Mississippi Today

Shortage of OB-GYNs is leaving Mississippi moms-to-be stranded for care

Kayla Dominick of Meridian knew something was not right – her periods were irregular and she felt constant pressure in her pelvis. She found a local OB-GYN who accepted Medicaid, and he performed an ultrasound of her uterus.

When it was recommended she undergo follow-up testing, including a uterine biopsy, she called the office to ask the doctor or nurse some questions and share concerns about the procedure. After leaving several messages and never hearing back, she decided to find another doctor.

But that didn’t prove simple: There are only 11 licensed OB-GYNs in Lauderdale County, home to Meridian, and its surrounding five counties, according to data from the Office of Mississippi Physician Workforce. Of those 11, only six reportedly practice obstetrics, or deliver babies.

At the same time, almost 28,000 women of reproductive age are living in that six-county area, according to U.S. Census data.

By comparison, in Rankin County, also home to about 28,000 women of reproductive age, there are 42 licensed OB-GYNs.

Mississippi as a whole is experiencing a shortage of these specialists. A recent WalletHub study ranked Mississippi as the worst state to have a baby. It came in 50th in the “midwives and OB-GYNs per capita” category, which it used data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics to determine. It also incorporated the state’s maternal and infant mortality rates – some of the worst in the nation – into the ranking.

More than half of Mississippi counties are considered maternity care deserts, or have no hospitals providing obstetric care, no OB-GYNs and no certified nurse midwives.

But the small number of OB-GYNs – particularly those still practicing obstetrics – in a metropolitan area like Meridian shows how tenuous the current workforce landscape is.

Dr. Norman Connell, market medical director for the OB Hospitalist Group and a Vicksburg-based OB-GYN, said about five years ago, the Meridian area had around 12 or 13 obstetric providers, most of them with privileges at both hospitals. Now, there are six providers on staff at both Ochsner Rush and Anderson Regional Medical Center.

In 2021, as a result of the drop in providers, both hospitals signed an agreement with Connell’s company to supply OB-GYN hospitalists, or providers from across the state, or even out of state, who work solely in an inpatient hospital setting.

“The population of Meridian didn’t shrink, but the area lost over half of the OB providers in a few short years,” Connell said.

Connell said the doctors at his company allow the local OB-GYNs to stay in their clinics more often and see patients they need to see.

“In addition to that, we’re also the doctor for patients who don’t have physicians on staff there … and for people who haven’t gotten prenatal care and show up with an obstetric problem,” he explained.

The group also has contracts with seven other hospitals all over the state, from Magnolia Regional Health Center in Corinth to Mississippi Baptist Medical Center in Jackson.

For Dominick, finding another doctor who accepts Medicaid and who would perform the procedure was a challenge – a surprising one for the native of New Orleans, where health care services are abundant.

“In the New Orleans area, we have an urgent care (clinic) on almost every corner, open 24/7,” she said of the abundance of health care services.

Dominick, like many other women in Meridian, took to a Facebook group for Meridian moms to ask for OB-GYN recommendations. There are several posts in the group from women looking for OB-GYN recommendations, either because they need a new one or because the one they’ve been seeing is too busy for routine appointments like check-ups.

“Best obgyns to go to im tired of waiting to get an appointment at my doctors office I shouldn’t have to sit there for three hours when there’s 3 people in the waiting room or waiting 6 months to even get in,” one woman wrote.

Dominick eventually landed an appointment with Dr. Jennifer Nelson, who has been an OB-GYN in the area for more than 20 years. Nelson, however, recently quit practicing obstetrics after spending the prior two years on call at the hospital 24 nights a month.

Nelson was absolutely exhausted, scrambling from the hospital to the clinic and back.

She remembers one night when several other OB-GYNs at the hospital were out of town, and she was sick with the flu. She wound up working anyway.

Anywhere from 40% to more than 75% of OB-GYNs experience burnout, studies show – in the middle to upper one-third of medical specialties.

On top of the physical and mental burnout from around-the-clock work, she had many high-risk patients to see in her clinic – patients who required a lot of time, she said, and often with insurance that did not reimburse well. About half of her patients were on Medicaid, she said.

Medicaid payments for physician services are well below Medicare payments, which are below commercial insurance rates. Mississippi also has one of the lowest average commercial reimbursement rates for both inpatient and outpatient services in the nation, according to a Milliman white paper.

“It’s expensive to do OB here. I ran my numbers one month – if every one of my OB patients had been Medicaid … I would not have been able to pay my overhead with my nurses, and that’s with me working for free, totally taking my salary out of it,” she said. “I would have been about $100,000 short.”

In her clinic now, she treats Medicaid patients when they are referred to her clinic and, on a case-by-case basis, unreferred patients. She said because the clinic is not designated a “rural health clinic” by the federal government, Medicaid reimbursements for services are very low.

