Mississippi Today

‘So medieval’: Man with mental illness jailed for 20 days without charges

In January, the head of Mississippi’s Department of Mental Health told lawmakers that people who aren’t charged with a crime are spending less time in jail than they used to: The average wait time for a state hospital bed was down to three days after a court hearing.

At that moment, a young man was on his 16th day locked in the DeSoto County Jail with no criminal charges. He was waiting for mental health treatment.

His mother, Sarah, was still trying to understand why he was there at all.

David, 29, was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder about a decade ago. Since then, he has cycled through hospital stays and group homes. Sarah can rattle off the low points. There was the time her son was walking in the street and got hit by a car and broke his neck. And the time he called her from a Megabus in Texas, nearly at the border with Mexico.

But this was something new: a three-week detention that began after he called 911 seeking treatment and eventually wound up jailed at the request of his providers.

Her son’s treatment in DeSoto County – where a county website still uses the phrase “lunacy” hearings to refer to the proceedings where judges order people like David to receive psychiatric treatment – reminded Sarah of a different era.

“When they, you know, lock them in the dungeon or whatever and put chains on them and just let them live the rest of their lives there,” she said. “This is so medieval, what they’re doing.”

In the end, David was jailed for a total of three weeks before being transported to North Mississippi State Hospital at the end of January. Mississippi Today is not using his or his family’s real names to protect his privacy.

It is far from unusual in Mississippi and particularly in DeSoto County for people to be jailed solely because they are awaiting treatment through the state’s involuntary commitment process. No other state jails so many people for such lengths of time, solely on the basis of mental illness. Mississippi Today and ProPublica previously reported that hundreds of people are jailed without criminal charges every year while they await evaluations and treatment through the involuntary commitment process.

From 2019 through 2022, DeSoto County jailed people without criminal charges just under 500 times, more than any other county in the news organizations’ analysis.

As lawmakers debate changing Mississippi’s commitment laws to reduce jail detentions, David’s path through the state’s mental health system shows how it can funnel a sick person into jail, and how long it can take for them to get out once locked up.

A publicly funded facility established to treat people in crisis sent David to jail. Though the Department of Mental Health says commitment hearings should take place within 10 days, county officials instead kept him locked up for 14 days before he saw a judge, as winter weather shut down the county court system. The state hospital where the judge ordered him to receive treatment would not admit him for six more days – all of which he spent in jail.

The county is working on opening a crisis center to treat people suffering mental health crises – and keep them out of jail during the commitment process – and supervisors recently voted to hire an architect to draw up renovation plans for the county building that will house the center. The county is currently the largest in the state without one.

County administrator Vanessa Lynchard noted that reforming the commitment process is a priority for the Legislature this year, and that could hopefully bring some relief.

“Nobody likes mental commitments in the jail,” she said.

But officials involved in the process say jail is sometimes the only place they have to detain people during the commitment process, and that jailing people is safer than sending them home. And so every year, the county jails well over 100 people solely because they may be mentally ill – including people like David.

‘He really wants to live a normal life’

