Mississippi Today

‘System of privilege’: How well-connected students get Mississippi State’s best dorms

Mississippi State University’s housing department has a confidential practice of helping certain well-connected students secure spots in its newest and most expensive dorms, while the premium price tag pushes many less privileged students into the campus’s older, cheaper halls.

It starts when donors, public officials, legacy alumni or other friends of the institution make a request for what the university calls “housing assignment assistance.”

Then, the Department of Housing and Residence Life works to place these students in the dorms they desire.

The practice is not an official university policy, and it’s not advertised on Mississippi State’s website. But inside the housing department, it is institutionalized. Many full-time staff refer to the process by the phrase “five star,” a reference to the euphemistic code — 5* — the department used to assign well-connected students in its housing database, documents show.

In recent years, the department changed the process to make it more internal. 5* has remained a virtual secret on campus — until now.

That’s partly because the department’s leadership has worked to keep the process under wraps, even going so far as to explicitly tell staff not to share information about 5* outside of the department, according to emails Mississippi Today obtained through a public records request.

“Family business reminder – We/you don’t air to others,” Dei Allard, the department’s executive director, wrote in an email four years ago to high-up staff in the department. “Basically, only a handful of those within our organization should be privileged to have this information… i.e. keep your mouth shut.”

In response, one staff member noted that processes like this likely exist at universities across the country, while another raised concerns that 5* results in students receiving preferential treatment, such as a better room assignment or a new room if they aren’t satisfied with their initial draw, because of who they know.

“The name itself is an issue in my opinion,” wrote Jessica Brown, the department’s assignments coordinator at the time. “I think this has created a very unfair system and a system of privilege. I think that it in a way causes other students to be unknowingly discriminated against such as based on their economic social status.”

The university did not grant an interview to Mississippi Today about the 5* practice. Allard declined to provide more information beyond the university’s official response.

Through written statements, a spokesperson denied the process results in better treatment of well-connected students, referring to 5* as a form of assistance the department works to provide to all types of students.

“There is a long-standing broad administrative practice of providing assignment assistance to those students who request it when that’s possible by price point and housing availability to do so,” Sid Salter, the university’s vice president for strategic communications, wrote in response to Mississippi Today’s questions and findings.

Nevertheless, Salter did not deny the housing department uses the term 5* to refer to the practice and the students who benefit from it. He acknowledged the housing department sets aside about 120 beds for 5* students each year and confirmed which dorms they typically request — Magnolia, Moseley, Oak, Dogwood and Deavenport halls. And, Salter was able to estimate that the department has helped roughly 100 5* students each year, who are mostly white and wealthier.

“Not exclusively correct, but generally so,” Salter wrote. “We certainly have received housing assignment requests from non-white students.”

The university does not know when the 5* designation started, Salter wrote, only that it predates the beginning of Mark Keenum’s presidency in 2009 and began as a response to requests “from legacy (multi-generational) alumni, university donors, university partners, institutional friends, public officials and others who asked for help.”

Though emails obtained by Mississippi Today do not reflect that staff who were familiar with the process thought 5* students received the label based on academics, Salter wrote the practice has also been used to recruit “academic stars” who tie their enrollment to housing preferences such as location, cost, amenities and affinity groups.

“Why would any university not be responsive to such requests if possible?” Salter wrote.

A different housing assignment process exists for student athletes or those with certain scholarships like the Luckyday Scholars Program for students who are community leaders.

At one point, the process of helping 5* students land in their preferred dorm appeared to include a system for labeling these students in the university’s housing database. The department had what appears to be instructions for how to assign the status to the housing application profiles “for each 5 star and roommate of a 5 star,” according to an unlabeled document obtained by Mississippi Today.

That document is no longer used, and the department does not know when it was created. Salter wrote that housing no longer uses the 5* label in its database and does not keep a separate list of 5* students.

