Mississippi Today

This DeSoto Co. hospital transfers some patients to jail to await mental health treatment

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Mississippi Today and co-published with the Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal, the Sun Herald and MLK50. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

If you or someone you know needs help:

- Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988

- Text the Crisis Text Line from anywhere in the U.S. to reach a crisis counselor: 741741

When Sandy Jones’ 26-year-old daughter started writing on the walls of her home in Hernando, Mississippi, last year and talking angrily to the television, Sandy said, she knew two things: Her daughter Sydney needed help, and Sandy didn’t want her to be held in jail again to get it.

A year and a half earlier, during Sydney Jones’ first psychotic episode, her mother filed paperwork to have her involuntarily committed, a legal process in which a judge can order someone to receive mental health treatment. After DeSoto County sheriff’s deputies showed up at Sydney’s home and explained that they were detaining her for a mental evaluation, Sydney panicked and ran inside. Following a struggle, deputies cuffed and shackled her and drove her to the county jail, where people going through the commitment process are usually held as they await mental health treatment elsewhere.

Over nine days in jail, Sydney Jones said, she believed her tattoos were portals for spiritual forces and felt like she had been abandoned by her family. In an interview, she said that the experience was so traumatic that she became anxious when she drove, afraid she could be arrested at any moment.

The second time Sydney Jones experienced delusions, in 2023, a family member contacted the local community mental health center for help. Police officers with mental health training came and called an ambulance to take Jones to Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto, part of a large, religiously affiliated nonprofit hospital system. But because the hospital doesn’t have a psychiatric unit, after a few days it sent her to the jail to wait for eventual treatment in a publicly funded facility. Like the first time, she hadn’t been charged with a crime.

Roughly 200 people in DeSoto County were jailed annually during the civil commitment process, most without criminal charges, between 2021 and 2023. About a fifth of them were picked up at local hospitals, according to an estimate based on a review of Sheriff’s Department records by Mississippi Today and ProPublica. The overwhelming majority of those patients, according to our analysis, were at Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto, the largest in this prosperous, suburban county near Memphis.

“That would just be unthinkable here,” said Dr. Grayson Norquist, the chief of psychiatry at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta, a professor at Emory University and the former chair of psychiatry at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, Mississippi.

Norquist was one of 17 physicians specializing in emergency medicine or psychiatry, including leaders in their fields, who said they had never heard of a hospital sending patients to jail solely to wait for mental health treatment. Several said it violates doctors’ Hippocratic oath: to do no harm.

The practice appears to be unusual even in Mississippi, where lawmakers recently acted to limit when people can be jailed as they go through the civil commitment process. Sheriff’s departments in about a third of the state’s counties, including those that appear to jail such people most frequently, responded to questions from Mississippi Today and ProPublica about how they handle involuntary commitment. They said they seldom, if ever, take people who need mental health treatment from a hospital to jail. At most, said sheriffs in a few rural counties, they do it once or twice a month.

But in DeSoto County, hospital patients were jailed about 50 times a year from 2021 to 2023, according to the news outlets’ estimate, which was based on a review of Sheriff’s Department dispatch logs, incident reports and jail dockets.

At least two people have died soon after being taken from Baptist-DeSoto to a county jail during the commitment process, according to documents submitted for lawsuits filed over their deaths. One person died by suicide hours after arriving at the DeSoto County jail in 2021; the other died of multisystem organ failure after being jailed for three days in neighboring Marshall County in 2011. James Franks, an attorney who handles commitments for DeSoto County, said officials had no reason to believe that the woman who killed herself was suicidal. DeSoto County made a similar argument in a court filing in an ongoing lawsuit over that death, which didn’t name the hospital as a defendant. In lawsuits over the other death, a judge dismissed Marshall County and the sheriff as defendants, and a jury found that Baptist-DeSoto wasn’t liable.