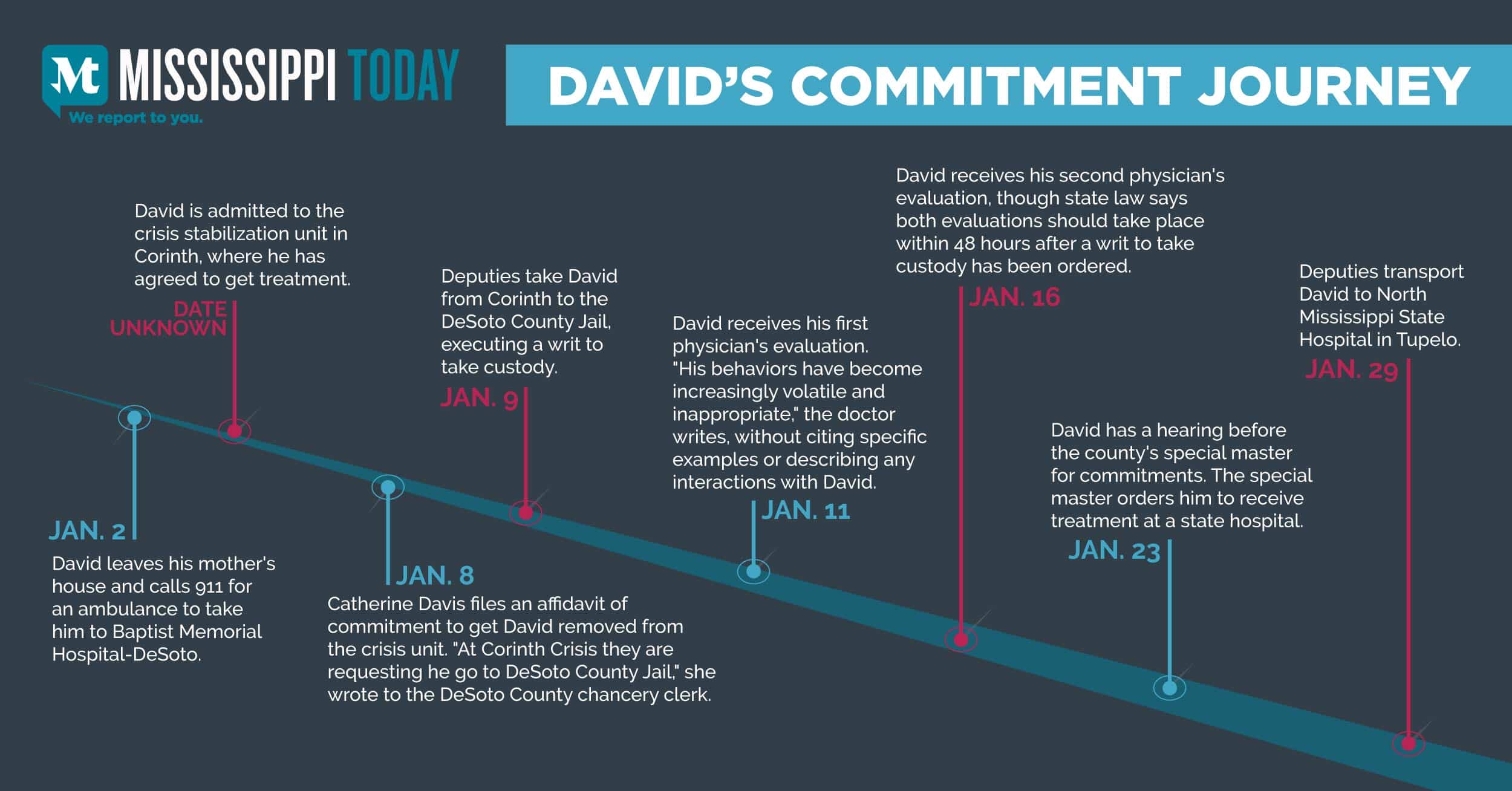

In early January, David walked away from his mother’s home in a tidy subdivision in DeSoto County. He knocked on a neighbor’s door and used the phone to call 911 for an ambulance to take him to the hospital.

When Sarah found out he was at Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto, she decided to let him stay there and get treatment. That he had been able to get himself there was a sign of progress. When his mental illness became severe about 10 years ago, “he used to just let himself spin out of control,” Sarah said.

When David was a teenager, he developed phobias that his mother found strange. He stopped wanting to go to school, claiming his breath smelled bad. After he ran away from home, he was hospitalized at Lakeside, a psychiatric hospital in Memphis.

He graduated from high school and got a job working at a warehouse, riding his bicycle more than an hour each way to arrive by 5 or 6 o’clock in the morning.

Then, when he was about 19, “stuff went totally to the left with him,” his mother said. He would disappear from home for days at a time. If he wound up at a hospital, staff wouldn’t tell her he was there, citing patient privacy protections. At home, he would refuse to take medications.

A few years ago, Sarah spent $2,500 to go through the legal process to gain conservatorship over her son so that she would always be included in conversations about his treatment.

“When the dust settles and the smoke clears, he always comes back to me,” she said. “If you’ve got him and put him on the wrong medication and overmedicated him, then I’ve got to help him get back on track.”