Mississippi State believes the practice is widespread at similar universities across the state and country, Salter wrote, adding the university “is curious why we are being singled out among Mississippi institutions when significant housing issues are in the headlines at other state schools.”

Unfairness exists in the dorms at universities across the country, experts say. That could look like a wealthy parent who knows how to pull strings for their students or a dorm that is priced too high for lower-income students.

“It’s not just a Mississippi thing,” said Elizabeth Armstrong, a University of Michigan sociology professor whose 2015 book, “Paying for the Party”, examined the different experiences students have in college, including in the dorms, based on their socioeconomic class.

Still, Armstrong said she had never heard of a process as blatant as Mississippi State’s, which she described as tipping the scale in favor of privileged students who are already more likely to be able to live in the priciest dorms because their families can afford to foot the bill.

“The sense they are trying to keep it a secret suggests they know this is something they shouldn’t be doing,” she said.

Emails show housing department staff believed the 5* practice meant preferential treatment

No issues with the 5* process have been raised to the administration, Salter wrote.

But emails obtained by Mississippi Today show housing department staff who were involved in the process had concerns or at least knew the practice troubled their employees.

In June 2020, Allard, who had been the executive director since 2017, asked her staff to describe the 5* process in the same email where she cautioned them against sharing information about it outside the department.

The request came at a salient time: Colleges across the country were issuing statements in support of diversity, equity and inclusion amid the George Floyd protests. Days earlier, thousands had gathered in Jackson in one of the state’s largest protests against racial inequities since the civil rights movement.

The responses, which are reprinted here without correction, show what staff on the ground understood the 5* status to mean: Better room assignments and help for VIP students with room changes and other housing issues.

“I’m not quite sure what the true definition is but from my understand it is students that we adjust based on the wants or needs of the President’s Office,” wrote Brown, who is no longer with the university.

But the 5* students themselves were starting to push the practice beyond its original intent to things like room changes, Brown continued.

“I think they know that they have this privilege,” she wrote, “and this is why the process is starting to go further than just a better room assignment.”

Brown noted it was not up to staff to change the practice.

“Honestly I am not sure how this issue can be fixed,” Brown wrote. “I think that this issue has to be fixed starting from a higher executive level (outside of housing), but I am not sure if they are willing to do that.”

Danté Hill, the then-associate director of occupancy management and residential education, had a different perspective.

“I’m sure all campuses have some type of VIP resident,” wrote Hill, who is now the department’s facilities and maintenance director. “It is just the nature to the political structure that is in place. I have not verified this with many campuses however.”

Hill wrote that he did not feel that 5*s received special treatment, but his staff felt their decisions were overturned in instances involving those students. With access to the university’s housing database, they could see which students had the 5* status.

“They do not see these students as a representative population,” he wrote. “They see these overall as privileged students not usually of color. I think this group is more honed in on inclusion and SJ (social justice) and wants to see fair treatment across the board and they see this process as the ability to allow a student whose family has some kind of connection to move in front of students who may have done everything the right way.”

Hill thought it would help if the department stopped using the label.

“I believe we may need to remove the classification and make this process more internal and not label these students as anything in particular,” he wrote. “I don’t know how we do this other than keeping emails on file when we place someone.”

University will continue 5* practice

Mississippi State’s new construction dorms are already more likely to house wealthier and well-connected students in part because they can cost nearly $4,000 more than the campus’ traditional dorms, the seven residence halls built before 2005.

The 5* practice contributes to the inequity, Armstrong said.

“It’s kind of like putting an extra thumb on the scale when the thumb is already way on the scale,” she said.

It also means the traditional dorms are more likely to house lower-income students. Mollie Brothers, a resident advisor during the 2020-21 school year, observed this when she oversaw Critz Hall, one of the university’s traditional-style dorms that was built in the 1950s and renovated in 2001.

More than half of the women on her floor were Black, she recalled, while her friends who worked in the new construction dorms oversaw floors that were almost entirely white.