Baptist-DeSoto officials said the hospital hands some patients over to deputies to take them to jail because those patients need dedicated treatment that the hospital can’t provide and nearby inpatient facilities are full. Most people who need inpatient treatment agree to be transferred to a behavioral health facility, according to Kim Alexander, director of public relations for Baptist Memorial Health Care Corp. But in a relatively small number of cases, she wrote in an email, patients are deemed dangerous to themselves or others and don’t agree to treatment, so they need to be committed. When that happens, she said, it’s the county’s responsibility to decide where to house them.

“We discharge mental health patients with the hope they will be transferred to a mental health facility that can provide the specialized care they need,” Alexander wrote in a statement. Jailing people who need mental health care is “not the ideal option,” she wrote. “Our hearts go out to anyone who cannot access the mental health care they need because behavioral health services are not available in the area.”

But doctors elsewhere said even if psychiatric facilities are full, Baptist-DeSoto doesn’t have to send patients to jail. They said the hospital could do what hospitals elsewhere in the country do: keep patients until a treatment bed is available.

“This is a principle of emergency medicine: You care for all people, under all circumstances, at any time,” said Dr. Lewis Goldfrank, who spent 50 years working in emergency medicine, including at Bellevue Hospital in New York City. Sending patients to jail because of their illness, he said, “is just unethical and irresponsible.”

Sandy Jones said she was in disbelief when it happened to her daughter. If Sydney has another psychotic episode, Sandy Jones said she won’t try to get help in DeSoto County. “I will tie her up until it’s over.”

Headed to Jail in a Hospital Gown and Handcuffs

Baptist, the largest and oldest hospital in DeSoto County, sits right off the interstate amid big-box stores and chain hotels in Southaven, Mississippi. It’s the first place many residents think of when they need medical help. Since 2017, it has served as the drop-off point for the county’s crisis intervention team, which was established to give law enforcement a way to help people with mental illness without bringing them to jail.

But when people show up in the emergency department needing inpatient psychiatric treatment, they don’t get it at Baptist-DeSoto. Instead, a crisis coordinator sets about finding some other place for them. If patients agree to treatment, they may be able to go to a publicly funded crisis unit, the closest of which is 50 miles away, or to a private psychiatric hospital. If they don’t, the crisis coordinator pursues commitment, which means turning patients over to the Sheriff’s Department. And because the Sheriff’s Department usually won’t transport patients over a long distance multiple times for a court hearing and eventual treatment, those patients usually go to jail.

That was the case with Sydney Jones. After she arrived at the hospital in April 2023, a psychiatrist contracted by the hospital evaluated her and concluded that she needed inpatient treatment. Jones was prescribed antipsychotic medication, admitted to the hospital, placed in her own room and monitored by a security guard.

Meanwhile, a staffer for Region IV, the local nonprofit community mental health center that works with Baptist-DeSoto to place patients who need treatment, was trying to find someplace for Jones other than the hospital. Catherine Davis, the crisis coordinator, concluded that Jones would need to be committed.

The next day, Davis contacted Jones’ cousin, who had tried to get Jones help, and asked the cousin to initiate commitment proceedings. (Region IV’s contract with Baptist-DeSoto requires it to try to get a patient’s family member or friend to file commitment paperwork before doing so itself.) The cousin refused because she knew Jones would be jailed until a bed opened up, according to Sandy Jones. (The cousin declined an interview request.)

So Davis filed the commitment paperwork herself, writing that Sydney Jones “should be taken to DeSoto County jail” while awaiting further evaluations, a court hearing and eventual treatment.

On Sydney Jones’ fourth day at Baptist-DeSoto, two sheriff’s deputies arrived. They received discharge papers from a nurse and wheeled Jones out of the hospital, according to her and an incident report. Jones, who said her delusions at the time were “like if Satan made goggles and put them on you,” was terrified that the deputies would drive her to a field, rape her and kill her.

