A grower shows off his lush cassava garden. Stephen Wooding, CC BY-ND

Stephen Wooding, University of California, Merced

The three staple crops dominating modern diets – corn, rice and wheat – are familiar to Americans. However, fourth place is held by a dark horse: cassava.

While nearly unknown in temperate climates, cassava is a key source of nutrition throughout the tropics. It was domesticated 10,000 years ago, on the southern margin of the Amazon basin in Brazil, and spread from there throughout the region. With a scraggly stem a few meters tall, a handful of slim branches and modest, hand-shaped leaves, it doesn’t look like anything special. Cassava’s humble appearance, however, belies an impressive combination of productivity, toughness and diversity.

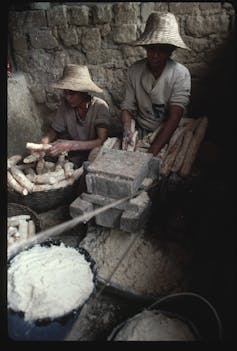

People preparing to process cassava, with some peeled tubers in the foreground.

Over the course of millennia, Indigenous peoples bred it from a weedy wild plant into a crop that stores prodigious quantities of starch in potatolike tubers, thrives in Amazonia’s poor soils and is nearly invulnerable to pests.

Cassava’s many assets would seem to make it the ideal crop. But there’s a problem: Cassava is highly poisonous.

How can cassava be so toxic, yet still dominate diets in Amazonia? It’s all down to Indigenous ingenuity. For the past 10 years, my collaborator, César Peña, and I have been studying cassava gardens on the Amazon River and its myriad tributaries in Peru. We have discovered scores of cassava varieties, growers using sophisticated breeding strategies to manage its toxicity, and elaborate methods for processing its dangerous yet nutritious products.

Long history of plant domestication

One of the most formidable challenges faced by early humans was getting enough to eat. Our ancient ancestors relied on hunting and gathering, catching prey on the run and collecting edible plants at every opportunity. They were astonishingly good at it. So good that their populations soared, surging out of humanity’s birthplace in Africa 60,000 years ago.

Even so, there was room for improvement. Searching the landscape for food burns calories, the very resource being sought. This paradox forced a trade-off for the hunter-gatherers: burn calories searching for food or conserve calories by staying home. The trade-off was nearly insurmountable, but humans found a way.

A little more than 10,000 years ago, they cleared the hurdle with one of the most transformative innovations in history: plant and animal domestication. People discovered that when plants and animals were tamed, they no longer needed to be chased down. And they could be selectively bred, producing larger fruits and seeds and bulkier muscles to eat.

Cassava was the champion domesticated plant in the neotropics. After its initial domestication, it diffused through the region, reaching sites as far north as Panama within a few thousand years. Growing cassava didn’t completely eliminate people’s need to search the forest for food, but it lightened the load, providing a plentiful, reliable food supply close to home.

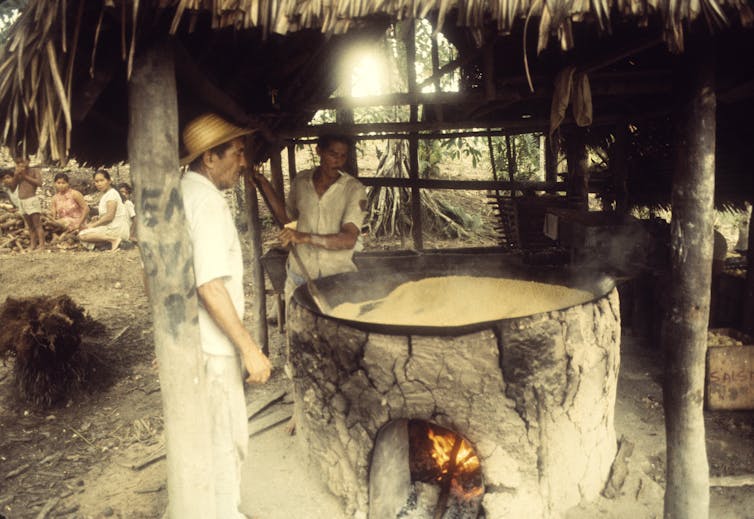

Today, almost every rural family across the Amazon has a garden. Visit any household and you will find cassava roasting on the fire, being toasted into a chewy flatbread called casabe, fermenting into the beer called masato, and steaming in soups and stews. Before adopting cassava in these roles, though, people had to figure out how to deal with its toxicity.

Processing a poisonous plant

One of cassava’s most important strengths, its pest resistance, is provided by a powerful defense system. The system relies on two chemicals produced by the plant, linamarin and linamarase.

These defensive chemicals are found inside cells throughout the cassava plant’s leaves, stem and tubers, where they usually sit idle. However, when cassava’s cells are damaged, by chewing or crushing, for instance, the linamarin and linamarase react, releasing a burst of noxious chemicals.

One of them is notorious: cyanide gas. The burst contains other nasty substances as well, including compounds called nitriles and cyanohydrins. Large doses of them are lethal, and chronic exposures permanently damage the nervous system. Together, these poisons deter herbivores so well that cassava is nearly impervious to pests.

