Mississippi Today

Q&A: Jackson’s Springboard to Opportunities director on what the nonprofit learned from putting cash into low-income mothers’ hands

Q&A: Jackson’s Springboard to Opportunities director on what the nonprofit learned from putting cash into low-income mothers’ hands

Sarah Stripp is the managing director of Jackson-based nonprofit Springboard to Opportunities, which supports low-income Mississippians. During the water crisis, when families couldn’t rely on clean water from their own pipes, Stripp’s organization was giving households $150 a month to buy bottled water. The group is best known for its guaranteed income program, Magnolia Mother’s Trust. Stripp sat down with reporter Sara DiNatale to talk about her work and what the group’s learned entering its fifth year of the income program.

The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Sara DiNatale: Well, first off, if you could just tell me a little bit about your nonprofit, Springboard to Opportunities, and all of the types of things you do and the type of gaps that you try to help fill for women in Jackson?

Stripp: So we are an organization that works with families who live in federally subsidized housing, and provide programs and services to help them meet their goals. So subsidized housing, particularly in Mississippi is like 99%, headed by single women and about 99% of those families are Black.

So while technically, our mission is to reach families, and affordable housing, it tends to be Black mothers who are kind of like the main recipients of our work. We really started in 2013 as a resident-service provider. We were basically contracted by private developers to come and provide additional services to families in affordable housing. So that could be everything from providing housing stability, helping folks if they’re behind on rent and trying to figure out some different resources, or making sure that they’re able to keep up their apartments. Then, having things they need for that, too, like helping folks get childcare or providing after school programs, workforce support programs or different things like that.

And so we work really closely with community members themselves to actually tell us what it is that they need, as opposed to coming in and deciding for them what they need. Because we believe families know better than anybody else what it is that they need in order to thrive and meet their goals.

DiNatale: So, what do they need? And how has that turned into programs that you offer?

Stripp: As we would design programming, we would do that hand-in-hand with community members and do our best to make sure that it was lining up with what they were asking for. And at the same time, we also really recognize that programming can only do so much. And at the end of the day, if there’s not good policies to support families, nothing’s going to change.

It was through some of that work, and through conversations that we were having with families, where we kept hearing them say: ‘You know, what I actually need to reach my goal is not like another program or another thing that I have to attend, right? It’s cash … Food stamps are only going to cover food. My housing voucher only covers housing. I also need diapers; I also need transportation; I also need childcare. I need all these other things. If I’m trying to do that, I need the freedom to be able to spend cash in the way that I see fit for me and my family, as opposed to in the way that a government voucher has decided I should spend it.’

So from that, we wanted to really honor our mission and who we are as an organization and said, ‘OK, so let’s figure out how we’re going to do that.’ So we started a small pilot in 2018, with 20 black mothers called the Magnolia Mother’s Trust, which was really the first guaranteed income program … that launched in the country.

DiNatale: So how does the program work and what did you see start to happen?

Stripp: We were working at that point (in 2018) with just 20 moms who received $1,000 a month for 12 months with no strings attached … to see what would happen. And just to kind of put it out there … When moms get money, they spend it to support their families.

Whether that was being able to go back to school or move to a higher paying job, moving out of affordable housing, being able to take their kids to see their grandfather for the first time or some families went down to the beach for the first time and were able to take vacations. One mom bought her son a tuba so that he could be in the marching band. (It was) these little things that moms have always wanted to provide for their kids.

We were able to get some really good traction from that early pilot. And then we were able to expand that in the next year to about 110 moms. Actually, each year since, we’ve had about 100 moms go through a cohort of getting $1,000 a month for 12 months. And then we’ve added in, in addition to that, a $1,000 deposit and in a 529 (college) savings account for their kids so that they’re having the opportunity to build some wealth for their children.

We also have this opportunity to make sure that the stories of our moms are being put out there. We knew nothing was going to be able to change at a federal or state policy level if we continue to operate with … whatever these kind of nasty narratives around moms who are on welfare, that they’re going to abuse the system or that they don’t know what they’re doing with their money.

DiNatale: What are some of the expectations that you had going into the pilot? Were those met, exceeded or different than what the actual outcome was? What did you really wind up learning?

Stripp: We didn’t have a whole lot of expectations, because we wanted to leave the doors open. We were really asking questions around: When you give moms cash do they have the breathing room and the space to be able to actually think about their goals and what they want to do?

They have time to step back and take some time to go back to school and work on the career that they really wanted, as opposed to running between three part-time jobs just trying to make ends meet … People are able to save some of this money and move out of affordable housing or move into a higher paying career.