Sandy Jones said she didn’t understand why she had no say in what was happening to her daughter, although that’s typical during the commitment process. “I felt like she was kidnapped from me,” Sandy Jones said. Her daughter spent nine days in jail before being admitted to a crisis unit, where she was treated for about two weeks.

Mississippi Today and ProPublica interviewed five other people who were discharged from Baptist to jail, including two who had been taken to the hospital because they had attempted suicide. One said that when deputies came to his room, he wondered if he had somehow committed a crime after trying to kill himself by overdosing on prescription medication. Another said he felt humiliated to be wheeled through the hospital wearing just a hospital gown. Three of the five said they were handcuffed before being taken away.

Hospital officials noted that all patients are medically stabilized before being released and that some patients are committed by family members. Dr. H. F. Mason, Baptist-DeSoto’s chief medical officer, said in an interview that he didn’t know how often patients who need behavioral health treatment might be discharged to jail, but he has no concerns about the practice. When hospital staff hand patients over to local authorities, Mason said, “we feel that they’re going to take the appropriate care of that patient.”

The jail, however, offers minimal psychiatric treatment, if any. Region IV staff members visit the jail primarily to evaluate people going through the commitment process or to check on people on suicide watch, Region IV Director Jason Ramey said. Jail officials said medical staff try to make sure inmates have access to their prescription drugs, although some people jailed during commitment proceedings have said they didn’t consistently get their medications.

Davis and county officials involved in the commitment process said sending patients to jail as they await treatment is better than allowing them to go home, which they see as the only other option. Jail is “not ideal, but we’ve got to make sure these people are safe so they’re not going to harm themselves or somebody else,” Davis said. “If they’ve had a serious suicide attempt, and they’re just adamant they’re going home, I mean — I can’t ethically let them go home. … We do try to explore all the options before we send them there.”

Once in jail, many patients wait days or weeks to be evaluated further, to go before a judge and to be taken somewhere for treatment, according to a review of jail dockets. One 37-year-old man picked up at Baptist-DeSoto in 2022 was jailed for nearly two months, which according to jail dockets was one of the longest detentions between 2021 and 2023.

The husband of a 64-year-old woman said that during the evaluation process he was encouraged by someone at Baptist-DeSoto — he doesn’t remember who — to pursue commitment proceedings after his wife stopped taking her bipolar disorder medication and overdosed on prescription drugs and alcohol. She was jailed for 28 days.

“I’m a Jehovah’s Witness,” said the woman, who asked not to be identified because she doesn’t want people to know she was jailed for mental illness. “I never known anything like that in my life. Never been arrested. All my rights just stripped from me. To do that to an old woman, because I was having mental troubles!”

She said the experience left her terrified to seek mental health care in DeSoto County. “I’d rather die than go back in there,” she said of the jail.

DeSoto County Struggles with a Problem Other Communities Have Addressed

Although DeSoto County has long relied on its jail to house people awaiting treatment, some communities elsewhere in the state have found other options. They rely on nearby crisis units to provide short-term treatment and in many cases have arrangements with local hospitals to treat patients if a publicly funded bed isn’t available.

On the Gulf Coast, people who come to hospitals in Ocean Springs or Pascagoula can be admitted to an eight-bed psychiatric unit, said Kim Henderson, director of emergency services for Singing River Health System, which operates those facilities.

Henderson said the psychiatric unit loses money because many patients lack insurance and can’t pay. “It would be so much easier to say we’re not going to do this anymore and shut it down,” she said. “But we don’t believe that’s the right thing to do.”

Over the years, DeSoto County officials have expressed frustration with how many people are jailed during the commitment process, but they’ve made little progress in coming up with an alternative.

In 2007, Baptist-DeSoto initiated 152 commitments, according to board meeting minutes and a news story in the DeSoto Times-Tribune; many of those patients went to jail. The hospital sends people “as quickly as they can to the Sheriff’s Department. They want them out of there,” Michael Garriga, then the county administrator, said at the time, according to another Times-Tribune article. (The news stories didn’t include a comment from the hospital; Alexander, Baptist’s spokesperson, said she couldn’t comment on practices from years ago because no one who was part of the leadership team then is still around.)

