Mississippi Today

Sex Abuse, Beatings and an Untouchable Mississippi Sheriff

Sex Abuse, Beatings and an Untouchable Mississippi Sheriff

Terry Grassaree was dogged for years by questions about how he did his job as a law enforcement officer in Macon, Miss., a tiny, rural town near the state’s eastern border.

There were allegations of rape inside the jail that Mr. Grassaree supervised, and lawsuits claiming that he covered up the episodes. At least five people, including one of his fellow deputies, accused him of beating others or choking them with a police baton.

Mr. Grassaree survived it all, rising in the ranks of the Noxubee County Sheriff’s Department, from a deputy mopping floors, to chief deputy, to the elected position of sheriff, making him one of the most powerful figures in town.

Now, more than three years after losing an election and retiring, and 16 years after a woman first claimed that Mr. Grassaree pressured her to lie about being raped, the former sheriff faces criminal charges.

A federal indictment filed in October accuses him of committing bribery in 2019, near the end of his eight-year tenure as sheriff, and of lying to federal agents when they questioned him about whether he requested sexually explicit photographs and videos from a female inmate. Mr. Grassaree has denied the charges and pleaded not guilty.

But an investigation by the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reportingat Mississippi Todayand The New York Times reveals that allegations of wrongdoing against Mr. Grassaree have been far more wide-ranging and serious than those federal charges suggest. The investigation included a review of nearly two decades of lawsuit depositions and a previously undisclosed report by the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation.

At a minimum, the documents detail gross mismanagement at the Noxubee County jail that repeatedly put female inmates in harm’s way. At worst, they tell the story of a sheriff who operated with impunity, even as he was accused of abusing the people in his custody, turning a blind eye to women who were raped and trying to cover it up when caught.

Over nearly two decades, as allegations mounted and Noxubee County’s insurance company paid to settle lawsuits against Mr. Grassaree, state prosecutors brought no charges against him or others accused of abuses in the jail. A federal investigation dragged on for years, and led to charges last fall, a few weeks after reporters started asking authorities about the case.

Even now, no higher authority has reviewed how Mr. Grassaree ran the jail or whether his policies endangered women, because in Mississippi, as in many states, rural sheriffs are left largely to police themselves and their jails.

In 2006, after Mr. Grassaree and his staff left jail cell keys hanging openly on a wall, male inmates opened the doors to the cell of two women inmates and raped them, according to statements the women gave to state investigators. One of the women said Mr. Grassaree pressured her to sign a false statement to cover up the crimes, according to the state police report that has never been made public.

About a year later, in a lawsuit, four people who had been arrested gave sworn statements accusing Mr. Grassaree of violence. Two of the people said he choked or beat them while they were in his custody. A third said he pinned her against a wall and threatened to let a male inmate rape her.

In 2019, a jailed woman told investigators that she had been coerced into having sex with two deputies who offered her a cellphone in exchange for her compliance. Instead of punishing the deputies, she claimed in a lawsuit against the county, Mr. Grassaree demanded that she send him explicit pictures and videos of herself. The federal indictment also accuses Mr. Grassaree of using his cellphone to facilitate a bribe, which experts say could have been the perks the woman says she received.

All told, at least eight men — including four deputies and Mr. Grassaree himself — have been accused of sex abuse by women inmates who were being held in the Noxubee County jail while Mr. Grassaree was in charge.

Over the years, the accusations of rape and other misconduct at the jail have been investigated separately by the FBI, the Department of Justice and the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation. No rape or assault charges have been filed.

Mr. Grassaree has denied all of the allegations against him and has faced no disciplinary action. His lawyer declined to comment further.

Holding people accountable for rapes and assaults behind bars is difficult under the best of circumstances. There is little to protect incarcerated victims and witnesses from retaliation for speaking up. When they do come forward, they are often dismissed as not credible, especially if the person accused is a law enforcement officer.

