Mississippi Today

The Emmett Till lynching has seen more than its share of liars. Is Tim Tyson one of them?

Award-winning historian Tim Tyson swears he heard admissions regarding Emmett Till’s lynching and another racial murder.

Admissions that weren’t recorded. Admissions that no one else heard. Admissions that he began hearing when he was 10.

“The question is not whether Tim Tyson fooled us once,” said Devery Anderson, author of “Emmett Till: The Murder That Shocked the World and Propelled the Civil Rights Movement.” “The question is whether he fooled us twice — and got away with it.”

Tyson has said he heard these admissions. He didn’t respond to requests for comments on the Till matter, but he has previously spoken to me, the FBI and others. All these are noted.

Tyson’s 2017 book, “The Blood of Emmett Till,” lit the bomb that exploded around the world with this claim: The white woman at the center of the Emmett Till case, Carolyn Bryant Donham, had admitted she lied when she testified that he had grabbed her around the waist and uttered obscenities.

For some in the Till family, such as his cousin, the Rev. Wheeler Parker, the revelation represented the hope of clearing his cousin’s name. “I was elated,” he said.

He had longed to hear Donham say she lied about Till and planned to forgive her when she did, said the longtime pastor. “I was raised to believe deeply in forgiveness. If you don’t forgive, God won’t forgive you.”

For some in the Till family, the revelation raised hopes of a possible prosecution. His cousin, Deborah Watts, said there should be “a revisiting of the evidence in light of this revelation,” and Bennie Thompson, the Democratic congressman for the Mississippi Delta, called for an investigation, saying this represented “an opportunity to bring some justice to an innocent 14-year-old boy.”

For Till’s cousin, Ollie Gordon, the revelation sounded like a ruse. She saw no logic, she said, in Donham sharing such information with someone she hardly knew.

“I thought, ‘Oh, here we go. This man wants to sell his book,’” she said. “He knew if he put that lie out, that was going to help him sell the book.”

The fact that Tyson spoke to Donham but no one in the Till family reflects his mindset, she said. “If you want first-hand information, you go to the family. If you want to write what you want to write, you just bypass the family.”

What Tyson did to the Till family is nothing new, she said. “People have made money off the blood of Emmett Till and the backs of the Till family. They’re all chasing the dollar. They don’t care how they get it.”

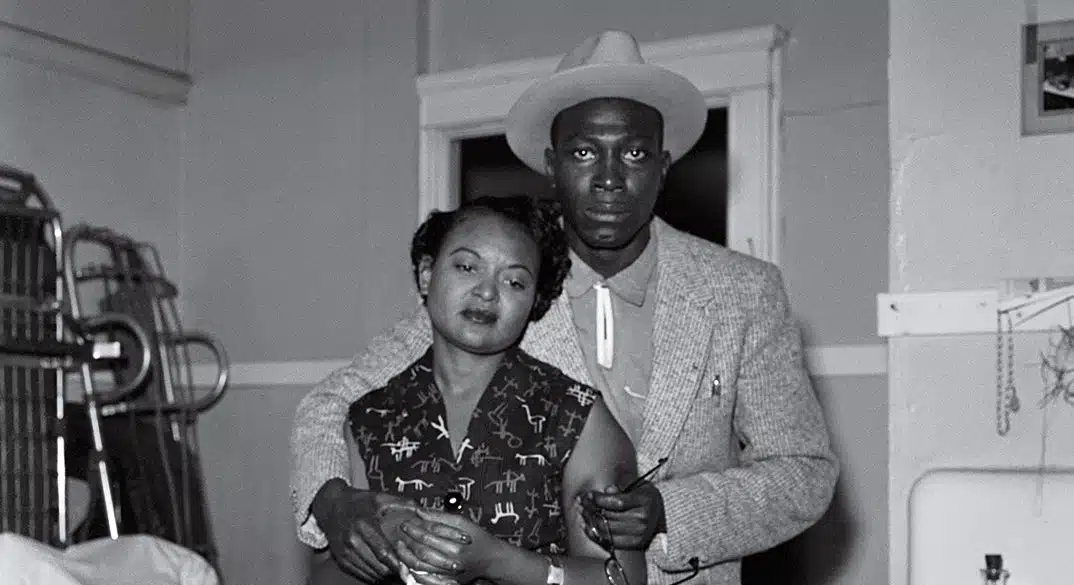

Parker still remembers the night of Aug. 28, 1955, when two men with guns stormed the Mississippi Delta home where he and his cousin, Emmett Till, were staying. He and Till had come from Chicago to visit relatives.

It was past 2 a.m., “as dark as a thousand midnights,” Parker said, when he heard angry voices from the gloom.

A flashlight shone down the hall, and he shut his eyes, ready to hear the shots that would steal his life. He trembled as he prayed, his 16 years flitting across his mind, he said. “I knew I wasn’t right with God.”

He heard the men say they “wanted the fat boy” that had “done the talking” at Bryant’s Grocery.

Before long, their steps receded and then their voices. They were gone, and so was his cousin, Emmett, whom kidnappers hauled to a remote barn and began beating.

After the first light came, Parker fled Mississippi.

For 30 years, he wasn’t asked about what he had seen, but in the decades since, he has spoken out.

