Priyanka Naik, CC BY-ND

Priyanka Naik, Purdue University

Each cell in your body relies on precise communication with other cells to function properly. At the center of this process are the molecular switches that turn communication signals in the body on and off. These molecules are key players in health and disease. One such molecular switch is G protein-coupled receptor kinases, or GRKs for short.

From vision to heart function and cell growth, GRKs play a vital role in maintaining physiological balance. When they go awry, they can contribute to cardiovascular disease, inflammatory illnesses like rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis, neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, and multiple types of cancer.

Their involvement in a broad range of diseases makes GRKs an attractive drug target. Around 30% to 40% of all drugs currently on the market focus on these proteins. However, designing drugs that selectively target specific GRKs is a difficult task. Because they are structurally similar to each other and to other proteins, molecules binding to one GRK might also bind to many other enzymes and cause unwanted side effects.

A better understanding of how GRKs interact with their targets can help researchers develop better drugs. So my work in the Tesmer Lab at Purdue University focuses on uncovering more information on the structure of GRKs.

What do G protein-coupled receptor kinases look like?

What researchers know about the structure of GRKs has advanced significantly over the past two decades, revealing the intricate mechanisms by which they function.

The ability to physically look at proteins is highly useful for drug development. Seeing a protein’s structure is like looking at a jigsaw puzzle – you can find the missing piece by knowing its shape. Similarly, knowing a protein’s shape helps scientists design molecules that fit perfectly into it, making drugs more effective.

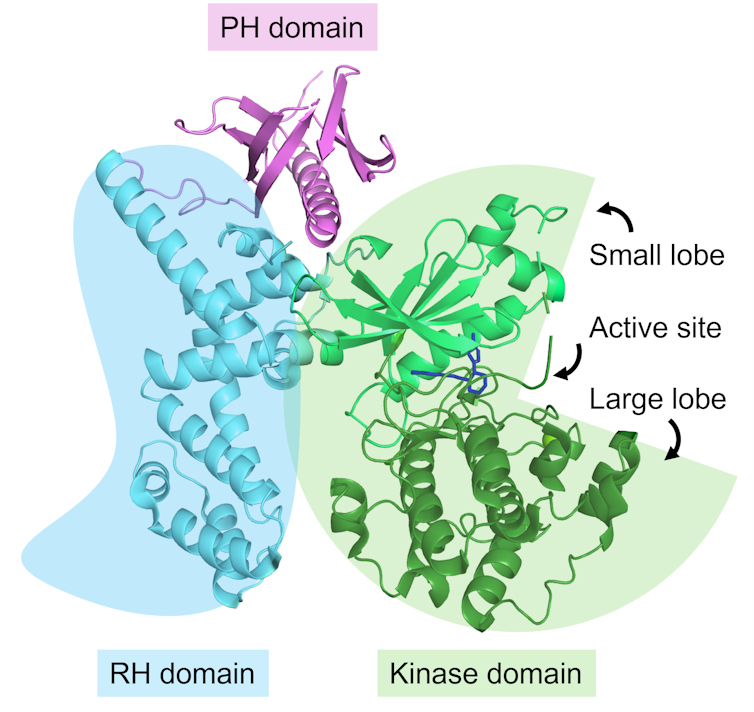

GRKs consist of several modules, or domains, that serve a particular purpose. Together, these modules assemble into a structure resembling a Pac-Man with a ponytail.

The kinase domain – the Pac-Man – is the catalytic center where the protein does its main job: adding a phosphate group to its target to control its activity. It has two subdomains – one small and one large lobe – connected by a hinge that can open and close. Like Pac-Man, this domain closes around reactants and reopens to release products.

Priyanka Naik, CC BY-ND

The RH domain – the ponytail – stabilizes the kinase domain. It guides and docks the GRK to its target protein.

Humans have seven GRKs, each specialized for different tissues and functions, and each unique in structure. Some regulate vision, while others affect your brain, kidney and immune functions, among others. Their structural differences dictate how they interact with their targets, and understanding these distinctions is key to designing drugs that can selectively target each one.

In 2003, researchers in the lab where I work uncovered the first known structure of a GRK – specifically, GRK2, which is involved in heart functions and cell proliferation – by using a technique called macromolecular crystallography. This involved bombarding a GRK2 sample with X-rays and tracing where they bounce off to determine where each atom of the protein is located.

Current state of GRK research

By determining how the three modules of GRK2 are arranged and where its target molecules would bind, my colleagues and I can design drugs that strongly interact with GRK2.

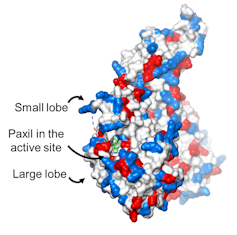

Priyanka Naik, CC BY-ND

For example, in 2012, one of my colleagues discovered that the antidepressant Paxil could inhibit GRK2. To build on this discovery, our team designed drugs with similar shapes to Paxil to identify ones that effectively and selectively inhibit GRK2. The goal was to develop treatments that could target GRK2-related diseases such as heart failure and breast cancer without interfering with other proteins, thereby minimizing side effects.

After determining what Paxil looks like when bound to GRK2, we designed a series of derivative compounds that better fit into GRK2’s active site – the missing jigsaw puzzle pieces. Some of these compounds were able to better block GRK2 compared with Paxil, improving the ability of heart muscle cells to contract. While the research is still in its early stages, our findings suggest that these compounds could potentially be used to treat heart failure.

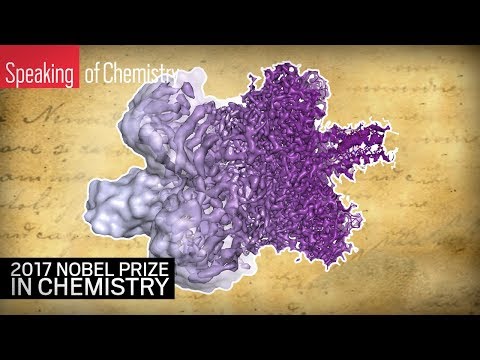

An important missing piece of the story is what GRK2 looks like when bound to its primary target in the cells. These protein complexes are highly shape-shifting, making traditional imaging methods very difficult.

However, recent advances in imaging have made it possible to determine the structure of these molecules. Cryogenic electron microscopy, or cryo-EM, flash-freezes proteins and bombards them with electrons to capture their structure. These studies have thus far revealed what GRK1 and GRK2 look like when bound to two different target proteins, offering critical insights into how they work.

My work focuses on uncovering how GRK2 function is different from GRK1. These proteins play different physiological roles – GRK1 primarily regulates vision, while GRK2 is involved in heart function and cell proliferation. Identifying structural differences in different GRKs will help researchers design drugs that only target the GRK of interest, thus preventing side effects.

By combining cutting-edge imaging techniques with decades of research, scientists in my lab and others hope to one day unlock the full therapeutic potential of GRKs, offering pinpointed treatments for a wide range of diseases.![]()

Priyanka Naik, Ph.D. Candidate in Structural Biology, Purdue University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.