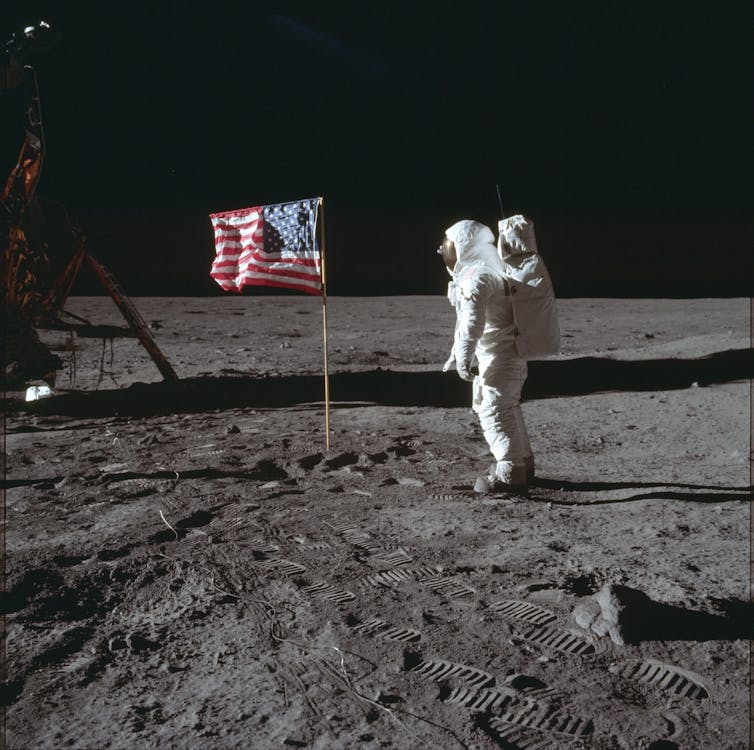

Neil A. Armstrong/NASA via AP

Wayne N White Jr, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University

Private citizens and companies may one day begin to permanently settle outer space and celestial bodies. But if we don’t enact governing laws in the meantime, space settlers may face legal chaos.

Many wars on Earth start over territorial disputes. In order to avoid such disputes in outer space, nations should consider enacting national laws that specify the extent of each settler’s authority in outer space and provide a process to resolve conflicts.

I have been researching and writing about space law for over 40 years. Through my work, I’ve studied ways to avoid war and resolve disputes in space.

Property in space

Space is an international area, and companies and individuals are free to land their space objects – including satellites, human-crewed and robotic spacecraft and human-inhabited facilities – on celestial bodies and conduct operations anywhere they please. This includes both outer space and celestial bodies such as the Moon.

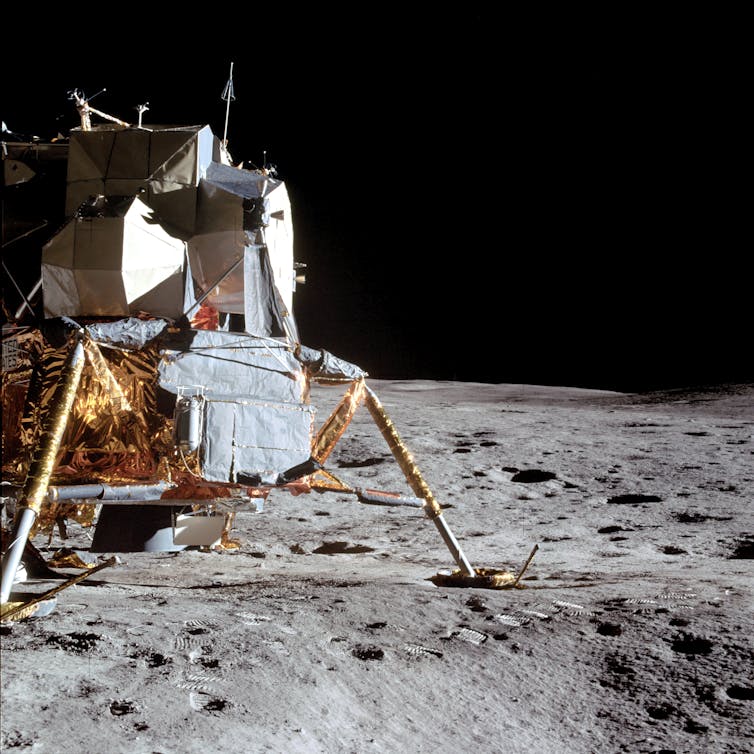

Stocktrek Images/Stocktrek Images via Getty Images

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty prohibits territorial claims in outer space and on celestial bodies in order to avoid disputes. But without national laws governing space settlers, a nation might attempt to protect its citizens’ and companies’ interests by withdrawing from the treaty. They could then claim the territory where its citizens have placed their space objects.