While visiting one school, a white student told Parker that Till had “misbehaved” inside the store and got what he deserved.

“What could he have done to deserve that?” Parker said he responded. “I know he didn’t do anything.”

He and another cousin said they never saw Till do or say anything to Donham inside the store. All Till did was whistle at her after she walked outside, they said.

Several nights later, Till’s murderers executed their own judgment, Parker said. “They killed him for what? A whistle?”

Till’s torture lasted much of the night, and witnesses heard him screaming past dawn. By the time the sun began to peek over the horizon, his cries became fainter.

Silence followed.

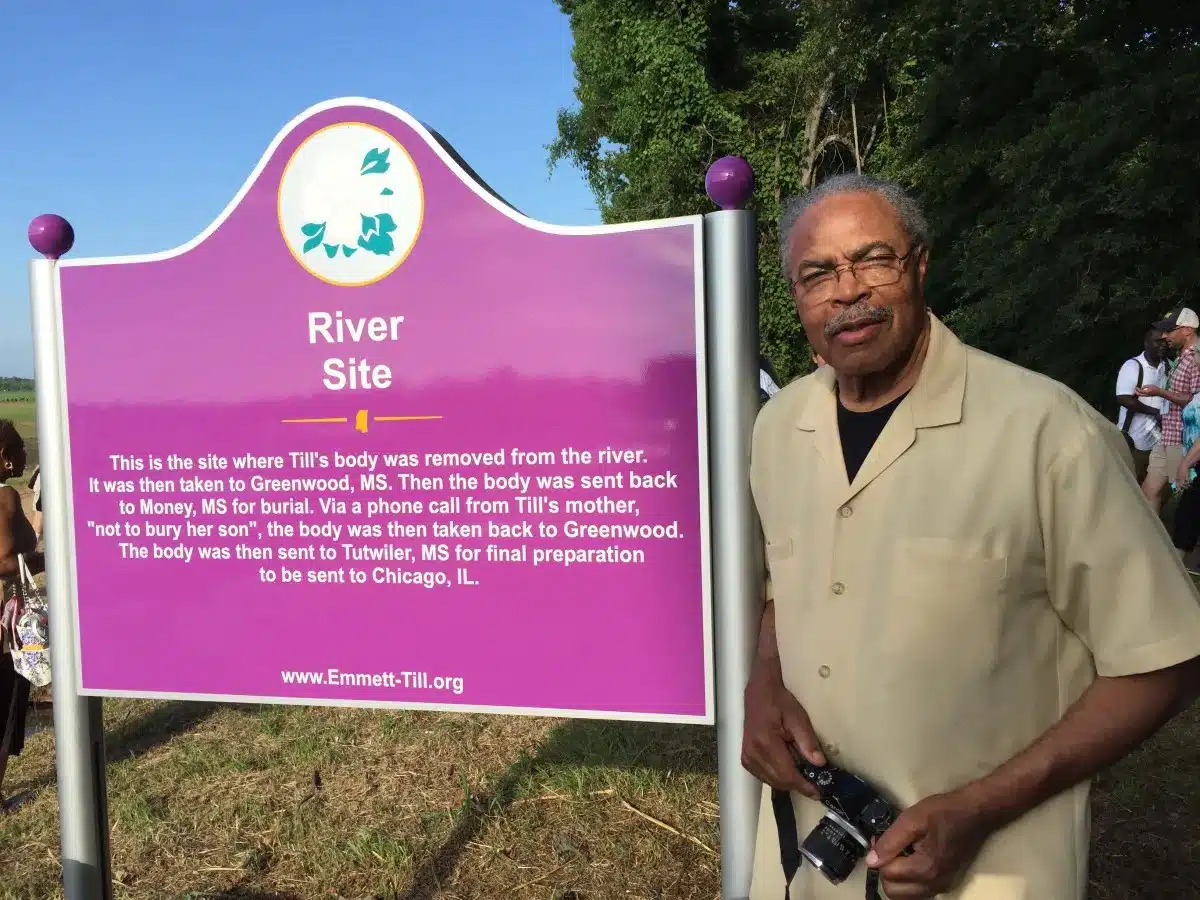

Till’s killers tried to bury their evil deeds by tying a 75-pound gin fan around his neck and tossing his body into water that fed into the Tallahatchie River.

The next day, when a deputy questioned two of the killers, J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant, they admitted they had kidnapped Till, but insisted they had released him unharmed. Days later, his body bobbed back to the river’s surface.

Sheriff Clarence Strider tried to bury Till’s brutalized body in a local cemetery to conceal the evil deed, but when his mother found out, she demanded his return to Chicago, where she opened his casket. “I wanted the world,” she said, “to see what I had seen.”

The lies continued after his funeral.

After arrests in the case, Bryant’s wife, Donham, told the defense lawyer that Till came into Bryant’s Grocery, grabbed her hand, asked for a date and said “goodbye” as he left.

But weeks later, the lawyer announced to reporters that Till had “mauled” Donham, and she echoed that lie from the witness stand. With the jury out of the courtroom, she claimed that Till had grabbed her around the waist, told her “you needn’t be afraid of me,” and said he had sex with white women before.

The sheriff got in on the lies, too. After Till was found, the sheriff told reporters the body had only been in the river a few days, released the body to a Black mortician and filled out a death certificate for Till.

