News from the South - Louisiana News Feed

‘They lied to us from the beginning’: Deported Louisiana family says ICE lured them with ruse

‘They lied to us from the beginning’: Deported Louisiana family says ICE lured them with ruse

by Bobbi-Jean Misick, Verite, Louisiana Illuminator

March 14, 2025

Stephanie Ali did not think she and her family were being deported to Honduras in late January, until they reached their gate inside a Houston airport.

Earlier that day, she, her mother Claudia Hernandez and younger brother Jason met with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents near their home in Metairie, where they were told they were going to Houston for a hearing in immigration court, Stephanie said.

But instead of escorting them out of the airport when they deplaned in Houston, agents walked them to another gate, according to Stephanie. The flight display said “McAllen” – a Texas city close to the Mexican border.

“I was so scared,” Stephanie said in a phone interview with Verite News from her aunt’s home in San Pedro Sula, a city in northwestern Honduras. “Even just to think of it right now, I start to cry because it’s so horrible.”

She said ICE agents in Louisiana had assured her family that they were not under arrest and weren’t being deported.

But by the following day, they were back in Honduras — the country where Stephanie was born, but barely remembered. By the time the ICE agents returned her there in January, the family had been living in the United States since she was 10, 14 years earlier.

Jason, who was three when the family came to the United States, couldn’t remember Honduras at all.

Soon after they flew into the country, the Alis’ travel visas expired. The family, however, remained.

For years they sought a legal way to stay in the U.S, applying for asylum on the basis that they’d been targeted by gangs. The claim was denied.

“New Orleans was home for us, and they literally just took it away from us like they didn’t care about us,” Stephanie said.

Days before the family’s abrupt removal from the country, Donald Trump was inaugurated for his second term as U.S. president. As a candidate, Trump promised to take an extremely hard line on immigration — enhanced border security, vastly expanded use of immigration detention and mass deportations of undocumented immigrants.

On his first day in office, Trump signed a series of executive actions related to immigration, including one that expanded the “expedited removal” process, making it easier to quickly deport undocumented immigrants. After Trump’s election, immigrant activists in the New Orleans metro area warned communities to brace for increased encounters with ICE.

The Ali family had been on ICE’s radar, facing removal, for some time. They had a pending application for a temporary reprieve from deportation when, in mid-January, a case manager working for an ICE contractor asked them for a meeting at a nearby office, promising “good news.”

For months the family had been monitored through one of ICE’s “alternatives to detention” programs, which use various technologies to track immigrants who are not detained and pose little or no security threat. The case manager said the family didn’t need to be under surveillance anymore.

When they arrived ICE agents were waiting for them. Less than 36 hours later, they were in Honduras.

While deceptive, such “ruses,” as they are referred to in internal agency memos and operational manuals are neither illegal nor new. But some immigrants’ rights advocates said they are concerned that agents will increase their use of ruses under Trump, creating chaos in immigrant communities.

“There’s a huge human cost,” said Jeremy Jong, an attorney at immigrant support organization Al Otro Lado. “Let’s say a single parent gets tricked and detained and they don’t have any time to make sure people are responsible for their kids. What happens to their kids?”

ICE did not respond to multiple requests from Verite News for interviews, answers to questions about methods used to arrest immigrants and about the events surrounding the Ali family’s deportation.

Attorneys for the family, at Mayeaux and Associates in Baton Rouge, declined an interview request but confirmed Stephanie’s timeline of the events leading up to the Jan. 29 deportation.

‘Y’all lied to us’

Members of the Ali family had been facing removal since 2018, when they were denied an asylum claim that would have allowed them to remain in the country legally. They were then placed under a removal order.

In 2023 the family applied for a temporary stay on deportation. But that application was still in process when, in October of last year, they were placed in the surveillance program, which required them to be tracked through a GPS monitoring app on their phones and to meet periodically in person with a case manager.

Hernandez, Stephanie’s mother, said she was nervous when they were first placed under supervision. The immigrants she knew in the program had only recently arrived in the U.S.

The Ali family had been in the country for more than a decade, moving here to escape gang violence, according to filings in the family’s immigration case, which were reviewed by Verite News.

Those filings also show that in Honduras, Julio, who worked as an accountant, had become a target for extortion simply because gang members assumed he had money.

