Mississippi Today

These states are using fetal personhood to put women behind bars

This article was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system, AL.com, The Frontier, The Post and Courier and The Guardian. Sign up for The Marshall Project’s newsletters, and follow them on Instagram, TikTok, Reddit and Facebook.

When Quitney Armstead learned she was pregnant while locked up in a rural Alabama jail, she made a promise — to God and herself — to stay clean.

She had struggled with addiction and post-traumatic stress disorder for nearly a decade, since serving in the Iraq War. But when she found out she was pregnant with her third child, in October 2018, she resolved: “I want to be a mama to my kids again.”

Armstead says she did stay clean before delivering a baby girl in January 2019. Records show that hospital staff performed initial drug tests, and Armstead was negative.

Armstead didn’t know that Decatur Morgan Hospital also sent her newborn’s meconium — the baby’s first bowel movement — to the Minnesota-based Mayo Clinic for more advanced testing. Those test results showed traces of methamphetamine — drugs Armstead says she took before she knew she was pregnant. Because meconium remains in the fetus throughout pregnancy, it can show residue of substances from many months before that are no longer in the mother’s system.

Child welfare workers barred Armstead from seeing her daughter, Aziyah, while they investigated, and Armstead’s mother stepped in to care for the newborn.

The hospital shared the meconium test results with local police, who then combed through months of medical records for Armstead and her baby to build a criminal case. Prosecutors alleged that the drugs she had taken much earlier in the pregnancy could have put the fetus at risk. Nearly a year after she’d delivered a healthy baby, Armstead was arrested and charged with chemical endangerment of a child.

She is one of hundreds of women prosecuted on similar charges in Alabama, Mississippi, Oklahoma and South Carolina. Law enforcement and prosecutors in those states have expanded their use of child abuse and neglect laws in recent years to police the conduct of pregnant women under the concept of “fetal personhood,” a tenet promoted by many anti-abortion groups that a fetus should be treated legally the same as a child.

These laws have been used to prosecute women who lose their pregnancies. But prosecutors are also targeting people who give birth and used drugs during their pregnancy. This tactic represents a significant shift toward criminalizing mothers: In most states, if a pregnant woman is suspected of using drugs, the case could be referred to a child welfare agency, but not police or prosecutors.

Medical privacy laws have offered little protection. In many cases, health care providers granted law enforcement access to patients’ information, sometimes without a warrant. These women were prosecuted for child endangerment or neglect even when they delivered healthy babies, an investigation by The Marshall Project, AL.com, The Frontier, The Post & Courier and Mississippi Today found.

In these cases, whether a woman goes to prison often depends on where she lives, what hospital she goes to and how much money she has, our review of records found. Most women charged plead guilty and are separated from their children for months, years — or forever. The evidence and procedures are rarely challenged in court.

Prosecutors who pursue these criminal cases say they’re protecting babies from potential harm and trying to get the mothers help in some cases.

But medical experts warn that prosecuting pregnant people who seek health care could cause them to avoid going to a doctor or hospital altogether, which is dangerous for the mother and the developing fetus. Proper prenatal care and drug treatment should be the goal, they argue — not punishment.

Dr. Tony Scialli, an obstetrician/gynecologist who specializes in reproductive and developmental toxicology, said the prosecutions are an abuse of drug screenings and tests designed to assess the medical needs of the mother and infant. He said that drug use doesn’t necessarily harm a fetus. “Exposure does not equal toxicity,” Scialli said.

But prosecutors in these states aren’t required to prove harm to the fetus or newborn — simply exposure at some point during the pregnancy.

Legal experts say that under this expanded use of child welfare laws, prosecutors could also pursue criminal charges for a pregnant person who drinks wine or uses recreational marijuana — even where it’s legal. Police could also comb through medical records to investigate whether a life-saving abortion was medically necessary or to allege that a miscarriage was actually the result of a self-managed abortion.

Because of concerns about people being criminally punished for seeking reproductive healthcare after last year’s reversal of Roe v. Wade, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is working to strengthen privacy rules under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA.

Scialli said the prosecutions ignore the effects of separating a newborn from a mother, which research has shown harms the child. Several studies have shown that even when newborns exhibit signs of drug withdrawal at birth, keeping them in hospital rooms with their mothers improves their health outcomes.

Just because a person struggles with addiction doesn’t necessarily mean she is an unfit mother, Scialli said. “Even women who are using illicit drugs, they’re usually highly motivated to take care of their children. Unless the mother is being neglectful, separating the baby and mother is not healthy for either of them.”