I think everything got really complicated with the second cohort because COVID came in, and it changed everything. On top of COVID, we just kind of have these compounding crises – the water crisis – and folks losing jobs because of that, because they’ve had to stay home with their kids (when classes went remote online).

But at the same time, I think what we really have seen … particularly in the second, third, and now we’re just about to wrap up our fourth cohort, what’s come out and all of the different kinds of evaluations and pieces that we’ve done has been a really increased sense of parental efficacy. So, moms feeling like they’re able to be the moms that they want to be for the first time. It’s a really big growth in their own sense of agency and their own sense of self-confidence.

DiNatale: I know a report is coming out later this month that covers more deeply what you’ve learned through this process. But with that work done, and lessons learned, is the plan to continue this program?

Stripp: We’re committed to at least having one more cohort that will start later this fall. I think there might be some pieces that look a little bit different based on things that we’ve learned, but we’re still kind of fleshing out a lot of those details. We want to at least do it once more. What we had committed to, at the beginning, was five years.

Ultimately, what we know is that we are a drop in the bucket. We are providing something for a subset of moms here in Jackson. And that’s important, but it’s not enough. And even the length of the program that we’re able to do is not enough. And I think all of these pilots that we’re seeing, a lot of people are using (American Rescue Plan Act) funds and other things to be able to do these (types of programs) in different cities, that’s great. But again, it’s never going to be totally what we want to see.

Our goal has always been, and what we’ve always said from the beginning, was to actually change federal policy and be able to see something come out of this — where we are creating more cash and trust-based benefits for families as opposed to limited vouchers or a social safety net that’s really easy to fall through.

DiNatale: So your goal, really, is changing the way America treats welfare and assistance programs. With the situation of the Mississippi welfare scandal in mind – the alleged misuse of $77 million in TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) funds – have you seen the conversation change at all about welfare dollar use?

Stripp: I would say no, not on a community level. Before we actually started doing the Magnolia Mother’s Trust, we had done an ad before the welfare scandal…came out, and in about 2017, we did a paper with (public policy think tank) New America, and interviewed a lot of our moms to talk about TANF…And I think, at that point, that was when less than 2% of applications were even being seen. And when we talked to moms about TANF and welfare their response was always like, ‘Oh, I don’t even bother with that; it’s not even worth my time.’ They had either applied before or tired before and it just never made sense. So most of them felt so kind of disillusioned by the system to begin with.

DiNatale: What about state leadership? Has anyone responded to the idea of changing how assistance works?

Stripp: I would say in Mississippi, no. The players at the table who we know would be into this are into it, and the players who are not into it are not interested. The (Mississippi) Democratic Caucus has been really supportive. We had moms come and testify, like the TANF legislative hearings … We’ve tried to have some conversations with the Department of Human Services that haven’t really gone anywhere.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

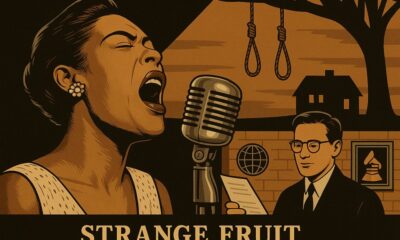

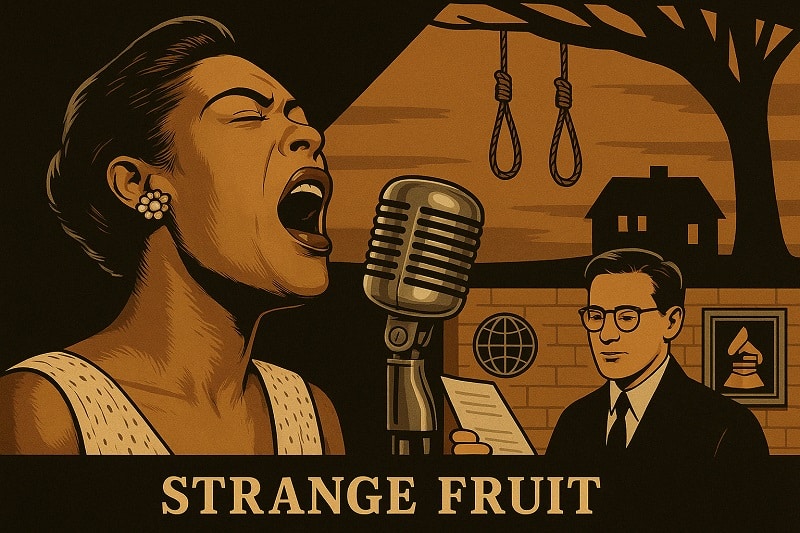

On this day in 1939, Billie Holiday recorded ‘Strange Fruit’

April 20, 1939

Legendary jazz singer Billie Holiday stepped into a Fifth Avenue studio and recorded “Strange Fruit,” a song written by Jewish civil rights activist Abel Meeropol, a high school English teacher upset about the lynchings of Black Americans — more than 6,400 between 1865 and 1950.

