Mississippi Today

Rankin sheriff says he learned at the knee of a former Simpson County sheriff, Lloyd ‘Goon’ Jones

The law enforcement official that Rankin County Sheriff Bryan Bailey regards as his mentor had a reputation for terrorizing Mississippi’s Black community.

His name? Lloyd Jones.

“Of all the law enforcement officers I have ever questioned, he was the most detestable,” said Constance Slaughter-Harvey, who served as an assistant secretary of state for Mississippi. As proof, she pointed to his 1970 deposition, where he repeatedly said “n—–” and then defended his use of the racist slur.

Now Sheriff Bailey is under Justice Department scrutiny for his office’s “Goon Squad,” which terrorized two Black men, hurled racial slurs at them, used a sex toy on them and shot one of them in the mouth.

On Nov. 30, The New York Times and the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting at Mississippi Today revealed a disturbing pattern of violence by Rankin County deputies stretching back two decades. Reporters reviewed dozens of allegations and corroborated 17 incidents involving 22 victims based on witness interviews, medical records, photographs of injuries and other documents.

The brutality harkened to the Jim Crow days when some law enforcement officers carried out violence in the name of preserving the Southern “way of life.”

Between 1956 and 1975, Lloyd Jones worked as an inspector at the Mississippi Highway Patrol. Civil rights leaders gave him the nickname “Goon,” and the nickname stuck.