Armstead grew up Quitney Butler in Town Creek, about two hours northwest of Birmingham. She watched as her town lost its Dairy Queen, grocery store, and eventually even the high school she graduated from in 2006.

She was deployed to Iraq in 2009, the same year her school closed. By then, she was 21 with one young daughter, Eva, with her boyfriend, Derry Armstead.

In Iraq, she drove trucks and made sure fellow soldiers got their mail. She was stationed at Forward Operating Base Hammer, in a stretch of desert east of Baghdad that was often the target of attacks.

Armstead came back from war in 2010 “a completely different person,” said her mother, Teresa Tippett. She was argumentative and temperamental.

Her family members “all said I changed when I went over there,” Armstead recalled. “I was like, ‘Mama, we were getting bombed all day, every day.’”

Armstead came home looking for an escape. She found drugs and trouble.

After her boyfriend returned from his deployment to Afghanistan, they married in 2012 and had a second daughter, Shelby. But their relationship became tumultuous, records show.

Both were arrested after a 2014 fight where he claimed she damaged his property, and she claimed he struck her on the leg, court records show. The following year, police records allege her husband drove his pickup past railroad barricades and into the side of a moving train, with his wife in the passenger seat.

Because of the couple’s fighting and arrests, her mother had custody of both Eva and Shelby. Quitney Armstead picked up two drug possession charges, and a misdemeanor charge for throwing a brick at the car her husband was in. Their divorce was granted in 2018, court records show.

In October 2018, she ended up back in jail after she was arrested on a drug possession charge during a police raid of a relative’s house, according to court records.

That’s when she found out she was pregnant with Aziyah, and promised herself she would get clean.

Not long before Armstead’s legal troubles began, some prosecutors in Alabama started to use a chemical endangerment statute — originally designed to protect children from chemical exposures in home meth labs — to punish women whose drug use potentially exposed their fetuses in the womb.

Prosecutions vary widely from county to county. In some areas, district attorneys choose not to pursue these charges, while one county has charged hundreds of women. In 2016, lawmakers carved out an exemption for exposure to prescription drugs, which can also be harmful to a fetus.

Morgan County District Attorney Scott Anderson said he does not discuss details and facts about pending cases.

“However, I will tell you that my position of being willing to allow mothers charged with chemical endangerment into diversion programs has not changed. I am willing to do that and, if at all possible, I favor that approach in resolving these type cases,” he wrote in an email. “I think that Ms. Armstead needs treatment for drug dependency and am in favor of her getting it.”