In 2008, the CEO of Parkwood Behavioral Health System, which operates a psychiatric facility in the county, offered to treat people going through the commitment process for $465 per patient per day — many times more than the $25 a day it cost back then to house someone in jail. No contract was ever signed.

Two years later, again aiming to reduce how often people awaiting mental health treatment were jailed, DeSoto County started working with a different community mental health center, Region IV. The number of people held in jail during commitment proceedings fell sharply, but within several years it had risen.

In 2021, the state Department of Mental Health said it would give Region IV money to create a crisis unit in DeSoto, the largest county in the state without one. But the county must provide the building, and it has taken about two years just to move forward with a location, according to meeting minutes.

County officials considered putting the crisis unit in a building a few miles from the hospital and even got an architect to scope out a renovation, according to meeting minutes. By 2023, those plans had been scuttled amid concerns about the cost of renovations and opposition from neighbors, according to Mark Gardner, a county supervisor, and board meeting minutes.

Former Sheriff Bill Rasco said he was told by an alderman for the city of Southaven that residents didn’t want people with mental illness in their neighborhood. Rasco, who served from 2008 through 2023, said he believes the rapidly growing county has had the means to build a facility, but supervisors prioritize paving roads and keeping taxes low. “We build agricultural arenas, walking trails and ballfields, and we let our mental health suffer,” he said.

The county Board of Supervisors inched forward again in February, voting to hire an architect to draw up plans to renovate a different county building. But construction on the 16-bed facility won’t start until spring 2025 at the earliest.

Gardner, who was first elected in 2011, said he has always believed that people with mental illness shouldn’t be jailed, but the Sheriff’s Department and Region IV didn’t propose an alternative until recently. “We need it today,” he said. “I hate that we haven’t been able to find a suitable place till now to put this.”

A year after Sydney Jones’ second psychotic episode, she’s doing better. She hasn’t experienced another mental health crisis. The sight of a police cruiser no longer triggers a panic attack, though she does get anxious when she sees one in her neighborhood.