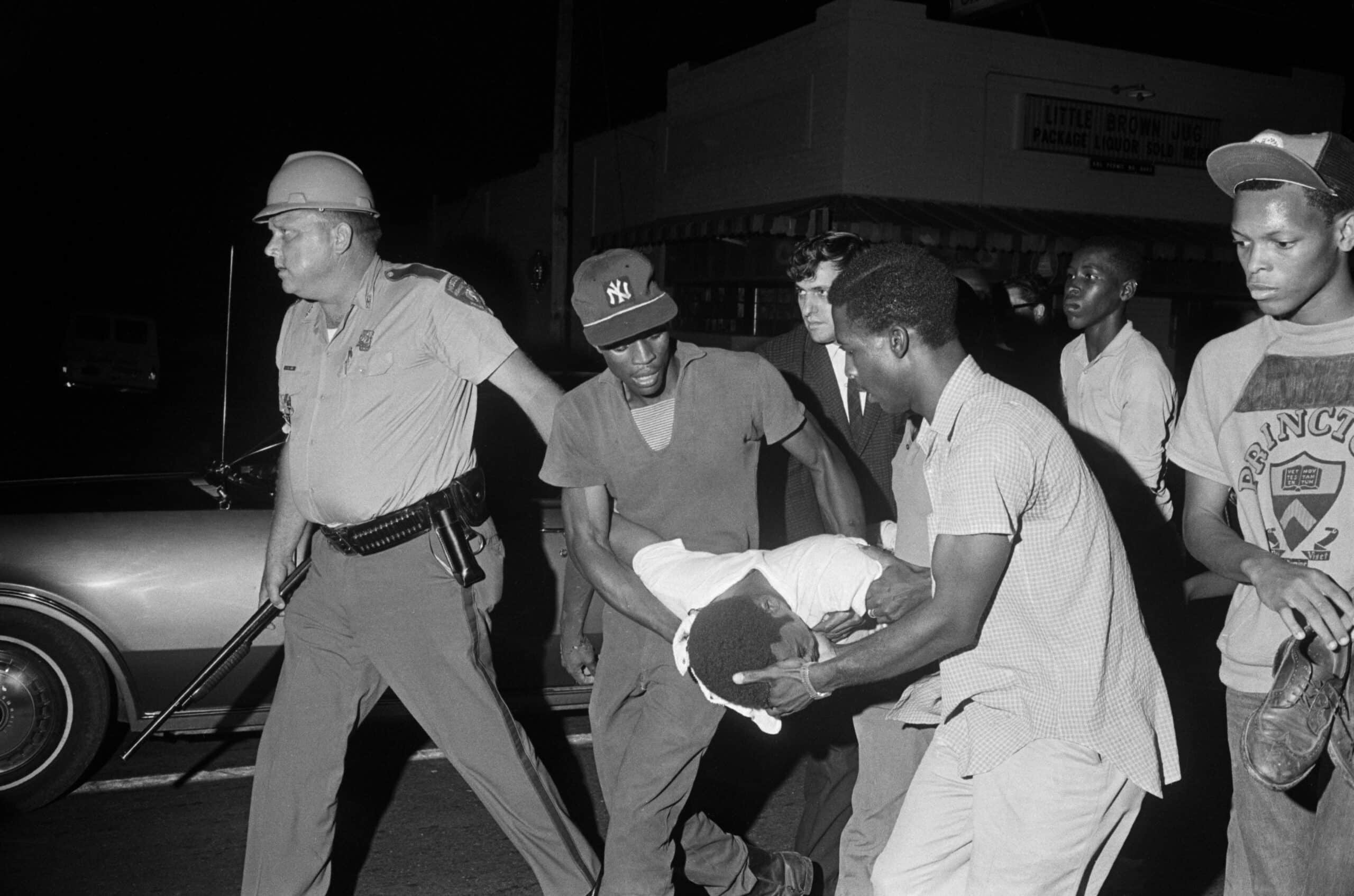

The Justice Department concluded that Jones killed Ben Brown in 1967. Brown, who had been involved in the civil rights movement, happened to walk past a standoff between law enforcement officers and protesters near the Jackson State University campus.

The FBI quoted Jones as telling a coworker that he killed “the n—–” with his 12-gauge shotgun, took it home, cleaned it, wrapped it in a blanket and hid it in his attic. He admitted in a sworn statement that he fired his shotgun 10 or 15 times that night.

Three years later, Jones was over state troopers who, along with Jackson police, responded to a protest on the Jackson State University campus. Law enforcement officers fired more than 400 rounds of ammunition in less than 30 seconds in every direction, many of them into a women’s dormitory.

Jones declared under oath that a sniper had fired at troopers before they unleashed their barrage of bullets, but journalists and some Jackson police officers testified they witnessed no such sniper fire.

By the time the gunfire ended, two young men were dead: Phillip Gibbs, a political science major who was married with two children, and James Green, a Jim Hill High School senior who was walking home from work. A dozen others were struck by bullets but survived.

When the Rev. John Perkins led activists on a Feb. 7, 1970, civil rights march in Simpson County, Jones had 14 troopers watching their every move, according to court documents.

Fellow activist Doug Huemmer was arrested on a charge of reckless driving. He said a trooper had already told him that if he didn’t leave Simpson County, “he would kill me.”

Troopers hauled Huemmer and other activists to the Rankin County Jail. When Perkins heard the news, he headed that way.

After arriving at the jail, Perkins and Huemmer said they and other activists were brutalized by then-Rankin County Sheriff Jonathan Edwards and other law enforcement officers. (An appeals court judge had already concluded that Edwards and his deputies beat Black Mississippians who attempted to vote.)

Huemmer said that, after one officer whacked him four times with a blackjack, he “saw stars” and fell to the floor.

While being held in a different room, Perkins said Jones kicked him and told him, “We could have killed you a long time ago.”

He said he balled up to protect himself from blows to his head and groin. One officer shoved a fork up his nose.

Perkins said another officer jammed a pistol against his head, and he thought he was going to die. The gun clicked.

The harassment didn’t stop after their release. Six months later, Huemmer was jailed in Rankin County again, this time after making a U-turn. He said the judge was going to let him go — until the judge found out he had been involved in the Mendenhall protest and ordered him put behind bars.

Huemmer said he and Perkins became victims, not just of “a racist paradigm,” but of the authority given to Southern sheriffs following the Civil War. “Sheriffs filled a power vacuum,” he said, “but the system rotted and became corrupt.”

In 1976, Jones became sheriff in Simpson County, where the Perkins’ family lived. A sense of fear and terror pervaded the Black community, said Perkins’ son, Derek. “People were afraid. They knew he could go inside their house and arrest them. I’ve seen that done.”

The FBI quoted Jones as saying, “Those n—–s don’t mess with me in Simpson County because they know I will put them in their place.”

Mary White, who served for decades as secretary for the Simpson County NAACP branch, described that time as “rough on Black people.”

The NAACP collected allegations of the beatings of Black Mississippians or of having drugs and guns tossed inside their cars, she said. “We got calls on a lot of different cases.”

Perkins’ daughter, Priscilla, recalled Jones entering their Simpson County home with two other white men just as dawn was breaking. Not knowing what else to do, she pretended to sleep.

News of a new “Goon Squad” has resurrected nightmares for the Perkins family.

“The Goon Squad was eerily similar to 53 years ago when Rankin County officers tortured my father and beat him in the Rankin County Jail in February 1970,” said Perkins’ daughter, Elizabeth. “The spirit of ‘Goon’ Jones lives on through the Goon Squad. We’ve got to break this Rankin County Goon Squad cycle.”

In the early 1990s, Bailey got his first job under Jones, who had survived a shooting a few years earlier. Deputy James Barnett was killed in the incident. In 1995, Jones became a murder victim.

After the slaying, Bailey appeared on television to praise his boss. “He worked seven days a week, 12 and 14 hours a day, and he wouldn’t ask us to do anything he wouldn’t do hisself [sic],” he said. “It’s an honor for me to work with him.”