But by the time the trial began, he had become a witness for the defense. He testified that the body had been in the water for at least 10 days and that he couldn’t tell the color of the skin — only that it was human. His words backed the incredulous defense claim that Till was still alive and that the NAACP had planted a cadaver in the river. (Five decades later, an autopsy and a DNA test proved that Till’s body was the one in his grave.)

The all-white jury acquitted the two men, despite believing they had killed Till, according to interviews the jurors gave Stephen Whitaker, who researched the case for his master’s thesis.

If those lies weren’t enough, journalist William Bradford Huie concealed the identities of other killers with his Look magazine article.

Huie told his editor that four men had taken part in the “torture-and-murder party,” but when the editor insisted on getting legal releases from all four, the murder party shrunk to two. (One trial witness, Willie Reed, identified four white men riding in the cab of the truck while three Black men held Till in the back.)

As for Huie, he had dreams of a Hollywood film and paid Till’s killers $3,150 for their rights.

The idea of Huie making “a deal with the murderers” angered Till’s mother, Mamie Till Mobley, and her attorney sent a cease and desist letter to United Artists, said Till documentary filmmaker Keith Beauchamp.

Huie’s 1956 article became gospel in the Till case until a new FBI investigation almost a half century later. Dale Killinger, who conducted that probe, said “the damage from those lies was deeper and broader than just Till’s murder.”

Three months before Till was killed, the Rev. George Lee was assassinated because he helped Black Mississippians register to vote in Belzoni. The sheriff claimed the shotgun pellets found in Lee’s face were loose fillings from his teeth.

Lamar Smith was gunned down in broad daylight on the courthouse lawn in Brookhaven. Despite the killer being covered in blood, the sheriff maintained there were no witnesses.

Killinger said these types of killings — and the lies that made them possible — “perpetuated generational trauma.”

By age 7, Tim Tyson was already spinning yarns.

He and his best friend “would lie there in the dark in the twin beds, and I would tell him stories, making them up as I went,” Tyson wrote in his memoir, “Blood Done Signed My Name.”

With each concocted tale, his friend cheered him on. “His fierce and unfeigned enthusiasm for these rambling odysseys,” Tyson wrote, “was like a drug to me.”

His friend even coined a name for them: “Tim’s Tall Tales.”

By the time Tyson telephoned me in 2008, he was already mesmerizing audiences with his stories of growing up in Oxford, North Carolina, and his memoir was being made into a movie.

Over lunch at Hal & Mal’s in Jackson, Tyson, who serves as a senior research scholar for the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, told me he landed an interview with Donham, the first interview I had ever heard of her giving to a historian. I congratulated him.

We talked about the Till case and much of the lore surrounding it.

Months later, we met in Jackson, he said he had finished talking with her. He told me her story mirrored her testimony, where she claimed Till had mauled her.

“You know she lied, don’t you?” I asked.

The statement surprised him, and afterward, I mailed him a copy of the statement she had made to the defense lawyer, where she mentioned nothing about Till grabbing her or talking about having sex with her.

He used that statement in his book and tried to talk with Donham again. She turned him down.

Much to my surprise, “The Blood of Emmett Till” hit the shelves in 2017 with the claim that Donham had admitted to Tyson that she had lied when she testified that Till had grabbed her around the waist and uttered obscenities.

News of the revelation spread like wildfire, first through top publications and television stations, before hitting Black radio, television, websites and word of mouth. “The Blood of Emmett Till” shot onto The New York Times Bestseller List and won the Robert F. Kennedy Award.

Calls arose for her prosecution, and the Justice Department began to look at the Till case again.

Questions soon surfaced. A source told me that Donham’s family was saying she didn’t recant, and I telephoned her then-daughter-in-law, Marsha Bryant, who said she was present the whole time and never heard the quotation Tyson attributed to Donham. Bryant said she had a copy of the transcript and the quote wasn’t in it.

When I reached out to Tyson in 2018, he confirmed he didn’t have the bombshell quote on tape, saying he was still setting up his recorder.

The book “Till” opens with Donham drinking coffee and serving Tyson a slice of pound cake. “She had never opened her door to a journalist or historian, let alone invited one for cake and coffee,” he wrote.

Bryant said Tyson actually brought the cake himself, and after the interview, he took it back with him.

Tyson told me his recorder wasn’t working when Donham said, “They’re all dead now anyway,” so he snatched up his notebook, began scribbling notes and heard her recantation.

But when the FBI began to investigate the matter, he gave investigators multiple accounts: that his recorder wasn’t working, that his recording was lost, that he didn’t realize he didn’t have her recantation on tape until much later.

Tyson wrote that Donham handed him a trial transcript and the memoir. Bryant disputed that, saying Donham never handed Tyson anything.

Tyson wrote that after Donham handed him the transcript, she said, “That part is not true.”