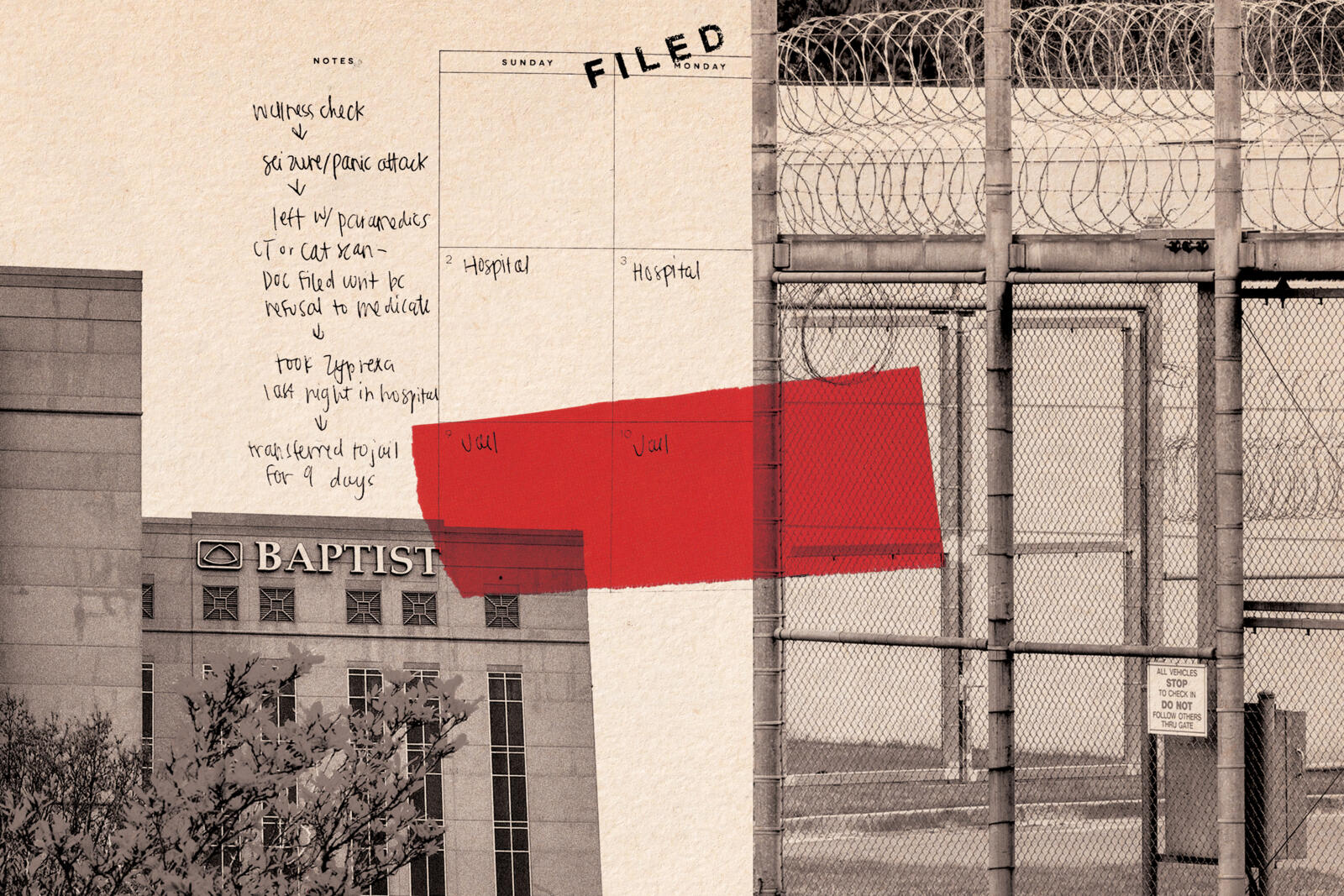

But she wants to remind herself of what she survived to get here, so she keeps mementos. The composition book where she wrote notes during group therapy at the crisis unit. The Bible she read in jail. The planner where she wrote “Hospital” in one square and “Jail” in the next. And two plastic wristbands: The white one identified her as a hospital patient; the yellow one, with her mug shot and booking number, identified her as a prisoner.

How We Reported This Story

To report this story, we obtained DeSoto County Sheriff’s Department logs from 2021 through 2023 that showed when deputies were called to two local hospitals to take people into custody for involuntary commitment proceedings to receive treatment for mental illness or substance abuse. Those logs included nearly 200 calls, mostly to Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto.

To determine which calls resulted in jail detentions, we needed to cross-reference the logs with incident reports and county jail dockets. We requested incident reports for about half of calls from 2021 through 2023. Although this sample wasn’t collected at random, we requested records from a range of months to account for possible variations throughout the year. Patients’ names were redacted from incident reports, but by using other identifying information in those reports, we matched 76% of the call logs in our sample to an entry in jail dockets. The remaining calls included not just those for which we couldn’t match an incident report to a jail docket entry, but also those for which there was no incident report or the patient was taken to a crisis unit or a private psychiatric hospital.

Based on that percentage and the volume of calls during the three-year period, we estimated that about 23% of the roughly 650 people jailed during the civil commitment process in DeSoto County had been picked up at a local hospital. Again, the overwhelming majority were taken from Baptist-DeSoto. To ensure that our estimate was conservative and accounted for any variation due to our sample, we characterized this as about one-fifth of civil commitment jail detentions. We shared our preliminary findings with hospital and county officials; no one disputed them.

To determine how the number of people jailed during commitment proceedings in DeSoto County has changed over time, we obtained jail dockets dating back to 2007. We don’t have data for 2009 and 2010 because of a file storage issue at the Sheriff’s Department.