Twenty years later, Bailey posted on Facebook that Jones was his mentor and wrote: “You had such an influence on my life and my career in law enforcement … you are no doubt a part of who I am and what I am today. I loved you like a father and I still miss you so much. I remember and use everything you taught me to this day.”

Slaughter-Harvey worked as one of the lawyers who brought the litigation against Jones. She still remembers the lawman glaring at her when she questioned him in Rev. Perkins’ lawsuit.

“He looked like he could kill me,” she said. “John Perkins forgave him, which is more than I can do. I can try to forgive him, but I can’t forget.”

In 2014 and 2015, a series of police pursuits of suspects from Rankin and other surrounding counties into the capital city made headlines after some car crashes led to injuries and deaths. Jackson Police Chief Lee Vance told the Clarion Ledger that “chasing people down busy streets during a busy time of day, pursuing misdemeanor suspects is something I don’t agree with.”

Jackson City Councilman Kenny Stokes drew national attention when he suggested that rocks, bricks and bottles be thrown at officers who chase misdemeanor suspects into Jackson.

Sheriff Bailey responded angrily that Rankin County citizens elected him “to keep them safe. That’s what we’re going to continue to do.”

He told Therese Apel, now CEO of Darkhorse Press, “The day’s not going to come where people think they can commit a crime in Rankin County and race back to Jackson …. We’re coming after ‘em. They started this. We didn’t. They came over here and committed a crime.”

He told Stokes to “keep those thugs over in the ward with him. … In my opinion, Kenny Stokes represents everything that is wrong with the city of Jackson and why it’s going downhill. … He says this is racism. Yes, it is racism — racism against every officer, against every deputy who bleeds blue. Just makes me sick for him to incite hatred and violence against the officers.”

Stokes is “standing behind his city limits in Jackson and talking all his big talk,” Bailey said. “I challenge him to cross this river, and I’ll drive my car over there and let him throw a rock at me. I’ll have him picking up trash on the side of the road for the next few years.”

He said if any Rankin County officer “gets hurt over there, we’re going to do our best to take everything he has — his state retirement, his paycheck and everything else.”

On Feb. 7, 2017, Bailey joined one of those chases after carjacking suspects and fired his gun into a fleeing vehicle. The bullet went through the rear passenger door and hit a teenager.

Former deputies say Sheriff Bailey remained obsessed with Braxton, a village of less than 200 where Jones once lived. Part of the community is in Rankin County and part of it is in Simpson County. Bailey grew up in the nearby village of Puckett, where he graduated high school in 1985.

Deputies had responded to a series of calls at 135 Conerly Road in Braxton involving aggravated assault, drug sales and a drug-related murder. That is the house where the Goon Squad later tortured the two Black men.

Brett McAlpin, chief investigator for the Rankin County Sheriff’s Department under Bailey, lived just a mile from that house. He had been involved in the investigation of the drug-related murder at that same house.

The charges that McAlpin and other officers have pleaded guilty to detailed what they did on Jan. 24 at that house.

That evening, a white neighbor told him several “suspicious” Black men had been staying at that four-bedroom home, which was owned by a white woman.

McAlpin asked Investigator Christian Dedmon to take care of it, and Dedmon reached out to a shift of officers known as “The Goon Squad,” because of “their willingness to use excessive force and not to report it,” according to the charges.

At 9:28 p.m. Dedmon texted three members of the Goon Squad, “Are y’all available for a mission?”

Because there was a chance of cameras, he told them to “work easy,” rather than kick the door down. Deputy Hunter Elward responded with an eyeroll emoji. Deputy Daniel Opdyke texted back an image of a crying baby.

Dedmon texted the group, “No bad mugshots,” greenlighting excessive force on the body that wouldn’t be captured in a photo.

After kicking in the carport door, they entered the house. They had no warrant.

Tasers are designed to incapacitate a suspect by transmitting a 50,000-volt electric shock. Deputies used them instead to torture Michael Jenkins and Eddie Parker after handcuffing them.

When Dedmon demanded that Parker tell him where the drugs were, Parker replied there were no drugs. Dedmon took out his gun and fired it into the wall.

Dedmon again demanded to know where the drugs were. Parker responded again that there were no drugs.

Deputies hurled racial slurs at the Black men, accused them of having sex with the white woman and told them to stay out of Rankin County and go back to majority-black Jackson.

When Opdyke found a dildo, he forced it into the mouth of Parker. But before he could do the same to Jenkins, Dedmon grabbed it and slapped the two Black men in the face with it and taunted them.

Dedmon also threatened to anally rape the men with the dildo, but stopped when he discovered Jenkins had defecated on himself.

Elward put his gun into Parker’s mouth and pulled the trigger. The unloaded gun clicked.

