Mississippi Today

The Sheriff, His Girlfriend and His Illegal Subpoenas

In 2014, Bryan Bailey, the sheriff of Rankin County, Miss., made what seemed like a series of routine requests of the local district attorney’s office.

He needed grand jury subpoenas, he said, to force the phone company to turn over records of calls and text messages for what he called a “confidential internal investigation.”

Sheriff Bailey scrawled a brief note on a subpoena form and gave it to a paralegal in the district attorney’s office. “Please keep this confidential between you and I,” the note read. “Possible wrongdoing by school district employee.”

But his requests had nothing to do with alleged wrongdoing, or any criminal investigation, according to a previously undisclosed report obtained by The New York Times and the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting at Mississippi Today. Instead, Sheriff Bailey tapped into the power of a grand jury at least eight times over a year to spy on his married girlfriend and the school employee with whom she was also “unfaithful,” the documents show.

The investigative report, compiled in 2016 by the district attorney at the time, Michael Guest, laid out evidence that Sheriff Bailey had duped the prosecutor’s office and potentially violated state law on fraud, a felony that carries up to five years in prison.

Mr. Guest, now a U.S. congressman and chairman of the House Committee on Ethics, decided he could not pursue the case further because of conflicts of interest, including his years long friendship with the sheriff. He told two local judges what he had discovered and passed his investigation on to the state attorney general.

And that’s where the matter ended.

According to interviews with former staff members in the attorney general’s office, no one questioned the sheriff or conducted a full investigation. Jim Hood, the attorney general at the time, asked a senior attorney to look into the matter but did not pursue criminal charges.

Neither his office nor Mr. Guest informed the state agency that oversees law enforcement certifications, even though Mr. Guest was a voting member of the board. That agency could have reviewed the allegations and possibly revoked Sheriff Bailey’s certification.

For seven years, every elected official who learned of the allegations kept them secret from the public, leaving citizens of Rankin County in the dark, even as they twice voted to re-elect Sheriff Bailey. He is on the verge of another re-election, having won the Republican primary in August and facing no opponent in November.

His conduct is the latest in a series of examples uncovered by The Times and Mississippi Today of how sheriffs in Mississippi can act with impunity, often using the power of their office to weaponize the criminal justice system for their own benefit with no risk of being held accountable, even when faced with serious allegations of abuse.

Sheriff Bailey and his department have been under national scrutiny and a federal civil rights investigation since five deputies and a local police officer pleaded guilty this year to torturing two Black men and shooting one of them in the mouth.

Sheriff Bailey did not respond to requests for comment. Nor did local officials aware of the allegations and the report, including then-Circuit Court Judges John H. Emfinger and William E. Chapman III. Mr. Guest declined to comment.

Mr. Hood said in a statement that he did not remember all the details of how the case was handled, but he insisted that his office had investigated and made the right call in not prosecuting.

He said he had passed Mr. Guest’s report on to Ed Snyder, who was a special assistant attorney general working part time. Mr. Snyder recalled receiving the report but said he was asked to “take a look,” not to investigate. He said he only reviewed what criminal statutes might be used to prosecute.

Normally, a case involving possible public corruption would have been handled by the Public Integrity Division within the attorney general’s office. Mr. Hood could not recall why he did not send the case there, but said he trusted Mr. Snyder’s judgment.

Mr. Hood’s best recollection, he said, is that he chose not to pursue charges because the sheriff had a plausible reason for investigating the people targeted by the subpoenas. He said he believed his former office’s investigation had found that those people were involved in “some criminal activity, maybe drugs or a home burglary.”

But neither of the people whose phone calls and texts were subpoenaed were ever charged in a drug or burglary case, or any other criminal case. And there is no public evidence that indicates the subpoenas were part of a criminal inquiry.

If there had been a legitimate criminal case involving Sheriff Bailey’s girlfriend, the sheriff should not have been involved in the case at all, said Matthew Steffey, a lawyer and a professor at the Mississippi College School of Law.

“There was an obvious and profound conflict of interest here,” he said. “If there was a legitimate criminal investigation, the sheriff should not have been subpoenaing his own girlfriend’s phone records. And he certainly cannot do it without the knowledge or the direction of the district attorney’s office.”

That the sheriff has not been prosecuted or otherwise held accountable, despite the evidence against him, reflects “an utter failure of our criminal justice system,” Professor Steffey added.

Mr. Guest began investigating Sheriff Bailey in the spring of 2016 after receiving a tip about his use of grand jury subpoenas.

He was initially “very doubtful” and began looking into the matter “in hopes to put these rumors quickly to rest,” he wrote in his investigative report.

But he soon discovered a series of phone record requests that appeared suspicious based on the numbers that Sheriff Bailey had targeted.