“The (gynecology) side is very low reimbursement for general services if you don’t have a rural health clinic designation,” she explained.

Further compounding the issue is how sick the patient population in the area – and across the state – is.

“We have the sickest patient population, so they’re litigious, time consuming – I did a lot of high-risk pregnancies. It’s a lot of coming up at two in the morning to check on people who are super sick,” she said.

Mississippi leads the nation in areas such as obesity, high blood pressure and diabetes – all conditions that make pregnancy more dangerous and require more time and services from OB-GYNs and other maternal health practitioners. These conditions often lead to worse outcomes for women and babies.

As OB-GYNs stop practicing or retire, both in Mississippi and nationwide, they aren’t being replaced at the same rate. And it’s unknown how last year’s Dobbs decision that overturned Roe v. Wade is affecting the OB-GYN workforce in Mississippi, though other states with similar restrictive abortion laws have seen providers leave because of enhanced legal risks.

Dr. Michelle Owens, a maternal fetal medicine specialist who worked at the University of Mississippi Medical Center for nearly 20 years, said she suspects because the state’s laws have always been so restrictive in regards to abortion, Dobbs is not having an immediate effect on providers who live here.

“I think if anything, if people are concerned about the restrictive nature of practice of obstetrics and gynecology as it pertains to terminations services, that it (Dobbs) would probably be more influential on preventing people who want to provide that care. Those people aren’t going to come here (to Mississippi),” she said.

In a state with such a severe shortage, one must consider the ramifications of that, she said.

“The more we say we're in favor of allowing or condoning government interference in exam rooms, we have to also recognize there are some unintended consequences to those decisions – they don’t just happen in a vacuum,” she said.

There’s currently only one OB-GYN residency program in the state at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, and the program graduates six residents each year. Of the most recent graduates, only two stayed in Mississippi – prior years’ numbers average about the same.

On top of that, there have been changes in how OB-GYNs work over the last decade nationally. Traditionally OB-GYNs worked at private clinics and had privileges at hospitals. Now, however, many OB-GYNs are hospitalists, or OB-GYNs who work solely in the inpatient setting, according to Dr. Elizabeth Lutz, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology and the residency program director at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

And more OB-GYNs today wind up completing fellowships, or going into a subspecialty such as maternal fetal medicine.

“Nowadays, closer than 30 to 40% of OB-GYN residents go into fellowship – that’s grown dramatically,” said Lutz, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology and the residency program director at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Both Ochsner Rush, where Nelson previously had privileges, and Anderson in Meridian began contracting with the OB Hospitalist Group in 2021 to fill in the gaps created by the shortage. About eight OB-GYNs from across the state – and even some from out of state – work shifts at both hospitals.

Anderson averages about 1,020 births per year, according to a hospital spokesperson. Ochsner Rush averages just under 1,000 births annually.

“Due to a shortage of OB-GYN’s in east central Mississippi, Anderson Regional Health System partners with a OB Hospitalist group to supplement our three practicing OB-GYN’s in providing 24-hour obstetrics coverage every day,” said Dr. Keith Everett, chief medical officer at Anderson Regional Health System.

Both hospitals also employ advanced practice nurses called certified nurse midwives – Ochsner Rush has four on staff – who manage the care of low-risk patients. The midwives are also skilled at counseling and education of patients in areas such as nutrition, childbirth preparation and breastfeeding.

The use of certified nurse midwives in Mississippi is rare: there are fewer than 30 in the state, and only a few hospitals, including the two in Meridian, allow them to deliver babies.

Connell said he thinks the company’s role in the area – and in the state – will only continue to grow.

“I think Meridian paints a picture of (why this work is important),” he said. “... It’s a work in progress. We’re at the very beginning of making things better.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