Elward racked the gun again, but when he pulled the trigger this time, the gun fired. The bullet lacerated Jenkins’ tongue and broke his jaw before exiting his face.

As Jenkins lay bleeding, officers huddled on the porch to devise a false story to cover up their crimes. They planted a gun next to Jenkins, claiming Elward shot Jenkins in self-defense.

McAlpin told Parker that if he stuck to the false story, he would be released from jail.

Richland narcotics investigator Joshua Hartfield threw the men’s soiled clothes into the woods behind the house. He also removed the hard drive from the home’s surveillance system and threw it into a creek in Florence.

Dedmon took meth that had yet to be entered into evidence and submitted it to the State Crime Lab as belonging to Parker.

McAlpin and Middleton told officers that if any of them revealed what happened, they would “kill them,” according to the charges.

Sentencing hearings for the five former deputies and the former Richland police officer are set for Jan. 18 and 19 in the U.S. District Court in Jackson.

After these guilty pleas, Sheriff Bailey denied he knew anything about the Goon Squad.

But he did know the background of the Goon Squad leader, Lt. Middleton, who pleaded guilty to culpable-negligence manslaughter for speeding at 98 mph in his patrol car without sirens or flashing lights before colliding with Desmonde Harris in 2005. A Hinds County judge awarded Harris’ family $500,000.

Sheriff Bailey also knew about McAlpin, whom several former deputies described as a “bully” known to “rough up” suspects. The Times and Mississippi Today interviewed more than 50 people who say they witnessed or experienced torture at the hands of the Rankin County Sheriff’s Department. The investigation found McAlpin was involved in at least 13 of the arrests and was repeatedly described by witnesses as leading the raids.

McAlpin was named in at least four lawsuits and six complaints going back to 2010, but that didn’t stop the sheriff from naming him “Investigator of the Year.”

Christian Dedmon shot up the ranks of the Rankin County Sheriff’s Department to become a narcotics investigator, despite his family background. His first cousin, Deryl Dedmon, is still serving 50 years in federal prison for a hate crime that ended with the beating and killing of a Black man, James C. Anderson, in 2011.

Deryl Dedmon was part of a group of 10 young people, all white, from Rankin County who conducted raids into Jackson, which they called “Jafrica.”

The FBI investigation showed that the raids into the capital city started with the beating of homeless men. When this white mob stumbled upon a Black man at a service station, they beat him mercilessly. One Black man at a golf course begged for his life.

“Like a lynching, for these young folk going out to ‘Jafrica’ was like a carnival outing,” said Carlton Reeves, the second Black federal judge in Mississippi history. “It was funny to them — an excursion which culminated in the death of innocent, African-American James Craig Anderson. On June 26, 2011, the fun ended.”

In sentencing Deryl Dedmon, Carlton Reeves described those raids: “ A toxic mix of alcohol, foolishness and unadulterated hatred caused these young people to resurrect the nightmarish specter of lynchings and lynch mobs from the Mississippi we long to forget.

“Like the marauders of ages past, these young folk conspired, planned, and coordinated a plan of attack on certain neighborhoods in the City of Jackson for the sole purpose of harassing, terrorizing, physically assaulting and causing bodily injury to black folk. They punched and kicked them about their bodies — their heads, their faces. They prowled. They came ready to hurt. They used dangerous weapons; they targeted the weak; they recruited and encouraged others to join in the coordinated chaos; and they boasted about their shameful activity. This was a 2011 version of the N—– hunts.”

The judge wondered aloud, “How could hate, fear or whatever it was that transformed genteel, God-fearing, God-loving Mississippians into mindless murderers and sadistic torturers?”

He had no answer.

Bailey worked in Simpson County alongside Paul Mullins, and the two teamed up again in Rankin County.

Mullins worked for 21 years in the Rankin County Sheriff’s Department under several different sheriffs.

After Bailey became sheriff in 2012, Mullins served as lieutenant over the late shift. The sheriff never asked him to do anything wrong or illegal, he said. “He let me run my shift.”

While working there, he never participated in any violence or witnessed any, he said. “My dad always told me to ‘do unto others as you would have them do unto you.’”

Mullins said the first time he ever heard anything about the Goon Squad was in August when Rankin County deputies pleaded guilty to charges. He called what happened “a black eye for everybody in Rankin County.”

In 2022, the late shift created challenge coins that read “Rankin County Sheriff’s Department” on one side and “Goon Squad” on the other, featuring a drawing of mobsters.

A deputy, who asked not to be named for fear of retribution, told Mississippi Today that Lt. Jeffrey Middleton, the lieutenant over the Goon Squad, ordered about 50 challenge coins.

“What they did set back law enforcement another 25 years,” the deputy said.

