AP Photo/Mark Elias

Michael Petros, University of Illinois Chicago

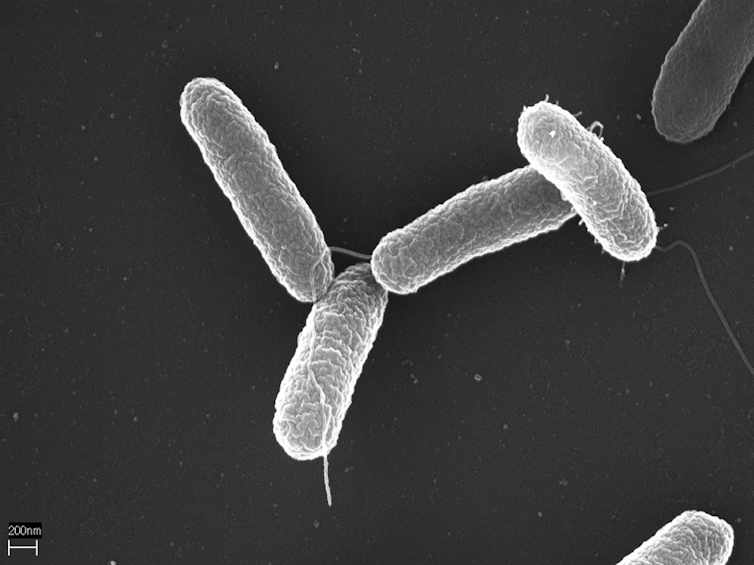

In 1985, contaminated milk in Illinois led to a Salmonella outbreak that infected hundreds of thousands of people across the United States and caused at least 12 deaths. At the time, it was the largest single outbreak of foodborne illness in the U.S. and remains the worst outbreak of Salmonella food poisoning in American history.

Many questions circulated during the outbreak. How could this contamination occur in a modern dairy farm? Was it caused by a flaw in engineering or processing, or was this the result of deliberate sabotage? What roles, if any, did politics and failed leadership play?

From my 50 years of working in public health, I’ve found that reflecting on the past can help researchers and officials prepare for future challenges. Revisiting this investigation and its outcome provides lessons on how food safety inspections go hand in hand with consumer protection and public health, especially as hospitalizations and deaths from foodborne illnesses rise.

Contamination, investigation and intrigue

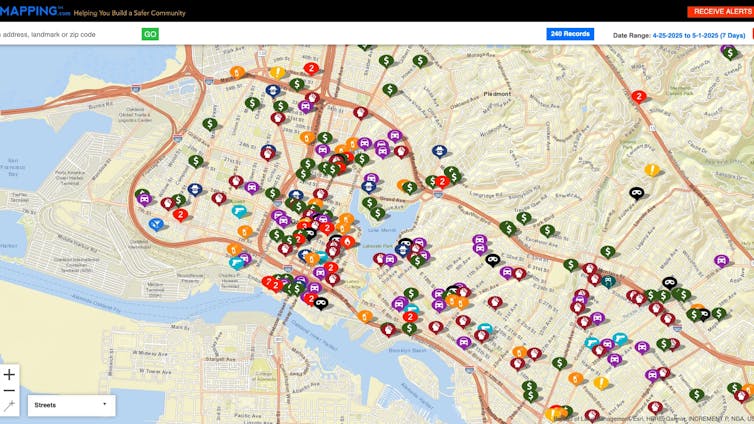

The Illinois Department of Public Health and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention led the investigation into the outbreak. The public health laboratories of the city of Chicago and state of Illinois were also closely involved in testing milk samples.

Investigators and epidemiologists from local, state and federal public health agencies found that specific lots of milk with expiration dates up to April 17, 1985, were contaminated with Salmonella. The outbreak may have been caused by a valve at a processing plant that allowed pasteurized milk to mix with raw milk, which can carry several harmful microorganisms, including Salmonella.

