Mississippi Today

Rankin ‘Goon Squad’ of law officers admit to hindering prosecution in torture case

Six white former law enforcement officers pleaded guilty to hindering prosecution in their torturing of two Black men as part of a “Goon Squad” operation aimed at getting African Americans to “go back” to the predominantly Black city of Jackson.

“To my knowledge,” said Trent Walker, the attorney for the two men, “never in the history of Mississippi have, in particular, white officers been held to account for brutality against Black victims.”

On the evening of Jan. 24, five Rankin County deputies and a Richland police officer beat and tortured the handcuffed Black men, Eddie Parker and Michael Jenkins, hurled racial slurs at them, accused them of “taking advantage” of the white female homeowner and warned them to stay out of Rankin County.

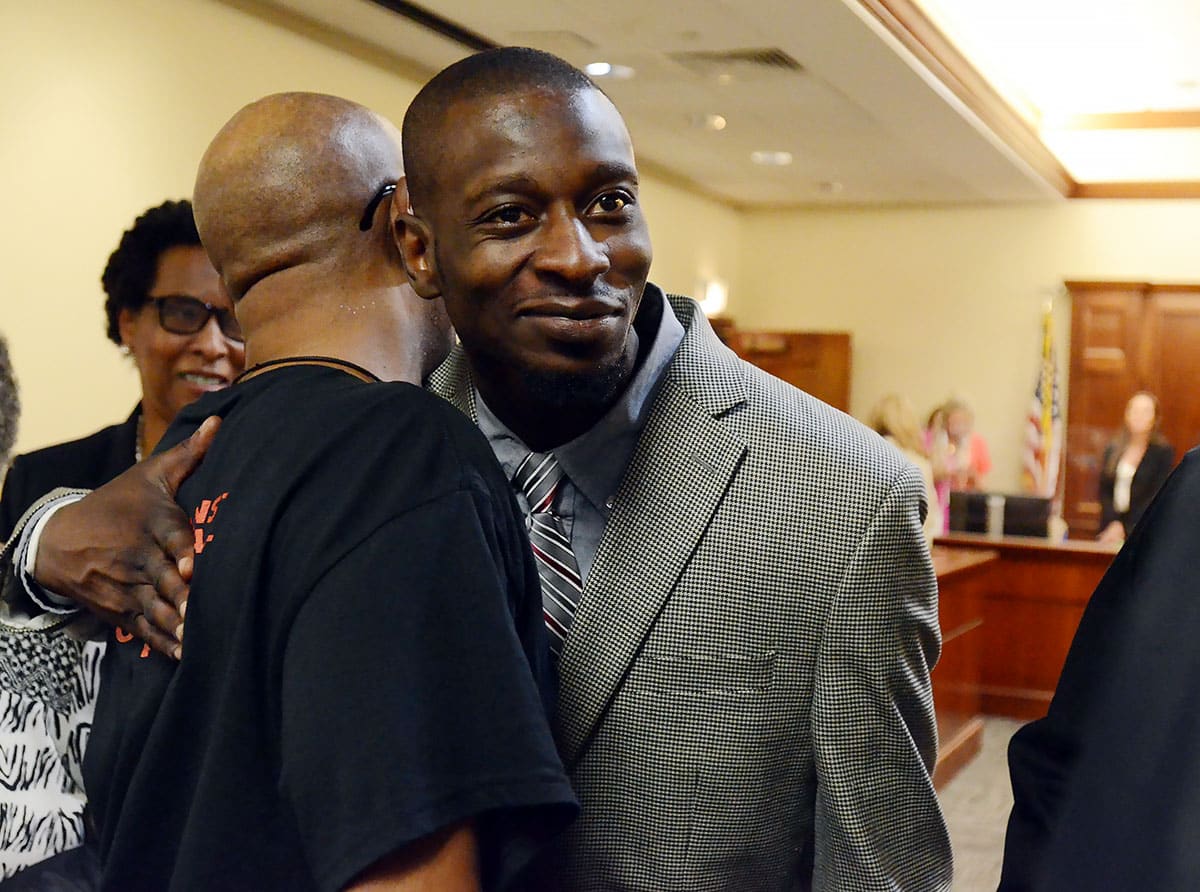

On Monday, Parker and Jenkins sat in a Rankin County courthouse and watched as the former law enforcement officers pleaded guilty. Afterward, Parker said, “I hope this is a lesson to everybody out there. Justice will be served.”