After Mullins was elected sheriff of Simpson County in 2019, Rankin County, at Bailey’s request, gave Mullins an unmarked 2019 Chevy Tahoe, a winch and a winch bumper, plus a Motorola mobile radio and a Motorola portable radio, according to the Dec. 26, 2019, minutes of the Rankin County Board of Supervisors.

Mullins also received a 9mm Glock, an AR-15 with a red dot scope, a Nikon Black Rangex 4K Laser Rangefinder and a Stihl chainsaw.

The cost to taxpayers? At least $75,000, according to prices for those items.

The justification for giving away these items: they were “surplus.”

Five days after Christmas in 2019, Clint Pennington slashed a nearly 7-inch gash in the back of his then-wife, Amanda, before cutting his own throat. (Pennington is the son of former Rankin County Sheriff Ronnie Pennington and the brother of Kristi Pennington Shanks, Sheriff Bailey’s girlfriend, who also serves as his administrative assistant.)

In 2022, Clint Pennington pleaded guilty to aggravated domestic violence, and the judge sentenced him to five years in prison. He is slated to be released in less than 18 months. Under Mississippi law, he could have received a sentence of up to 30 years.

Rather than being locked up in state prison, however, he is spending his days at the Simpson County Jail.

Mullins said he originally kept Pennington because “his daddy used to be sheriff and his wife was working at the Rankin County jail.”

Pennington hasn’t had any infractions since coming to the Simpson County Jail, Mullins said. “He works on the road crew.”

He said the Mississippi Department of Corrections asked him to house Pennington after his sentencing, presumably for safety reasons.

“Some people in the public think I’m doing it for Bryant Bailey,” he said, “but I would do it for anybody.”

Sheriff Bailey now faces his toughest challenge as sheriff: a federal investigation into his office.

At an Aug. 3 press conference following the officers’ guilty pleas to torturing Jenkins and Parker, the sheriff talked about how the crimes had hurt him. “I have 115 other deputies trying to keep this a safe county, trying to build a good reputation,” he said, “and they have robbed me of all of this.”

He shifted the blame to the officers. “My moral boundary is set by my Christian faith,” he said. “Do I cross that boundary? Sometimes I do. These guys were so far past any boundary that I know of. It’s unbelievable what they did. This is a bunch of criminals that did a home invasion.”

He acknowledged that he knew his deputies well. Asked how he didn’t know about them beating and torturing these two Black men, he replied, “The complaint has to come in. The reports have to come in. Something has to come in that I’ve been notified. That’s what I’ve got supervisors for.”

Under the sheriff’s system at the time, all complaints went to the supervisors. Two of those were McAlpin and Middleton, who have each pleaded guilty to federal charges in the Goon Squad’s activities.

Seven people told reporters they had mailed letters, filed formal complaints or called the sheriff personally to tell him about the abuse they experienced. One, a deputy of a neighboring county at the time, said the sheriff hung up on him.

Bailey disputed that he tolerates violence, saying, “If somebody comes back there [to jail] with a black eye, there better be an explanation.”

But the Times and Mississippi Today found at least seven jail mugshots that show injured people, including then-Hinds County Deputy Rick Loveday, who said jailers correctly guessed that McAlpin had beaten him up.

“How would they know,” Loveday asked, “unless a lot of people walked in looking like me?”

Bailey told reporters the only thing he’s guilty of is “trusting grown men that swore an oath to do their job correctly. I’m guilty of that.”

Informed that several high-ranking deputies were involved in arrests that had sparked accusations of brutal treatment, the sheriff replied, “I have 240 employees, there’s no way I can be with them each and every day.”

Former Mississippi Corrections Commissioner Robert L. Johnson, who previously served as police chief for the city of Jackson, called the sheriff’s response “a piss-poor excuse. You just can’t have that kind of activity and not be aware of it.”

Over the past two decades, nearly a dozen lawsuits have accused Rankin County deputies of brutality. Bailey, however, said he had no idea any such violence was taking place.

Johnson said he made sure he read every lawsuit filed against the Mississippi Department of Corrections so that he could know “what the hell is going on, and I was supervising 4,000 people instead of 240.”