What happened inside the Noxubee jail, and how the authorities responded, is a case study in how those difficulties can be even harder to surmount in rural places, where jails are the exclusive domain of a county sheriff who operates largely without oversight.

No state agency oversees Mississippi’s county jails, and no state regulator has the authority to fine a sheriff for endangering people in custody or for failing to train the staff who operate the jail. In 2017, state lawmakers stopped providing funds for jail inspections by the Mississippi Department of Health, removing even the basic requirement that the facilities meet food safety and cleanliness requirements.

“They are closed-off institutions, and the people held inside them are unpopular and politically powerless,” said David Fathi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union National Prison Project. “That makes them ripe for neglect and abuse that is entirely foreseeable.”

Scott Colom, the elected district attorney for Noxubee County, took office in 2016 and was not involved in the investigation of the 2006 rape allegations.

After learning of the more recent allegations against Mr. Grassaree and his deputies, Mr. Colom said, he notified federal authorities and worked with them on an investigation. Although he believed the evidence against Mr. Grassaree in the case was “clear and strong,” Mr. Colom said he knew it would be tough to seat an impartial jury in Noxubee County. He has twice been forced to cancel criminal trials because there were too few potential jurors available, he said, and neither of those cases involved a public official.

Darren J. LaMarca, U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Mississippi, declined to comment on the case and so did others responsible for investigating the alleged abuses in the Noxubee County jail.

Mr. Grassaree spoke briefly in an interview about his professional history, but would not answer detailed questions about the 2006 rape cases or the more recent allegations related to his federal charges.

Mary Taylor, a retired dispatcher who worked full time at the jail from 1988 to 2017, said in a phone interview that in her years at the jail she never witnessed any sexual abuse.

She said she wasn’t working on the day the two women said the rapes took place in 2006, but that she doesn’t believe their version of events.

“My belief? They weren’t raped,” Ms. Taylor said. “They did that to get out of jail.”

She maintained that it’s “impossible for one man to rape a woman, unless she’s not moving, unless it’s a Bill Cosby thing.”

“They could have yelled out and told somebody,” she said. “You can’t rape the unwilling.”

Building a tough reputation

When Terry Grassaree was born in Macon in 1962, the idea that he could one day be sheriff seemed far-fetched.

In Macon, which briefly served as Mississippi’s capital during the Civil War, only white men worked as law enforcement officers in those days. The county had a long history of violence against African Americans, including the massacre of 13 Black Mississippians at a church, gunned down by nightriders on a single August night in 1871. The sheriff at the time arrested no one.

Though the county’s population is mostly Black, every sheriff elected in Noxubee County was white until 1988, when Albert Walker became the first Black man to hold the office. Mr. Grassaree, his handpicked successor, was the second.

Mr. Grassaree started his law enforcement career as a police officer in Macon and in nearby Brooksville, and sold insurance on the side to help make ends meet. Sheriff Walker hired him as a county deputy in 1992 and put him to work mopping floors, among other duties, at the county jail. Mr. Grassaree was also a deputy coroner, paid $85 for each body he handled.

He worked his way up to chief deputy, and took on running the jail.

Mr. Grassaree, known to keep order by issuing physical threats, said in an interview last year that he drew inspiration from the professional wrestler “Stone Cold” Steve Austin.

“Even while they were whipping him, he was still the toughest guy on the mat,” Mr. Grassaree said. “He’s like, ‘Is that all you’ve got?’ No matter how long a man whips you, he will get tired. He might think he’s winning. The only thing you’ve got to do is hold out.”

This idea, he said, became the foundation for how he behaved when he put on his uniform.

Early in his career, he beefed his 6-foot-2 frame up to 230 pounds, and people started calling him “Big Dog.” Not many people crossed him after that, he said.

His reputation for being aggressive spread across town. In a 2006 letter to the editor in the local paper, a mother complained that Mr. Grassaree had threatened her 16-year-old son. The boy, she wrote, had fought with Mr. Grassaree’s son at school.