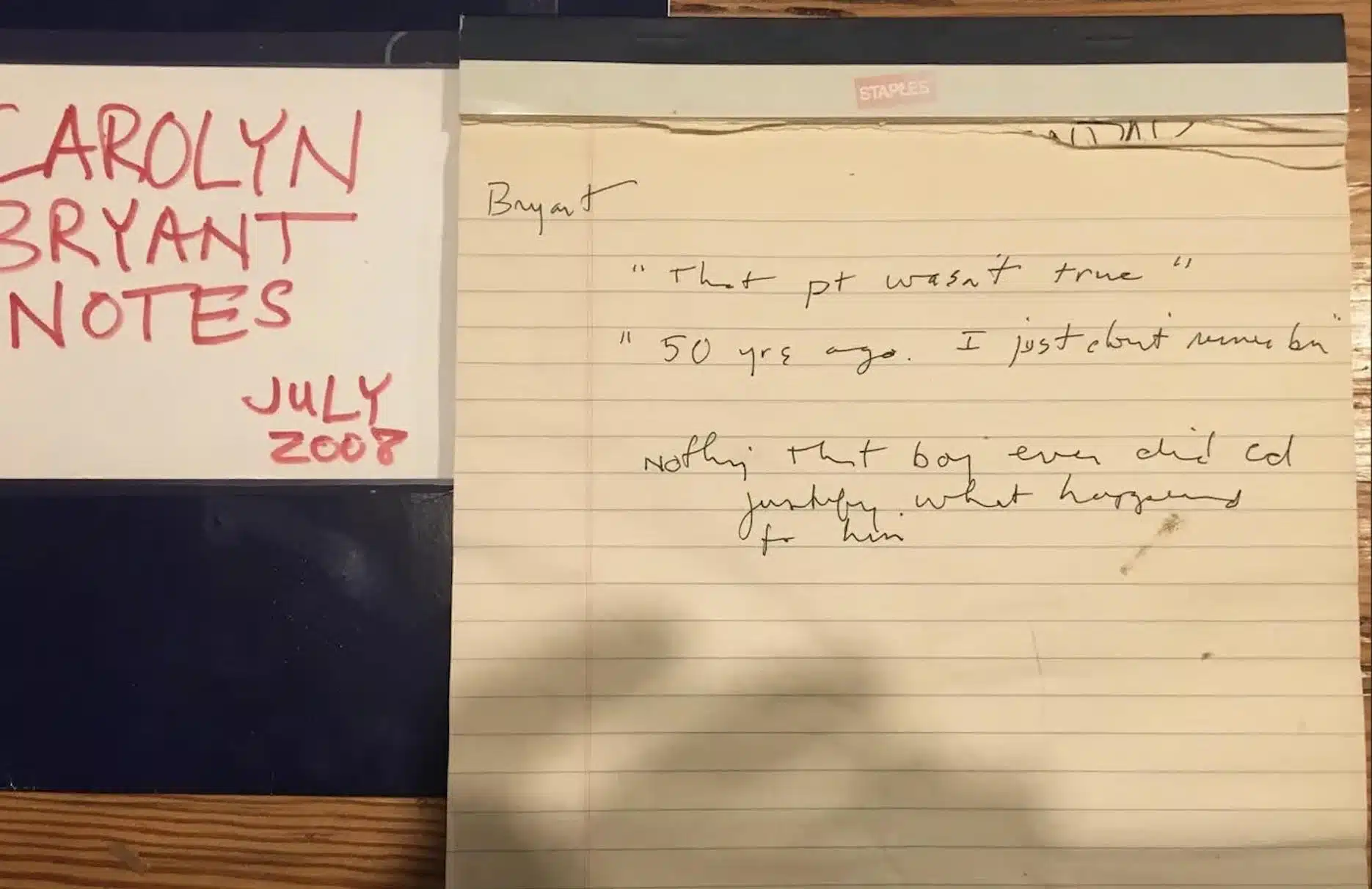

Tyson emailed me a photograph of his undated notes, which he shared with the FBI: “That pt wasn’t true. … 50 yrs ago. I just don’t remember. … Nothing that boy ever did could justify what happened to him.”

The way the quote appears in the “Till” book (italics show the words missing from the notes): “They’re all dead now anyway. … I want to tell you. Honestly, I just don’t remember. It was 50 years ago. You tell these stories for so long that they seem true, but that part is not true. … Nothing that boy ever did could justify what happened to him.”

Tyson told me Donham’s recantation took place in July 2008.

The problem with that date? He hadn’t met her yet, according to emails he wrote in August 2008 to her family.

Asked by email how he could have interviewed Donham in July 2008 when he had yet to meet her then, Tyson did not reply.

Tyson said Bryant didn’t take exception to “any of the facts” in the book, but was upset about people posting pictures of their house on the Internet.

Bryant told me she did object and shared an email with the FBI that she had sent Tyson, wanting to know why he was saying Donham had admitted she lied.

Bryant wrote Donham’s memoir, “I Am More Than a Wolf Whistle: The Story of Carolyn Bryant Donham,” and shared a copy with Tyson, who said in an August 2008 email that the work would prove “invaluable to history.”

Bryant said Tyson agreed to act as an editor for the book — a claim he told me was “bullsh–.”

But emails and edited versions of Donham’s memoir show Tyson edited the book, suggested revisions and rewrote the preface. The Department of Justice’s report also noted Tyson’s editing.

In a note Tyson put at the top of Donham’s memoir on March 6, 2009, he wrote, “Dear Marsha and Carolyn: I am sorry to take so long getting this back to you. I enjoyed reading it. But editing is hard work …

“Read over my edits and comments. I think they may suggest to you some of the broad outlines for another revision. When you finish another version — there will be several more, which is the nature of the publication process — you may feel free to send it to me. … You’ve done a great job thus far.”