Brian Howey, Nate Rosenfield and Ilyssa Daly contributed to this report. This article was reported in partnership with Big Local News at Stanford University and supported in part by a grant from the Pulitzer Center.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

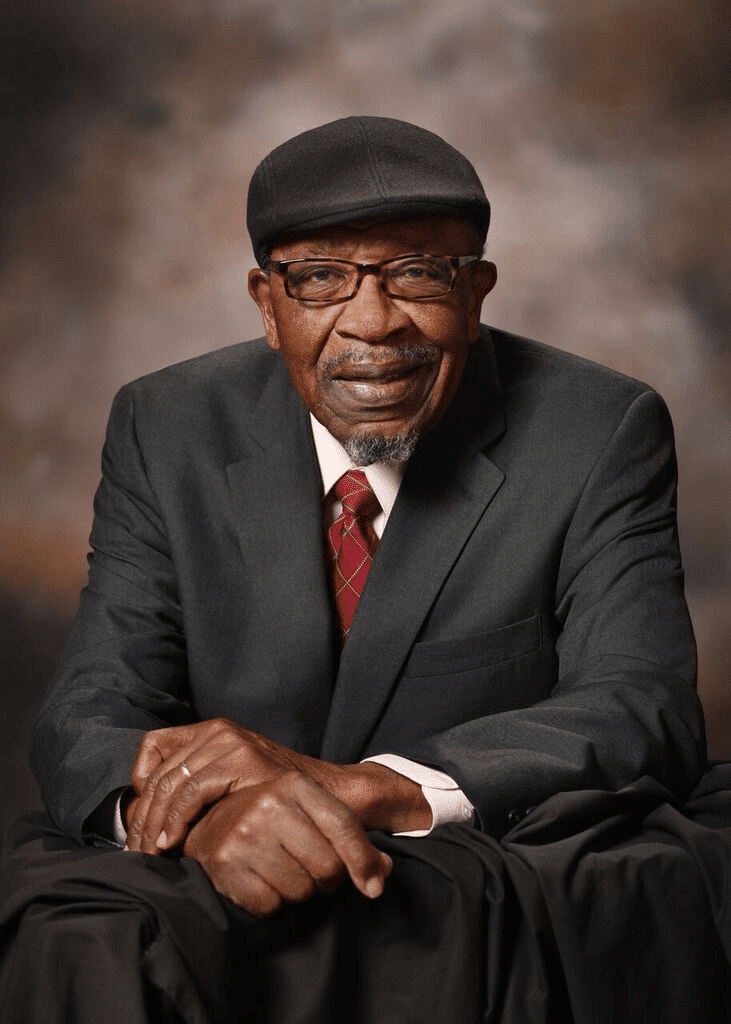

Meet Willye B. White: A Mississippian we should all celebrate

In an interview years and years ago, the late Willye B. White told me in her warm, soothing Delta voice, “A dream without a plan is just a wish. As a young girl, I had a plan.”

She most definitely did have a plan. And she executed said plan, as we shall see.

And I know what many readers are thinking: “Who the heck was Willye B. White?” That, or: “Willye B. White, where have I heard that name before?”

Well, you might have driven an eight-mile, flat-as-a-pancake stretch of U.S. 49E, between Sidon and Greenwood, and seen the marker that says: “Willye B. White Memorial Highway.” Or you might have visited the Olympic Room at the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and seen where White was a five-time participant and two-time medalist in the Summer Olympics as a jumper and a sprinter.

If you don’t know who Willye B. White was, you should. Every Mississippian should. So pour yourself a cup of coffee or a glass of iced tea, follow along and prepare to be inspired.

Willye B. White was born on the last day of 1939 in Money, near Greenwood, and was raised by grandparents. As a child, she picked cotton to help feed her family. When she wasn’t picking cotton, she was running, really fast, and jumping, really high and really long distances.

She began competing in high school track and field meets at the age of 10. At age 11, she scored enough points in a high school meet to win the competition all by herself. At age 16, in 1956, she competed in the Summer Olympics at Melbourne, Australia.

Her plan then was simple. The Olympics, on the other side of the world, would take place in November. “I didn’t know much about the Olympics, but I knew that if I made the team and I went to the Olympics, I wouldn’t have to pick cotton that year. I was all for that.”

Just imagine. You are 16 years old, a high school sophomore, a poor Black girl. You are from Money, Mississippi, and you walk into the stadium at the Melbourne Cricket Grounds to compete before a crowd of more than 100,000 strangers nearly 10,000 miles from your home.

She competed in the long jump. She won the silver medal to become the first-ever American to win a medal in that event. And then she came home to segregated Mississippi, to little or no fanfare. This was the year after Emmett Till, a year younger than White, was brutally murdered just a short distance from where she lived.

“I used to sit in those cotton fields and watch the trains go by,” she once told an interviewer. “I knew they were going to some place different, some place into the hills and out of those cotton fields.”

Her grandfather had fought in France in World War I. “He told me about all the places he saw,” White said. “I always wanted to travel and see the places he talked about.”

Travel, she did. In the late 1950s there were two colleges that offered scholarships to young, Black female track and field athletes. One was Tuskegee in Alabama, the other was Tennessee State in Nashville. White chose Tennessee State, she said, “because it was the farthest away from those cotton fields.”