Meeropol and his wife had adopted the sons of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were orphaned after their parents’ executions for espionage.

Holiday was drawn to the song, which reminded her of her father, who died when a hospital refused to treat him because he was Black. Weeks earlier, she had sung it for the first time at the Café Society in New York City. When she finished, she didn’t hear a sound.

“Then a lone person began to clap nervously,” she wrote in her memoir. “Then suddenly everybody was clapping.”

The song sold more than a million copies, and jazz writer Leonard Feather called it “the first significant protest in words and music, the first unmuted cry against racism.”

After her 1959 death, both she and the song went into the Grammy Hall of Fame, Time magazine called “Strange Fruit” the song of the century, and the British music publication Q included it among “10 songs that actually changed the world.”

David Margolick traces the tune’s journey through history in his book, “Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday and the Biography of a Song.” Andra Day won a Golden Globe for her portrayal of Holiday in the film, “The United States vs. Billie Holiday.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Mississippians are asked to vote more often than people in most other states

Not long after many Mississippi families celebrate Easter, they will be returning to the polls to vote in municipal party runoff elections.

The party runoff is April 22.

A year does not pass when there is not a significant election in the state. Mississippians have the opportunity to go to the polls more than voters in most — if not all — states.

In Mississippi, do not worry if your candidate loses because odds are it will not be long before you get to pick another candidate and vote in another election.

Mississippians go to the polls so much because it is one of only five states nationwide where the elections for governor and other statewide and local offices are held in odd years. In Mississippi, Kentucky and Louisiana, the election for governor and other statewide posts are held the year after the federal midterm elections. For those who might be confused by all the election lingo, the federal midterms are the elections held two years after the presidential election. All 435 members of the U.S. House and one-third of the membership of the U.S. Senate are up for election during every midterm. In Mississippi, there also are important judicial elections that coincide with the federal midterms.

Then the following year after the midterms, Mississippians are asked to go back to the polls to elect a governor, the seven other statewide offices and various other local and district posts.

Two states — Virginia and New Jersey — are electing governors and other state and local officials this year, the year after the presidential election.

The elections in New Jersey and Virginia are normally viewed as a bellwether of how the incumbent president is doing since they are the first statewide elections after the presidential election that was held the previous year. The elections in Virginia and New Jersey, for example, were viewed as a bad omen in 2021 for then-President Joe Biden and the Democrats since the Republican in the swing state of Virginia won the Governor’s Mansion and the Democrats won a closer-than-expected election for governor in the blue state of New Jersey.

With the exception of Mississippi, Louisiana, Kentucky, Virginia and New Jersey, all other states elect most of their state officials such as governor, legislators and local officials during even years — either to coincide with the federal midterms or the presidential elections.

And in Mississippi, to ensure that the democratic process is never too far out of sight and mind, most of the state’s roughly 300 municipalities hold elections in the other odd year of the four-year election cycle — this year.

The municipal election impacts many though not all Mississippians. Country dwellers will have no reason to go to the polls this year except for a few special elections. But in most Mississippi municipalities, the offices for mayor and city council/board of aldermen are up for election this year.

Jackson, the state’s largest and capital city, has perhaps the most high profile runoff election in which state Sen. John Horhn is challenging incumbent Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba in the Democratic primary.

Mississippi has been electing its governors in odd years for a long time. The 1890 Mississippi Constitution set the election for governor for 1895 and “every four years thereafter.”

There is an argument that the constant elections in Mississippi wears out voters, creating apathy resulting in lower voter turnout compared to some other states.

Turnout in presidential elections is normally lower in Mississippi than the nation as a whole. In 2024, despite the strong support for Republican Donald Trump in the state, 57.5% of registered voters went to the polls in Mississippi compared to the national average of 64%, according to the United States Elections Project.