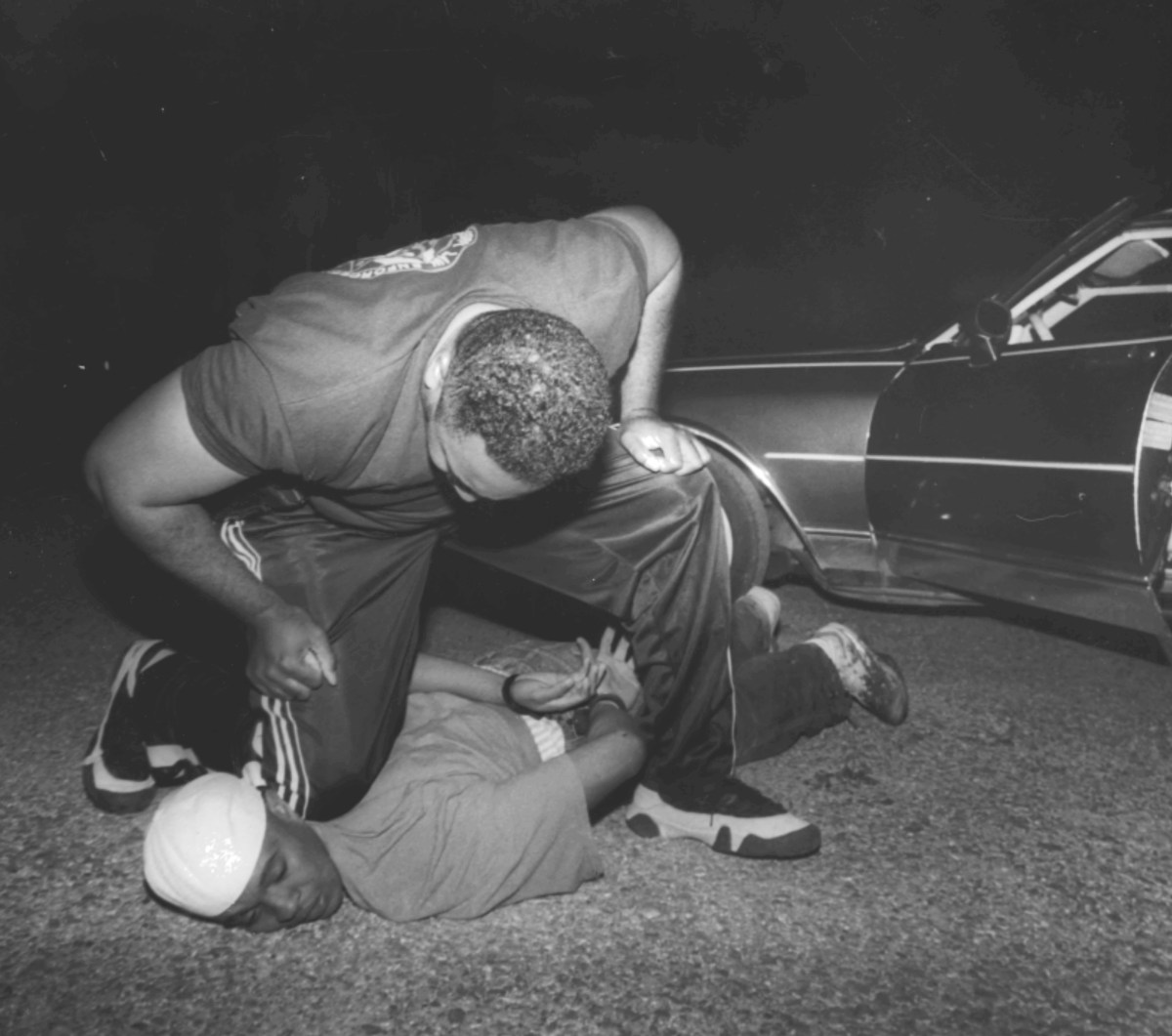

The editor of the same newspaper, The Macon Beacon, arrived to cover an arrest near a nightclub in 2000 and snapped a picture of Mr. Grassaree kneeling on a man’s neck. The photo made the front page.