“In the other dorms that weren’t as nice, it was definitely more diverse,” Brothers said.

Salter said the university does not have metrics to support this claim.

The university knows it has a shortage of new construction housing and is working to provide more options with the construction of Azalea Hall, a new dorm the university plans to open ahead of fall 2025 that will feature single rooms and restaurants, according to a press release.

But if history is an indication, when freshman start applying for a room in Azalea Hall, it follows that 5*s would have an advantage, which the university did not deny.

“In this particular facility, Lucky Day Scholars will have primary preference, but we believe Azalea will be an extremely popular housing option,” Salter wrote.

After Allard’s email, the university made changes to its 5* practice — it stopped notifying RAs which students on their floor were receiving housing assistance, therefore reducing the number of people who know about the status. Around the same time, the university also stopped applying the 5* status to student profiles in its housing database, Salter wrote.

But Mississippi State said it would continue the practice.

Salter provided a statement from Regina Hyatt, the vice president for student affairs, who said the department’s housing policies are compliant with best practices and state and federal law.

“MSU works hard to assist all students who ask for help in the process, including students at every point on the socioeconomic continuum,” Hyatt said. “We will continue that practice as it (has) historically been part of our university’s traditions.”

Do you have insights into Mississippi State’s 5* process? Help us report.

Our investigation uncovered Mississippi State’s institutionalized practice of helping well-connected students land spots in the university’s newest and best dorms. But there’s more to report: When did the 5* practice start, who started it, and why? Once 5* students are in the dorms, what kind of additional support does the Department of Housing and Residence Life provide? How are less-connected students affected by the 5* practice?

Help us continue our reporting by filling out the form below. We are gathering this information for the purpose of reporting, and we appreciate any information you can share. We protect our sources and will contact you if we wish to publish any part of your story.

(function (c, i, t, y, z, e, n, x) { x = c.createElement(y), n = c.getElementsByTagName(y)[0]; x.async = 1; x.src = t; n.parentNode.insertBefore(x, n); })(document, window, “//publicinput.com/Link?embedId=73322”, “script”);

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1857

March 6, 1857

In Dred Scott v. Sandford, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld slavery in a 7-2 vote.

Dred Scott and his family were enslaved, and when he tried to purchase their freedom, they were refused. He and his wife, Harriet, each filed separate lawsuits, calling for their freedom. They noted that they had lived for years in both free states and free territories.

A jury ruled in favor of Scott and his family. But on appeal, the Supreme Court ruled that Black Americans, whether slave or free, had no right to sue.

In a stinging dissent, Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis wrote that the claim Black Americans could not be citizens was baseless: “At the time of the ratification of the Articles of Confederation, all free native-born inhabitants of the States of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and North Carolina, though descended from African slaves, were not only citizens of those States, but such of them as had the other necessary qualifications possessed the franchise of electors, on equal terms with other citizens.”

He noted that the Declaration of Independence didn’t say that “the Creator of all men had endowed the white race, exclusively with the great natural rights.

” The decision drew wrath from many, including future President Abraham Lincoln, who called it “erroneous.” Two months later, Scott won his freedom when the sons of his first owner, Peter Blow, purchased his emancipation, setting off celebrations in the North.

The court decision helped lead to the Civil War, and the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments were adopted to counter the ruling. In 2017, on the 160th Anniversary of the Dred Scott decision, the great-great-grandnephew of Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney apologized to Scott’s great-great-granddaughter and all Black Americans “for the terrible injustice of the Dred Scott decision.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

Legislation to license midwives dies in the Senate after making historic headway

A bill to license and regulate professional midwifery died on the calendar without a vote after Public Health Chair Hob Bryan, D-Amory, did not bring it up in committee before the deadline Tuesday night.