In addition, Mississippi Today political reporter Taylor Vance theorizes that the odd year elections for state and local officials prolonged the political control for Mississippi Democrats. By 1948, Mississippians had started to vote for a candidate other than the Democrat for president. Mississippians began to vote for other candidates — first third party candidates and then Republicans — because of the national Democratic Party’s support of civil rights.

But because state elections were in odd years, it was easier for Mississippi Democrats to distance themselves from the national Democrats who were not on the ballot and win in state and local races.

In the modern Mississippi political environment, though, Republicans win most years — odd or even, state or federal elections. But Democrats will fare better this year in municipal elections than they do in most other contests in Mississippi, where the elections come fast and often.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mississippi Today

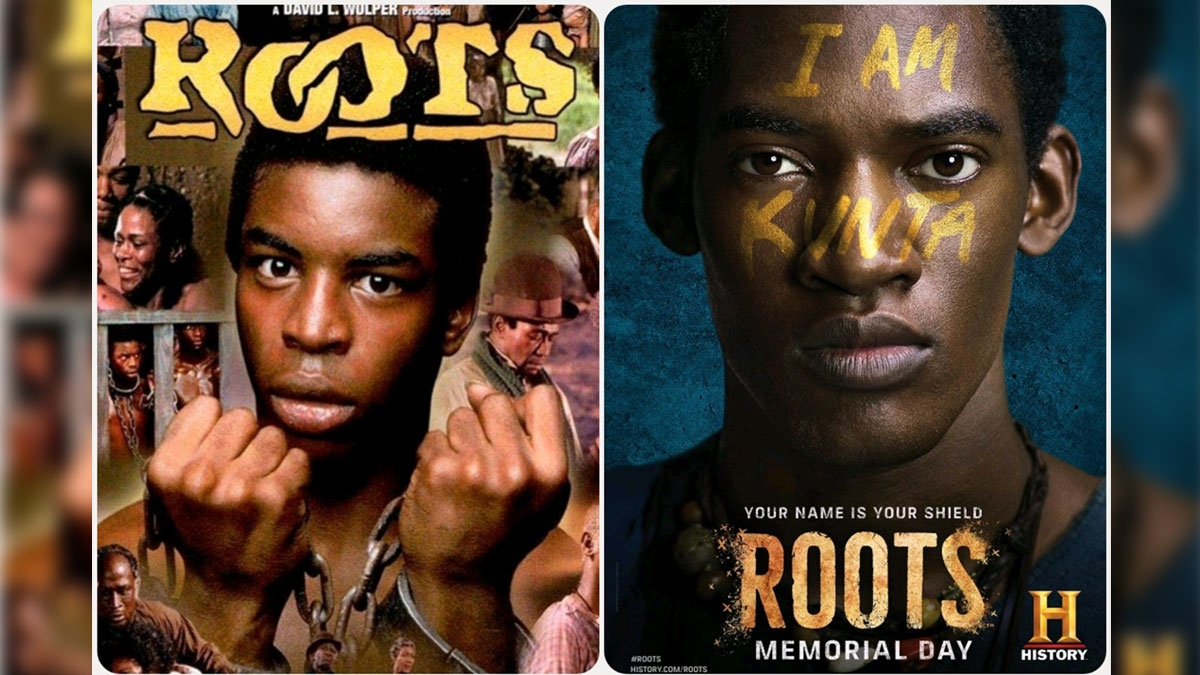

On this day in 1977, Alex Haley awarded Pulitzer for ‘Roots’

April 19, 1977

Alex Haley was awarded a special Pulitzer Prize for “Roots,” which was also adapted for television.

Network executives worried that the depiction of the brutality of the slave experience might scare away viewers. Instead, 130 million Americans watched the epic miniseries, which meant that 85% of U.S. households watched the program.

The miniseries received 36 Emmy nominations and won nine. In 2016, the History Channel, Lifetime and A&E remade the miniseries, which won critical acclaim and received eight Emmy nominations.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoFoley man wins Race to the Finish as Kyle Larson gets first win of 2025 Xfinity Series at Bristol

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoFederal appeals court upholds ruling against Alabama panhandling laws

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days agoFDA warns about fake Ozempic, how to spot it

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed4 days agoLieutenant governor race heats up with early fundraising surge | Virginia

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days agoTwo dead, 9 injured after shooting at Conway park | What we know

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed3 days agoDrivers brace for upcoming I-70 construction, slowdowns

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days agoAbandoned property causing issues in Pine Lawn, neighbor demands action

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed4 days agoThursday April 17, 2025 TIMELINE: Severe storms Friday