One of the numbers belonged to Kristi Pennington Shanks, an administrative assistant in the sheriff’s office who had begun a relationship with Sheriff Bailey while she was married, according to the report. The other belonged to a local school district employee with whom Ms. Shanks also had been involved, the report states.

Mr. Guest wrote in his report that his office was not part of any investigation into the school employee or Ms. Shanks. Ms. Shanks, who remains the sheriff’s girlfriend, did not respond to requests for comment.

According to copies of the subpoena requests included in Mr. Guest’s report, the first request came from a Rankin County deputy who emailed the district attorney’s office on Jan. 30, 2014. He asked a paralegal there, Kim Amason, to write up and stamp a subpoena for a list of the school employee’s outgoing phone calls that month. Ms. Amason did not respond to a request for comment.

Throughout 2014, there were at least seven more subpoenas for texts and calls associated with the numbers of the former school employee and Ms. Shanks. Most of the requests directed phone companies to send records to Sheriff Bailey.

Grand juries, composed of up to two dozen people selected from the community, operate in secret. They investigate potential crimes, subpoena evidence, compel testimony and decide whether charges should be filed.

Practices vary by state, but typically the district attorney’s office files paperwork for subpoenas on behalf of the grand jury, without a review by jurors or a judge. Law enforcement officers can request such subpoenas, serve them on the person or entity holding the records, and directly collect the evidence. Afterward, it is normal practice for officers to turn this evidence over to prosecutors, who maintain permanent investigative files on cases.

Under Mississippi law, grand jury subpoenas can be issued only to aid a legitimate criminal investigation. Violators can be prosecuted for fraud and face years in prison.

A decade ago, the state attorney general’s office under Mr. Hood charged a former Meridian police officer with wire fraud after he forged signatures on a grand jury subpoena to get his wife’s phone records when he suspected she had been unfaithful. He was convicted and spent a year in prison.

Experts said the statute of limitations had passed to bring any potential state charges that might have applied to Sheriff Bailey’s actions. But details of the case could be getting a second look by federal authorities.

Fred Shanks, whose ex-wife became Sheriff Bailey’s girlfriend and a target of his subpoenas, said he was recently interviewed by the F.B.I. Mr. Shanks is Mr. Guest’s cousin and was the source of the original tip that prompted him to investigate.

In an interview with reporters, Mr. Shanks said he told authorities several times that both his and his girlfriend’s phone’s were being improperly tracked by Sheriff Bailey.

In 2015, after he got divorced, Mr. Shanks started dating Kristen Liberto, an investigator with the Rankin County Sheriff’s Office.

Ms. Liberto said her professional relationship with the sheriff then soured. She found herself under review for leaving work to go to a chiropractor, and she discovered a tracking device attached to her car, she said. In October 2015, she said, Sheriff Bailey called her into his office and gave her two options: resign, or be arrested for filling out fraudulent timecards.

She resigned and felt “absolutely devastated,” she said.

The sheriff also demanded that Ms. Liberto return a piece of county equipment that was in her possession. “I want my tracker back,” she recalled him saying.

Then, in 2016, Mr. Shanks received a tip that Sheriff Bailey had previously obtained his and his ex-wife’s phone records. He said he immediately called Mr. Guest. “There were multiple people who could have done something about this, but they did nothing,” said Mr. Shanks, who has represented Rankin County in the Mississippi Legislature since 2018. “It begs the question, how many other people did he do this to?”

Ilyssa Daly examines the power of sheriffs’ offices in Mississippi as part of The Times’s Local Investigations Fellowship. Jerry Mitchell, co-founder of the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting that’s now part of Mississippi Today, is an investigative reporter who has examined civil rights-era cold murder cases in the state for more than 30 years.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1977, Alex Haley awarded Pulitzer for ‘Roots’

