump’s tax and spending bill, Greenville resident Jennifer Morris was praying for the pain to stay away.

Morris, 44, has hemicrania continua, a headache disorder that causes constant pain on one side of her head. There’s no underlying trigger and no cure. Her doctors help her keep the pain to a minimum with regular treatments that include dozens of injections into her head.

“It doesn’t take the pain away,” she said during a late-night gathering in Greenville’s Greater Mount Olivet Missionary Baptist Church in June. “It does reduce the pain so that I’m able to function. But it’s rough.”

Morris is worried about the looming Medicaid cuts. She qualifies for Mississippi Medicaid because her condition counts as a disability, and she depends on the coverage to afford her medications.

Morris’ Medicaid may be safer than that of her Delta neighbors in Lake Providence, as some of the most dramatic Medicaid changes being considered — such as work requirements — target Medicaid expansion states only.

But Mississippi could be hurt by a provision in the Senate bill that would target a strategy states have used to boost the Medicaid dollars they get from the federal government.

Mississippi could see a major hit to its Medicaid funds, which “would be a tremendous decrease in revenue for the state,” harming “services and access to care,” says Mitchell Adcock, executive director at the Center for Mississippi Health Policy.

“It would be just the opposite of expansion. It would be a contraction for the Medicaid program in the state,” he said.

Leonard Favorite, a pastor who was attending the same event at Mount Olivet Church, as Morris, says he grew up on a plantation in Louisiana and worked his way out of poverty by joining the Air Force. This type of journey is hard, he said, when you’re already starting from so far behind. He thinks the “big, beautiful bill” will create more roadblocks for poor people.

READ MORE: Glaucoma-related vision loss is often preventable, but many can’t afford treatment

“You have people who are already living below the poverty line and they will certainly be submerged into poverty at unspeakable levels,” said Favorite, 70.“ That seems to be the trend of this administration from the point of view of looking from the outside.

“Poor people are beginning to feel the tremble factors of an administration that caters toward the rich.”

National researchers estimate that up to 132,000 Louisianans who gained health insurance under expansion could lose it under work rules.

But national reports that rely on census data likely underestimate the potential Medicaid losses. For example, while 2023 census data show 47% of East Carroll Parish was on Medicaid, state health data reviewed by Stateline and Public Health Watch suggests the number is more like 64%. Similarly statewide, census data showed about a third of Louisianans were on Medicaid. State data shows that percentage is closer to 46.5%.

Experts such as Joan Alker at the Georgetown Center for Children and Families say the undercounts nationally are a well-known issue among researchers, but it’s difficult to correct because the quality of state reporting can be so uneven.

State Medicaid funding is also at risk. For years, both Mississippi and Louisiana have relied on revenue generated through a financing tool — known as a provider tax — to draw down more federal dollars and boost Medicaid reimbursements to providers. But congressional Republicans hope to limit states’ ability to collect those taxes.

Depending on how Congress restricts provider taxes, Mississippi could lose hundreds of millions in federal Medicaid funding, crucial in a state with such a high uninsured rate, said Richard Roberson, president and CEO of the Mississippi Hospital Association.

“It’s unavoidable that when you’re taking that much money out of the system, that there’s not going to be some repercussions felt even in non-Medicaid expansion states like Mississippi,” Roberson said.

Last week, the Louisiana Hospital Association signed a statement calling the package of Medicaid cuts before Congress “historic in their devastation.”

From her small, sunny office in East Carroll Parish, nurse Jennifer Newton can’t understand the attacks on Medicaid.

Newton, who grew up one parish over in West Carroll, is executive director of the Family Medical Clinic, a community health center in Lake Providence and one of the few health providers in town. She says 50% of the clinic’s patients have Medicaid insurance.

Newton has worked in health care in the area for decades and watched as Medicaid expansion made it possible for more patients to access and afford health care they desperately needed, including preventive services. “It’s absolutely helped,” she said. “Absolutely.”