Nations enforce territorial claims through military force, which would likely cost money and lives. An alternative to territorial claims, which I’ve been investigating and have come to prefer, would be to enact real property rights that are consistent with the Outer Space Treaty.

Territorial claims can be asserted only by national governments, while property rights apply to private citizens, companies and national governments that own property. A property rights law could specify how much authority settlers have and protect their investments in outer space and on celestial bodies.

The Outer Space Treaty

In 1967, the Outer Space Treaty went into effect. As of January 2025, 115 countries are party to this treaty, including the United States and most nations that have a space program.

The Outer Space Treaty outlines principles for the peaceful exploration and use of outer space and celestial bodies. However, the treaty does not specify how it will apply to the citizens and companies of nations that are parties to the treaty.

For this reason, the Outer Space Treaty is largely not a self-executing treaty. This means U.S. courts cannot apply the terms of the treaty to individual citizens and companies. For that to happen, the United States would need to enact national legislation that explains how the terms of the treaty apply to nongovernmental entities.

One article of the Outer Space Treaty says that participating countries should make sure that all of their citizens’ space activities comply with the treaty’s terms. Another article then gives these nations the authority to enact laws governing their citizens’ and companies’ private space activities.

This is particularly relevant to the U.S., where commercial activity in space is rapidly increasing.

UN Charter

It is important to note that the Outer Space Treaty requires participating nations to comply with international law and the United Nations Charter.

In the U.N. Charter, there are two international law concepts that are relevant to property rights. One is a country’s right to defend itself, and the other is the noninterference principle.

The international law principle of noninterference gives nations the right to exclude others from their space objects and the areas where they have ongoing activity.

But how will nations apply this concept to their private citizens and companies? Do individual people and companies have the right to exclude others in order to prevent interference with their activities? What can they do if a foreign person interferes or causes damage?

The noninterference principle in the U.N. Charter governs relations between nations, not individuals. Consequently, U.S. courts likely wouldn’t enforce the noninterference principle in a case involving two private parties.

So, U.S. citizens and companies do not have the right to exclude others from their space objects and areas of ongoing activity unless the U.S. enacts legislation giving them that right.

US laws and regulations

The United States has recognized the need for more specific laws to govern private space activities. It has sought international support for this effort through the nonbinding Artemis Accords.

Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images

As of January 2025, 50 nations have signed the Artemis Accords.

The accords explain how important components of the Outer Space Treaty will apply to private space activities. One section of the accords allows for safety zones, where public and private personnel, equipment and operations are protected from harmful interference by other people. The rights to self-defense and noninterference from the U.N. Charter provide a legal basis for safety zones.

Aside from satellite and rocket-launch regulations, the United States has enacted only a few laws – including the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015 – to govern private activities in outer space and on celestial bodies.

As part of this act, any U.S. citizen collecting mineral resources in outer space or on celestial bodies has a right to own, transport, use and sell those resources. This act is an example of national legislation that clarifies how the Outer Space Treaty applies to U.S. citizens and companies.

Property rights

Enacting property rights for outer space would make it clear what rights and obligations property owners have and the extent of their authority over their property.

All nations on Earth have a form of property rights in their legal systems. Property rights typically include the rights to possess, control, develop, exclude, enjoy, sell, lease and mortgage properties. Enacting real property rights in space would create a marketplace for buying, selling, renting and mortgaging property.

Because the Outer Space Treaty prohibits territorial claims, space property rights would not necessarily be “land grabs.” Property rights would operate a little differently in space than on Earth.

Property rights in space would have to be based on the authority that the Outer Space Treaty gives to nations. This authority allows them to govern their citizens and their assets by enacting laws and enforcing them in their courts.

Space property rights would include safety zones around property to prevent interference. So, people would have to get the property owner’s permission before entering a safety zone.

If a U.S. property owner were to sell a space property to a foreign citizen or company, the space objects on the property would have to stay on the property or be replaced with the purchaser’s space objects. That would ensure that the owner’s country still has authority over the property.

Also, if someone transferred their space objects to a foreign citizen or company, the buyer would have to change their objects’ international registration, which would give the buyer’s nation authority over the space objects and the surrounding property.

Nations could likely avoid some territorial disputes if they enact real property laws in space that clearly describe how national authority over property changes when it is sold. Enacting property rights could reduce the legal risks for commercial space companies and support the permanent settlement of outer space and celestial bodies.

U.S. property rights law could also contain a reciprocity provision, which would encourage other nations to pass similar laws and allow participating countries to mutually recognize each other’s property rights.

With a reciprocity provision, property rights could support economic development as commercial companies around the world begin to look to outer space as the next big area of economic growth.![]()

Wayne N White Jr, Adjunct Professor of Aviation and Space Law, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.