He emailed Bryant and asked her to list him as “editor of the final project, since I am a professional scholar who has a boss (the dean) who wants to know how I spent my time and energy. ‘Editor’ can go on my annual report and suggest to the dean that I don’t just sit around and drink coffee and read the newspaper, regardless of what my wife and children might report to the contrary.”

Bryant believes it was “unethical” for him to serve as her editor and then take passages from her book to use in his own publication, she said. “He denied being my editor. It’s pretty damn obvious he was my editor.”

She said she is even angrier that Tyson recently made public a copy of her book, she said. “It appears to me that he is trying to inject himself into the Emmett Till story again by making sure he’s front and center.”

Tyson denied to the FBI that he ever agreed to assist Bryant in getting the memoir published, but in his first email to the family in August 2008, he wrote, “ think you should try to publish this book, and I will be glad to offer what help I can, including introducing you to my agent.”

At no point in Donham’s memoir, the two interviews she gave Tyson or the interviews she gave the FBI does she say she recanted. In fact, in her memoir, she doubled down on the claim that Till attacked her. She even made the head-scratching claim that when Till’s kidnappers asked her if he was the one who attacked her in the store, she refused to say — only for Till to identify himself to his kidnappers.

One of the biggest questions the FBI had for Tyson was why, after Donham recanted, he never asked her to repeat her statement or quiz her about this contradiction. He told the FBI that he didn’t want to interrupt the “flow” of the conversation, but he interrupted her at other times to clarify points, the Justice Department noted in its report closing the Till case.

Tyson had other opportunities in his editing of the memoir. He wrote many suggestions and questions about the book, but he never asked Donham a single question about what he claimed was her recantation.

The FBI asked Tyson why he failed to share this important evidence with authorities for nearly a decade, and he replied that he thought the case was closed.

When investigators interviewed Tyson, “rather than obtaining other corroborating evidence to support Tyson’s claim that … [Donham] offered a recantation,” the report said, “investigators instead identified numerous inconsistencies in Tyson’s account that raised questions about the credibility of his account of the interviews.”

In closing the Till case on Dec. 6, 2021, the Justice Department said, “Tyson’s account lacks credibility,” citing his “shifting explanations to FBI investigators …, the questionable nature of his relationship with [Donham], and his financial motives.”

Sixteen months later, Donham died — and with it any hope of a prosecution in the Till case.

After discovering these things about “The Blood of Emmett Till,” I reached out to a historian, who told me, “You know there were problems with Tyson’s previous book.”

That was news to me. Researcher Brandon Arvesen and I dove deeper into “Blood Done Sign My Name.”

The book centers on the May 11, 1970 killing of Henry Marrow, a 23-year-old Black man killed by members of the Teel family. After his slaying, Robert and Larry Teel turned themselves in to authorities, who moved them from a local jail to a prison in Raleigh 40 miles away, according to newspaper accounts.

The book opens with Tyson claiming his 10-year-old friend, Gerald Teel, told him in person on the evening of May 12, 1970, that his father, Robert, and his brother, Roger, shot “a n—–” last night in Oxford, North Carolina.

One problem with this claim? The Teel family may have already left town for safety reasons to Mount Olive, more than 100 miles away, according to newspaper reports.

The Feb. 21, 1971, Durham Herald-Sun newspaper says Teel’s sons “did not return to school in Oxford after May 11. Instead they were enrolled in classes in Mount Olive where they finished out the term.”

Tyson did not reply to calls and emails regarding this question.

This is far from the only issue with the book. “Name” has some faulty footnotes, wrong details, wrong dates for events and wrong quotations.

For instance, Tyson quoted Black businessman James Gregory as saying, “Even some black folks want to believe we’ve made a lot of progress in race relations, but deep down they know things are bad.”

Tyson attributed the quote to the May 29, 1970, issue of the Raleigh News and Observer. The actual quote from Gregory, published a day earlier, said, “Outsiders are responsible for all of this.”

During their murder trial, Robert and Larry Teel claimed self-defense.

Robert Teel’s stepson, Roger Oakley, became the defense’s surprise witness, claiming he was the one who fired the fatal shot, but accidentally, of course. A jury acquitted the Teels, and a Raleigh News and Observer editorial called the verdict a “sham and mockery.”

Thirteen years later, Tyson interviewed the father, Robert Teel, for a master’s thesis.

The Teel family shared what they say is a handwritten contract that Tyson signed and gave them at the time: “In exchange for above cooperation, Mr. Tyson will, upon graduation from law school, represent Mr. [Robert] Teel as his legal counsel in a legal action of Mr. Teel’s choice, without retainer’s fee, on a 50%/50% contractual basis, … immediately upon graduation to perform above legal action in a prompt manner.” (Tyson has a doctorate in history, but his Duke University biography makes no mention of law school.)

After Tyson wrote “Blood Done Sign My Name,” he donated a copy of his master’s thesis to the Thornton Library in Oxford and said in the author’s note that someone had torn out several pages about Marrow’s killing, “presumably to prevent other people from reading them.”