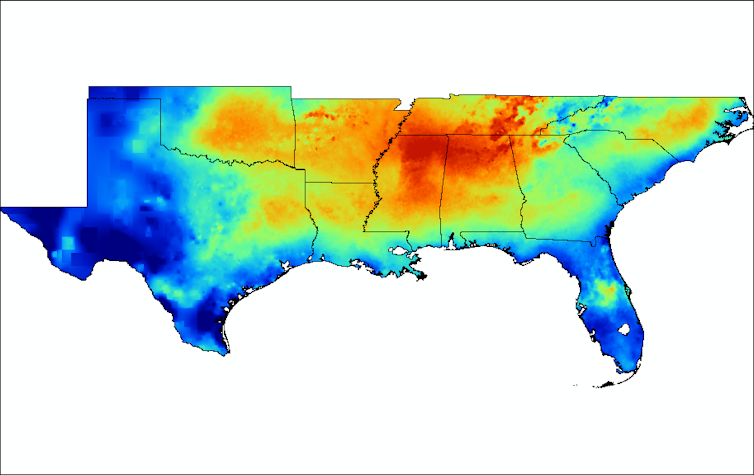

Overall, labs and hospitals in Illinois and five other Midwest states – Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin – reported over 16,100 cases of suspected Salmonella poisoning to health officials.

To make dairy products, skimmed milk is usually separated from cream, then blended back together in different levels to achieve the desired fat content. While most dairies pasteurize their products after blending, Hillfarm Dairy in Melrose Park, Illinois, pasteurized the milk first before blending it into various products such as skim milk and 2% milk.

Subsequent examination of the production process suggested that Salmonella may have grown in the threads of a screw-on cap used to seal an end of a mixing pipe. Investigators also found this strain of Salmonella 10 months earlier in a much smaller outbreak in the Chicago area.

Volker Brinkmann/Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology via PLoS One, CC BY-SA

Finding the source

The contaminated milk was produced at Hillfarm Dairy in Melrose Park, which was operated at the time by Jewel Companies Inc. During an April 3 inspection of the company’s plant, the Food and Drug Administration found 13 health and safety violations.

The legal fallout of the outbreak expanded when the Illinois attorney general filed suit against Jewel Companies Inc., alleging that employees at as many as 18 stores in the grocery chain violated water pollution laws when they dumped potentially contaminated milk into storm sewers. Later, a Cook County judge found Jewel Companies Inc. in violation of the court order to preserve milk products suspected of contamination and maintain a record of what happened to milk returned to the Hillfarm Dairy.

Political fallout also ensued. The Illinois governor at the time, James Thompson, fired the director of the Illinois Public Health Department when it was discovered that he was vacationing in Mexico at the onset of the outbreak and failed to return to Illinois. Notably, the health director at the time of the outbreak was not a health professional. Following this episode, the governor appointed public health professional and medical doctor Bernard Turnock as director of the Illinois Department of Public Health.

In 1987, after a nine-month trial, a jury determined that Jewel officials did not act recklessly when Salmonella-tainted milk caused one of the largest food poisoning outbreaks in U.S. history. No punitive damages were awarded to victims, and the Illinois Appellate Court later upheld the jury’s decision.

Lessons learned

History teaches more than facts, figures and incidents. It provides an opportunity to reflect on how to learn from past mistakes in order to adapt to future challenges. The largest Salmonella outbreak in the U.S. to date provides several lessons.

For one, disease surveillance is indispensable to preventing outbreaks, both then and now. People remain vulnerable to ubiquitous microorganisms such as Salmonella and E. coli, and early detection of an outbreak could stop it from spreading and getting worse.

Additionally, food production facilities can maintain a safe food supply with careful design and monitoring. Revisiting consumer protections can help regulators keep pace with new threats from new or unfamiliar pathogens.

Finally, there is no substitute for professional public health leadership with the competence and expertise to respond effectively to an emergency.![]()

Michael Petros, Clinical Assistant Professor of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences, University of Illinois Chicago

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.