Douglas Rissing/iStock / Getty Images Plus

Colin Gordon, University of Iowa

For much of the 20th century, efforts to remake government were driven by a progressive desire to make the government work for regular Americans, including the New Deal and the Great Society reforms.

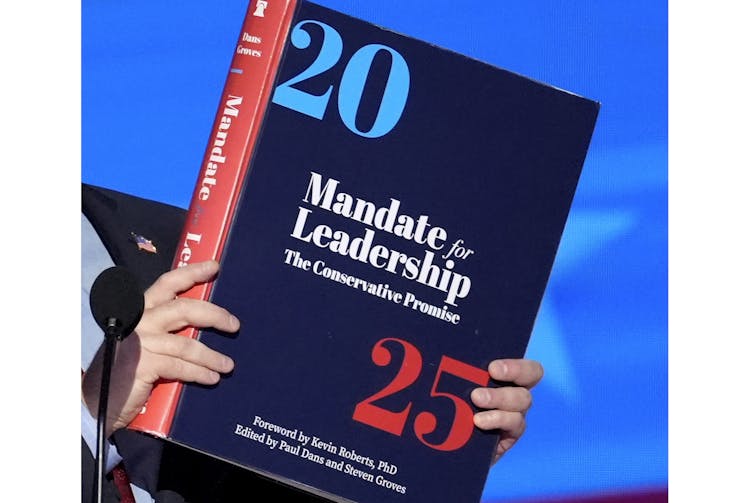

But they also met a conservative backlash seeking to rein back government as a source of security for working Americans and realign it with the interests of private business. That backlash is the central thread of the Heritage Foundation’s “Project 2025” blueprint for a second Trump Administration.

Alternatively disavowed and embraced by President Donald Trump during his 2024 campaign, Project 2025 is a collection of conservative policy proposals – many written by veterans of his first administration. It echoes similar projects, both liberal and conservative, setting out a bold agenda for a new administration.

But Project 2025 does so with particular detail and urgency, hoping to galvanize dramatic change before the midterm elections in 2026. As its foreword warns: “Conservatives have just two years and one shot to get this right.”

The standard for a transformational “100 days” – a much-used reference point for evaluating an administration – belongs to the first administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

AP Photo, file

Social reforms and FDR

In 1933, in the depths of the Great Depression, Roosevelt faced a nation in which business activity had stalled, nearly a third of the workforce was unemployed, and economic misery and unrest were widespread.

But Roosevelt’s so-called “New Deal” unfolded less as a grand plan to combat the Depression than as a scramble of policy experimentation.

Roosevelt did not campaign on what would become the New Deal’s singular achievements, which included expansive relief programs, subsidies for farmers, financial reforms, the Social Security system, the minimum wage and federal protection of workers’ rights.

Those achievements came haltingly after two years of frustrated or ineffective policymaking. And those achievements rested less on Roosevelt’s political vision than on the political mobilization and demands made by American workers.

A generation later, another wave of social reforms unfolded in similar fashion. This time it was not general economic misery that spurred actions, but the persistence of inequality – especially racial inequality – in an otherwise prosperous time.

LBJ’s Great Society

President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society programs declared a war on poverty and, toward that end, introduced a raft of new federal initiatives in urban, education and civil rights.

These included the provision of medical care for the poor and older people via Medicaid and Medicare, a dramatic expansion of federal aid for K-12 education, and landmark voting rights and civil rights legislation.

As with the New Deal, the substance of these policies rested less with national policy designs than with the aspirations and mobilization of the era’s social movements.

Resistance to policy change

Since the 1930s, conservative policy agendas have largely taken the form of reactions to the New Deal and the Great Society.

The central message has routinely been that “big government” has overstepped its bounds and trampled individual rights, and that the architects of those reforms are not just misguided but treasonous. Project 2025, in this respect, promises not just a political right turn but to “defeat the anti-American left.”