They included former patrol deputy Hunter Elward, who shot Jenkins in the mouth, Brett McAlpin, who served as chief investigator for the sheriff’s office, Lt. Jeffrey Middleton, who supervised the “Goon Squad” shift, Christian Dedmon, who served as a narcotics investigator, Daniel Opdyke, who served as a patrol deputy, Josh Hartfield, who served as narcotics investigator for Richland Police Department.

Prosecution recommendations included these sentences: Elward, 15 years in prison; Dedmon, 10 years; McAlpin and Middleton, eight years; Opdyke and Hartfield, five years. No date has been set for their sentencings.

The officers previously pleaded guilty to multiple federal charges related to the beating, torture, unwarranted search and coverup. Sentencing hearings are set for mid-November.

On the evening of Jan. 24, a white neighbor informed McAlpin that “several Black males” were living in the home of a white woman in the neighborhood. According to the criminal information, the neighbor claimed he had seen “suspicious behavior” in the home.

McAplin ordered Dedmon to investigate. Dedmon texted fellow members of the Goon Squad, nicknamed because of the group’s willingness to beat people up during arrests.

“Are y’all available for a mission?” Dedmon texted, warning the officers that they might have to “work easy”— knocking on the men’s door instead of kicking it down — because the home was equipped with security cameras. Patrol deputy Daniel Opdyke texted back a gif of a baby crying.

Dedmon texted “no bad mugshots” signaling that they should beat the men on parts of their body that wouldn’t show up in a mugshot, according to the criminal information.

Officers crept onto the property, surrounding the doors at the side and the back of the house, which lacked security cameras. Then, without a warrant, they kicked the doors down.

The officers shouted orders that the two men complied with, according to the criminal information. Dedmon handcuffed them and — without seeing any evidence of a crime — began to tase them repeatedly. Opdyke kicked Parker in the ribs.

Officer Dedmon asked the men where their drugs were. When Parker and Jenkins replied that they didn’t have drugs, Dedmon shot a bullet into the wall, demanding that they confess.

The officers accused the two men of taking advantage of the white woman who owned the home, according to the criminal information, calling them “n—–,” “monkey” and “boy.”

When the officers searched the home, Opdyke found a dildo in one of the bedrooms, which he gave to Dedmon, who used it to slap the men. Dedmon stuck the sex toy in their mouths and turned Jenkins on his back threatening to anally rape him with it. Dedmon only stopped when he noticed Jenkins had defecated on himself.

Dedmon then began to taunt the men, pouring milk, alcohol and chocolate syrup onto their faces and into their mouths. He poured cooking grease on Parker’s head, while Elward threw eggs at the men.

Jenkins and Parker were forced to strip naked, shower and change their clothes to destroy evidence of the abuse.

Then the two men were beaten with objects around the home — a piece of wood, a kitchen utensil, a metal sword — and tased repeatedly.

McAlpin and Lt. Jeffrey Middleton, who supervised the Goon Squad, stole two rubber bar mats from the home and were about to take a Class A military uniform, when they heard shots ring out, according to the federal criminal information.

The first shot was fired by Dedmon into the yard. The second was fired by Elward, who meant to perform a mock execution, secretly removing a bullet from the chamber of his service pistol before “dry firing” into Jenkin’s mouth. He tried to repeat the intimidation tactic, but this time the weapon fired, tearing a bullet through Jenkin’s tongue and jaw.

Without providing medical attention to Jenkins, who was bleeding on the floor, the officers devised an elaborate cover up. Middleton planted a “throw down” gun he kept in his car in the home, and Dedmon took meth from a previous drug bust, which he neglected to enter into evidence, and later submitted it to the crime, stating that it belonged to Jenkins.

The officers disposed of any shell casings they could find and threw the men’s clothes into the woods behind the house. They stole the hard drive from the home’s surveillance system and later threw it in a creek in Florence. McAlpin and Middleton, the two highest ranking officers, threatened to kill the other deputies if they said a word, according to court records.

Jenkins was taken to the hospital and received life-saving surgeries. He was charged with disorderly conduct, assaulting an officer and drug possession. Parker was taken to jail and charged with possession of drug paraphernalia and disorderly conduct. All charges were later dismissed.

Elward signed an affidavit, claiming Jenkins had shot at him and the other officers filed false police reports and lied to investigators from the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation to back up Elward’s claims.