“My husband and I decided to flee for this reason, because we did not want to be killed by the gangs,” Hernandez said in a sworn statement from 2023.

The Alis arrived in the United States in 2011. Here, Claudia said, she finally felt safe.

“You could be free to do your things, be yourself and you don’t have to hide anything,” she said, speaking Spanish while Stephanie translated.

The family made a life in the New Orleans area, settling in Metairie. Julio worked in construction until his death in 2022. Hernandez said she worked as a cleaner on construction sites when the family first arrived, but switched to cleaning houses because the schedule allowed her to be home when her kids returned from school.

The children grew accustomed to American life. Jason said he only realized his family was undocumented as an adolescent.

Stephanie, now 24, had received a life-saving open heart surgery at Children’s Hospital in New Orleans when she was 11 and later attended Grace King High School in Metairie.

The family asked for the stay of removal on the basis of Stephanie’s still-delicate heart condition.

Their request was still pending in mid-January, when Stephanie and Claudia were contacted by the surveillance case manager with “good news.”

The meeting was to be held at an office in St. Rose — about a 20-minute drive from the family’s Metairie house — used by the federal contractor that manages the surveillance program. When the family arrived, they were ushered into a room with ICE agents, Stephanie said. She said one agent – a woman – said the family needed to attend a court hearing in Houston that day for an immigration judge to decide whether they would remain in the U.S. or not.

“I started to worry,” Stephanie said. “I was like, ‘This is not what we’re here for. Y’all lied to us.’”

Stephanie said the agent assured her and her family that they were not being deported and that they were not under arrest. Still, according to Stephanie, the agents did not let them leave the office and told them they could not call their immigration attorney until they got to the Houston court.

Although New Orleans has its own immigration court, agents told the Alis that they would get a hearing faster in Houston, where there are three immigration courts, Stephanie said.

The agents took away their electronics, their jewelry and even their hair ties, Stephanie said. Before agents took her phone and turned it off, she managed to send some messages in Spanish to a friend in New Orleans, Melisa Escobar.

“I don’t know if we will return or if we will get deported,” Stephanie wrote on WhatsApp.

She wrote: “Give a kiss to Lili,” referring to Escobar’s three year old daughter. Then Stephanie stopped writing.

Agents had the family mark a couple of documents with their fingerprints, barely allowing a chance to read them, Stephanie said.

Stephanie said agents told her they would provide her with medication for her heart condition once they arrived in court in Houston, then placed the family into a van on its way to Louis Armstrong International Airport.

Three agents accompanied them on a flight from New Orleans to Houston, telling the family not to worry because “everything would be OK,” Stephanie said, adding that the agents told her they had already booked her family a flight back to New Orleans after the hearing was over. But once they arrived in Houston, she said, the agents escorted them to another gate in the airport terminal to wait for a connecting flight to McAllen.

“Are we not coming back to New Orleans?” Stephanie said she asked the agents. “What’s going on?” But they were no longer talking to her.

After arriving in McAllen, Stephanie said the family was taken to a hotel for the night. There, she said, an ICE agent visited their room and confirmed that they were being sent back to Honduras.

“They lied to us from the beginning,” Stephanie said. “What they did was wrong.”

She said the agent provided her with a 60-day supply of her medication. When she asked what would happen once it ran out, the agent indicated she’d be on her own, Stephanie said.

New Orleans was home for us, and they literally just took it away from us like they didn’t care about us.

– Stephanie Ali

“I was devastated,” Stephanie said. “It’s heartbreaking for a country that you see as home treating you this way.”

The next day Stephanie, her mother and brother were put on a plane to San Pedro Sula, where, she said, they were finally given back their belongings and called their attorney in Louisiana.

According to Stephanie, the family’s attorneys said there was nothing the family could do to change their situation, now that they were in Honduras. They would likely be banned from entering the U.S. for years as a penalty.

Stephanie called Escobar to tell her what had happened. And then, in a message, she assured her friend that she’d be OK, even if she didn’t quite believe it herself.

“No te preocupes mi mely.” Don’t worry, my Mely, she said. “Todo estará bien.” Everything will be fine.

‘They’re leaning into the tricks’

Although Stephanie and her family felt blindsided by ICE’s tactics, the deceptive methods that they say ICE agents used to deport them are not only legal, but also have also been encouraged for years.