Agnel Philip of ProPublica contributed reporting. Mollie Simon of ProPublica contributed research.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=362139

Mississippi Today

1964: Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was formed

April 26, 1964

Civil rights activists started the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to challenge the state’s all-white regular delegation to the Democratic National Convention.

The regulars had already adopted this resolution: “We oppose, condemn and deplore the Civil Rights Act of 1964 … We believe in separation of the races in all phases of our society. It is our belief that the separation of the races is necessary for the peace and tranquility of all the people of Mississippi, and the continuing good relationship which has existed over the years.”

In reality, Black Mississippians had been victims of intimidation, harassment and violence for daring to try and vote as well as laws passed to disenfranchise them. As a result, by 1964, only 6% of Black Mississippians were permitted to vote. A year earlier, activists had run a mock election in which thousands of Black Mississippians showed they would vote if given an opportunity.

In August 1964, the Freedom Party decided to challenge the all-white delegation, saying they had been illegally elected in a segregated process and had no intention of supporting President Lyndon B. Johnson in the November election.

The prediction proved true, with white Mississippi Democrats overwhelmingly supporting Republican candidate Barry Goldwater, who opposed the Civil Rights Act. While the activists fell short of replacing the regulars, their courageous stand led to changes in both parties.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Mississippi River flooding Vicksburg, expected to crest on Monday

Warren County Emergency Management Director John Elfer said Friday floodwaters from the Mississippi River, which have reached homes in and around Vicksburg, will likely persist until early May. Elfer estimated there areabout 15 to 20 roads underwater in the area.

“We’re about half a foot (on the river gauge) from a major flood,” he said. “But we don’t think it’s going to be like in 2011, so we can kind of manage this.”

The National Weather projects the river to crest at 49.5 feet on Monday, making it the highest peak at the Vicksburg gauge since 2020. Elfer said some residents in north Vicksburg — including at the Ford Subdivision as well as near Chickasaw Road and Hutson Street — are having to take boats to get home, adding that those who live on the unprotected side of the levee are generally prepared for flooding.

“There are a few (inundated homes), but we’ve mitigated a lot of them,” he said. “Some of the structures have been torn down or raised. There are a few people that still live on the wet side of the levee, but they kind of know what to expect. So we’re not too concerned with that.”

The river first reached flood stage in the city — 43 feet — on April 14. State officials closed Highway 465, which connects the Eagle Lake community just north of Vicksburg to Highway 61, last Friday.

Elfer said the areas impacted are mostly residential and he didn’t believe any businesses have been affected, emphasizing that downtown Vicksburg is still safe for visitors. He said Warren County has worked with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency to secure pumps and barriers.

“Everybody thus far has been very cooperative,” he said. “We continue to tell people stay out of the flood areas, don’t drive around barricades and don’t drive around road close signs. Not only is it illegal, it’s dangerous.”

NWS projects the river to stay at flood stage in Vicksburg until May 6. The river reached its record crest of 57.1 feet in 2011.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

With domestic violence law, victims ‘will be a number with a purpose,’ mother says

Joslin Napier. Carlos Collins. Bailey Mae Reed.

They are among Mississippi domestic violence homicide victims whose family members carried their photos as the governor signed a bill that will establish a board to study such deaths and how to prevent them.

Tara Gandy, who lost her daughter Napier in Waynesboro in 2022, said it’s a moment she plans to tell her 5-year-old grandson about when he is old enough. Napier’s presence, in spirit, at the bill signing can be another way for her grandson to feel proud of his mother.

“(The board) will allow for my daughter and those who have already lost their lives to domestic violence … to no longer be just a number,” Gandy said. “They will be a number with a purpose.”

Family members at the April 15 private bill signing included Ashla Hudson, whose son Collins, died last year in Jackson. Grandparents Mary and Charles Reed and brother Colby Kernell attended the event in honor of Bailey Mae Reed, who died in Oxford in 2023.