Under their federal convictions, Dedmon and Elward each face up to 120 years in prison, plus a life sentence. Opdyke faces up to 100 years; McAlpin, up to 90 years; Hartfield and Middleton, up to 80 years each.

Seth W. Stoughton, law enforcement expert and professor at the University of South Carolina School of Law, called the acts “reminiscent of the most blatant racist abuses by police in the Jim Crow and Civil Rights era. This was a lynch mob of officers, pure and simple.”

The environment enabled the Goon Squad to operate, he said. “An investigator knew exactly who to call, and they knew exactly how to communicate to do something like this,” he said. “That’s not spontaneous, it’s the result of the tacit or explicit approval of the supervisors and agency.”

But Sheriff Bryan Bailey, who arrived at the scene an hour and a half after the officers were first dispatched, told reporters that the deputies lied to him.

“I am sick to my stomach,” he told reporters. “I have tried to build a reputation, tried to have a safe county. They have robbed me of all of this.”

Jenkins’ mother, Mary, said the officers “feel comfortable telling the same lie over and over again.”

UPDATE 8/14,2023: This story has been updated to include additional comments.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=276889

Mississippi Today

1964: Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was formed

April 26, 1964

Civil rights activists started the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to challenge the state’s all-white regular delegation to the Democratic National Convention.

The regulars had already adopted this resolution: “We oppose, condemn and deplore the Civil Rights Act of 1964 … We believe in separation of the races in all phases of our society. It is our belief that the separation of the races is necessary for the peace and tranquility of all the people of Mississippi, and the continuing good relationship which has existed over the years.”

In reality, Black Mississippians had been victims of intimidation, harassment and violence for daring to try and vote as well as laws passed to disenfranchise them. As a result, by 1964, only 6% of Black Mississippians were permitted to vote. A year earlier, activists had run a mock election in which thousands of Black Mississippians showed they would vote if given an opportunity.

In August 1964, the Freedom Party decided to challenge the all-white delegation, saying they had been illegally elected in a segregated process and had no intention of supporting President Lyndon B. Johnson in the November election.

The prediction proved true, with white Mississippi Democrats overwhelmingly supporting Republican candidate Barry Goldwater, who opposed the Civil Rights Act. While the activists fell short of replacing the regulars, their courageous stand led to changes in both parties.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Mississippi River flooding Vicksburg, expected to crest on Monday

Warren County Emergency Management Director John Elfer said Friday floodwaters from the Mississippi River, which have reached homes in and around Vicksburg, will likely persist until early May. Elfer estimated there areabout 15 to 20 roads underwater in the area.

“We’re about half a foot (on the river gauge) from a major flood,” he said. “But we don’t think it’s going to be like in 2011, so we can kind of manage this.”

The National Weather projects the river to crest at 49.5 feet on Monday, making it the highest peak at the Vicksburg gauge since 2020. Elfer said some residents in north Vicksburg — including at the Ford Subdivision as well as near Chickasaw Road and Hutson Street — are having to take boats to get home, adding that those who live on the unprotected side of the levee are generally prepared for flooding.

“There are a few (inundated homes), but we’ve mitigated a lot of them,” he said. “Some of the structures have been torn down or raised. There are a few people that still live on the wet side of the levee, but they kind of know what to expect. So we’re not too concerned with that.”

The river first reached flood stage in the city — 43 feet — on April 14. State officials closed Highway 465, which connects the Eagle Lake community just north of Vicksburg to Highway 61, last Friday.

Elfer said the areas impacted are mostly residential and he didn’t believe any businesses have been affected, emphasizing that downtown Vicksburg is still safe for visitors. He said Warren County has worked with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency to secure pumps and barriers.

“Everybody thus far has been very cooperative,” he said. “We continue to tell people stay out of the flood areas, don’t drive around barricades and don’t drive around road close signs. Not only is it illegal, it’s dangerous.”

NWS projects the river to stay at flood stage in Vicksburg until May 6. The river reached its record crest of 57.1 feet in 2011.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

With domestic violence law, victims ‘will be a number with a purpose,’ mother says

Joslin Napier. Carlos Collins. Bailey Mae Reed.

They are among Mississippi domestic violence homicide victims whose family members carried their photos as the governor signed a bill that will establish a board to study such deaths and how to prevent them.