The thesis has since disappeared from the library, but Mississippi Today has obtained a copy of the entire thesis, including the missing pages, which differs from “Name.”

In his thesis, Tyson wrote that Marrow “walked down to Freeman’s store and returned with a six pack of Country Club Malt Liquor,” but in “Name,” Tyson wrote that Marrow went to Teel’s convenience store to get a big Pepsi and something to eat.

Robert Teel ran a car wash, according to newspaper articles at the time. He also operated a barber shop, a coin-operated laundromat and a cycle shop, according to the Feb. 16, 1971, Oxford Public Ledger. The newspaper mentions nothing about a convenience store, and Teel’s son, Larry, said they never had one.

As with his Till book, Tyson didn’t interview the victim’s family.

When Till’s cousin, Parker, found out that Donham, the white woman at the center of the case, denied she had ever recanted and there was no recording, his heart sank, he said. “It was a blow.”

Tyson “did some big lying,” said Parker, whose book with Chris Benson, “A Few Days Full of Trouble: Revelations on the Journey to Justice for My Cousin and Best Friend, Emmett Till,” was published in January. “He said he had a recorder, but everything is missing.”

Tyson has defended the recantation, telling The New York Times that he took detailed notes: “Carolyn started spilling the beans before I got the recorder going. I documented her words carefully. My reporting is rock solid.”

Till’s cousin, Gordon, said for the author to make things right to the Till family, he would need to apologize for the harm he has caused them. “He would have to admit he fabricated this,” she said.

Tyson did not reply to a request for comment on the Till family’s remarks.

After the release of his Till book in 2017, CBS This Morning interviewed Tyson about the bombshell quote from Donham, whom he suggested had recanted because she was remorseful.

“We’re not punished for our sins; we’re punished by our sins,” he told Gayle King. “Nobody ever gets away with anything.”

Researcher Brandon Arvesen contributed to this report.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Coast judge upholds secrecy in politically charged case. Media appeals ruling.

A Jackson County Chancery Court judge is denying the public access to a case that involves several politically connected Mississippians and their failed venture to ticket uninsured motorists using cameras and artificial intelligence.

Media companies Mississippi Today and the Sun Herald have filed for relief with the state Supreme Court, arguing that Chancery Judge Neil Harris improperly closed the court file without notice and a hearing to consider alternatives. The media outlets say the court file should be opened.

Mississippi Today in June filed its motion asking that Harris unseal the case, which he denied six days later.

Gulfport attorney Henry Laird writes in the media companies’ petition for state Supreme Court review, “The Chancery Court sealing the entire court file both before and after Mississippi Today’s motion to unseal the file violates the public and press’ cherished right of openness and access to its public court system and records.”

Mississippi judges have long followed a 1990 state Supreme Court decision that says, “A hearing must be held in which the press is allowed to intervene on behalf of the public and present argument, if any, against closure.”

Instead, Harris said he found no hearing necessary after reviewing the pleadings to open the file. The case, he said, is between two private companies.

“There are no public entities included as parties,” he wrote, “and there are no public funds at issue. Other than curiosity regarding issues between private parties, there is no public interest involved.”

The case involves what is usually a public function: Issuing tickets to the owners of uninsured vehicles. And, according to one party to the case, the Mississippi Department of Public Safety is owed $345,000 from the uninsured motorist program.

READ MORE: Private business ticketed uninsured Mississippi vehicle owners. Then the program blew up.

Since the entire court file is closed, the public is unable to see why the judge sealed the case. The Mississippians said in the Chancery Court case that they have “substantial” business interests to protect and “a lot of political importance,” an attorney opposing them said in a related federal case that is not sealed.

Georgia-based Securix LLC signed up its first Mississippi client in 2021, the city of Ocean Springs, an agreement with the city showed. Securix developed a program that uses traffic cameras, artificial intelligence and bulk data on insured motorists to identify the owners of vehicles without insurance.

To sign on other Mississippi cities, Securix enlisted three well-known consultants, Quinton Dickerson, Josh Gregory and Robert Wilkinson. Dickerson and Gregory are Republican political operatives in Jackson who have run numerous state and local campaigns and advise many of the state’s top elected officials. Wilkinson, a Coast attorney, has represented local governments and government agencies, including the city of Ocean Springs.

MS business partnership sours

In 2023, the Mississippians formed QJR LLC. Their company entered a 50-50 partnership with Securix called Securix Mississippi.

Securix Mississippi sold the cities of Biloxi, Pearl and Senatobia on the uninsured driver program.

Fees collected from uninsured drivers were apportioned to the company, the cities and the Department of Public Safety, the operating agreement with Biloxi showed.

The citations offered three options, according to copies included in a federal lawsuit filed by three Mississippi residents who received them:

- Call a toll-free number and provide proof of insurance.

- Enter a diversion program that charges a $300 fee and includes a short online course and requires agreement that the vehicle will not be driven uninsured on public roadways.

- Contest the ticket in court and risk $510 in fines and fees, plus the potential of a one-year driver’s license suspension.

The Securix Mississippi partnership soon soured.

Securix Chairman Jonathan Miller of Georgia said in a sworn court declaration submitted in the federal case that he was subjected around March 2024 to a “freeze out” by members and/or employees of QJR. They stopped giving him information, Miller said.

