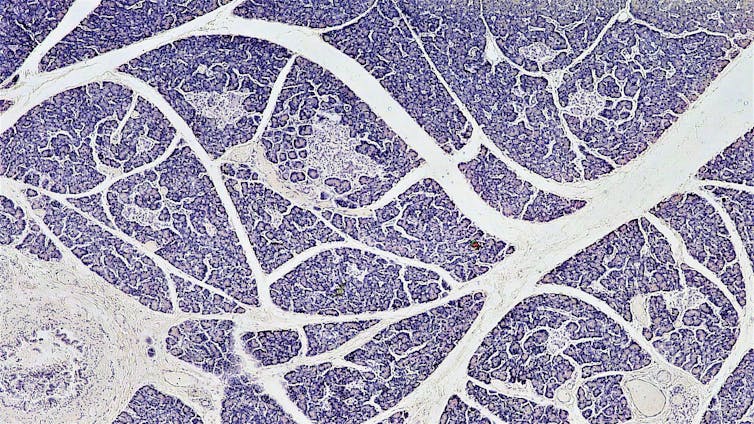

Fayette A Reynolds/Berkshire Community College Bioscience Image Library via Flickr

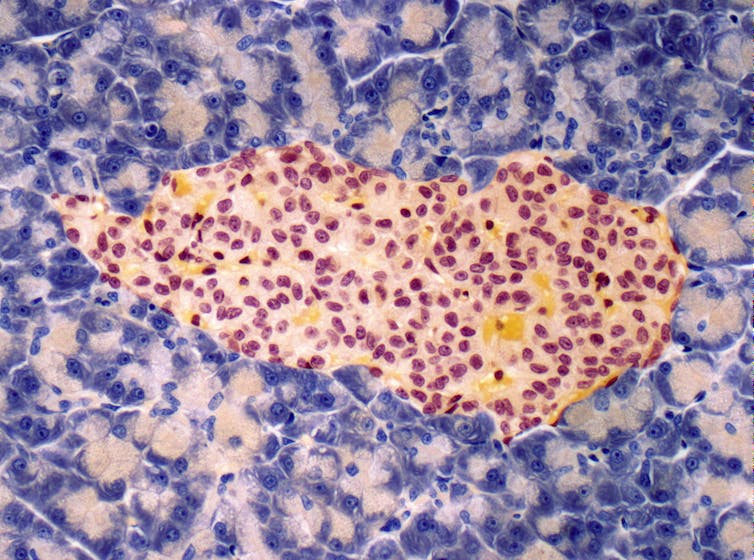

Vinny Negi, University of Pittsburgh

Diabetes develops when the body fails to manage its blood glucose levels. One form of diabetes causes the body to not produce insulin at all. Called Type 1 diabetes, or T1D, this autoimmune disease happens when the body’s defense system mistakes its own insulin-producing cells as foreign and kills them. On average, T1D can lead patients to lose an average of 32 years of healthy life.

Current treatment for T1D involves lifelong insulin injections. While effective, patients taking insulin risk developing low blood glucose levels, which can cause symptoms such as shakiness, irritability, hunger, confusion and dizziness. Severe cases can result in seizures or unconsciousness. Real-time blood glucose monitors and injection devices can help avoid low blood sugar levels by controlling insulin release, but they don’t work for some patients.

For these patients, a treatment called islet transplantation can help better control blood glucose by giving them both new insulin-producing cells as well as cells that prevent glucose levels from falling too low. However, it is limited by donor availability and the need to use immunosuppressive drugs. Only about 10% of T1D patients are eligible for islet transplants.

In my work as a diabetes researcher, my colleagues and I have found that making islets from stem cells can help overcome transplantation challenges.

History of islet transplantation

Islet transplantation for Type 1 diabetes was FDA approved in 2023 after more than a century of investigation.