She was getting started on a track and field career that would take her, by her own count, to 150 different countries across the globe. She was the best female long jumper in the U.S. for two decades. She competed in Olympics in Melbourne, Rome, Tokyo, Mexico City and Munich. She would compete on more than 30 U.S. teams in international events. In 1999, Sports Illustrated named her one of the top 100 female athletes of the 20th century.

Chicago became White’s home for most of adulthood. This was long before Olympic athletes were rich, making millions in endorsements and appearance fees. She needed a job, so she became a nurse. Later on, she became an public health administrator as well as a coach. She created the Willye B. White Foundation to help needy children with health and after school care.

In 1982, at age 42, she returned to Mississippi to be inducted into the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and was welcomed back to a reception at the Governor’s Mansion by Gov. William Winter, who introduced her during induction ceremonies. Twenty-six years after she won the silver medal at Melbourne, she called being hosted and celebrated by the governor of her home state “the zenith of her career.”

Willye B. White died of pancreatic cancer in a Chicago hospital in 2007. While working on an obituary/column about her, I talked to the late, great Ralph Boston, the three-time Olympic long jump medalist from Laurel. They were Tennessee State and U.S. Olympic teammates. They shared a healthy respect from one another, and Boston clearly enjoyed talking about White.

At one point, Ralph asked me, “Did you know Willye B. had an even more famous high school classmate.”

No, I said, I did not.

“Ever heard of Morgan Freeman?” Ralph said, laughing.

Of course.

“I was with Morgan one time and I asked him if he ever ran track,” Ralph said, already chuckling about what would come next.

“Morgan said he did not run track in high school because he knew if he ran, he’d have to run against Willye B. White, and Morgan said he didn’t want to lose to a girl.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Early voting proposal killed on last day of Mississippi legislative session

Mississippi will remain one of only three states without no-excuse early voting or no-excuse absentee voting.

Senate leaders, on the last day of their regular 2025 session, decided not to send a bill to Gov. Tate Reeves that would have expanded pre-Election Day voting options. The governor has been vocally opposed to early voting in Mississippi, and would likely have vetoed the measure.

The House and Senate this week overwhelmingly voted for legislation that established a watered-down version of early voting. The proposal would have required voters to go to a circuit clerk’s office and verify their identity with a photo ID.

The proposal also listed broad excuses that would have allowed many voters an opportunity to cast early ballots.

The measure passed the House unanimously and the Senate approved it 42-7. However, Sen. Jeff Tate, a Republican from Meridian who strongly opposes early voting, held the bill on a procedural motion.

Senate Elections Chairman Jeremy England chose not to dispose of Tate’s motion on Thursday morning, the last day the Senate was in session. This killed the bill and prevented it from going to the governor.

England, a Republican from Vancleave, told reporters he decided to kill the legislation because he believed some of its language needed tweaking.

The other reality is that Republican Gov. Tate Reeves strongly opposes early voting proposals and even attacked England on social media for advancing the proposal out of the Senate chamber.

England said he received word “through some sources” that Reeves would veto the measure.

“I’m not done working on it, though,” England said.

Although Mississippi does not have no-excuse early voting or no-excuse absentee voting, it does have absentee voting.

To vote by absentee, a voter must meet one of around a dozen legal excuses, such as temporarily living outside of their county or being over 65. Mississippi law doesn’t allow people to vote by absentee purely out of convenience or choice.

Several conservative states, such as Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas and Florida, have an in-person early voting system. The Republican National Committee in 2023 urged Republican voters to cast an early ballot in states that have early voting procedures.

Yet some Republican leaders in Mississippi have ardently opposed early voting legislation over concerns that it undermines election security.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

.

Mississippi Today

Mississippi Legislature approves DEI ban after heated debate

Mississippi lawmakers have reached an agreement to ban diversity, equity and inclusion programs and a list of “divisive concepts” from public schools across the state education system, following the lead of numerous other Republican-controlled states and President Donald Trump’s administration.

House and Senate lawmakers approved a compromise bill in votes on Tuesday and Wednesday. It will likely head to Republican Gov. Tate Reeves for his signature after it clears a procedural motion.

The agreement between the Republican-dominated chambers followed hours of heated debate in which Democrats, almost all of whom are Black, excoriated the legislation as a setback in the long struggle to make Mississippi a fairer place for minorities. They also said the bill could bog universities down with costly legal fights and erode academic freedom.

Democratic Rep. Bryant Clark, who seldom addresses the entire House chamber from the podium during debates, rose to speak out against the bill on Tuesday. He is the son of the late Robert Clark, the first Black Mississippian elected to the state Legislature since the 1800s and the first Black Mississippian to serve as speaker pro tempore and preside over the House chamber since Reconstruction.