April 19, 1977

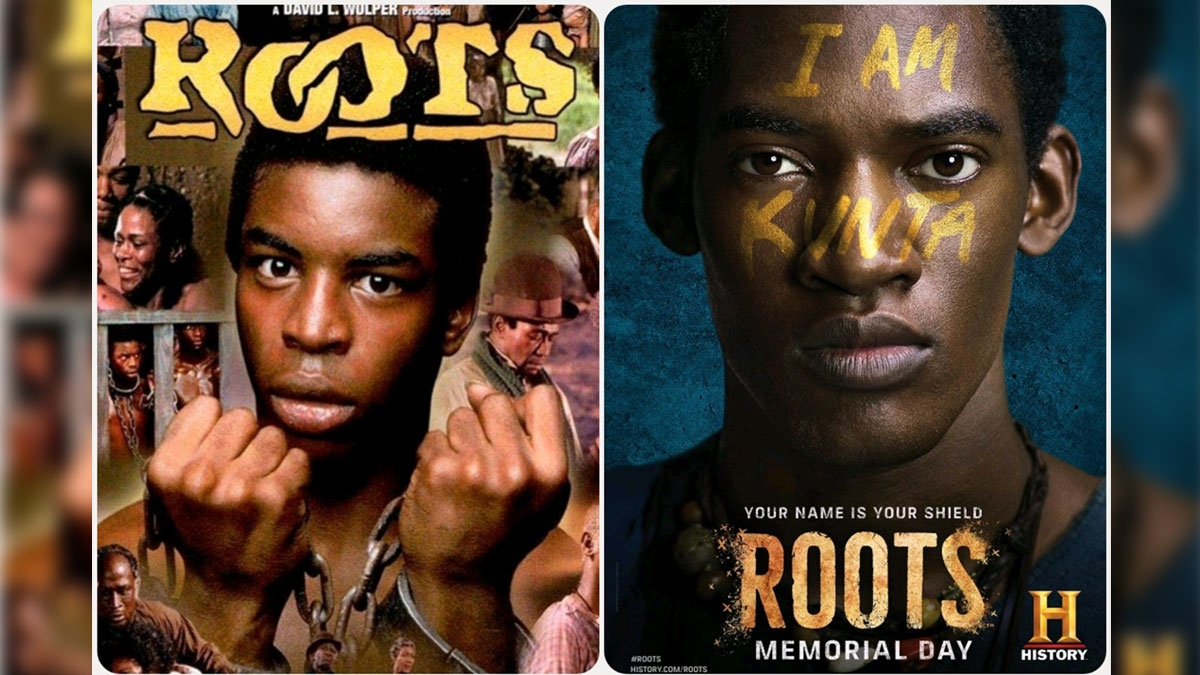

Alex Haley was awarded a special Pulitzer Prize for “Roots,” which was also adapted for television.

Network executives worried that the depiction of the brutality of the slave experience might scare away viewers. Instead, 130 million Americans watched the epic miniseries, which meant that 85% of U.S. households watched the program.

The miniseries received 36 Emmy nominations and won nine. In 2016, the History Channel, Lifetime and A&E remade the miniseries, which won critical acclaim and received eight Emmy nominations.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Speaker White wants Christmas tree projects bill included in special legislative session

House Speaker Jason White sent a terse letter to Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann on Thursday, saying House leaders are frustrated with Senate leaders refusing to discuss a “Christmas tree” bill spending millions on special projects across the state.

The letter signals the two Republican leaders remain far apart on setting an overall $7 billion state budget. Bickering between the GOP leaders led to a stalemate and lawmakers ending their regular 2025 session without setting a budget. Gov. Tate Reeves plans to call them back into special session before the new budget year starts July 1 to avoid a shutdown, but wants them to have a budget mostly worked out before he does so.

White’s letter to Hosemann, which contains words in all capital letters that are underlined and italicized, said that the House wants to spend cash reserves on projects for state agencies, local communities, universities, colleges, and the Mississippi Department of Transportation.

“We believe the Senate position to NOT fund any local infrastructure projects is unreasonable,” White wrote.

The speaker in his letter noted that he and Hosemann had a meeting with the governor on Tuesday. Reeves, according to the letter, advised the two legislative leaders that if they couldn’t reach an agreement on how to disburse the surplus money, referred to as capital expense money, they should not spend any of it on infrastructure.

A spokesperson for Hosemann said the lieutenant governor has not yet reviewed the letter, and he was out of the office on Thursday working with a state agency.

“He is attending Good Friday services today, and will address any correspondence after the celebration of Easter,” the spokesperson said.

Hosemann has recently said the Legislature should set an austere budget in light of federal spending cuts coming from the Trump administration, and because state lawmakers this year passed a measure to eliminate the state income tax, the source of nearly a third of the state’s operating revenue.

Lawmakers spend capital expense money for multiple purposes, but the bulk of it — typically $200 million to $400 million a year — goes toward local projects, known as the Christmas Tree bill. Lawmakers jockey for a share of the spending for their home districts, in a process that has been called a political spoils system — areas with the most powerful lawmakers often get the largest share, not areas with the most needs. Legislative leaders often use the projects bill as either a carrot or stick to garner votes from rank and file legislators on other issues.

A Mississippi Today investigation last year revealed House Ways and Means Chairman Trey Lamar, a Republican from Sentobia, has steered tens of millions of dollars in Christmas tree spending to his district, including money to rebuild a road that runs by his north Mississippi home, renovate a nearby private country club golf course and to rebuild a tiny cul-de-sac that runs by a home he has in Jackson.

There is little oversight on how these funds are spent, and there is no requirement that lawmakers disburse the money in an equal manner or based on communities’ needs.

In the past, lawmakers borrowed money for Christmas tree bills. But state coffers have been full in recent years largely from federal pandemic aid spending, so the state has been spending its excess cash. White in his letter said the state has “ample funds” for a special projects bill.