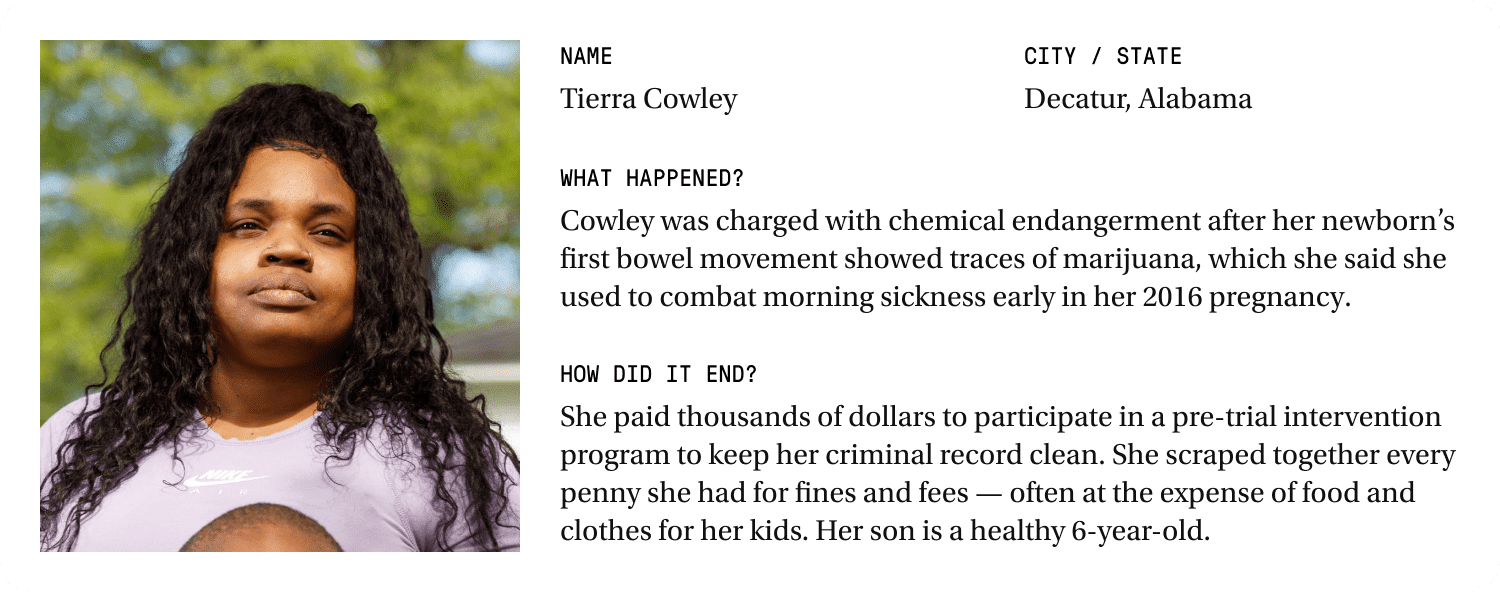

Some Alabama women we interviewed avoided a felony conviction and prison time by participating in pre-trial intervention programs run by prosecutors, which offer some treatment options. In some counties, the cost is $700 just to apply. Participants must keep making payments to remain enrolled. If they can’t afford to keep up, they face an automatic guilty plea.

In his email, Anderson said poverty does not prevent a person from entering diversion programs in his county.

In several Alabama cases, including Armstead’s, the mother and her newborn initially tested negative for drugs — but the hospital sent the baby’s meconium to a lab for more extensive testing.

Armstead said she never granted permission specifically for the test and had no idea her newborn’s meconium was being sent to the Mayo Clinic. A spokesperson for Decatur Morgan Hospital, where Armstead gave birth, wrote in an email statement that the hospital drug tests “all mothers who are admitted to our hospital for labor and delivery. Our hospital follows Alabama law regarding any required reporting of test results to state authorities.”

A federal law requires each state to have a policy on how to report and examine cases of drug-exposed newborns — but the federal statute doesn’t require states to conduct criminal investigations. About half the states stipulate that healthcare providers report to child welfare agencies when a newborn or mother tests positive for drugs, but only a handful pursue criminal prosecutions of the mothers.

Some prosecutors in Alabama, South Carolina and Oklahoma have determined that under those states’ laws and court rulings establishing fetal personhood, child welfare statutes can apply to a fetus. Mississippi doesn’t have a fetal personhood law, but that hasn’t stopped prosecutors in at least two counties from filing criminal charges against women who tested positive for drugs while pregnant.

In northeast Mississippi’s Monroe County, Sheriff’s Investigator Spencer Woods said he spearheaded the effort to begin prosecuting women under the concept of fetal personhood in 2019. Before that, Woods said, when the sheriff’s office received a referral from Child Protection Services about a newborn testing positive for drugs, officers wouldn’t investigate.

“It wouldn’t be handled because it did not fall under the statute. It still does not fall under the statute,” he said. “Because the state of Mississippi does not look at a child as being a child until it draws its first breath. Well, when that child tests positive when it’s born, the abuse has already happened, and it didn’t happen to a ‘child.’ So it was a crack in the system the way I looked at it. And that’s where we’re kind of playing.”

There are several ways law enforcement can learn of alleged drug use. Sometimes, child welfare workers inform police. Occasionally, women themselves admit drug use to an investigator; other times doctors, nurses or hospital staff pass test results to law enforcement or grant officers access to medical records without a warrant.

The cases demonstrate how existing privacy laws don’t protect women’s medical records from scrutiny by law enforcement, said Ji Seon Song, a law professor at the University of California, Irvine, who studies how law enforcement infringe on patients’ privacy.

Child abuse allegations shouldn’t be a “carte blanche to access someone’s private health information, but that’s how it’s being used,” Song said. “When the loyalty to the patient completely disappears, that’s an institutional problem the hospitals need to deal with.”

Because this surveillance system could also be used to police women who seek abortions, federal authorities have proposed a privacy rule addition for HIPAA. Among other changes, it would prohibit disclosure of private health information for criminal, civil or administrative investigations against people seeking lawful reproductive health care. The agency sought public comment on the proposed rule through June 16, and is expected to complete the changes in coming months.

Medical groups supporting the changes argue that using private health information to punish people criminally harms the physician-patient relationship and results in substandard care. But several state attorneys general — including the AGs for Alabama, Mississippi and South Carolina — wrote a statement opposing the change.

As proposed, the HIPAA changes could require law enforcement to provide documentation, such as a search warrant or subpoena, when seeking records related to someone’s reproductive healthcare — and medical providers could still refuse, said Melanie Fontes Rainer, director of the Office for Civil Rights in the Department of Health and Human Services.