People who passed through the jail describe being attacked by Mr. Grassaree when he thought they were causing trouble. Four people gave sworn statements about such attacks as part of a 2005 lawsuit against Mr. Grassaree and Noxubee County filed by former deputy Kendrick Slaughter. In the lawsuit, Mr. Slaughter claimed that Mr. Grassaree tried to bribe him not to run for City Council, and then hauled him to jail for talking to the FBI about the alleged bribe.

Noxubee County’s insurance company settled the suit for an undisclosed amount.

The four sworn statements accuse Mr. Grassaree of a number of violent acts, which he has denied committing. One man wrote that while he was handcuffed in a courtroom in 2002, Mr. Grassaree beat him until a judge came off the bench to rescue him.

Another man said in his sworn statement that Mr. Grassaree choked him with his nightstick and warned him to follow his orders. The man said Mr. Grassaree told him, “I’ll shoot you in the head! I’m the Big Dog! I’m Number One! This my jail!”

A 19-year-old woman said Mr. Grassaree hit her twice with his nightstick and threw her against a wall after accusing her of stealing potato chips from a man held in jail. Mr. Grassaree “spread my legs apart with his foot,” she said in her deposition.

Then, she said, he told her that he ought to let the inmate rape her.

A jail with no rules

The jail that Mr. Grassaree oversaw for most of his career sits frozen in time on Industrial Road on the outskirts of Macon, next to the old Purina pet food mill that now produces feed for catfish farms.

The building has been locked and empty since about 2014, when Mr. Grassaree and his deputies packed up and moved to a new facility down the street. Inside the old jail, a blackened mix of dirt, rust and mold has crept over the white iron cell doors. Bags of trash and dusty bed linens litter the remaining furniture and the floor.

When Mr. Grassaree was put in charge of this building in the 1990s, he inherited a jailhouse that essentially operated without rules. Jail workers allowed inmates to come and go from the building without logging the inmates’ movements or supervising them closely.

The onlypolicies about the jail that appear in the 2003 Noxubee County Sheriff’s Policy Manual center on the use of force. None tell how to run the jail.

For years, certain inmates were let out of their cells to help cook, pass out food trays and clean.

Kennedy Brewer, who entered the jail in 2002, was one of the facility’s most trusted inmates. Eyebrows were raised when he showed up at a court hearing on his own, having driven himself to the courthouse without a deputy to escort him, according to Forrest Allgood, the district attorney at the time.

Mr. Brewer spent five years at the jail waiting to be retried after DNA evidence proved he had been wrongly convicted of sexually abusing and murdering a 3-year-old girl. When prosecutors gave up on a new trial, Mr. Brewer was released, and his case was featured in the Netflix documentary series “The Innocence Files.”

Testifying under oath as a witness in a lawsuit in 2007, Mr. Brewer said he served as a jail trusty, or an inmate with special privileges, and had access to keys that opened each cell. He said he would check newly arrested people into the jail and that he once escorted an inmate to a cell with no one else present.

Mr. Grassaree has denied that inmates were allowed to use jail keys without supervision.

On a June day in 2006, Mr. Brewer had no problem getting into the women’s cell block undetected.

He grabbed the jailer’s keys off the nail hanging on the wall and slipped down the short hallway that ran the length of jail. In a building smaller than a McDonald’s, he and a fellow inmate didn’t have to go far. There were no guards patrolling the halls and no surveillance cameras to catch any movements.

When Mr. Brewer unlocked the cell door, one of the women inside was laying down for a nap.

Then Brewer was on top of her, grabbing her arms and forcing her down, according to statements the first woman later gave to state agents.

“No, I don’t want to do this,” she begged, according to her statements.

Then she looked for her cellmate, Jessie Levette Douglas. She told investigators she saw another inmate, Laterris Goodwin, on top of her.