David belongs to a tight-knit family: He has siblings, a doting grandfather, aunts and uncles. Sarah’s phone is full of pictures of her son. There’s a shot of him getting his face painted at a family party and another of him wearing a Mickey Mouse t-shirt at Disneyland. A video shows him chasing his sister’s kids around his mother’s backyard.

His family tries to help him manage his symptoms. When he lived with his older sister Beth recently, he would go into the backyard to pace and talk to himself.

“I’d go out there like every 15 minutes, like, ‘Hey, you’re too loud, you need to calm down,’ but I don’t interrupt,” she said. “That’s his way of calming himself down.”

David has told his sister that he doesn’t like depending on her and their mom, that he feels bad he doesn’t drive or hold a job – something that has been a goal for years.

“He’ll tell you that he really wants to live a normal life,” Beth said.

From the crisis unit to a jail cell

One day in January, after a few days at Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto, David was transported to a crisis stabilization unit in Corinth, where he had agreed to get treatment. Operated by the community mental health center Region IV, which serves residents of DeSoto and four other counties, the facility is one of more than a dozen around the state designed to serve people closer to their homes, ideally keeping them out of the state hospitals – and out of jail.

For David, the crisis unit did the opposite.

Sarah sent over her conservatorship paperwork so she could be updated about his treatment. She expected to hear from her son not long after he arrived there, because he always calls her once he feels more like himself. When that didn’t happen, she called the crisis unit.

“He’s in the DeSoto County Jail,” staff told her.

Documents filed with the DeSoto County Chancery Court and reviewed by Mississippi Today show that after refusing medications twice, David had taken them and said he thought it was helping. There were no indications of violence or physical aggression. But not long after he arrived, staff requested a writ – a document allowing the sheriff’s department to take custody of a patient – because of his “agitation and inappropriate sexual conduct.”

Staff reported that he was experiencing “Psychosis including delusions, irritability. He is continually masterbating (sic).” They wrote that he had masturbated in front of other patients and a staff member.

It’s not clear from the documents exactly how long David was at the crisis unit before staff requested the writ, and Sarah said she was not contacted when he arrived there. It may have been as little as a day or two: The court order committing him says he arrived at Corinth “on or about 01/08/24.”

