Morsa Images via Getty Images

Laurie Archbald-Pannone, University of Virginia

Knowing which vaccines older adults should get and hearing a clear recommendation from their health care provider about why a particular vaccine is important strongly motivated them to get vaccinated. That’s a key finding in a recent study I co-authored in the journal Open Forum Infectious Diseases.

Adults over 65 have a higher risk of severe infections, but they receive routine vaccinations at lower rates than do other groups. My colleagues and I collaborated with six primary care clinics across the U.S. to test two approaches for increasing vaccination rates for older adults.

In all, 249 patients who were visiting their primary care providers participated in the study. Of these, 116 patients received a two-page vaccine discussion guide to read in the waiting room before their visit. Another 133 patients received invitations to attend a one-hour education session after their visit.

The guide, which we created for the study, was designed to help people start a conversation about vaccines with their providers. It included checkboxes for marking what made it hard for them to get vaccinated and which vaccines they want to know more about, as well as space to write down any questions they have. The guide also featured a chart listing recommended vaccines for older adults, with boxes where people could check off ones they had already received.

In the sessions, providers shared in-depth information about vaccines and vaccine-preventable diseases and facilitated a discussion to address vaccine hesitancy.

In a follow-up survey two months later, patients reported that the most significant barriers they faced were knowing when they should receive a particular vaccine, having concerns about side effects and securing transportation to a vaccination appointment.

The percentage of patients who said they wanted to get a vaccine increased from 68% to 79% after using the vaccine guide. Following each intervention, 80% of patients reported they discussed vaccines more in that visit than they had in prior visits.

Of the 14 health care providers who completed the follow-up survey, 57% reported increased vaccination rates following each approach. Half of the providers felt that the use of the vaccine guide was an effective strategy in guiding conversations with their patients.

Why it matters

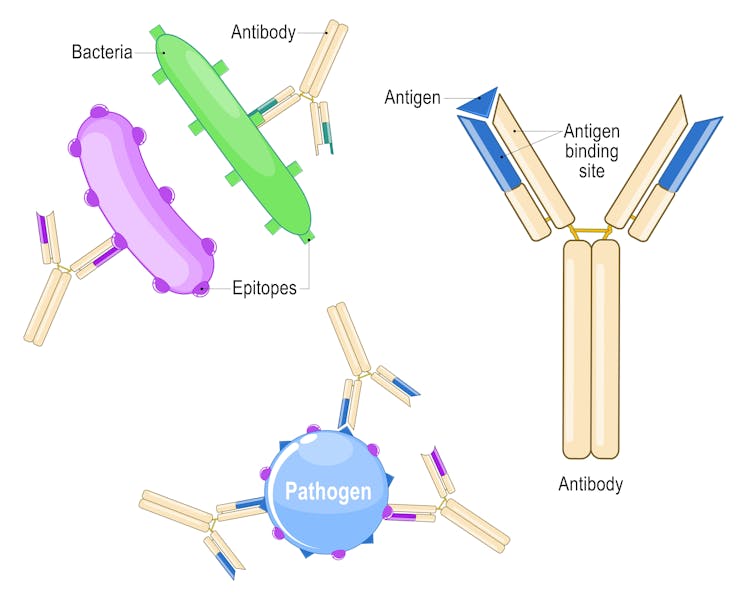

Only about 15% of adults ages 60-64 and 26% of adults 65 and older are up to date on all the vaccines recommended for their age, according to CDC data from 2022. These include vaccines for COVID 19, influenza, tetanus, pneumococcal disease and shingles.

Yet studies consistently show that getting vaccinated reduces the risk of complications from these conditions in this age group.

My research shows that strategies that equip older adults with personalized information about vaccines empower them to start the conversation about vaccines with their clinicians and enable them to be active participants in their health care.

What’s next

In the future, we will explore whether engaging patients on this topic earlier is even more helpful than doing so in the waiting room before their visit.

This might involve having clinical team members or care coordinators connect with patients ahead of their visit, either by phone or through telemedicine that is designed specifically for older adults.

My research team plans to conduct a pilot study that tests this approach. We hope to learn whether reaching out to these patients before their clinic visits and helping them think through their vaccination status, which vaccines their provider recommends and what barriers they face in getting vaccinated will improve vaccination rates for this population.

The Research Brief is a short take on interesting academic work.![]()

Laurie Archbald-Pannone, Associate Professor of Medicine and Geriatrics, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.