Joining them were staff and board members from the Mississippi Coalition Against Domestic Violence, the statewide group that supports shelters and advocated for the passage of Senate Bill 2886 to form a Domestic Violence Facility Review Board.

The law will go into effect July 1, and the coalition hopes to partner with elected officials who will make recommendations for members to serve on the board. The coalition wants to see appointees who have frontline experience with domestic violence survivors, said Luis Montgomery, public policy specialist for the coalition.

A spokesperson from Gov. Tate Reeves’ office did not respond to a request for comment Friday.

Establishment of the board would make Mississippi the 45th state to review domestic violence fatalities.

Montgomery has worked on passing a review board bill since December 2023. After an unsuccessful effort in 2024, the coalition worked to build support and educate people about the need for such a board.

In the recent legislative session, there were House and Senate versions of the bill that unanimously passed their respective chambers. Authors of the bills are from both political parties.

The review board is tasked with reviewing a variety of documents to learn about the lead up and circumstances in which people died in domestic violence-related fatalities, near fatalities and suicides – records that can include police records, court documents, medical records and more.

From each review, trends will emerge and that information can be used for the board to make recommendations to lawmakers about how to prevent domestic violence deaths.

“This is coming at a really great time because we can really get proactive,” Montgomery said.

Without a board and data collection, advocates say it is difficult to know how many people have died or been injured in domestic-violence related incidents.

A Mississippi Today analysis found at least 300 people, including victims, abusers and collateral victims, died from domestic violence between 2020 and 2024. That analysis came from reviewing local news stories, the Gun Violence Archive, the National Gun Violence Memorial, law enforcement reports and court documents.

Some recent cases the board could review are the deaths of Collins, Napier and Reed.

In court records, prosecutors wrote that Napier, 24, faced increased violence after ending a relationship with Chance Fabian Jones. She took action, including purchasing a firearm and filing for a protective order against Jones.

Jones’s trial is set for May 12 in Wayne County. His indictment for capital murder came on the first anniversary of her death, according to court records.

Collins, 25, worked as a nurse and was from Yazoo City. His ex-boyfriend Marcus Johnson has been indicted for capital murder and shooting into Collins’ apartment. Family members say Collins had filed several restraining orders against Johnson.

Johnson was denied bond and remains in jail. His trial is scheduled for July 28 in Hinds County.

He was a Jackson police officer for eight months in 2013. Johnson was separated from the department pending disciplinary action leading up to immediate termination, but he resigned before he was fired, Jackson police confirmed to local media.

Reed, 21, was born and raised in Michigan and moved to Water Valley to live with her grandparents and help care for her cousin, according to her obituary.

Kylan Jacques Phillips was charged with first degree murder for beating Reed, according to court records. In February, the court ordered him to undergo a mental evaluation to determine if he is competent to stand trial, according to court documents.

At the bill signing, Gandy said it was bittersweet and an honor to meet the families of other domestic violence homicide victims.

“We were there knowing we are not alone, we can travel this road together and hopefully find ways to prevent and bring more awareness about domestic violence,” she said.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days agoJim talks with Rep. Robert Andrade about his investigation into the Hope Florida Foundation

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoPrayer Vigil Held for Ronald Dumas Jr., Family Continues to Pray for His Return | April 21, 2025 | N

-

Mississippi Today5 days ago

Mississippi Today5 days ago‘Trainwreck on the horizon’: The costly pains of Mississippi’s small water and sewer systems

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days agoMeteorologist Chita Craft is tracking a Severe Thunderstorm Warning that's in effect now

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed4 days agoTrump touts manufacturing while undercutting state efforts to help factories

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days agoNo. 3 Texas walks off No. 9 LSU again to capture crucial SEC softball series

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed4 days agoFederal report due on Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina’s path to recognition as a tribal nation

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days agoAs country grows more polarized, America needs unity, the ‘Oklahoma Standard,’ Bill Clinton says