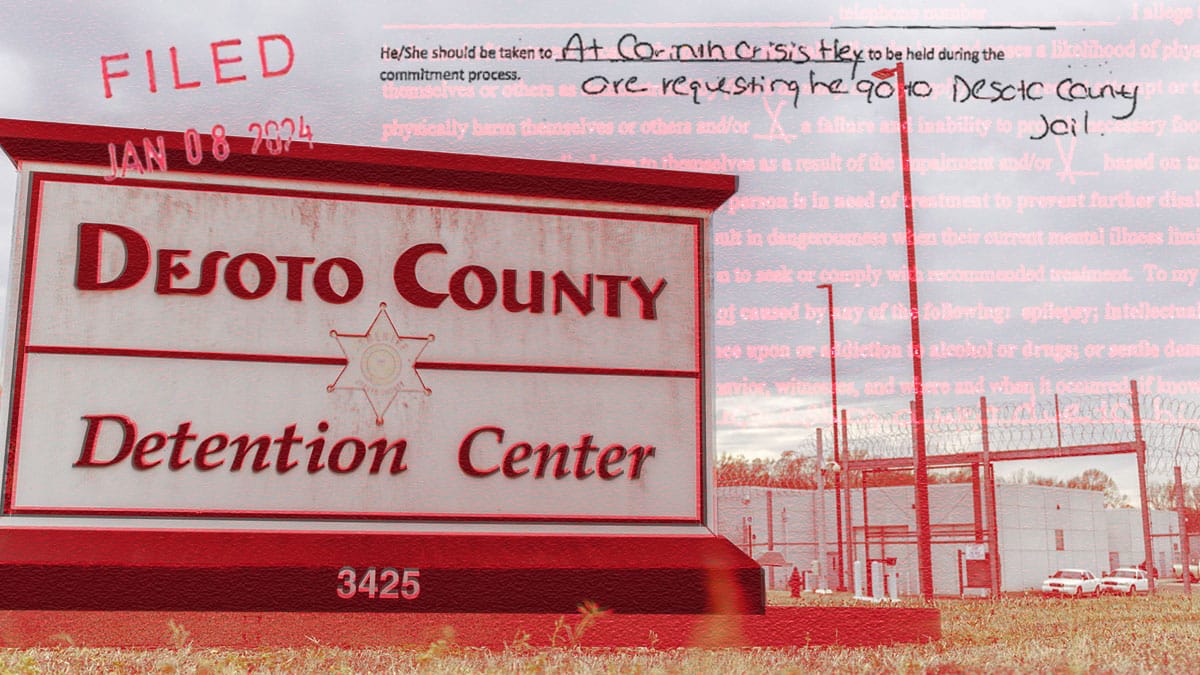

On Jan. 8, Catherine Davis, crisis coordinator at Region IV, which runs the crisis center, wrote: “At Corinth Crisis they are requesting he go to DeSoto County Jail.”

The next afternoon, deputies arrived to take David into custody and drive him 90 minutes back to DeSoto County. He was booked into the county jail with his charge listed as “Writ to take custody.”

Psychiatrists told Mississippi Today that people with David’s condition may exhibit sexually inappropriate behavior like public masturbation, stepping from hypersexuality and impulsivity that can be symptoms of mania.

“All they want to focus on is what he was doing wrong there,” Sarah said. “I understand that. But that’s because he needs psychiatric treatment. He’s mentally unstable. You’re a crisis center. Isn’t that what you do? But instead you ship him off to jail.”

Jason Ramey, executive director of Region IV, the community mental health center that runs the crisis unit, said he can’t discuss a specific client, citing HIPAA.

“At no point in time is it our goal to have somebody sitting in jail, but we also have to think about the wellbeing of the whole CSU, whether it’s the other clients there and things like that,” he said.

Ramey said that in 2023, the crisis unit staff initiated commitment proceedings on only three patients. The facility treated nearly 300 people in the most recent fiscal year.

“We want them to continue to receive treatment,” he said of patients awaiting transfer to a different facility. “If we’re not able to provide that, we want to get them to the state hospital as quickly as possible. It’s not like we file a writ just to have them go sit in jail.”

But in David’s case, that’s exactly what happened.

Dr. Paul Appelbaum, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia and former president of the American Psychiatric Association, reviewed the commitment paperwork and initial evaluation filed with the chancery court in David’s case. He said sending David to jail was wrong.

“The sexually inappropriate behavior is a function of his current acute psychosis, and so the proper response to it is to treat the psychosis, which doesn’t happen overnight,” he said.

Dr. Marvin Swartz, a professor of psychiatry at Duke University, said it may have been appropriate to transfer David to another facility, but that elsewhere in the United States, such a transfer would not involve waiting in jail.

Dr. Lauren Stossel, a forensic psychiatrist and former chief of mental health for New York City jails, said that mental health providers have a responsibility to transfer patients to a higher level of care if they can’t provide safe and effective treatment.

Mississippi’s practice of routinely jailing people without criminal charges while they await psychiatric treatment demands systemic change, she said. But in the meantime, crisis center staff shouldn’t avoid commitment at all costs.

“Clinicians need to consider all their patients and staff and make a decision about what they can manage in their facility,” she said. “The fact that jail is a possible alternative is appalling and needs to be factored in, but they also have to be careful about getting in over their heads trying to manage patients they have no way of treating safely or effectively.”

When reviewing the information crisis center staff provided to the chancery court to justify their decision to initiate commitment proceedings, however, Stossel didn’t see a clear explanation of what staff believed the patient needed that they weren’t equipped to provide.

“It’s not clear to me based on this information: what symptoms or behaviors is this patient exhibiting that you can’t manage? What interventions have you already tried? How long did you allow him to respond to treatment before determining a higher level of care was necessary? It’s crucial to require a clear justification to protect the patient from an unnecessarily restrictive outcome.”

Adam Moore, spokesman for the Department of Mental Health, which funds the crisis units, did not answer specific questions about what happened to David. He said in an email statement that a crisis unit may initiate commitment proceedings when their clinical staff feels that someone served there meets commitment criteria or is in need of a higher level of care.

‘I didn’t know I was gonna get sent to jail’

While her son was in jail, Sarah wondered what medications he was taking, concerned that any disruption could worsen his symptoms. She and her daughter, Beth, worried about what he might experience as a young Black man locked up – with no criminal charges – in a Mississippi county jail. They prayed for God to keep him safe.