A 2005 Department of Homeland Security memo provided guidance on the use of ruses in immigration, reminding agents at one point that if their ruses involve “adopt[ing] the guise of a different agency,” a supervisor should inform that agency of the deception. A 2010 fugitive operations handbook for ICE’s enforcement and removal operations department details how ruses are “designed to control the time and location of a law enforcement encounter.”

The agency’s use of ruses reportedly increased under the first Trump administration. And in the early months of Trump’s second term, Jong, from Al Otro Lado, said he and other immigrants rights advocates have noticed an increase in incidents of agents using deception to arrest, detain and deport immigrants.

“It’s everywhere,” Jong said. “We’ve been hearing from people across the country that they’re using tricks to get people to come in and get arrested.”

Last month, the Gulf States Newsroom reported on a separate case of an unnamed migrant under ICE supervision in Louisiana who received a text message saying they were being placed on a reduced level of surveillance, only to be arrested at an in-person meeting. And in Florida, a Venezuelan man under supervision was arrested at a routine check-in, according to a report from NBC News.

Jong said he and fellow immigrants’ rights advocates have seen a range of ruses used on their clients. Immigrants’ rights advocates have argued that ruses — especially in order to enter a subject’s home to conduct a warrantless search — can violate Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures.

“They almost never have a warrant,” Jong said. “ICE really relies on people giving themselves up and that’s why they’re leaning into the tricks.”

‘It’s just so humiliating’

Stephanie said she “never imagined” her family would be deported. She said she feels cut off from the community she’s known since she was a child. Her friends, her doctors and her father’s grave are back in the U.S.

As bad as it is for her, she said feels worse for those who have not yet been ensnared by the federal immigration system but soon may be.

“People think that [they] are criminals, because they arrest them. They handcuffed their hands and their feet and everything,” Stephanie said. “To my Latino people, looking at them like that, it’s just so humiliating.”

Enrollment in one of ICE’s supervision programs does not shield anyone from deportation.

Jong said he fears that Trump’s second term will bring increased data sharing between government agencies, which could allow ICE to target undocumented immigrants under surveillance who are applying for legal ways to stay in the U.S.

“Whenever there’s a Trump administration, there’s always this idea of, ‘If you apply for something, we can use that information against you,’” Jong said.

The new Trump administration, meanwhile, appears undeterred in making good on the president’s pledge to carry out “the most sweeping border and immigration crackdown in American history.”

According to an NBC News report last week, the feds are gearing up for an operation targeting undocumented families with minor children, like the Alis. Stephanie said she worries for others who may meet the same fate as her family.

“It’s just something that I wish nobody could go through,” she said.

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

This article first appeared on Verite News New Orleans and is republished here under a Creative Commons license. PARSELY = { autotrack: false, onload: function() { PARSELY.beacon.trackPageView({ url: “https://veritenews.org/2025/03/13/deported-family-ice-deception-immigration/”, urlref: window.location.href }); } }

Louisiana Illuminator is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Louisiana Illuminator maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Greg LaRose for questions: info@lailluminator.com.

The post ‘They lied to us from the beginning’: Deported Louisiana family says ICE lured them with ruse appeared first on lailluminator.com

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed

One state framed wetlands as a flooding solution. Could it work elsewhere?

by Madeline Heim and Caitlin Looby, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Louisiana Illuminator

April 19, 2025

ASHLAND, Wis. — In less than 10 years, three catastrophic floods ravaged northwestern Wisconsin and changed the way people think about water.

The most severe, in July 2016, slammed Ashland with up to 10 inches of rain in less than a day — a month’s worth of rain fell in just two hours. As rivers swelled to record highs, major highways broke into pieces and culverts washed away. It took months for roads to reopen, with more than $41 million in damage across seven counties.

The Marengo River, which winds through forests and farmland before meeting the Bad River that flows into Lake Superior, was hit hard during these historic deluges. Centuries earlier, the upper watershed would have held onto that water, but logging and agriculture left the river disconnected from its floodplain, giving the water nowhere safe to go.

Today, the Marengo River stands as an example of a new kind of solution. Following the record floods, state leaders invested in opening up floodplains and restoring wetlands to relieve flooding. As the need to adapt to disasters grows more urgent, the Marengo River serves as an example that there’s a cheaper way to do so: using wetlands.

“We can’t change the weather or the patterns… but we can better prepare ourselves,” said MaryJo Gingras, Ashland County’s conservationist.

