Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

Jennifer Selin, Arizona State University

As President Donald Trump issued a slew of executive orders and directives on his first day of his second administration, he explained his actions by saying, “It’s all about common sense.”

For over a century, presidents have pursued initiatives to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of government, couching those efforts in language similar to Trump’s.

Many of these, like Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency, which he appointed billionaire Elon Musk to run, have been designed to capitalize on the expertise of people outside of government. The idea often cited as inspiration for these efforts: The private sector knows how to be efficient and nimble and strives for excellence; government doesn’t.

But government, and government service, is about providing something that the private sector can’t. And outsiders often don’t think about the accountability requirements that the laws and Constitution of the United States impose on government workers and agencies.

Congress, though, can help address these problems and check inappropriate proposals. It can also stand in the way of reform.

Harris & Ewing, photographer, Library of Congress

Proposing reform is nothing new

Perhaps the most famous group to work with a president on improving government was President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Committee on Administrative Management, established in 1936.

That group, commonly referred to as the Brownlow Committee, noted that while critics predicted Roosevelt would bring “decay, destruction, and death of democracy,” the executive branch – and the president who sat atop it – was one of the “very greatest” contributions to modern democracy.

The committee argued that the president was unable to do his job because the executive branch was badly organized, federal employees lacked skills and character, and the budget process needed reform. So it proposed a series of changes designed to increase presidential power over government to enhance performance. Congress went along with some of these proposals, giving the president more staff and authority to reorganize the executive branch.

Since then, almost every president has put together similar recommendations. For example, Presidents Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed former President Herbert Hoover to lead advisory commissions designed to recommend changes to the federal government. President Jimmy Carter launched a series of government improvement projects, and President George W. Bush even created scorecards to rank agencies according to their performance.

In his first term, Trump issued a mandate for reform to reorganize government for the 21st century.

This time around, Trump has taken executive actions to freeze government hiring, create a new entity to promote government efficiency, and give him the ability to fire high-ranking administrators who influence policy.

Most presidential proposals generally fail to come to fruition. But they often spark conversations in Congress and the media about executive power, the effectiveness of federal programs, and what government can do better.

Most presidents have tried the same thing

Historically, most presidents and their advisers – and indeed most scholars – have agreed that government bureaucracy is not designed in ways that promote efficiency. But that is intentional: Stanford political scientist Terry Moe has written that “American public bureaucracy is not designed to be effective. The bureaucracy arises out of politics, and its design reflects the interests, strategies, and compromises of those who exercise political power.”

A common presidential response to this practical reality is to propose government changes that make it look more like the private sector. In 1982, President Ronald Reagan brought together 161 corporate executives overseen by industrialist J. Peter Grace to make recommendations to eliminate government waste and inefficiency, based on their experiences leading successful corporations.

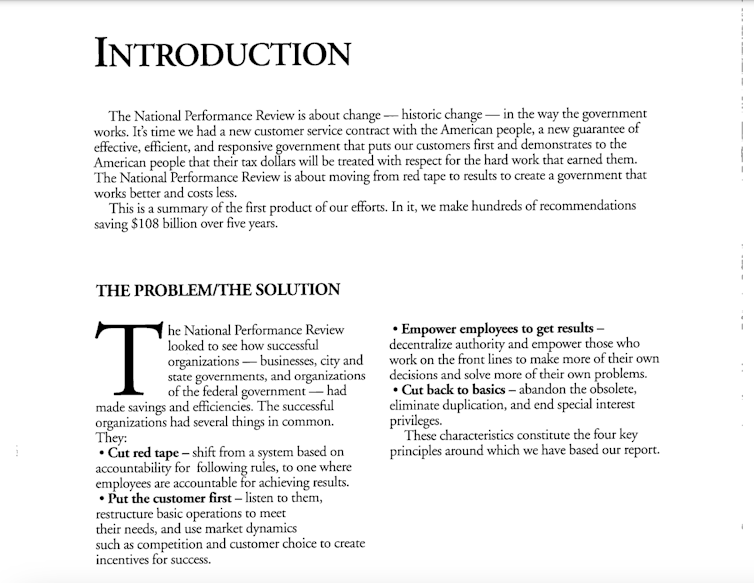

In 1993, President Bill Clinton authorized Vice President Al Gore to launch an effort to reinvent the federal government into one that worked better and cost less.

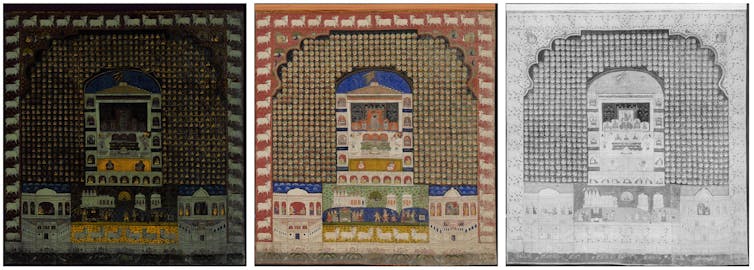

The Clinton administration created teams in every major federal agency, modeled after the private sector’s efficiency standards, to move government “From Red Tape to Results,” as the title of the administration’s plan said.

CIA.gov

Presidential attempts to make government look and work more like people think the private sector works often include adjustments to the terms of federal employment to reward employees who excel at their jobs.

In 1905, for example, President Theodore Roosevelt established a Committee on Department Methods to examine how the federal government could recruit and retain highly qualified employees. One hundred years later, federal agencies still experienced challenges](https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-03-2.pdf) related to hiring and retaining people who could effectively achieve agency missions.

Paul J. Richards/AFP via Getty Images

So why haven’t these plans worked?

At least the past five presidents have faced problems in making long-term changes to government.

In part, this is because government reorganizations and operational reforms like those contemplated by Trump require Congress to make adjustments to the laws of the United States, or at least give the president and federal agencies the money required to invest in changes.

Consider, for example, presidential proposals to invest in new technologies, which are a large part of Trump and Musk’s plans to improve government efficiency. Since at least 1910, when President William Howard Taft established a Commission on Economy and Efficiency to address the “unnecessarily complicated and expensive” way the federal government handled and distributed government documents, presidents have recommended centralizing authority to mandate federal agencies’ use of new technologies to make government more efficient.

But transforming government through technology requires money, people and time. Presidential plans for government-wide change are contingent upon the degree to which federal agencies can successfully implement them.

To sidestep these problems, some presidents have proposed that the government work with the private sector. For example, Trump announced a joint venture with technology companies to invest in the government’s artificial intelligence infrastructure.

Yet as I have found in my previous research, government investment in new technology first requires an assessment of agencies’ current technological skills and the impact technology will have on agency functions, including those related to governmental transparency, accountability and constitutional due process. It’s not enough to go out and buy software that tech giants recommend agencies acquire.

The things that government agencies do, such as regulating the economy, promoting national security and protecting the environment, are incredibly complicated. It’s often hard to see their impact right away.

Recognizing this, Congress has designed a complex set of laws to prevent political interference with federal employees, who tend to look at problems long term. For example, as I have found in my work with Paul Verkuil, former chairman of the Administrative Conference of the United States, Congress intentionally writes laws that require certain government positions to be held by experts who can work in their jobs without worrying about politics.

Congress also writes the laws the federal employees administer, oversees federal programs and decides how much money to appropriate to those programs each year.

So by design, anything labeled a “presidential commission on modernizing/fixing/refocusing government” tells only part of the story and sets out an impossible task. The president can’t make it happen alone. Nor can Elon Musk.

Jennifer Selin, Associate Professor of Law, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.