Tara Gandy, who lost her daughter Napier in Waynesboro in 2022, said it’s a moment she plans to tell her 5-year-old grandson about when he is old enough. Napier’s presence, in spirit, at the bill signing can be another way for her grandson to feel proud of his mother.

“(The board) will allow for my daughter and those who have already lost their lives to domestic violence … to no longer be just a number,” Gandy said. “They will be a number with a purpose.”

Family members at the April 15 private bill signing included Ashla Hudson, whose son Collins, died last year in Jackson. Grandparents Mary and Charles Reed and brother Colby Kernell attended the event in honor of Bailey Mae Reed, who died in Oxford in 2023.

Joining them were staff and board members from the Mississippi Coalition Against Domestic Violence, the statewide group that supports shelters and advocated for the passage of Senate Bill 2886 to form a Domestic Violence Facility Review Board.

The law will go into effect July 1, and the coalition hopes to partner with elected officials who will make recommendations for members to serve on the board. The coalition wants to see appointees who have frontline experience with domestic violence survivors, said Luis Montgomery, public policy specialist for the coalition.

A spokesperson from Gov. Tate Reeves’ office did not respond to a request for comment Friday.

Establishment of the board would make Mississippi the 45th state to review domestic violence fatalities.

Montgomery has worked on passing a review board bill since December 2023. After an unsuccessful effort in 2024, the coalition worked to build support and educate people about the need for such a board.

In the recent legislative session, there were House and Senate versions of the bill that unanimously passed their respective chambers. Authors of the bills are from both political parties.

The review board is tasked with reviewing a variety of documents to learn about the lead up and circumstances in which people died in domestic violence-related fatalities, near fatalities and suicides – records that can include police records, court documents, medical records and more.

From each review, trends will emerge and that information can be used for the board to make recommendations to lawmakers about how to prevent domestic violence deaths.

“This is coming at a really great time because we can really get proactive,” Montgomery said.

Without a board and data collection, advocates say it is difficult to know how many people have died or been injured in domestic-violence related incidents.

A Mississippi Today analysis found at least 300 people, including victims, abusers and collateral victims, died from domestic violence between 2020 and 2024. That analysis came from reviewing local news stories, the Gun Violence Archive, the National Gun Violence Memorial, law enforcement reports and court documents.

Some recent cases the board could review are the deaths of Collins, Napier and Reed.

In court records, prosecutors wrote that Napier, 24, faced increased violence after ending a relationship with Chance Fabian Jones. She took action, including purchasing a firearm and filing for a protective order against Jones.

Jones’s trial is set for May 12 in Wayne County. His indictment for capital murder came on the first anniversary of her death, according to court records.

Collins, 25, worked as a nurse and was from Yazoo City. His ex-boyfriend Marcus Johnson has been indicted for capital murder and shooting into Collins’ apartment. Family members say Collins had filed several restraining orders against Johnson.

Johnson was denied bond and remains in jail. His trial is scheduled for July 28 in Hinds County.

He was a Jackson police officer for eight months in 2013. Johnson was separated from the department pending disciplinary action leading up to immediate termination, but he resigned before he was fired, Jackson police confirmed to local media.

Reed, 21, was born and raised in Michigan and moved to Water Valley to live with her grandparents and help care for her cousin, according to her obituary.

Kylan Jacques Phillips was charged with first degree murder for beating Reed, according to court records. In February, the court ordered him to undergo a mental evaluation to determine if he is competent to stand trial, according to court documents.

At the bill signing, Gandy said it was bittersweet and an honor to meet the families of other domestic violence homicide victims.

“We were there knowing we are not alone, we can travel this road together and hopefully find ways to prevent and bring more awareness about domestic violence,” she said.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days agoJim talks with Rep. Robert Andrade about his investigation into the Hope Florida Foundation

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoPrayer Vigil Held for Ronald Dumas Jr., Family Continues to Pray for His Return | April 21, 2025 | N

-

Mississippi Today5 days ago

Mississippi Today5 days ago‘Trainwreck on the horizon’: The costly pains of Mississippi’s small water and sewer systems

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days agoMeteorologist Chita Craft is tracking a Severe Thunderstorm Warning that's in effect now

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed4 days agoTrump touts manufacturing while undercutting state efforts to help factories

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed5 days agoTaking video of military bases using drones could be outlawed | Virginia

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days agoNo. 3 Texas walks off No. 9 LSU again to capture crucial SEC softball series

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed4 days agoFederal report due on Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina’s path to recognition as a tribal nation