“It’s very much real that your information is being used inappropriately sometimes; and then that information is then being used to seek out criminal, civil and administrative prosecution of people,” Fontes Rainer said. “We’re in this new era — of unfortunately targeting populations for the kinds of health care they seek.”

In some cases, women were arrested and prosecuted after being honest with their doctors about their struggles with substance abuse. At one South Carolina hospital, a new mother admitted to occasional drug use while pregnant, only to have hospital staff call police who arrested her after a nurse handed over her medical records.

A few women have even been prosecuted after seeking treatment.

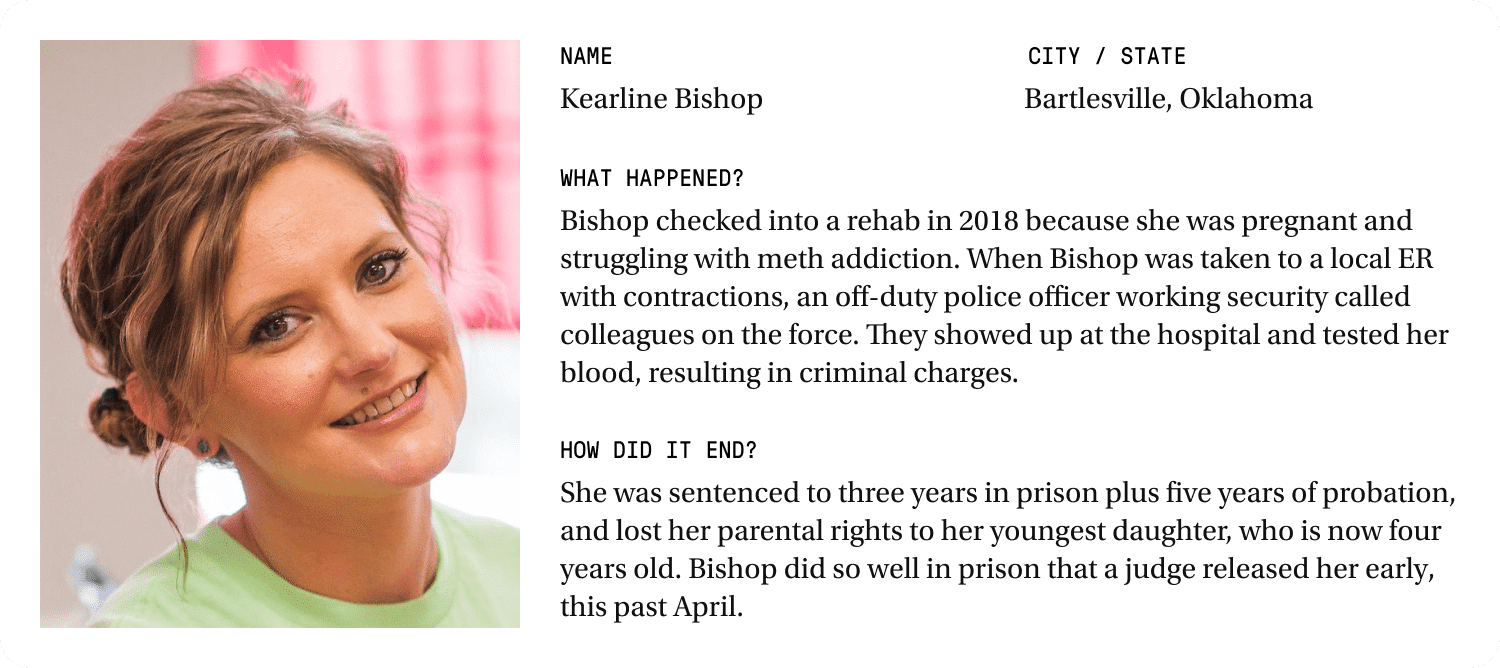

In 2018, Kearline Bishop was pregnant and struggling with meth addiction. She said she checked herself into a rehab program in northeast Oklahoma because she knew she needed help.

When Bishop appeared to have contractions, the rehab transferred her to a local hospital. A doctor at Hillcrest Hospital Claremore determined that she wasn’t yet in labor, and that despite her past drug use, her fetus was healthy.

Then two men Bishop didn’t know walked in. They were police detectives in plain clothes, who demanded a hospital worker draw her blood for testing, according to court records. It turned out that an off-duty police officer working security at the hospital had called his police department supervisor because he’d heard that a pregnant woman admitted to drug use.