The Department of Public Safety in August pulled the plug on the controversial ticketing program, shutting off the company’s access to the insured driver database.

In September, QJR filed its Chancery Court lawsuit against Securix LLC.

What is known about the case comes from documents in the federal court file. QJR claims the company and its members have been defamed by Miller and Securix and wants their 50-50 business partnership dissolved.

The Chancery Court case does not even show up when the parties are searched for by name.

With a case number gleaned from the federal court file, a search of chancery records shows only that the case is under seal.

Normally, when a case is under seal, the docket would still be available. A docket lists all records and proceedings in a case. While sealed records are listed and described, they can’t be viewed.

“There is no court file,” attorney Laird said in asking the Supreme Court to review Judge Harris’ decision to leave the file sealed. “There is no docket sheet. There is absolutely no access on the part of the public or press to their public court file in this case.”

Judge closes file without public notice

All Mississippi court files are presumed open unless they are closed with notice and a hearing under guidelines established in the 1990 case Gannett River States Publishing Co. vs. Hand.

“It appears that the judge ignored what has been settled law in Mississippi since 1990,” said retired Jackson attorney Leonard Van Slyke, who represented Gannett in the case and still advises the media.

He added, “Since that time, there have not been many efforts to close a courtroom or a court file because the rules are pretty clear as to when that can be done. It is obvious from the rules that this would be a rare occurrence.”

A court file can be closed only if a party in the case requesting closure can show an “overriding interest” that would be prejudiced by publicity.

The Supreme Court said in 1990 that the public is entitled to at least 24 hours’ notice — on the court docket — before a judge considers closure. As a representative of the public, the media has a right to a hearing before a court file or proceeding is closed.

At the hearing, the judge must consider the least restrictive closure possible and reasonable alternatives. The judge also must make findings that explain why alternatives to closure were rejected.

The court wrote in Gannett vs. Hand:

“A transcript of the closure hearing should be made public and if a petition for extraordinary relief concerning a closure order is filed in this Court, it should be accompanied by the transcript, the court’s findings of fact and conclusions of law, and the evidence adduced at the hearing upon which the judge bases the findings and conclusions.”

Because Judge Harris held no hearing, the high court will have a scant record on which to base its review. Without a court record, Laird pointed out in his filing, the public can have no confidence the judge made a sound decision.

Kevin Goldberg, an attorney who serves as vice president and First Amendment expert at the nonpartisan, nonprofit Freedom Forum, said the First Amendment guarantees the public access to courts.

In the Securix case, he said, a private business was doing work normally performed by a police department or other public agency, and residents could be snared into legal proceedings when they received tickets and public funds were involved.

“These are not private people in a small town, going about their business,” Goldberg said. “These people’s business is the public’s business . . . I think that means they need to accept that they’re going to be scrutinized all the time, including when they voluntarily make a decision to go to court.”

This article was produced in partnership between the Sun Herald and Mississippi Today.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Coast judge upholds secrecy in politically charged case. Media appeals ruling. appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article maintains a largely factual and investigative tone, focusing on government transparency, judicial procedure, and public access to court records. It critiques the secrecy upheld by a judge in a politically sensitive case involving private companies executing public functions, highlighting concerns about accountability and public interest. The framing leans slightly toward advocating for open government and media rights, values often associated with center-left perspectives. However, it stops short of overt ideological framing or partisan language, striving to report the facts and legal context while underscoring the public’s right to scrutiny.

Mississippi Today

Why Andy Gipson is running for governor

Republican Andy Gipson, the first candidate to publicly announce a run for Mississippi governor in 2027, outlines his five-plank platform. No. 1 is fighting crime, which Gipson says is rising in what were once quiet rural areas, because “If people don’t feel safe, nothing else matters.” He also offers a brief sampling of his baritone crooning from his just-released two studio albums.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Why Andy Gipson is running for governor appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Mississippi Today

‘Will you trust us?’: JPS plan for stricter cellphone policy makes some parents anxious

Superintendent Errick Greene wanted to be very clear with the roughly 50 parents who attended Thursday night’s community listening session: Jackson Public Schools already has a policy banning students from using cellphones at school.

But the leadership of Mississippi’s third-largest school district has decided that a new approach is in order, citing a series of incidents in recent years involving students using their cellphones to bully others, organize fights or text their parents inaccurate information about violence happening at or near their school.

“To be clear, it’s not the majority of our scholars, but I can’t look at a class and know who’s gonna be bullying today, who’s gonna be scheduling a meetup to cut up today,” Greene said toward the end of the hour-long meeting held at the JPS board room. “I can’t look at a group of scholars and say, ‘OK, yeah, you’re the one, let me take your phone, the rest of you can keep it.’”

Under the rewritten policy, students who take their phone out of their backpacks during the instructional day will lose it for five days for the first infraction, 10 days for the second and 45 days for the third. Currently, the longest the school will hold a phone is 10 days.

The Jackson school board is expected to consider the new policy at its meeting next week and the district hopes to implement the change when the new school year starts later this month, said Sherwin Johnson, the district’s communications director.

Students also currently have the option to pay up to a $25 fine to get their phone back, but the district wants to rescind that aspect of the policy.