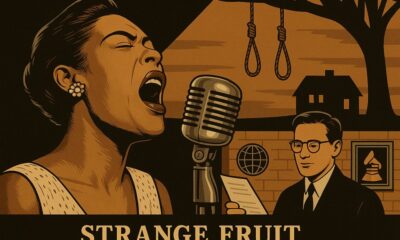

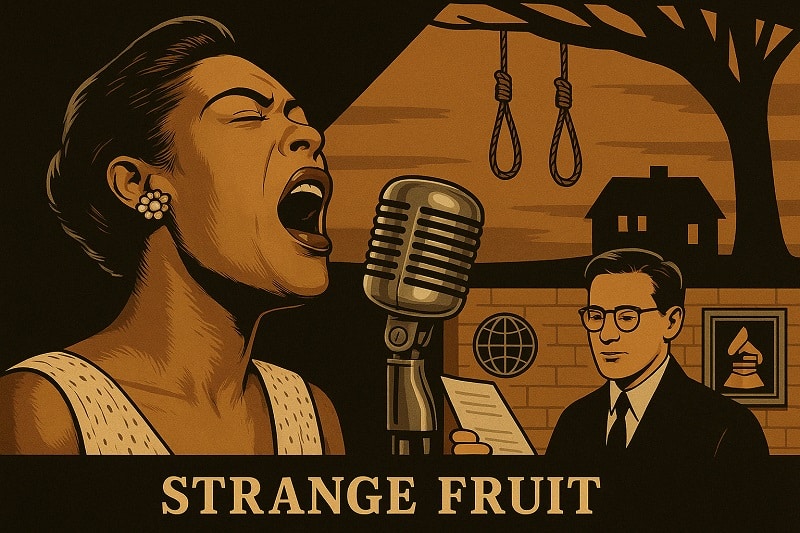

On this day in 1939, Billie Holiday recorded ‘Strange Fruit’

April 20, 1939

Legendary jazz singer Billie Holiday stepped into a Fifth Avenue studio and recorded “Strange Fruit,” a song written by Jewish civil rights activist Abel Meeropol, a high school English teacher upset about the lynchings of Black Americans — more than 6,400 between 1865 and 1950.

Meeropol and his wife had adopted the sons of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were orphaned after their parents’ executions for espionage.

Holiday was drawn to the song, which reminded her of her father, who died when a hospital refused to treat him because he was Black. Weeks earlier, she had sung it for the first time at the Café Society in New York City. When she finished, she didn’t hear a sound.

“Then a lone person began to clap nervously,” she wrote in her memoir. “Then suddenly everybody was clapping.”

The song sold more than a million copies, and jazz writer Leonard Feather called it “the first significant protest in words and music, the first unmuted cry against racism.”

After her 1959 death, both she and the song went into the Grammy Hall of Fame, Time magazine called “Strange Fruit” the song of the century, and the British music publication Q included it among “10 songs that actually changed the world.”

David Margolick traces the tune’s journey through history in his book, “Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday and the Biography of a Song.” Andra Day won a Golden Globe for her portrayal of Holiday in the film, “The United States vs. Billie Holiday.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Mississippians are asked to vote more often than people in most other states

Not long after many Mississippi families celebrate Easter, they will be returning to the polls to vote in municipal party runoff elections.

The party runoff is April 22.

A year does not pass when there is not a significant election in the state. Mississippians have the opportunity to go to the polls more than voters in most — if not all — states.

In Mississippi, do not worry if your candidate loses because odds are it will not be long before you get to pick another candidate and vote in another election.

Mississippians go to the polls so much because it is one of only five states nationwide where the elections for governor and other statewide and local offices are held in odd years. In Mississippi, Kentucky and Louisiana, the election for governor and other statewide posts are held the year after the federal midterm elections. For those who might be confused by all the election lingo, the federal midterms are the elections held two years after the presidential election. All 435 members of the U.S. House and one-third of the membership of the U.S. Senate are up for election during every midterm. In Mississippi, there also are important judicial elections that coincide with the federal midterms.

Then the following year after the midterms, Mississippians are asked to go back to the polls to elect a governor, the seven other statewide offices and various other local and district posts.

Two states — Virginia and New Jersey — are electing governors and other state and local officials this year, the year after the presidential election.

The elections in New Jersey and Virginia are normally viewed as a bellwether of how the incumbent president is doing since they are the first statewide elections after the presidential election that was held the previous year. The elections in Virginia and New Jersey, for example, were viewed as a bad omen in 2021 for then-President Joe Biden and the Democrats since the Republican in the swing state of Virginia won the Governor’s Mansion and the Democrats won a closer-than-expected election for governor in the blue state of New Jersey.

With the exception of Mississippi, Louisiana, Kentucky, Virginia and New Jersey, all other states elect most of their state officials such as governor, legislators and local officials during even years — either to coincide with the federal midterms or the presidential elections.

And in Mississippi, to ensure that the democratic process is never too far out of sight and mind, most of the state’s roughly 300 municipalities hold elections in the other odd year of the four-year election cycle — this year.

The municipal election impacts many though not all Mississippians. Country dwellers will have no reason to go to the polls this year except for a few special elections. But in most Mississippi municipalities, the offices for mayor and city council/board of aldermen are up for election this year.

Jackson, the state’s largest and capital city, has perhaps the most high profile runoff election in which state Sen. John Horhn is challenging incumbent Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba in the Democratic primary.

Mississippi has been electing its governors in odd years for a long time. The 1890 Mississippi Constitution set the election for governor for 1895 and “every four years thereafter.”

There is an argument that the constant elections in Mississippi wears out voters, creating apathy resulting in lower voter turnout compared to some other states.