The detectives didn’t have a search warrant, so they handed Bishop a “Consent to Search” property form with blank spaces on it. The officers crossed out the line where they would normally list the property to be searched and instead simply wrote “Blood Draw.” Police testified later in court that they didn’t advise Bishop she could talk to a lawyer first.

Bishop had told the cops she “was in a dark place, and needed help,” according to an affidavit.

The blood tests showed traces of drugs in her system. Officers handcuffed Bishop and took her from the hospital to jail. She stayed there until right before she delivered her baby, when she was allowed to go to a treatment house for pregnant women for a few days. When Bishop’s daughter was born, she was healthy. But child welfare workers took her from Bishop the next day.

The District Attorney in Rogers County, northeast of Tulsa, charged Bishop with child neglect. After an initial hearing, a county judge dismissed the charge, ruling the state couldn’t apply its child welfare codes to a fetus.

But the district attorney appealed. Then a 2020 decision in a separate case by the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals ruled that the state’s child neglect law could be applied to fetuses — even ones that didn’t display harm from drug use. The court later ruled that the prosecutor could continue the case against Bishop.

District Attorney Matt Ballard celebrated on Twitter: “My office scored a big victory today fighting for unborn children. I’m proud of all the work that went into this. #ProtectingUnbornChildren”

Through a spokeswoman, Ballard declined an interview request.

Bishop ultimately opted for a blind plea — a form of guilty plea that leaves the sentence entirely up to a judge — in January 2022. She was sentenced to three years in prison, plus five years of probation. A court terminated her parental rights to her youngest daughter.

Bishop did so well in prison that a judge reviewed her case and agreed to her release this past March, after just one year. Her daughter is now a healthy 4-year-old, adopted by a family member. Bishop has no contact with her youngest but saves up the money she makes working to buy clothes to send to her daughter.

Part of Bishop’s motivation to secure an early release, she said, was to prove that the prosecutors and judge who sent her to prison were wrong about her. She said that they never gave her a chance to show she’d be a caring mother.

“They looked at me like I wasn’t even human,” she said.

The cloud of cigarette smoke in Kevin Teague’s Decatur law office is almost as thick as his north Alabama accent. Teague is Armstead’s court-appointed lawyer. He defends a number of women in Morgan County charged with chemical endangerment of a child.

Many of his clients — like most of the women charged in Alabama and other states — reach plea deals, rarely challenging the cases against them. Teague said he had intended to help Armstead plead guilty too, but something about her case gnawed at him.

“She’s just had a hell of a life. I mean, she fought for her country,” he said. “I truly believe she has some serious PTSD.”

Her country — and the state of Alabama — owed her something better, he said. It seems unfair that poor people who can’t afford pre-trial diversion programs get felony convictions and prison time, while people who could afford thousands of dollars in fees can get different outcomes, Teague said.

Armstead missed an October 2022 court hearing — she said she didn’t receive a notice or have transportation. The absence landed her back in jail in December, and, lacking the money for bail, she’s remained behind bars since.