Sarah called the jail every day to find out how David was doing. During one of those calls, on Jan. 22, a staffer at the jail told her David would have a hearing in court the next day.

It had been 14 days since he was jailed, and 15 since the affidavit requesting his commitment was filed. The Department of Mental Health publishes guidelines saying that the entire process should wrap up within 10 days, but it doesn’t track whether that actually happens.

Special master Adam Emerson, the attorney appointed by a chancellor to preside over commitment hearings, said the county normally holds commitment hearings every Thursday, and sometimes on Tuesdays as well to meet the statutory deadline. Most hearings take place within a week of the writ being served, he said.

He would not comment on David’s case because it is his policy not to discuss specific commitment proceedings, but said that the week of Jan. 15, the entire county court system was shut down due to winter weather, postponing all hearings to the following week.

Emerson said he serves as special master as a way to serve the community where he has lived for nearly his entire life. During a decade as a public defender in the county, he realized many of his clients had mental health or addiction issues that led to criminal charges.

“I continue to believe that early intervention in situations where mental health issues are involved will lead to better outcomes to the individuals and society at large,” he wrote in an email to Mississippi Today.

To make it to the hearing, Sarah had to take the day off of work. At the courthouse in Hernando, she sat in the hallway with three other families of people going through the commitment process.

Eventually, she was called into the courtroom and took a seat in the front row. Deputies escorted her son into the room. He was shackled, with his hands chained to his waist and another chain running down to his feet.

Sarah noticed that almost everyone else in the courtroom was white. She suspected that racism had played a role in her son’s treatment. He is 6-foot-7, and though she knows him as “a gentle giant” who acts like one of her grandchildren, she worries other people are scared of him.

“It’s three strikes against you right there,” she said. “You’re African-American– strike one. African-American male– strike two. Then you’re an African-American male with a mental health disease. You just struck out.”

Emerson said he could not speak to David’s treatment outside of his courtroom, but that race had not played a role in his decision.

“I can only tell you that everyone who comes before my court is treated equally and with dignity and respect,” he said. “A person’s race, ethnicity, gender, religion, sexual preference, etc. is never a factor in our decisions.”

Mississippi Today reviewed the recording of the hearing after filing a motion to unseal it, with a letter of support from Sarah.

At the beginning of the 10-minute hearing, Catherine Davis, the Region IV crisis coordinator who had filed the affidavit against David, explained why she believed commitment was necessary.

Davis said that David had been masturbating at the crisis center, and that he was “hostile,” without saying what that meant exactly.

“When he was redirected he was becoming hostile,” Davis said. “He was pacing, responding to internal stimuli. So they felt at that point he wasn’t safe with the staff and the other clients. So they asked us to do a court commitment.”

When it was his turn to speak, David offered a different account of how he reacted to instructions from staff.

“After they told me the first time, I stopped,” he said, forming his sentences slowly and softly. “I really didn’t know it was a problem. I didn’t know I was gonna get sent to jail. I was just trying to get to the hospital.”

He told the judge he didn’t need more treatment.

Emerson called on Sarah to speak as well. She described the frustration and stress of sending her conservatorship paperwork to the crisis center only to learn days later her son had been taken to jail with no one informing her.

“I have been left out of this the entire time, and I don’t understand why,” she said.

On the recommendation of Davis and two physicians, Emerson ordered David into treatment at a state hospital.

“I’m doing that for your own good, to try to get you stabilized and get you back out,” he said to David.

To Sarah, he added: “Certainly based on where he’s sent, if I were you I’d try to get those records down to them so maybe they can keep you in the loop, OK?”

Before she could talk to or hug her son, Sarah was ushered out of the courtroom. David went back to jail for six more days.

‘How does being incarcerated support one’s mental health?’

On Jan. 29, 20 days after he was first jailed, David was transported to North Mississippi State Hospital.

Moore, the Department of Mental Health spokesman, said that the wait time information the agency had shared with lawmakers was an average and that it does not include any time a person is jailed before their hearing.

“Any individual’s wait time may be more or less than the average wait time for all admissions from a given period of time,” he wrote.