Turnout in presidential elections is normally lower in Mississippi than the nation as a whole. In 2024, despite the strong support for Republican Donald Trump in the state, 57.5% of registered voters went to the polls in Mississippi compared to the national average of 64%, according to the United States Elections Project.

In addition, Mississippi Today political reporter Taylor Vance theorizes that the odd year elections for state and local officials prolonged the political control for Mississippi Democrats. By 1948, Mississippians had started to vote for a candidate other than the Democrat for president. Mississippians began to vote for other candidates — first third party candidates and then Republicans — because of the national Democratic Party’s support of civil rights.

But because state elections were in odd years, it was easier for Mississippi Democrats to distance themselves from the national Democrats who were not on the ballot and win in state and local races.

In the modern Mississippi political environment, though, Republicans win most years — odd or even, state or federal elections. But Democrats will fare better this year in municipal elections than they do in most other contests in Mississippi, where the elections come fast and often.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mississippi Today

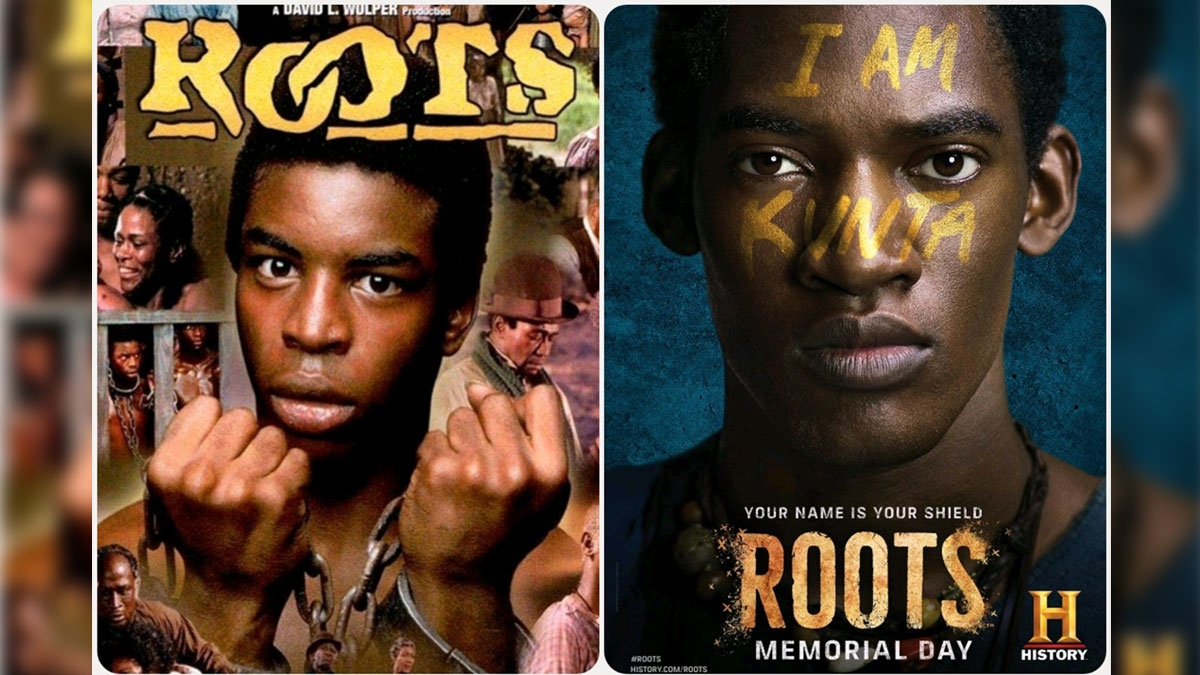

On this day in 1977, Alex Haley awarded Pulitzer for ‘Roots’

April 19, 1977

Alex Haley was awarded a special Pulitzer Prize for “Roots,” which was also adapted for television.

Network executives worried that the depiction of the brutality of the slave experience might scare away viewers. Instead, 130 million Americans watched the epic miniseries, which meant that 85% of U.S. households watched the program.

The miniseries received 36 Emmy nominations and won nine. In 2016, the History Channel, Lifetime and A&E remade the miniseries, which won critical acclaim and received eight Emmy nominations.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoFoley man wins Race to the Finish as Kyle Larson gets first win of 2025 Xfinity Series at Bristol

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoFederal appeals court upholds ruling against Alabama panhandling laws

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days agoTwo dead, 9 injured after shooting at Conway park | What we know

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed3 days agoDrivers brace for upcoming I-70 construction, slowdowns

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days agoFDA warns about fake Ozempic, how to spot it

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed4 days agoLieutenant governor race heats up with early fundraising surge | Virginia

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed4 days agoThursday April 17, 2025 TIMELINE: Severe storms Friday

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days agoAbandoned property causing issues in Pine Lawn, neighbor demands action