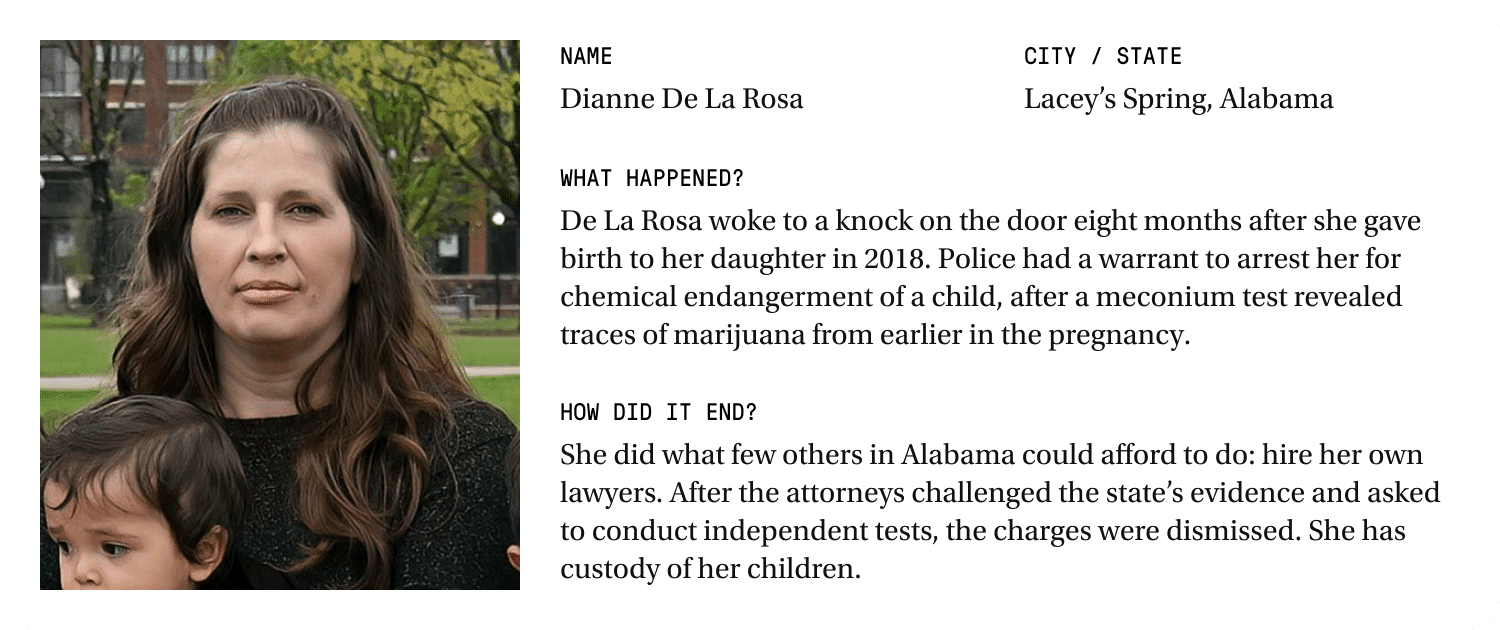

Meanwhile, Teague heard about a chemical endangerment case similar to Armstead’s in which the defendant challenged the evidence and the charges were dismissed: Dianne De La Rosa.

Eight months after De La Rosa’s daughter was born in 2018 in Huntsville, she and her family woke to a knock at the door at 2 a.m. The police had a warrant for her arrest for chemical endangerment. A meconium test allegedly showed traces of marijuana from earlier in the pregnancy.

De La Rosa did something that many women in Morgan County couldn’t afford. She scraped together thousands of dollars to hire her own attorney — John Brinkley.

Brinkley is a father of nine, with another on the way. He had waited in many delivery rooms over the years, and he remembered a key detail: The hospital doesn’t preserve everything it collects when a baby is born.

So Brinkley and his law partner Justin Nance did something unusual: They asked to conduct their own independent drug tests of the meconium in De La Rosa’s case. Defendants in Alabama have the right to request independent testing of evidence. But since so many women plead guilty, it rarely happens.

“It’s unclear the criteria they have for when they do these tests,” Nance said. “They claim they’re doing them on everybody, but I don’t think that is true.”

Prosecutors admitted that the evidence wasn’t preserved, and the charges against De La Rosa were dismissed. That took nearly three years.

Many women charged with chemical endangerment in Alabama can’t afford their own lawyer to fight a criminal case for years, Brinkley said. “They pick on these less fortunate women, and then they just railroad them.”

After hearing about De La Rosa’s case, Teague filed a motion in late March to have the meconium evidence in Armstead’s case independently tested. Prosecutors never responded in a written filing, nor they did not turn over the sample within 14 days, as the court had ordered, Teague said. Armstead’s trial was set for August.

When Teague told Armstead about filing that motion — in hopes of getting her case dismissed — she broke down sobbing.

Teague reminded her it would be a long road, and she would need to work on her sobriety and fulfill the requirements for a veterans’ court program she was offered for a synthetic marijuana possession charge in a nearby county. But it was a glimmer of hope she could hold on to.

“I am not the mistakes I’ve made,” Armstead said. “My kids were my world.”

Her incarceration has isolated her from family. Her jail doesn’t allow in-person visits from anyone but her lawyer, and she barely has the funds to make phone calls.

Her daughter Aziyah is 4 years old now. She and her older sisters only see Armstead on occasional video calls from the county jail, when the family can afford to put money in her jail account.

Armstead recalled that during a recent video chat, Aziyah asked her: “Mommy, can you just sneak out of jail for one night?”

She explained to Aziyah that if she did, she would be there even longer.

“It tore me up,” Armstead said.

Last week, Teague visited her at the jail with news: Morgan County was now offering her a better plea deal. If she successfully completes veterans’ court in nearby Lauderdale County, both her drug possession charge and chemical endangerment charge will be dismissed, he told her. There would be no conviction for either felony, as long as she didn’t screw up.

Armstead knew this meant the state probably didn’t have the meconium evidence. But taking the plea deal meant getting out of jail sooner and hugging her girls. Maybe she would be home in time for back-to-school.

She couldn’t afford to say no.