Wetlands once provided more natural flood storage across Wisconsin and the Mississippi River Basin, soaking up water like sponges so it couldn’t rush further downstream. But about half of the country’s wetlands have been drained and filled for agriculture and development, and they continue to be destroyed, even as climate change intensifies floods.

As the federal government disposes of rules to protect wetlands, environmental advocates want to rewrite the ecosystem’s narrative to convince more people that restoration is worth it.

Wetlands aren’t just pretty places, advocates argue, but also powerhouses that can save communities money by blunting the impact of flood disasters. A 2024 Wisconsin law geared at preventing such disasters before they happen, inspired by the wetland work in the Marengo River watershed, is going to test that theory.

“Traditionally, the outreach has been, ‘We want to have wetlands out here because they’re good for ducks, frogs and pretty flowers,’” said Tracy Hames, executive director of the Wisconsin Wetlands Association. “What do people care about here? They care about their roads, their bridges, their culverts … how can wetlands help that?”

Bipartisan bill posed wetlands as flood solution

Northern Wisconsin isn’t the only place paying the price for floods. Between 1980 and 2025, the U.S. was struck by 45 billion-dollar flood disasters, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, with a cumulative price tag of nearly $206 billion. Many parts of the vast Mississippi River Basin receive up to eight inches more rain annually than they did 50 years ago, according to a 2022 analysis from Climate Central, a nonprofit organization that analyzes climate science.

Damaging floods are now so common in the states that border the Mississippi River, including Wisconsin, that the issue can’t be ignored, said Haley Gentry, assistant director of the Tulane Institute on Water Resources Law and Policy in New Orleans.

“Even if you don’t agree with certain (regulations) … we absolutely have to find ways to reduce damage,” Gentry said.

Former Wisconsin state Rep. Loren Oldenburg, a Republican who served a flood-prone district in southwest Wisconsin until he lost the seat last year, was interested in how wetlands could help.

Oldenburg joined forces with Republican state Sen. Romaine Quinn, who represents northern Wisconsin and knew of the work in the Marengo River watershed. The lawmakers proposed a grant program for flood-stricken communities to better understand why and where they flood and restore wetlands in areas that need the help most.

Jennifer Western Hauser, policy liaison at the Wisconsin Wetlands Association, met with Democratic and Republican lawmakers to advocate for the bill. She emphasized problems that might get their attention — related to transportation, emergency services, insurance, or conservation — that wetland restoration could solve. She said she got a lot of head-nods as she explained that the cost of continually fixing a washed-out culvert could vanish from storing and slowing floodwaters upstream.

“These are issues that hit all over,” she said. “It’s a relatable problem.”

(MaryJo Gingras/Ashland County Land & Water Conservation Dept.)

The bill passed unanimously and was signed into law by Democratic Gov. Tony Evers in April 2024. Evers and the Republican-controlled Legislature approved $2 million for the program in the state’s most recent budget.

Twenty-three communities applied for the first round of grant funding, which offered two types of grants — one to help assess flood risk, and another grant to help build new wetlands to reduce that risk. Eleven communities were funded, touching most corners of the state, according to Wisconsin Emergency Management, which administered the grants.

Brian Vigue, freshwater policy director for Audubon Great Lakes, said the program shows Wisconsinites have come a long way in how they think about wetlands since 2018, when the state government made it easier for developers to build in them.

There’s an assumption that wetland restoration comes only at the expense of historically lucrative land uses like agriculture or industry, making it hard to gain ground, Vigue said. But when skeptics understand the possible economic benefits, it can change things.

“When you actually find something with the return on investment and can prove that it’s providing these benefits … we were surprised at how readily people that you’d assume wouldn’t embrace a really good, proactive wetland conservation policy, did,” he said.

Private landowners need to see results

About three-quarters of the remaining wetlands in the lower 48 states are on privately owned land, including areas that were targeted for restoration in the Marengo River watershed. That means before any restoration work begins, the landowner must be convinced that the work will help, not hurt them.

For projects like this to work, landowner goals are a priority, said Kyle Magyera, local government outreach specialist at the Wisconsin Wetlands Association, because “they know their property better than anyone else.”

Farmers, for example, can be leery that beefing up wetlands will take land out of production and hurt their bottom line, Magyera said.