Nobody knows how people first cracked the problem, but ancient Amazonians devised a complex, multistep process of detoxification that transforms cassava from inedible to delicious.

It begins with grinding cassava’s starchy roots on shredding boards studded with fish teeth, chips of rock or, most often today, a rough sheet of tin. Shredding mimics the chewing of pests, causing the release of the root’s cyanide and cyanohydrins. But they drift away into the air, not into the lungs and stomach like when they are eaten.

Next, the shredded cassava is placed in rinsing baskets where it is rinsed, squeezed by hand and drained repeatedly. The action of the water releases more cyanide, nitriles and cyanohydrins, and squeezing rinses them away.

Finally, the resulting pulp can be dried, which detoxifies it even further, or cooked, which finishes the process using heat. These steps are so effective that they are still used throughout the Amazon today, thousands of years since they were first devised.

A powerhouse crop poised to spread

Amazonians’ traditional methods of grinding, rinsing and cooking are a sophisticated and effective means of converting a poisonous plant into a meal. Yet, the Amazonians pushed their efforts even further, taming it into a true domesticated crop. In addition to inventing new methods for processing cassava, they began keeping track and selectively growing varieties with desirable characteristics, gradually producing a constellation of types used for different purposes.

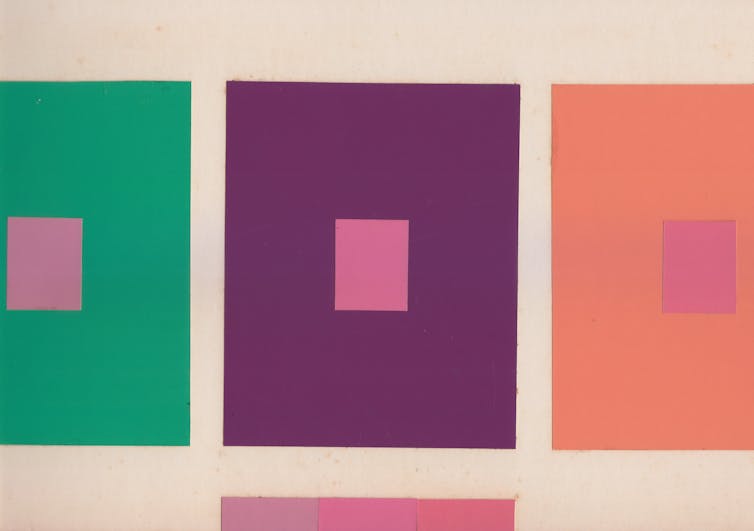

In our travels, we have found more than 70 distinct cassava varieties that are highly diverse, physically and nutritionally. They include types ranging in toxicity, some of which need laborious shredding and rinsing and others that can be cooked as is, though none can be eaten raw. There are also types with different tuber sizes, growth rates, starch production and drought tolerance.

Their diversity is prized, and they are often given fanciful names. Just as American supermarkets stock apples called Fuji, Golden Delicious and Granny Smith, Amazonian gardens stock cassavas called bufeo (dolphin), arpón (harpoon), motelo (tortoise) and countless others. This creative breeding cemented cassava’s place in Amazonian cultures and diets, ensuring its manageability and usefulness, just as the domestication of corn, rice and wheat cemented their places in cultures elsewhere.

While cassava has been ensconced in South and Central America for millennia, its story is far from over. In the age of climate change and mounting efforts toward sustainability, cassava is emerging as a possible world crop. Its durability and resilience make it easy to grow in variable environments, even when soils are poor, and its natural pest resistance reduces the need to protect it with industrial pesticides. In addition, while traditional Amazonian methods for detoxifying cassava can be slow, they are easy to replicate and speed up with modern machinery.

Workers package frozen cassava in bags at a Florida food processing plant.

Furthermore, the preference of Amazonian growers to maintain diverse types of cassava makes the Amazon a natural repository for genetic diversity. In modern hands, they can be bred to produce new types, fitting purposes beyond those in Amazonia itself. These advantages spurred the first export of cassava beyond South America in the 1500s, and its range quickly spanned tropical Africa and Asia. Today, production in nations such as Nigeria and Thailand far outpaces production in South America’s biggest producer, Brazil. These successes are raising optimism that cassava can become an eco-friendly source of nutrition for populations globally.

While cassava isn’t a familiar name in the U.S. just yet, it’s well on its way. It has long flown under the radar in the form of tapioca, a cassava starch used in pudding and boba tea. It’s also hitting the shelves in the snack aisle in the form of cassava chips and the baking aisle in naturally gluten-free flour. Raw cassava is an emerging presence, too, showing up under the names “yuca” and “manioc” in stores catering to Latin American, African and Asian populations.

Track some down and give it a try. Supermarket cassava is perfectly safe, and recipes abound. Cassava fritters, cassava fries, cassava cakes … cassava’s possibilities are nearly endless.

This article was co-authored by César Rubén Peña.![]()

Stephen Wooding, Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Heritage Studies, University of California, Merced

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.