NASA via AP

Marcos Fernandez Tous, University of North Dakota

For about 15 minutes on July 21, 1961, American astronaut Gus Grissom felt at the top of the world – and indeed he was.

Grissom crewed the Liberty Bell 7 mission, a ballistic test flight that launched him through the atmosphere from a rocket. During the test, he sat inside a small capsule and reached a peak of over 100 miles up before splashing down in the Atlantic Ocean.

A Navy ship, the USS Randolph, watched the successful end of the mission from a safe distance. Everything had gone according to plan, the controllers at Cape Canaveral were exultant, and Grissom knew he had just entered a VIP club as the second American astronaut in history.

Grissom remained inside his capsule and swayed on the gentle ocean waves. While he waited for a helicopter to take him onto the USS Randolph’s dry deck, he finished recording some flight data. But then, things took an unexpected turn.

An incorrect command in the capsule’s explosives system caused the hatch to pop out, which let water flow into the tiny space. Grissom had also forgotten to close a valve in his spacesuit, so water began to seep into his suit as he fought to stay afloat.

After a dramatic escape from the capsule, he struggled to keep his head above the surface while giving signals to the helicopter pilot that something had gone wrong. The helicopter managed to save him at the last instant.

Grissom’s near-death escape remains one of the most dramatic splashdowns in history. But splashing down into water remains one of the most common ways astronauts return to Earth. I am a professor of aerospace engineering who studies the mechanisms involved in these phenomena. Fortunately, most splashdowns are not quite that nerve-racking, at least on paper.

AP Photo/Barry Sweet

Splashdown explained

Before it can perform a safe landing, a spacecraft returning to Earth needs to slow down. While it is careening back to Earth, a spacecraft has a lot of kinetic energy. Friction with the atmosphere introduces drag, which slows down the spacecraft. The friction converts the spacecraft’s kinetic energy to thermal energy, or heat.

All this heat radiates out into the surrounding air, which gets really, really hot. Since reentry velocities can be several times the speed of sound, the force of the air pushing back against the vehicle turns the vehicle’s surroundings into a scorching flow that’s about 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit (1,500 degrees Celsius). In the case of SpaceX’s massive Starship rocket, this temperature even reaches 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (nearly 1,700 degrees Celsius).

Unfortunately, no matter how quickly this transfer happens, there’s still not enough time during reentry for the vehicle to slow down to a safe enough velocity not to crash. So, the engineers resort to other methods that can slow down a spacecraft during splashdown.

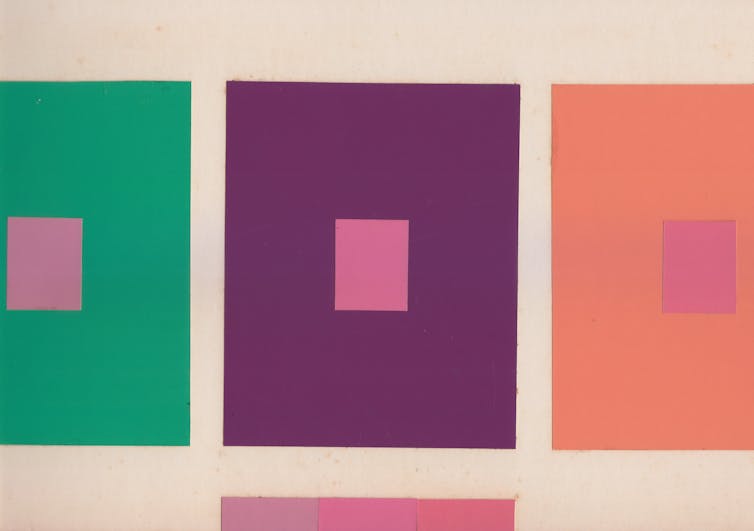

Parachutes are the first option. NASA typically uses designs with bright colors, such as orange, which make them easy to spot. They’re also huge, with diameters of over 100 feet, and each reentry vehicle usually uses more than one for the best stability.

The first parachutes deployed, called drag parachutes, eject when the vehicle’s velocity falls below about 2,300 feet per second (700 meters per second).

Even then, the rocket can’t crash against a hard surface. It needs to land somewhere that will cushion the impact. Researchers figured out early on that water makes an excellent shock absorber. Thus, splashdown was born.

Why water?

Water has a relatively low viscosity – that is, it deforms fast under stress – and it has a density much lower than hard rock. These two qualities make it ideal for landing spacecraft. But the other main reason water works so well is because it covers 70% of the planet’s surface, so the chances of hitting it are high when you’re falling from space.

The science behind splashdown is complex, as a long history proves.

In 1961, the U.S. conducted the first crewed splashdowns in history. These used Mercury reentry capsules.

These capsules had a roughly conical shape and fell with the base toward the water. The astronaut inside sat facing upward. The base absorbed most of the heat, so researchers designed a heat shield that boiled away as the capsule shot through the atmosphere.

As the capsule slowed and the friction reduced, the air got cooler, which made it able to absorb the excess heat on the vehicle, thereby cooling it down as well. At a sufficiently low speed, the parachutes would deploy.

Splashdown occurs at a velocity of about 80 feet per second (24 meters per second). It’s not exactly a smooth impact, but that’s slow enough for the capsule to thwack into the ocean and absorb shock from the impact without damaging its structure, its payload or any astronauts inside.

Following the Challenger loss in 1986, when the space shuttle Challenger broke apart shortly after liftoff, engineers started focusing their vehicle designs on what’s called the crashworthiness phenomena – or the degree of damage a craft takes after it hits a surface.

Now, all vehicles need to prove that they can offer a chance of survival on water after returning from space. Researchers build complex models, then test them with laboratory experiments to prove that the structure is sturdy enough to meet this requirement.

Onto the future

Between 2021 and June 2024, seven of SpaceX’s Dragon capsules performed flawless splashdowns on their return from the International Space Station.

On June 6, the most powerful rocket to date, SpaceX’s Starship, made a phenomenal vertical splashdown into the Indian Ocean. Its rocket boosters kept firing while approaching the surface, creating an extraordinary cloud of hissing steam surrounding the nozzles.

SpaceX has been using splashdowns to recover the Dragon capsules after launch, with no significant damage to their critical parts, so that it can recycle them for future missions. Unlocking this reusability will allow private companies to save millions of dollars in infrastructure and reduce mission costs.

Splashdown continues to be the most common spacecraft reentry tactic, and with more space agencies and private companies shooting for the stars, we’re likely to see plenty more take place in the future.

This article has been updated to correct that SpaceX has been recovering their Dragon capsules during splashdown.![]()

Marcos Fernandez Tous, Assistant Professor of Space Studies, University of North Dakota

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.