In the Marengo watershed, Gingras worked with one landowner who had farmland that wasn’t being used. They created five new wetlands across 10 acres that have already decreased sediment and phosphorus runoff from entering the river. And while there hasn’t been a flood event yet, Gingras expects the water flows to be slowed substantially.

This work goes beyond restoring wetland habitat, Magyera said, it’s about reconnecting waterways. In another project, Magyera worked on a private property where floods carved a new channel in a ravine that funneled the water faster downstream. The property now has log structures that mimic beaver dams to help slow water down and reconnect these systems.

(Mark Hoffman/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

Now that the first round of funding has been disbursed in Wisconsin’s grant program, grantees across the state are starting work on their own versions of natural flood control, like that used in Marengo.

In Emilie Park, along the flood-prone East River in Green Bay, a project funded by the program will create 11 acres of new wetlands. That habitat will help store water and serve as an eco-park where community members can stroll through the wetland on boardwalks.

In rural Dane County, about 20 miles from the state capital, a stretch of Black Earth Creek will be reconnected to its floodplain, restoring five and a half acres of wetlands and giving the creek more room to spread out and reduce flood risk. The creek jumped its banks during a near record-breaking 2018 rainstorm, washing out two bridges and causing millions of dollars in damage.

Voluntary program could be of interest elsewhere

Nature-based solutions to flooding have been gaining popularity along the Mississippi River. Wisconsin’s program could serve as a “national model” for how to use wetlands to promote natural flood resilience, Quinn wrote in a 2023 newspaper editorial supporting the bill.

Kyle Rorah, regional director of public policy for the Great Lakes/Atlantic region of Ducks Unlimited, said he’s talking about the Wisconsin grant program to lawmakers in other states in the upper Midwest, and that he sees more appetite for this model than relying on the federal government to protect wetlands.

And Vigue has found that stakeholders in industries like fishing, shipping and recreation are receptive to using wetlands as infrastructure.

But Gentry cautioned that voluntary restoration can only go so far, because it “still allows status-quo development and other related patterns to continue.”

Still, as the federal government backs off of regulation, Gentry said she expects more emphasis on the economic value of wetlands to drive protection.

Some of that is already happening. A 2024 analysis from the Union of Concerned Scientists found that wetlands save Wisconsin and the upper Midwest nearly $23 billion a year that otherwise would be spent combating flooding.

“Every level of government is looking at ways to reduce costs so it doesn’t increase taxes for their constituents,” Gingras said.

John Sabo, director of the ByWater Institute at Tulane University, said as wetlands prove their economic value in reducing flood damage costs, taxpayers will see their value.

“You have to think about (wetlands) as providing services for people,” Sabo said, “if you want to get people on the other side of the aisle behind the idea (of restoring them).”

And although the Wisconsin grant program is small-scale for now, he said if other states bordering the Mississippi River follow its lead, it could reduce flooding across the region.

“If all upstream states start to build upstream wetlands,” he said, “that has downstream impacts.”

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

Louisiana Illuminator is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Louisiana Illuminator maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Greg LaRose for questions: info@lailluminator.com.

The post One state framed wetlands as a flooding solution. Could it work elsewhere? appeared first on lailluminator.com

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed

Easter Weekend: Muggy, warm, and windy

SUMMARY: Easter Weekend will be warm, muggy, and breezy, with mostly cloudy skies and temperatures in the low 80s. Current conditions are in the low 70s, making it a sticky day for events like the Crescent City Classic. While there’s a slight chance of rain on Sunday, most of the day will remain dry. Winds from the southeast could gust near 30 mph. Next week, a front will bring increased rain chances and storms starting Monday, with unsettled conditions continuing into Tuesday and Wednesday. Despite this, warm temperatures in the 80s will persist throughout the week.