It was all over in moments.

The woman who originally reported the rapes declined to be interviewed for this article. Ms. Douglas died of renal failure in a state prison in 2018.

When investigators interview rape victims, they are supposed to remain impartial. But when Mr. Grassaree, who was chief deputy at the time, found the woman crying on the floor, he stood over her and shouted, the woman said in a deposition taken as part of her subsequent lawsuit against the county. He and another member of the sheriff’s office yelled that she couldn’t tell anybody about the rape and that she was “going to make them lose their jobs and make the department look bad,” according to her sworn statement.

“They kept berating me as if I had done something wrong,” she said.

When state agents arrived the next day at the request of the sheriff’s office, Mr. Grassaree handed them everything they needed to dismiss the allegations, including signed statements from two of the men saying the women had invited them to have sex, and more important, a statement from Ms. Douglas saying everything she saw and experienced was consensual.

If Mr. Grassaree and his deputies had been in charge of the investigation, it might have ended there. But when state agents interviewed Ms. Douglas, her story changed.

She told investigators that she and her cellmate had been raped that day and that she lied in her first statement because Mr. Grassaree had pressured her to cover up what happened.

Mr. Grassaree “told me to tell everybody the sex was consensual and that for me to ‘help a brother,’ referring to Brewer,”Ms. Douglaswrote in a later statement. “He told me to tell everybody that we put on a freak show for the male inmates.”

In reality, Ms. Douglas told the agents, three men incarcerated at the jail — Mr. Brewer, Mr. Goodwin and Michael Slaughter — had entered her locked cell at different times on the same day and had raped her.

In statements to investigators, Mr. Slaughter, Mr. Brewer and Mr. Goodwin denied that they had raped the women, claiming that the sex was consensual.

In an interview from 2022, Mr. Brewerdenied ever having sex with anyone inside the jail. Neither Mr. Slaughter nor Mr. Goodwin could be reached for comment.

Both women were given polygraph tests, and the examiner concluded that they were telling the truth, according to state investigators’ records. Mr. Goodwin and Mr. Slaughter failed polygraph tests; Mr. Brewer declined to take one.

State agents shared their findings with federal and state prosecutors, and the case was presented to a Noxubee County grand jury. The grand jury decided not to issue charges.

Legal experts say Mr. Grassaree could have been investigated for obstructing justice in the case. That never happened, and neither did an investigation of practices in the jail, where agents concluded that four rapes had taken place.

Noxubee County’s insurance company settled the woman’s lawsuit in 2009. The Macon Beacon reported that she was paid $375,000.

Sabrina Campbell said her sister, Ms. Douglas — the woman who said she was raped by three inmates and who died many years later — wanted the public to know what happened to her. “I don’t want my sister to have died in vain,” Ms. Campbell said.

The rapes devastated her sister, who never stopped battling nightmares afterward, she said. “She was scared all the time. She would tell nieces and nephews about the jail, ‘Don’t ever come here, because your life is over.’”

Another round of allegations

Allegations of sexual abuse at the Noxubee County jail did not end with the 2006 case.

In 2020, Elizabeth Layne Reed,a woman incarcerated at the jail, made explosive allegations against the men she encountered there. In a lawsuit she filed that year, she accused two deputies, Vance Phillips and Damon Clark, of coercing her into having sex.

She said the men gave her a cellphone and other perks so that she would have sexual encounters with them in remote spots around the jail or when the deputies checked her out of the facility. The deputies even put a sofa in her jail cell, she said.

Ms. Reed said in an interview that she wanted the public to know what happened to her in the hope that others would come forward. “It made me terrified to trust anybody,” she said. “Women in jail and prison need to be protected.”

According to her lawsuit, Mr. Grassaree knew all about his deputies’ “sexual contacts and shenanigans,” but did nothing to “stop the coerced sexual relationships.” Mr. Grassaree denied any knowledge of what deputies were doing. “Are you a boss?” he said. “Do your employees tell you everything they do?”