After the 1946 midterm elections, congressional Republicans struck back at the New Deal. Drawing on business opposition to the New Deal, popular discontent with postwar inflation, and common cause with Southern Democrats, they stemmed efforts to expand the New Deal, gutting a full employment proposal and defeating national health insurance.

They struck back at organized labor with the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, which undercut federal law by allowing states to pass anti-union “right to work” laws. And they launched an infamous anti-communist purge of the civil service, which forced nearly 15,000 people out of government jobs.

In 1971, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce commissioned Lewis Powell – who would be appointed by Republican President Richard Nixon to the Supreme Court the next year – to assess the political landscape. Powell’s memorandum characterized the political climate at the dawn of the 1970s – including both Great Society programs and the anti-war and Civil Rights movements of the 1960s – as nothing less than an “attack on the free enterprise system.”

In a preview of current U.S. politics, Powell’s memorandum devoted special attention to a disquieting “chorus of criticism” coming from “the perfectly respectable elements of society: from the college campus, the pulpit, the media, the intellectual and literary journals, the arts and sciences, and from politicians.”

Powell characterized the social policies of the New Deal and Great Society as “socialism or some sort of statism” and advocated the elevation of business interests and business priorities to the center of American political life.

AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite

Building a conservative infrastructure

Powell captured the conservative zeitgeist at the onset of what would become a long and decisive right turn in American politics. More importantly, it helped galvanize the creation of a conservative infrastructure – in the courts, in the policy world, in universities and in the media – to push back against that “chorus of criticism.”

This political shift would yield an array of organizations and initiatives, including the political mobilization of business, best represented by the emergence of the Koch brothers and the powerful libertarian conservative political advocacy group they founded, known as Americans for Prosperity. It also yielded a new wave of conservative voices on radio and television and a raft of right-wing policy shops and think tanks – including the Heritage Foundation, creator of Project 2025.

In national politics, the conservative resurgence achieved full expression in President Ronald Reagan’s 1980 campaign. The “Reagan Revolution” united economic and social conservatives around the central goal of dismantling what was left of the New Deal and Great Society.

Powell’s triumph was evident across the policy landscape. Reagan gutted social programs, declared war on organized labor, pared back economic and social regulations – or declined to enforce them – and slashed taxes on business and the wealthy.

Publicly, the Reagan administration argued that tax cuts would pay for themselves, with the lower rates offset by economic growth. Privately, it didn’t matter: Either growth would sustain revenues, or the resulting budgetary hole could be used to “starve the beast” and justify further program cuts.

Reagan’s vision, and its shaky fiscal logic, were reasserted in the “Contract with America” proposed by congressional Republicans after their gains in the 1994 midterm elections.

This declaration of principles proposed deep cuts to social programs alongside tax breaks for business. It was perhaps most notable for encouraging the Clinton administration to pass the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act of 1996, “ending welfare as we know it,” as Clinton promised.

Aiming at the ‘deep state’

Project 2025, the latest in this series of blueprints for dramatic change, draws most deeply on two of those plans.

As in the congressional purges of 1940s, it takes aim not just at policy but at the civil servants – Trump’s “deep state” – who administer it.

In the wake of World War II, the charge was that feckless bureaucrats served Soviet masters. Today, Project 2025 aims to “bring the Administrative State to heel, and in the process defang and defund the woke culture warriors who have infiltrated every last institution in America.”

As in the 1971 Powell memorandum, Project 2025 promises to mobilize business power; to “champion the dynamic genius of free enterprise against the grim miseries of elite-directed socialism.”

Whatever their source – party platforms, congressional bomb-throwers, think tanks, private interests – the success or failure of these blueprints rested not on their vision or popular appeal but on the political power that accompanied them. The New Deal and Great Society gained momentum and meaning from the social movements that shaped their agendas and held them to account.

The lineage of conservative responses has been largely an assertion of business power. Whatever populist trappings the second Trump administration may possess, the bottom line of the conservative cultural and political agenda in 2025 is to dismantle what is left of the New Deal or the Great Society, and to defend unfettered “free enterprise” against critics and alternatives.

Colin Gordon, Professor of History, University of Iowa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.