“We are better than this, and all of you know that we don’t need this with Mississippi history,” Clark said. “We should be the ones that say, ‘listen, we may be from Mississippi, we may have a dark past, but you know what, we’re going to be the first to stand up this time and say there is nothing wrong with DEI.'”

Legislative Republicans argued that the measure — which will apply to all public schools from the K-12 level through universities — will elevate merit in education and remove a list of so-called “divisive concepts” from academic settings. More broadly, conservative critics of DEI say the programs divide people into categories of victims and oppressors and infuse left-wing ideology into campus life.

“We are a diverse state. Nowhere in here are we trying to wipe that out,” said Republican Sen. Tyler McCaughn, one of the bill’s authors. “We’re just trying to change the focus back to that of excellence.”

The House and Senate initially passed proposals that differed in who they would impact, what activities they would regulate and how they aim to reshape the inner workings of the state’s education system. Some House leaders wanted the bill to be “semi-vague” in its language and wanted to create a process for withholding state funds based on complaints that almost anyone could lodge. The Senate wanted to pair a DEI ban with a task force to study inefficiencies in the higher education system, a provision the upper chamber later agreed to scrap.

The concepts that will be rooted out from curricula include the idea that gender identity can be a “subjective sense of self, disconnected from biological reality.” The move reflects another effort to align with the Trump administration, which has declared via executive order that there are only two sexes.

The House and Senate disagreed on how to enforce the measure but ultimately settled on an agreement that would empower students, parents of minor students, faculty members and contractors to sue schools for violating the law.

People could only sue after they go through an internal campus review process and a 25-day period when schools could fix the alleged violation. Republican Rep. Joey Hood, one of the House negotiators, said that was a compromise between the chambers. The House wanted to make it possible for almost anyone to file lawsuits over the DEI ban, while Senate negotiators initially bristled at the idea of fast-tracking internal campus disputes to the legal system.

The House ultimately held firm in its position to create a private cause of action, or the right to sue, but it agreed to give schools the ability to conduct an investigative process and potentially resolve the alleged violation before letting people sue in chancery courts.

“You have to go through the administrative process,” said Republican Sen. Nicole Boyd, one of the bill’s lead authors. “Because the whole idea is that, if there is a violation, the school needs to cure the violation. That’s what the purpose is. It’s not to create litigation, it’s to cure violations.”

If people disagree with the findings from that process, they could also ask the attorney general’s office to sue on their behalf.

Under the new law, Mississippi could withhold state funds from schools that don’t comply. Schools would be required to compile reports on all complaints filed in response to the new law.

Trump promised in his 2024 campaign to eliminate DEI in the federal government. One of the first executive orders he signed did that. Some Mississippi lawmakers introduced bills in the 2024 session to restrict DEI, but the proposals never made it out of committee. With the national headwinds at their backs and several other laws in Republican-led states to use as models, Mississippi lawmakers made plans to introduce anti-DEI legislation.

The policy debate also unfolded amid the early stages of a potential Republican primary matchup in the 2027 governor’s race between State Auditor Shad White and Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann. White, who has been one of the state’s loudest advocates for banning DEI, had branded Hosemann in the months before the 2025 session “DEI Delbert,” claiming the Senate leader has stood in the way of DEI restrictions passing the Legislature.

During the first Senate floor debate over the chamber’s DEI legislation during this year’s legislative session, Hosemann seemed to be conscious of these political attacks. He walked over to staff members and asked how many people were watching the debate live on YouTube.

As the DEI debate cleared one of its final hurdles Wednesday afternoon, the House and Senate remained at loggerheads over the state budget amid Republican infighting. It appeared likely the Legislature would end its session Wednesday or Thursday without passing a $7 billion budget to fund state agencies, potentially threatening a government shutdown.

“It is my understanding that we don’t have a budget and will likely leave here without a budget. But this piece of legislation …which I don’t think remedies any of Mississippi’s issues, this has become one of the top priorities that we had to get done,” said Democratic Sen. Rod Hickman. “I just want to say, if we put that much work into everything else we did, Mississippi might be a much better place.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

-

Mississippi Today3 days ago

Mississippi Today3 days agoPharmacy benefit manager reform likely dead

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days agoTornado watch, severe thunderstorm warnings issued for Oklahoma

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days agoGeorgia road project forcing homeowners out | FOX 5 News

-

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed7 days agoHometown Hero | Restaurant owner serves up hope

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed4 days agoTornado practically rips Bullitt County barn in half with man, several animals inside

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days agoBudget cuts: Senior Citizens Inc. and other non-profits worry for the future

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoStrangers find lost family heirloom at Cocoa Beach

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days agoUpdate: 4 arrested during drug roundup in Logan County