Easter Weekend looks very nice! It will be hot, humid, and windy with high temperatures in the lower 80s both afternoons. More clouds will be around with some breaks

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed

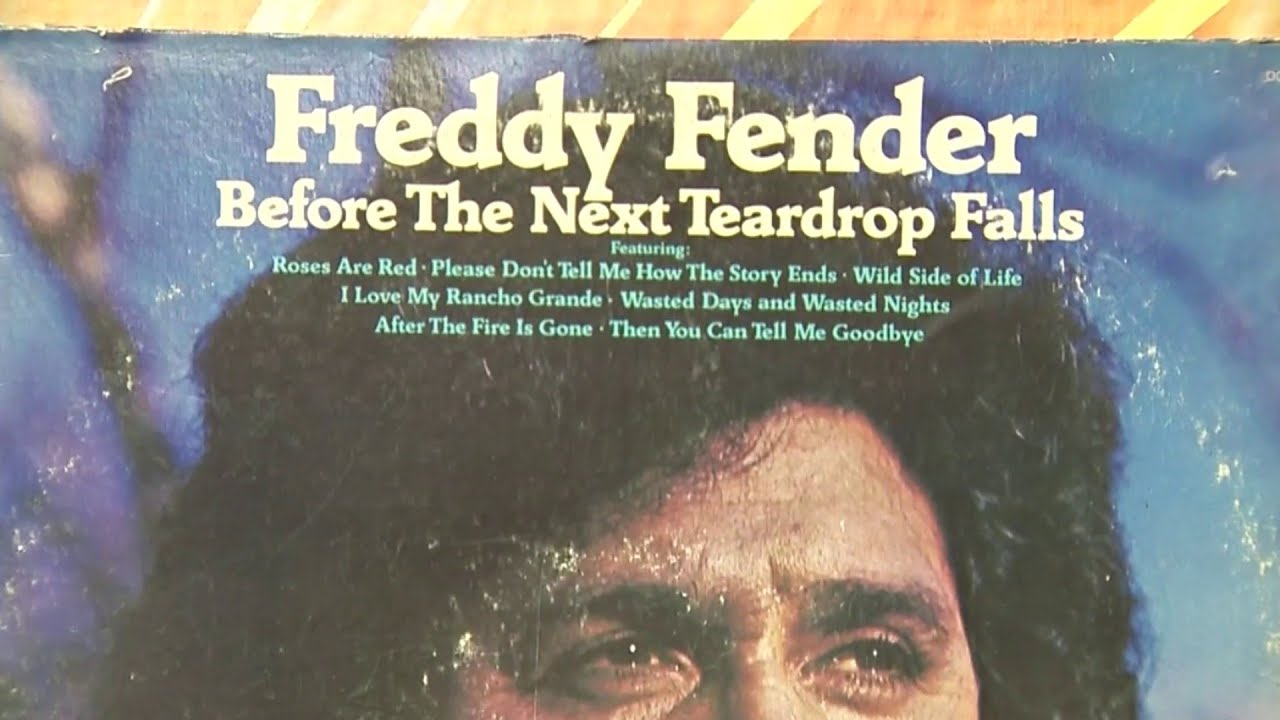

Vicente Fernandez and Freddy Fender join National Recording Registry

SUMMARY: This year, Vicente Fernandez’s “El Rey” and Freddy Fender’s “Before the Next Teardrop Falls” were inducted into the National Recording Registry, alongside Lin-Manuel Miranda’s *Hamilton* album. Congressman Joaquin Castro has championed the inclusion of more Latino artists in the registry, noting that Latino representation is only 5%. Over the last three years, with input from constituents, Castro has successfully nominated 30 songs and albums, including iconic Latino tracks. He advocates for more Latino contributions to be recognized, including Selena’s work. Castro will continue gathering nominations for 2026, aiming to better reflect Latino cultural influence in the registry.

Each year since 2000, the Library of Congress has selected influential songs and albums to be preserved in the National Recording Registry. This year, three Latino artists were inducted — two of them with deep roots in Latino culture and South Texas.

-

Mississippi Today7 days ago

Mississippi Today7 days agoLawmakers used to fail passing a budget over policy disagreement. This year, they failed over childish bickering.

-

Mississippi Today7 days ago

Mississippi Today7 days agoOn this day in 1873, La. courthouse scene of racial carnage

-

Local News7 days ago

Local News7 days agoSouthern Miss Professor Inducted into U.S. Hydrographer Hall of Fame

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoFoley man wins Race to the Finish as Kyle Larson gets first win of 2025 Xfinity Series at Bristol

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoFederal appeals court upholds ruling against Alabama panhandling laws

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoJacksonville University only school with 2 finalist teams in NASA’s 2025 Human Lander Challenge

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days agoInsects as food? ‘We are largely ignoring the largest group of organisms on earth’

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days ago1 dead after 7 people shot during large gathering at Crosby gas station, HCSO says