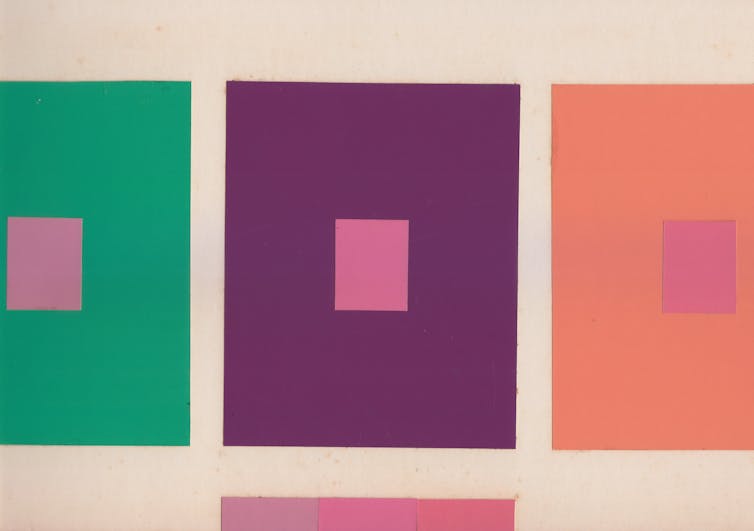

Insulin-producing cells, also called beta cells, are located in regions of the pancreas called islets of Langerhans. They are present in clusters of cells that produce other hormones involved in metabolism, such as glucagon, which increases blood glucose levels; somatostatin, which inhibits insulin and glucagon; and ghrelin, which signals hunger. Anatomist Paul Langerhans discovered islets in 1869 while studying the microscopic anatomy of the pancreas, observing that these cell clusters stained distinctly from other cells.

The road to islet transplantation has faced many hurdles since pathologist Gustave-Édouard Laguesse first speculated about the role islets play in hormone production in the late 19th century. In 1893, researchers attempted to treat a 13-year-old boy dying of diabetes with a sheep pancreas transplant. While they saw a slight improvement in blood glucose levels, the boy died three days after the procedure.

Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library via Getty Images

Interest in islet transplantation was renewed in 1972, when scientist Paul E. Lacy successfully transplanted islets in a diabetic rat. After that, many research groups tried islet transplantation in people, with no or limited success.

In 1999, transplant surgeon James Shapiro and his team successfully transplanted islets in seven patients in Edmonton, Canada, by transplanting a large number of islets from two to three donors at once and using immunosuppressive drugs. Through the Edmonton protocol, these patients were able to manage their diabetes without insulin for a year. By 2012, over 1,800 patients underwent islet transplants based on this technique, and about 90% survived through seven years of follow-up. The first FDA-approved islet transplant therapy is based on the Edmonton protocol.

Stem cells as a source of islets

Islet transplantation is now considered a minor surgery, where islets are injected into a vein in the liver using a catheter. As simple as it may seem, there are many challenges associated with the procedure, including its high cost and a limited availability of donor islets. Transplantation also requires lifelong use of immunosuppressive drugs that allow the foreign islets to live and function in the body. But the use of immunosuppressants also increases the risk of other infections.

To overcome these challenges, researchers are looking into using stem cells to create an unlimited source of islets.

There are two kinds of stem cells scientists are using for islet transplants: embryonic stem cells, or ESCs, and induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPSCs. Both types can mature into islets in the lab.

Each has benefits and drawbacks.

There are ethical concerns regarding ESCs, since they are obtained from dead human embryos. Transplanting ESCs would still require immunosuppressive drugs, limiting their use. Thus, researchers are working to either encapsulate or make mutations in ESC islets to protect them from the body’s immune system.

Conversely, iPSCs are obtained from skin, blood or fat cells of the patient undergoing transplantation. Since the transplant involves the patient’s own cells, it bypasses the need for immunosuppressive drugs. But the cost of generating iPSC islets for each patient is a major barrier.

Stem cell islet challenges

While iPSCs could theoretically avoid the need for immunosuppressive drugs, this method still needs to be tested in the clinic.

T1D patients who have genetic mutations causing the disease currently cannot use iPSC islets, since the cells that would be taken to create stem cells may also carry the same disease-causing mutation of their islet cells. Many available gene-editing tools could potentially remove those mutations and generate functional iPSC islets.

In addition to the challenge of genetic tweaking, price is a major issue for islet transplantation. Transplanting islets made from stem cells is more expensive than insulin therapy because of higher manufacturing costs. Efforts to scale up the process and make it more cost effective include creating biobanks for iPSC matching. This would allow iPSC islets to be used for more than one patient, reducing costs by avoiding the need to generate freshly modified islets for each patient. Embryonic stem cell islets have a similar advantage, as the same batch of cells can be used for all patients.

There is also a risk of tumors forming from these stem cell islets after transplantation. So far, lab studies on rodents and clinical trials in people have rarely shown any cancer. This suggests the chances of these cells forming a tumor are low.

That being said, many rounds of research and development are required before stem cell islets can be used in the clinic. It is a laborious trek, but I believe a few more optimizations can help researchers beat diabetes and save lives.

Article updated to clarify that Type 1 diabetes causes the body to not produce insulin.![]()

Vinny Negi, Research Scientist in Endocrinology and Metabolism, University of Pittsburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.