“We, in the House, would like to sit down and have an agreement with our Senate counterparts on state agency Capital Expenditure spending AND local projects spending,” White wrote. “It is extremely important to our agencies and local governments. The ball is in your court, and the House awaits your response.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mississippi Today

Advocate: Election is the chance for Jackson to finally launch in the spirit of Blue Origin

Editor’s note: This essay is part of Mississippi Today Ideas, a platform for thoughtful Mississippians to share fact-based ideas about our state’s past, present and future. You can read more about the section here.

As the world recently watched the successful return of Blue Origin’s historic all-women crew from space, Jackson stands grounded. The city is still grappling with problems that no rocket can solve.

But the spirit of that mission — unity, courage and collective effort — can be applied right here in our capital city. Instead of launching away, it is time to launch together toward a more just, functioning and thriving Jackson.

The upcoming mayoral runoff election on April 22 provides such an opportunity, not just for a new administration, but for a new mindset. This isn’t about endorsements. It’s about engagement.

It’s a moment for the people of Jackson and Hinds County to take a long, honest look at ourselves and ask if we have shown up for our city and worked with elected officials, instead of remaining at odds with them.

It is time to vote again — this time with deeper understanding and shared responsibility. Jackson is in crisis — and crisis won’t wait.

According to the U.S. Census projections, Jackson is the fastest-shrinking city in the United States, losing nearly 4,000 residents in a single year. That kind of loss isn’t just about numbers. It’s about hope, resources, and people’s decision to give up rather than dig in.

Add to that the long-standing issues: a crippled water system, public safety concerns, economic decline and a sense of division that often pits neighbor against neighbor, party against party and race against race.

Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba has led through these storms, facing criticism for his handling of the water crisis, staffing issues and infrastructure delays. But did officials from the city, the county and the state truly collaborate with him or did they stand at a distance, waiting to assign blame?

On the flip side, his runoff opponent, state Sen. John Horhn, who has served for more than three decades, is now seeking to lead the very city he has represented from the Capitol. Voters should examine his legislative record and ask whether he used his influence to help stabilize the administration or only to position himself for this moment.

Blaming politicians is easy. Building cities is hard. And yet that is exactly what’s needed. Jackson’s future will not be secured by a mayor alone. It will take so many of Jackson’s residents — voters, business owners, faith leaders, students, retirees, parents and young people — to move this city forward. That’s the liftoff we need.

It is time to imagine Jackson as a capital city where clean, safe drinking water flows to every home — not just after lawsuits or emergencies, but through proactive maintenance and funding from city, state and federal partnerships. The involvement of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in the effort to improve the water system gives the city leverage.

Public safety must be a guarantee and includes prevention, not just response, with funding for community-based violence interruption programs, trauma services, youth job programs and reentry support. Other cities have done this and it’s working.

Education and workforce development are real priorities, preparing young people not just for diplomas but for meaningful careers. That means investing in public schools and in partnerships with HBCUs, trade programs and businesses rooted right here.

Additionally, city services — from trash collection to pothole repair — must be reliable, transparent and equitable, regardless of zip code or income. Seamless governance is possible when everyone is at the table.

Yes, democracy works because people show up. Not just to vote once, but to attend city council meetings, serve on boards, hold leaders accountable and help shape decisions about where resources go.

This election isn’t just about who gets the title of mayor. It’s about whether Jackson gets another chance at becoming the capital city Mississippi deserves — a place that leads by example and doesn’t lag behind.

The successful Blue Origin mission didn’t happen by chance. It took coordinated effort, diverse expertise and belief in what was possible. The same is true for this city.

We are not launching into space. But we can launch a new era marked by cooperation over conflict, and by sustained civic action over short-term outrage.

On April 22, go vote. Vote not just for a person, but for a path forward because Jackson deserves liftoff. It starts with us.

Pauline Rogers is a longtime advocate for criminal justice reform and the founder of the RECH Foundation, an organization dedicated to supporting formerly incarcerated individuals as they reintegrate into society. She is a Transformative Justice Fellow through The OpEd Project Public Voices Fellowship.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days agoLawmakers used to fail passing a budget over policy disagreement. This year, they failed over childish bickering.

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days agoOn this day in 1873, La. courthouse scene of racial carnage

-

Local News6 days ago

Local News6 days agoSouthern Miss Professor Inducted into U.S. Hydrographer Hall of Fame

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoFoley man wins Race to the Finish as Kyle Larson gets first win of 2025 Xfinity Series at Bristol

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoFederal appeals court upholds ruling against Alabama panhandling laws

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days agoBellingrath Gardens previews its first Chinese Lantern Festival

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoSevere weather has come and gone for Central Florida, but the rain went with it

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days ago1 dead after 7 people shot during large gathering at Crosby gas station, HCSO says