In 2015, the year before Louisiana expanded Medicaid, the uninsured rate among working-age adults in East Carroll Parish was nearly 35%. By 2021, that number was 12.7%.

“Why are we going back?” Newton asked. “We’ve made so much progress.”

Republican supporters of work requirements, including Louisiana representative and U.S. House Speaker Mike Johnson, argue they will encourage people to find jobs and ensure Medicaid goes to people who need it most. But according to KFF, a majority of Louisiana adults with Medicaid — 69% — already work.

Brian Blase, president of the Paragon Health Institute, a conservative policy group that is working with Republicans to formulate Medicaid cuts, is not concerned about eligible people losing coverage, as has happened under previous work requirement efforts. He says the bill has built in exceptions for certain people and requirements “can be met by not just work,” so “concerns seem pretty overstated.”

Medicaid recipients also can meet the requirement by volunteering or attending school for 80 hours per month.

“It’s hard for me to understand that there are areas in the country where there’s not jobs. There’s always work to be done,” Blase told Stateline. Blase said he believes Medicaid is “the government conditioning welfare for able-bodied working-age adults.”

But advocates and experts predict East Carroll, where internet access is notoriously bad, would experience results similar to when Arkansas instituted Medicaid work requirements in 2018: People disenrolled because of lack of awareness and confusion over the policy, as well as paperwork errors — not because they weren’t working enough.

“Unless the beneficiary can navigate that red tape, they’re going to lose coverage and become uninsured,” said Benjamin Sommers, a health economist at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Data shows Arkansas’ experiment did not increase employment, Sommers said, and instead led to more people reporting medical debt and delaying care because of cost.

‘Take a step back’

People in the Delta — where the legacy of government neglect and discrimination are all around — want politicians to visit their towns and see the barriers people face trying to improve their lives and stay healthy.

“People spent their lives uninsured,” said Amy Hale, a nurse practitioner at East Carroll Medical clinic. “Medicaid expansion allowed them to get in here and be treated.”

Lake Providence residents are scared they may find themselves in a similar situation as McNair and other people across the river in Greenville: working, uninsured, and too poor to access health care.

Recent estimates show up to 317,000 Louisianans could lose Medicaid health insurance under Trump’s tax bill. Nearly 33,000 in Mississippi.

“People are actually trying,” McNair said. “I really wish [lawmakers] would look at it from a different lens. What if it was their kid? Or they didn’t have the salaries they have now and your baby is ill. … Like really take a step back and think about what it is that you’re doing.”

This story is part of “Uninsured in America,” a project led by Public Health Watch that focuses on life in America’s health coverage gap and the 10 states that haven’t expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

Stateline reporter Shalina Chatlani can be reached at schatlani@stateline.org. Public Health Watch reporter Kim Krisberg can be reached at kkrisberg@publichealthwatch.org.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Medicaid cuts could be devastating for the Delta and the rest of rural America appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

The article presents a clear perspective sympathetic to low-income and rural communities affected by Medicaid cuts. It highlights the hardships faced by residents in Louisiana’s and Mississippi’s Delta regions, emphasizing poverty, limited job opportunities, and the critical role Medicaid plays in health access. While it reports Republicans’ arguments for work requirements and cost control, the language and framing focus more on the negative consequences of cuts and the struggles of vulnerable populations. This tone and focus suggest a center-left bias, favoring expanded social safety nets and critical of policies perceived to harm the poor.

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

Real-life Uncle Sam's descendants live in Arkansas

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed7 days ago

Her son faced 10 years behind bars; now she’s the one facing prison

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

Could roundabouts become more common than red lights?

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed5 days ago

'Big Beautiful Bill' already felt at Georgia state parks | FOX 5 News

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days ago

LOFT report uncovers what led to multi-million dollar budget shortfall

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

Alabama schools to lose $68 million in federal grants under Trump freeze

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

Celebrate St. Louis returns with new Superman-themed drone show

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed6 days ago

Officers run for cover after man in car fired shots at them in Downtown Memphis