By early April, David was still at the state hospital in Tupelo. When Sarah visited him, she was disturbed that he had little energy, which she attributes to his long list of medications prescribed by the hospital staff. He told her he’s ready to come home, and he talked about trying to get a job.

His mother filed a complaint with the Mississippi Department of Health and with the Attorney General’s Public Integrity Division, which is responsible for prosecuting cases involving the exploitation of vulnerable adults.

She also emailed Wendy Bailey, head of the Department of Mental Health.

“As I deal with DeSoto County, which happens to be one of the fastest growing counties in the state, I am appalled at their antiquated systems of mental health support,” she wrote.

“How does being incarcerated support one’s mental health? What immediate changes can be made to improve upon this system?”

Bailey connected Sarah with Falisha Stewart, director of the Office of Consumer Supports. Stewart said there had been a communication “breakdown” when the Corinth crisis stabilization unit failed to contact Sarah about her son’s transfer to jail. She said the agency had enacted a plan to prevent communication lapses from happening in the future.

“It is unfortunate individuals who deal with mental health issues have to wait in jails for an available bed while being committed,” Stewart wrote. “These laws can only change through the process of speaking with your state representatives.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1903, W.E.B. Du Bois urged active resistance to racist policies

April 27, 1903

W.E.B. Du Bois, in his book, “The Souls of Black Folk,” called for active resistance to racist policies: “We have no right to sit silently by while the inevitable seeds are sown for a harvest of disaster to our children, black and white.”

He described the tension between being Black and being an American: “One ever feels his twoness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

He criticized Washington’s “Atlanta Compromise” speech. Six years later, Du Bois helped found the NAACP and became the editor of its monthly magazine, The Crisis. He waged protests against the racist silent film “The Birth of a Nation” and against lynchings of Black Americans, detailing the 2,732 lynchings between 1884 and 1914.

In 1921, he decried Harvard University’s decisions to ban Black students from the dormitories as an attempt to renew “the Anglo-Saxon cult, the worship of the Nordic totem, the disenfranchisement of Negro, Jew, Irishman, Italian, Hungarian, Asiatic and South Sea Islander — the world rule of Nordic white through brute force.”

In 1929, he debated Lothrop Stoddard, a proponent of scientific racism, who also happened to belong to the Ku Klux Klan. The Chicago Defender’s front page headline read, “5,000 Cheer W.E.B. DuBois, Laugh at Lothrup Stoddard.”

In 1949, the FBI began to investigate Du Bois as a “suspected Communist,” and he was indicted on trumped-up charges that he had acted as an agent of a foreign state and had failed to register. The government dropped the case after Albert Einstein volunteered to testify as a character witness.

Despite the lack of conviction, the government confiscated his passport for eight years. In 1960, he recovered his passport and traveled to the newly created Republic of Ghana. Three years later, the U.S. government refused to renew his passport, so Du Bois became a citizen of Ghana. He died on Aug. 27, 1963, the eve of the March on Washington.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Jim Hood’s opinion provides a roadmap if lawmakers do the unthinkable and can’t pass a budget

On June 30, 2009, Sam Cameron, the then-executive director of the Mississippi Hospital Association, held a news conference in the Capitol rotunda to publicly take his whipping and accept his defeat.

Cameron urged House Democrats, who had sided with the Hospital Association, to accept the demands of Republican Gov. Haley Barbour to place an additional $90 million tax on the state’s hospitals to help fund Medicaid and prevent the very real possibility of the program and indeed much of state government being shut down when the new budget year began in a few hours. The impasse over Medicaid and the hospital tax had stopped all budget negotiations.

Barbour watched from a floor above as Cameron publicly admitted defeat. Cameron’s decision to swallow his pride was based on a simple equation. He told news reporters, scores of lobbyists and health care advocates who had set up camp in the Capitol as midnight on July 1 approached that, while he believed the tax would hurt Mississippi hospitals, not having a Medicaid budget would be much more harmful.

Just as in 2009, the Legislature ended the 2025 regular session earlier this month without a budget agreement and will have to come back in special session to adopt a budget before the new fiscal year begins on July 1. It is unlikely that the current budget rift between the House and Senate will be as dramatic as the 2009 standoff when it appeared only hours before the July 1 deadline that there would be no budget. But who knows what will result from the current standoff? After all, the current standoff in many ways seems to be more about political egos than policy differences on the budget.