Instead of intervening, the lawsuit alleged, the sheriff “sexted” her and demanded that she use the phone the deputies had given her to send him “a continuous stream of explicit videos, photographs and texts” while she was in jail. She also alleged in the lawsuit that Mr. Grassaree touched her in a “sexual manner.”

The lawsuit was settled for an undisclosed amount.

News outlets in Mississippi made brief mention of the lawsuit, but government officials at all levels, including federal and state prosecutors, were silent for two years about what, if anything, they were doing to investigate the allegations it raised, and whether they had found evidence to support them.

A review by the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting and The New York Times of documents filed in the lawsuit, along with documents fromthe preceding2019 state investigation, reveals that Ms. Reedaccused other deputies besides Mr. Phillips and Mr. Clark of sexual harassment and abuse. None of the other deputies has been charged or named publicly. It is unclear whether the FBI investigated those allegations.

The federal bureau’s investigation into Mr. Grassaree, Mr. Phillips and Mr. Clark took more than two years to yield charges, even though investigators had confessions of sexual contact from the deputies as well as text messages between the woman and the three men. In fall of 2022, several weeks after reporters began asking authorities about the case, Mr. LaMarca successfully sought indictments against Mr. Grassaree and Mr. Phillips on bribery charges. Mr. Clark has not been indicted.

Ms. Reed hoped that other deputies, including Mr. Clark, would be held accountable, she said. “They’re still walking around free, not worried about any charges.”

Ms. Reed said that she felt sick to her stomach when she found out that neither Mr. Grassaree nor Mr. Phillips had been directly charged in connection with her allegations of sex abuse. Lawyers for Mr. Phillips did not immediately respond to requests for comment. Mr. Clark could not be reached for comment.

The indictments do not mention sexual abuse. Along with bribery, Mr. Grassaree was also charged with lying to the F.B.I. in denying that he had “requested and received” nude photos and videos from Ms. Reed. A trial is scheduled for summer.

Julie Abbate, who served as the deputy chief of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division from 2003 to 2018 and reviewed the allegations at the news organizations’ request, said the federal prosecutors could have explored criminal charges against Mr. Grassaree and his deputies for violating the civil rights of women in his facility.

The question of whether to bring federal charges in the case may have been complicated by guidance the Department of Justice issued in 2018, saying that law enforcement officers cannot be federally prosecuted for violating a person’s civil rights if the person “truly made a voluntary decision as to what she wanted to do with her body,” particularly if she received a benefit or special treatment in exchange for sex.

But Ms. Reed’s decisions in the episode in the Noxubee County jail were “not free-will choices,” said Andrea Armstrong, a law professor at Loyola University, and the cellphone Ms. Reed received from deputies “was the vehicle by which more abuse could be directed towards her.”

Mississippi law makes it a crime for law enforcement officers to engage in sexual acts with incarcerated people. Prosecutors are not required to prove the victims were physically overpowered or even that they told their abuser to stop.

But the district attorney’s office that handles criminal cases in Noxubee County chose to pass the 2020case on to federal prosecutors, instead of seeking charges under the state law, because of worries about getting a fair jury in the county. When asked about federal prosecutors’ decision to charge Mr. Grassaree and Mr. Phillips with bribery in the case, the district attorney, Mr. Colom, said, “I trust federal authorities to use the best statutes.”

Ms. Abbate said the allegations about abuses in the Noxubee County jail were indicative of a larger, pervasive problem at the facility and a harmful culture inside the sheriff’s office. That culture, she said, undoubtedly endangered inmates and allowed abuses to continue.

“The allegations that come to light are almost always just the tip of the iceberg,” said Ms. Abbate, who is now director of Just Detention International, an organization dedicated to ending sexual abuse in correctional facilities. Referring to the 2006 and 2020 cases, she said, “I guarantee you that these two instances are not the only ones.”