“We’ve discovered that’s not equitable,” said Larrisa Harris, the JPS general counsel. “Not everybody has the resources to come and pay the fine.”

Support for the new policy among the parents who spoke at the listening session varied, but all had questions. How will students access the internet on their laptops if the WiFi is spotty at their school and they need to use their cellphone hotspot? If students are required to keep their phones in their backpacks during lunch, how will teachers prevent stealing? How will JPS enforce the ban on using cellphones on the bus?

One mother said she watches her daughter’s location while she rides the bus to Jim Hill High School so she knows her daughter made it safely.

“If they can’t have it on the bus, who’s gonna enforce that?” she said. “I’m just gonna be real, the bus driver got to drive.”

A common theme among parents was anxiety at the prospect of losing direct contact with their kids in the event of an emergency. A Pew Research survey found that most adults, regardless of political affiliation, support cellphone bans in middle and high school classes. But those who don’t say it’s because their child can use their phone during emergencies.

“If something happened, will we get an automatic alert to notify us? Because a lot of the time we see things on social media first,” said Ashley McIntyre, a mother of three JPS students. She attended the meeting with her eldest daughter, Aaliyah, who recently graduated from Powell Middle School.

Though JPS does have an alert system for parents, McIntyre said she didn’t know if it existed. She cited a bomb threat at Powell last year that she found out about because Aaliyah texted her, not through a school alert.

“We didn’t know what was going on, and she texted me, ‘Mom, I’m scared,’ so I went up there,” McIntyre said. “So that puts us on edge.”

Aaliyah said she uses her phone to text her mom and watch TikTok, but she feels like her classmates use their phones to be popular or to fit in. When a fight happens, she said many students pull out their phones to record instead of trying to get an adult who can stop it. Then the videos end up on Instagram pages dedicated to posting fights in JPS.

“Once the principal found out about the fight pages, they came around looking inside our videos and camera rolls,” she said. “It happened to me last year. They thought I had a fight on my phone.”

Toward the end of the meeting, Laketia Marshall-Thomas, the assistant superintendent for high schools, took the mic to respond to one parent who said she was concerned that older students would not come to school if they knew their phone could be taken.

“What we have seen is, it’s the older students—” Marshall-Thomas began.

“They are the problem,” someone from the audience chimed in.

“We’re not saying they cannot have them,” she continued. “We know that they have after school activities and they need to communicate with their moms … but we have had major, major issues with cellphones and issues that have even resulted in criminal outcomes for our scholars, but most importantly, our students … have experienced a lot of learning loss.”

While the district leadership did not go into detail about the criminal incidents, several pointed to instances where students have texted their parents inaccurate information, such as an unsubstantiated rumor there was a gun during a fight at Callaway High School or that a shooting outside Whitten Middle School occurred on school property.

“Having phones actually creates far more chaos than they help anyone,” Greene said.

While cellphones have been banned to varying degrees in U.S. schools for decades, youth mental health concerns have renewed interest in more widespread bans across the country. Cellphone and social media usage among school-aged kids is linked to negative mental health outcomes and instances of cyberbullying, research shows.

At least 11 states restrict or ban cellphone use in schools. After Mississippi’s youth mental health task force recommended that all school districts implement policies that limited cellphone and social media usage in classrooms, a bill that would’ve required school boards to create cellphone policies died during the legislative session. Still, several Mississippi school districts have passed their own policies, including Marshall County and Madison County.

Another concern about the ban was a belief among a couple of speakers at the meeting that cellphones can help parents hold the district accountable for misdeeds it may want to hide.

“I just saw a video today. It was not in JPS, but it was a child being yelled at by the teacher and had he not recorded it, his momma would have never known that this sweet lady that they go to church with is degrading her child like that,” one mother said.

Statements like these prompted responses from teachers and other parents who urged the skeptical attendees to be more trusting or to make sure the district has updated contact information for them in case school officials need to reach parents during an emergency.

“I think we have to trust the people watching over our children,” said one of the few fathers who spoke. “When I grew up, what the teacher said was gold.”

One teacher asked the audience, “Will you trust us?”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post ‘Will you trust us?’: JPS plan for stricter cellphone policy makes some parents anxious appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

The article presents a balanced report on Jackson Public Schools’ proposed stricter cellphone policy without taking a clear ideological stance. It fairly conveys the perspectives of school officials emphasizing discipline and safety, alongside parental concerns about communication and emergency access. The tone remains neutral, focusing on factual details such as policy changes, reasons behind them, and community reactions. While it includes some skepticism from parents and responses from district staff, the language does not endorse or oppose either side. Overall, the coverage adheres to neutral, factual reporting by presenting multiple viewpoints without editorializing.

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed6 days ago

Learning loss after Helene in Western NC school districts

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed6 days ago

Turns out, Medicaid was for us

-

Local News7 days ago

“Gulfport Rising” vision introduced to Gulfport School District which includes plan for on-site Football Field!

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

The Bayeux Tapestry will be displayed in the UK for the first time in nearly 1,000 years

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed7 days ago

With brand new members, Louisiana board votes to oust local lead public defenders

-

Mississippi Today4 days ago

Hospitals see danger in Medicaid spending cuts

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days ago

As floods recede, Kerrville confronts the devastation

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

Arkansas Department of Education creates searchable child care provider database