Additional reporting contributed by Anna Wolfe, Mississippi Today; Amy Yurkanin, AL.com; Brianna Bailey, The Frontier; and Jocelyn Grzeszczak, The Post and Courier.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Mississippi River flooding Vicksburg, expected to crest on Monday

Warren County Emergency Management Director John Elfer said Friday floodwaters from the Mississippi River, which have reached homes in and around Vicksburg, will likely persist until early May. Elfer estimated there areabout 15 to 20 roads underwater in the area.

“We’re about half a foot (on the river gauge) from a major flood,” he said. “But we don’t think it’s going to be like in 2011, so we can kind of manage this.”

The National Weather projects the river to crest at 49.5 feet on Monday, making it the highest peak at the Vicksburg gauge since 2020. Elfer said some residents in north Vicksburg — including at the Ford Subdivision as well as near Chickasaw Road and Hutson Street — are having to take boats to get home, adding that those who live on the unprotected side of the levee are generally prepared for flooding.

“There are a few (inundated homes), but we’ve mitigated a lot of them,” he said. “Some of the structures have been torn down or raised. There are a few people that still live on the wet side of the levee, but they kind of know what to expect. So we’re not too concerned with that.”

The river first reached flood stage in the city — 43 feet — on April 14. State officials closed Highway 465, which connects the Eagle Lake community just north of Vicksburg to Highway 61, last Friday.

Elfer said the areas impacted are mostly residential and he didn’t believe any businesses have been affected, emphasizing that downtown Vicksburg is still safe for visitors. He said Warren County has worked with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency to secure pumps and barriers.

“Everybody thus far has been very cooperative,” he said. “We continue to tell people stay out of the flood areas, don’t drive around barricades and don’t drive around road close signs. Not only is it illegal, it’s dangerous.”

NWS projects the river to stay at flood stage in Vicksburg until May 6. The river reached its record crest of 57.1 feet in 2011.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

With domestic violence law, victims ‘will be a number with a purpose,’ mother says

Joslin Napier. Carlos Collins. Bailey Mae Reed.

They are among Mississippi domestic violence homicide victims whose family members carried their photos as the governor signed a bill that will establish a board to study such deaths and how to prevent them.

Tara Gandy, who lost her daughter Napier in Waynesboro in 2022, said it’s a moment she plans to tell her 5-year-old grandson about when he is old enough. Napier’s presence, in spirit, at the bill signing can be another way for her grandson to feel proud of his mother.

“(The board) will allow for my daughter and those who have already lost their lives to domestic violence … to no longer be just a number,” Gandy said. “They will be a number with a purpose.”

Family members at the April 15 private bill signing included Ashla Hudson, whose son Collins, died last year in Jackson. Grandparents Mary and Charles Reed and brother Colby Kernell attended the event in honor of Bailey Mae Reed, who died in Oxford in 2023.

Joining them were staff and board members from the Mississippi Coalition Against Domestic Violence, the statewide group that supports shelters and advocated for the passage of Senate Bill 2886 to form a Domestic Violence Facility Review Board.

The law will go into effect July 1, and the coalition hopes to partner with elected officials who will make recommendations for members to serve on the board. The coalition wants to see appointees who have frontline experience with domestic violence survivors, said Luis Montgomery, public policy specialist for the coalition.

A spokesperson from Gov. Tate Reeves’ office did not respond to a request for comment Friday.

Establishment of the board would make Mississippi the 45th state to review domestic violence fatalities.

Montgomery has worked on passing a review board bill since December 2023. After an unsuccessful effort in 2024, the coalition worked to build support and educate people about the need for such a board.

In the recent legislative session, there were House and Senate versions of the bill that unanimously passed their respective chambers. Authors of the bills are from both political parties.

The review board is tasked with reviewing a variety of documents to learn about the lead up and circumstances in which people died in domestic violence-related fatalities, near fatalities and suicides – records that can include police records, court documents, medical records and more.

From each review, trends will emerge and that information can be used for the board to make recommendations to lawmakers about how to prevent domestic violence deaths.

“This is coming at a really great time because we can really get proactive,” Montgomery said.

Without a board and data collection, advocates say it is difficult to know how many people have died or been injured in domestic-violence related incidents.

A Mississippi Today analysis found at least 300 people, including victims, abusers and collateral victims, died from domestic violence between 2020 and 2024. That analysis came from reviewing local news stories, the Gun Violence Archive, the National Gun Violence Memorial, law enforcement reports and court documents.

Some recent cases the board could review are the deaths of Collins, Napier and Reed.

In court records, prosecutors wrote that Napier, 24, faced increased violence after ending a relationship with Chance Fabian Jones. She took action, including purchasing a firearm and filing for a protective order against Jones.