This article was co-reported by The New York Times and the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting at Mississippi Today.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Gov. vetoes bill providing hospitals ‘stability’

Gov. Tate Reeves vetoed a bill Thursday that would help stabilize hospitals, calling it the “Grady Twin” of a bill he vetoed in March.

Lawmakers made some changes to the previously vetoed legislation in a new bill, but kept much the same. Reeves cited many of his same concerns this time around, including alleged contradictions and the loom of a deficit.

The bill, authored by Senate Medicaid Chairman Kevin Blackwell, R-Southaven, sought to make several changes to the Medicaid program – from mandating providers screen mothers for postpartum depression to requiring the agency to cover a new sleep apnea device.

Blackwell did not respond to a request for comment by the time of publication.

Arguably the largest impact of Senate Bill 2386 would have been that it called for locking in place supplemental payment programs that have been a lifeline for hospitals – but which are unreliable as they vary from year to year, according to Richard Roberson, CEO of the Mississippi Hospital Association.

That fluctuation makes it difficult for hospitals to plan what services they can offer.

“The supplemental payment language was intended to offer better budget predictability as hospitals move through these uncertain times and instructed the Division (of Medicaid) to maximize federal funding,” Roberson said. “… Hospitals, like other businesses, need stability to continue to serve their communities effectively.”

Supplemental payment programs bring in around $1.5 billion federal dollars to Mississippi hospitals each year.

Reeves said in his veto statements for both bills that locking the payment program in place is in contradiction with another of the bill’s mandates, which would change the program to allow out-of-state hospitals that border Mississippi to participate in the program.

“It is logically nonsensical for Senate Bill 2386 to, on the one hand, freeze the MHAP, while on the other hand, mandate that the Division open the program to include an additional hospital.”

But Roberson said the language of the bill would not prohibit the programs from growing – it would merely clarify what hospitals need to do to get paid.

Reeves again said the bill “seeks to expand Medicaid.” The bill brings forth code sections related to eligibility requirements, but it doesn’t call for expanding the Medicaid population by increasing the income threshold, which is what is typically referred to as Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act.

Thursday’s vetoed bill was hospitals’ last recourse for stabilizing their budgets via legislation.

Richardson says the Mississippi Hospital Association has now turned its sights toward the Division of Medicaid to secure hospitals’ payment programs without the help of the Legislature.

“With or without Senate Bill 2386, we are hopeful the Division will work to stabilize the model,” Roberson said.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mississippi Today

Parents, providers urge use of unspent TANF for child care

Child care providers, parents, children, legislators and advocates gathered outside the state Capitol Thursday to call on Mississippi to use unspent welfare funds and resume accepting child care certificate applications.

Last month, the Mississippi Department of Human Services announced it will temporarily stop accepting new applications, redetermination applications and “add a child” applications for the child care certificate program for certain families as the result of the loss of COVID-19 relief funds. The hold, started March 31, will continue indefinitely. The program provides child care vouchers to eligible families, often with a co-payment fee.

MDHS explained that without the COVID-19 relief funding the number of families with child care certificates is more than it can support long term. When asked how long the hold would last, chief communications director Mark Jones explained the hold would end when the number of children with certificates dropped below 27,000 children and $12 million in monthly costs.

The week before the hold began, on March 28, 36,186 children had child care certificates. 25,300 of them fit into one of the MDHS’s priority categories. 10,800 did not.

The Mississippi Low-Income Child Care Initiative, Child Care Directors Network Alliance, Mississippi Delta Licensed Child Care Providers, and Mississippi Black Women’s Roundtable organized Thursday’s gathering and press conference to implore MDHS to tap into unused TANF funds to book the child care payment program.

“DHS has about $156 million in money from prior grant years that has gone unspent,” said Carol Burnett, MLICCI’s executive director, at the press conference.

The child care payment program gets funding from federal and state sources. It received $127 million from the Child Care Development Fund in fiscal year 2024, as well as $7 million in state appropriations, and $25.9 million transferred from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families grant.