The fight centers around multiple factors, including:

- Whether legislation will be passed to allow sports betting outside of casinos.

- Whether the Senate will agree to a massive projects bill to fund local projects throughout the state.

- Whether leaders will overcome hard feelings between the two chambers caused by the House’s hasty final passage of a Senate tax cut bill filled with typos that altered the intent of the bill without giving the Senate an opportunity to fix the mistakes.

- Whether members would work on a weekend at the end of the session. The Senate wanted to, the House did not.

It is difficult to think any of those issues will rise to the ultimate level of preventing the final passage of a budget when push comes to shove.

But who knows? What we do know is that the impasse in 2009 created a guideline of what could happen if a budget is not passed.

It is likely that parts, though not all, of state government will shut down if the Legislature does the unthinkable and does not pass a budget for the new fiscal year beginning July 1.

An official opinion of the office of Attorney General Jim Hood issued in 2009 said if there is no budget passed by the Legislature, those services mandated in the Mississippi Constitution, such as a public education system, will continue.

According to the Hood opinion, other entities, such as the state’s debt, and court and federal mandates, also would be funded. But it is likely that there will not be funds for Medicaid and many other programs, such as transportation and aspects of public safety that are not specifically listed in the Mississippi Constitution.

The Hood opinion reasoned that the Mississippi Constitution is the ultimate law of the state and must be adhered to even in the absence of legislative action. Other states have reached similar conclusions when their legislatures have failed to act, the AG’s opinion said.

As is often pointed out, the opinion of the attorney general does not carry the weight of law. It serves only as a guideline, though Gov. Tate Reeves has relied on the 2009 opinion even though it was written by the staff of Hood, who was Reeves’ opponent in the contentious 2019 gubernatorial campaign.

But if the unthinkable ever occurs and the Legislature goes too far into a new fiscal year without adopting a budget, it most likely will be the courts — moreso than an AG’s opinion — that ultimately determine if and how state government operates.

In 2009 Sam Cameron did not want to see what would happen if a budget was not adopted. It also is likely that current political leaders do not want to see the results of not having a budget passed before July 1 of this year.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mississippi Today

1964: Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was formed

April 26, 1964

Civil rights activists started the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to challenge the state’s all-white regular delegation to the Democratic National Convention.

The regulars had already adopted this resolution: “We oppose, condemn and deplore the Civil Rights Act of 1964 … We believe in separation of the races in all phases of our society. It is our belief that the separation of the races is necessary for the peace and tranquility of all the people of Mississippi, and the continuing good relationship which has existed over the years.”

In reality, Black Mississippians had been victims of intimidation, harassment and violence for daring to try and vote as well as laws passed to disenfranchise them. As a result, by 1964, only 6% of Black Mississippians were permitted to vote. A year earlier, activists had run a mock election in which thousands of Black Mississippians showed they would vote if given an opportunity.

In August 1964, the Freedom Party decided to challenge the all-white delegation, saying they had been illegally elected in a segregated process and had no intention of supporting President Lyndon B. Johnson in the November election.

The prediction proved true, with white Mississippi Democrats overwhelmingly supporting Republican candidate Barry Goldwater, who opposed the Civil Rights Act. While the activists fell short of replacing the regulars, their courageous stand led to changes in both parties.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed1 day ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed1 day agoMissouri lawmakers on the cusp of legalizing housing discrimination

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoPrayer Vigil Held for Ronald Dumas Jr., Family Continues to Pray for His Return | April 21, 2025 | N

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days ago‘Trainwreck on the horizon’: The costly pains of Mississippi’s small water and sewer systems

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days agoTrump touts manufacturing while undercutting state efforts to help factories

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days agoMeteorologist Chita Craft is tracking a Severe Thunderstorm Warning that's in effect now

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days agoFederal report due on Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina’s path to recognition as a tribal nation

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed6 days agoTaking video of military bases using drones could be outlawed | Virginia

-

Mississippi Today3 days ago

Mississippi Today3 days agoStruggling water, sewer systems impose ‘astronomic’ rate hikes