Jones’s trial is set for May 12 in Wayne County. His indictment for capital murder came on the first anniversary of her death, according to court records.

Collins, 25, worked as a nurse and was from Yazoo City. His ex-boyfriend Marcus Johnson has been indicted for capital murder and shooting into Collins’ apartment. Family members say Collins had filed several restraining orders against Johnson.

Johnson was denied bond and remains in jail. His trial is scheduled for July 28 in Hinds County.

He was a Jackson police officer for eight months in 2013. Johnson was separated from the department pending disciplinary action leading up to immediate termination, but he resigned before he was fired, Jackson police confirmed to local media.

Reed, 21, was born and raised in Michigan and moved to Water Valley to live with her grandparents and help care for her cousin, according to her obituary.

Kylan Jacques Phillips was charged with first degree murder for beating Reed, according to court records. In February, the court ordered him to undergo a mental evaluation to determine if he is competent to stand trial, according to court documents.

At the bill signing, Gandy said it was bittersweet and an honor to meet the families of other domestic violence homicide victims.

“We were there knowing we are not alone, we can travel this road together and hopefully find ways to prevent and bring more awareness about domestic violence,” she said.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mississippi Today

Court to rule on DeSoto County Senate districts with special elections looming

A federal three-judge panel will rule in coming days on how political power in northwest Mississippi will be allocated in the state Senate and whether any incumbents in the DeSoto County area might have to campaign against each other in November special elections.

The panel, comprised of all George W. Bush-appointed judges, ordered state officials last week to, again, craft a new Senate map for the area in the suburbs of Memphis. The panel has held that none of the state’s prior maps gave Black voters a realistic chance to elect candidates of their choice.

The latest map proposed by the all-Republican State Board of Election Commissioners tweaked only four Senate districts in northwest Mississippi and does not pit any incumbent senators against each other.

The state’s proposal would keep the Senate districts currently held by Sen. Michael McLendon, a Republican from Hernando and Sen. Kevin Blackwell, a Republican from Southaven, in majority-white districts.

But it makes Sen. David Parker’s district a slightly majority-Black district. Parker, a white Republican from Olive Branch, would run in a district with a 50.1% black voting-age population, according to court documents.

The proposal also maintains the district held by Sen. Reginald Jackson, a Democrat from Marks, as a majority-Black district, although it reduces the Black voting age population from 61% to 53%.

Gov. Tate Reeves, Secretary of State Michael Watson, and Attorney General Lynn Fitch comprise the State Board of Election Commissioners. Reeves and Watson voted to approve the plan. But Watson, according to meeting documents, expressed a wish that the state had more time to consider different proposals.

Fitch did not attend the meeting, but Deputy Attorney General Whitney Lipscomb attended in her place. Lipscomb voted against the map, although it is unclear why. Fitch’s office declined to comment on why she voted against the map because it involves pending litigation.

The reason for redrawing the districts is that the state chapter of the NAACP and Black voters in the state sued Mississippi officials for drawing legislative districts in a way that dilutes Black voting power.

The plaintiffs, represented by the ACLU, are likely to object to the state’s newest proposal, and they have until April 29 to file an objection with the court

The plaintiffs have put forward two alternative proposals for the area in the event the judges rule against the state’s plans.

The first option would place McLendon and Blackwell in the same district, and the other would place McLendon and Jackson in the same district.

It is unclear when the panel of judges will issue a ruling on the state’s plan, but they will not issue a ruling until the plaintiffs file their remaining court documents next week.

While the November election is roughly six months away, changing legislative districts across counties and precincts is technical work, and local election officials need time to prepare for the races.

The judges have not yet ruled on the full elections calendar, but U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Leslie Southwick said at a hearing earlier this month that the panel was committed have the elections in November.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days agoJim talks with Rep. Robert Andrade about his investigation into the Hope Florida Foundation

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days agoHighs in the upper 80s Saturday, backdoor cold front will cool us down a bit on Easter Sunday

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days agoValerie Storm Tracker

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days agoU.S. Supreme Court pauses deportations under wartime law

-

Mississippi Today5 days ago

Mississippi Today5 days ago‘Trainwreck on the horizon’: The costly pains of Mississippi’s small water and sewer systems

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days agoPrayer Vigil Held for Ronald Dumas Jr., Family Continues to Pray for His Return | April 21, 2025 | N

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days agoMeteorologist Chita Craft is tracking a Severe Thunderstorm Warning that's in effect now

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days agoNo. 3 Texas walks off No. 9 LSU again to capture crucial SEC softball series