Bryan said he didn’t take the legislation up this year because he’s not in favor of encouraging midwives to handle births independently from OB-GYNs – even though they already do, and keeping them unlicensed makes it easier for untrained midwives to practice. The proposed legislation would create stricter standards around who can call themselves a midwife – but Bryan doesn’t want to pass legislation recognizing the group at all.

“I don’t wish to encourage that activity,” he told Mississippi Today.

Midwifery is one of the oldest professions in the world.

Proponents of the legislation say it would legitimize the profession, create a clear pathway toward midwifery in Mississippi, and increase the number of midwives in a state riddled with maternity health care deserts.

Opponents of the proposal exist on either end of the spectrum. Some think it does too much and limits the freedom of those currently practicing as midwives in the state, while others say it doesn’t do enough to regulate the profession or protect the public.

The bill, authored by Rep. Dana McLean, R-Columbus, made it further than it has in years past, passing the full House mid-February.

As it stands, Mississippi is one of 13 states that has no regulations around professional midwifery – a freedom that hasn’t benefited midwives or mothers, advocates say.

Tanya Smith-Johnson is a midwife on the board of Better Birth Mississippi, a group advocating for licensure.

“Consumers should be able to birth wherever they want and with whom they want – but they should know who is a midwife and who isn’t,” Smith-Johnson said. “… It’s hard for a midwife to be sustainable here … What is the standard of how much midwifery can cost if anyone and everyone can say they’re a midwife?”

There are some midwives — though it isn’t clear there are many — who do not favor licensure.

One such midwife posted in a private Facebook group lamenting the legislation, which would make it illegal for her to continue to practice under the title “midwife” without undergoing the required training and certification decided by the board.

On the other end of the spectrum, among those who think the bill doesn’t go far enough in regulating midwives, is Getty Israel, founder of community health clinic Sisters in Birth – though she said she would rather have seen the bill amended than killed. Israel wanted the bill to be amended in several ways, including to mandate midwives pay for professional liability insurance, which it did not.

“As a public health expert, I support licensing and regulating all health care providers, including direct entry midwives, who are providing care for the most vulnerable population, pregnant women,” she said. “To that end, direct entry midwives should be required to carry professional liability insurance, as are certified nurse midwives, to protect ill-informed consumers.”

The longer Mississippi midwives go without licensure, the closer they get to being regulated by doctors who don’t have midwives’ best interests in mind.

That’s part of why the group Better Birth felt an urgency in getting legislation passed this year.

“I think there’s just been more iffy situations happening in the state, and it’s caused the midwives to realize that if we don’t do something now, it’s going to get done for us,” said Erin Raftery, president of the group.

Raftery says she was inspired to see the bill make headway this year after not making it out of committee several years in a row.

“We are hopeful that next year this bill will pass and open doors that improve outcomes in our state,” she said. “Mississippi families deserve safe, competent community midwifery care.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

New Mississippi legislative maps head to court for approval despite DeSoto lawmakers’ objections

Voters from 15 Mississippi legislative districts will decide special elections this November, if a federal court approves two redistricting maps that lawmakers approved on Wednesday.

The Legislature passed House and Senate redistricting maps, over the objections of some Democrats and DeSoto County lawmakers. The map creates a majority-Black House district in Chickasaw County and creates two new majority-Black Senate districts in DeSoto and Lamar counties.

“What I did was fair and something we all thought the courts would approve,” Senate President Pro Tempore Dean Kirby told Mississippi Today on the Senate plan.

Even though legislative elections were held in 2023, lawmakers have to tweak some districts because a three-judge federal panel determined last year that the Legislature violated federal law by not creating enough Black-majority districts when it redrew districts in 2022.

The Senate plan creates one new majority-Black district each in DeSoto County and the Hattiesburg area, with no incumbent senator in either district. To account for this, the plan also pits two incumbents against each other in northwest Mississippi.

READ MORE: See the proposed new Mississippi legislative districts here.