That $25.9 million is 30% of the state’s annual TANF grant money transferred into funds for child care certificates. It is the maximum amount they’re allowed to transfer under federal law. The state also spends 85% of its money from the child care development fund on certificates, when federal law requires them to use at least 70%.

MLICCI and others want MDHS to add to that by spending current and carryover TANF funds on child care subsidies for families that qualify for child care certificates. According to a memo MLICCI prepared, this method does not require legislative action, has no spending limit, and is already used by other states.

Under the current hold, families can apply and get their certificates renewed if they fall in one of the following six categories: on Temporary Assistance for Needy FamiliesTANF or transitioning off of TANF, homeless, with foster children, teen parents, deployed military, orand with special needs. The Division of Early Childhood Care & Development will continue paying for certificates for all families until their certificates expire.

In a statement, MDHS’ chief communications officer Mark Jones said “MDHS understands these concerns and reaffirms its commitment to support child care, transportation, education, and other needs of families who need to return or remain in the workforce. Our aim is to ensure our approaches are sustainable.”

Burnett, parent KyAsia Johnson, state Rep. Zakiya Summers, D-Jackson, and multiple child care providers talked about the toll the hold has taken on child care centers and families. They also stated the importance of child care to sustain the state’s workforce, keep child care providers afloat, and educate young children.

They also urged citizens to contact the state’s political leadership to get their attention.

“This decision is putting people like me in an impossible situation,” said Johnson, a child care provider and parent. “What am I supposed to do without child care?”

Each provider spoke about how they had to explain the hold to parents, many of whom have had to pull their children out of day care. Cantrell Keyes, director of Agape Christian Academy World in Jackson, had five families pull their children out of her center. “More than half of my school tuition comes from CCPP,” she said.

Rep. Summers called on MDHS to lift the hold on child care applications, use the extra TANF funds, and communicate better with parents and providers.

“Right now, thousands of Mississippi children might lose child care, not because the need has disappeared, but because the agency has made a choice,” she said.

The hold on child care certificates comes at a time when many child care providers and parents are struggling to stay afloat amid high costs, high turnover and high demand.

Deloris Suel, who owns Prep Company Tutorial Schools in Jackson, said, “Child care is in crisis. We’re not heading for crisis, we’re in crisis.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Tyler Perry comedy about a Mississippi lieutenant governor ‘She The People’ set to stream on Netflix

Netflix has announced it will stream “She The People,” a comedy written, produced and directed by Tyler Perry based on a fictional newly elected Mississippi Lieutenant Governor, Antoinette Dunkerson, played by Terri J. Vaughn.

According to a trailer released Thursday and press about the show, the new Lt. Gov. Dunkerson character realizes her new job will be extremely tough due to a sexist and condescending governor.

Executive producers for the show include Niya Palmer, Vaughn and former Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms. The cast also includes Tre Boyd, Dyon Brooks, Jade Nova, Jo Marie Payton and Drew Olivia Tillman.

The first eight-episode season debuts May 22 on Netflix, with a second eight-episode season premiering Aug. 14.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days agoJim talks with Rep. Robert Andrade about his investigation into the Hope Florida Foundation

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days agoOp-Ed: Colleges shouldn’t need remedial algebra classes: Five K-8 policy solutions to address math proficiency | Maryland

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days agoHighs in the upper 80s Saturday, backdoor cold front will cool us down a bit on Easter Sunday

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days agoValerie Storm Tracker

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days agoU.S. Supreme Court pauses deportations under wartime law

-

Mississippi Today5 days ago

Mississippi Today5 days ago‘Trainwreck on the horizon’: The costly pains of Mississippi’s small water and sewer systems

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days agoPrayer Vigil Held for Ronald Dumas Jr., Family Continues to Pray for His Return | April 21, 2025 | N

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed4 days agoMeteorologist Chita Craft is tracking a Severe Thunderstorm Warning that's in effect now