The proposal puts Sen. Michael McLendon, a Republican from Hernando, who is white, and Sen. Reginald Jackson, a Democrat from Marks, who is Black, in the same district. The redrawn district contains a Black voting-age population of 52.4% and includes portions of DeSoto, Tunica, Quitman and Coahoma counties.

McLendon has vehemently opposed the plan, said the process for drawing a new map wasn’t transparent and said Senate leaders selectively drew certain districts to protect senators who are key allies.

McLendon proposed an alternative map for the DeSoto County area and is frustrated that Senate leaders did not run analytical tests on it like they did on the plan the Senate leadership proposed.

“I would love to have my map vetted along with the other map to compare apples to apples,” McLendon said. “I would love for someone to say, ‘No, it’s not good’ or ‘Yes, it passes muster.’”

Kirby said McLendon’s assertions are not factual and he only tried to “protect all the senators” he could.

The Senate plan has also drawn criticism from some House members and from DeSoto County leaders.

Rep. Dan Eubanks, a Republican from Walls, said he was concerned with the large geographical size of the revised northwest district and believes a Senator would be unable to represent the area adequately.

“Let’s say somebody down further into that district gets elected, DeSoto County is worried it won’t get the representation it wants,” Eubanks said. “And if somebody gets elected in DeSoto County, the Delta is worried that it won’t get the representation it wants and needs.”

The DeSoto County Board of Supervisors on Tuesday published a statement on social media saying it had hired outside counsel to pursue legal options related to the Senate redistricting plan.

Robert Foster, a former House member and current DeSoto County supervisor, declined comment on what the board intended to do. Still, he said several citizens and business leaders in DeSoto County were unhappy with the Senate plan.

House Elections Chairman Noah Sanford, a Republican from Collins, presented the Senate plan on the House floor and said he opposed it because Senate leaders did not listen to his concerns over how it redrew Senate districts in Covington County, his home district.

“They had no interest in talking to me, they had no interest in hearing my concerns about my county whatsoever, and I’m the one expected to present it,” Sanford said. “Now that is a lack of professional courtesy, and it’s a lack of personal respect to me.”

Kirby said House leaders were responsible for redrawing the House plan and Senate leaders were responsible for redrawing the Senate districts, which has historically been the custom.

“I had to do what was best for the Senate and what I thought was pass the court,” Kirby said.

The court ordered the Legislature to tweak only one House district, so it had fewer objections among lawmakers. Legislators voted to redraw five districts in north Mississippi and made the House district in Chickasaw County a majority-Black district.

Under the legislation, the qualifying period for new elections would run from May 19 to May 30. The primaries would be held on August 5, with a potential primary runoff on Sept. 2 and the general election on Nov, 4.

It’s unclear when the federal panel will review the maps, but it ordered attorneys representing the state to notify them once the lawmakers had proposed a new map.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed1 day ago

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed1 day agoRemarkable Woman 2024: What Dawn Bradley-Fletcher has been up to over the year

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed4 days ago4 killed, 1 hurt in crash after car attempts to overtake another in Orange County, troopers say

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days ago

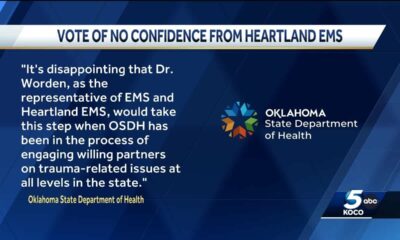

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days agoOklahoma Department State Department of Health hit with no confidence vote

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed6 days agoStorm chances Wednesday, rollercoaster temperatures this weekend

-

Mississippi Today4 days ago

Mississippi Today4 days agoJudge’s ruling gives Legislature permission to meet behind closed doors

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed5 days agoBeautiful grilling weather in Arkansas

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed7 days agoWarner Bros. demands removal of Chickasha's iconic leg lamp

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed3 days agoProbation ends in termination for Va. FEMA worker caught in mass layoffs