Mississippi Today

Outside doctor told an inmate he needed to see a specialist, but MDOC medical provider has yet to get him to one

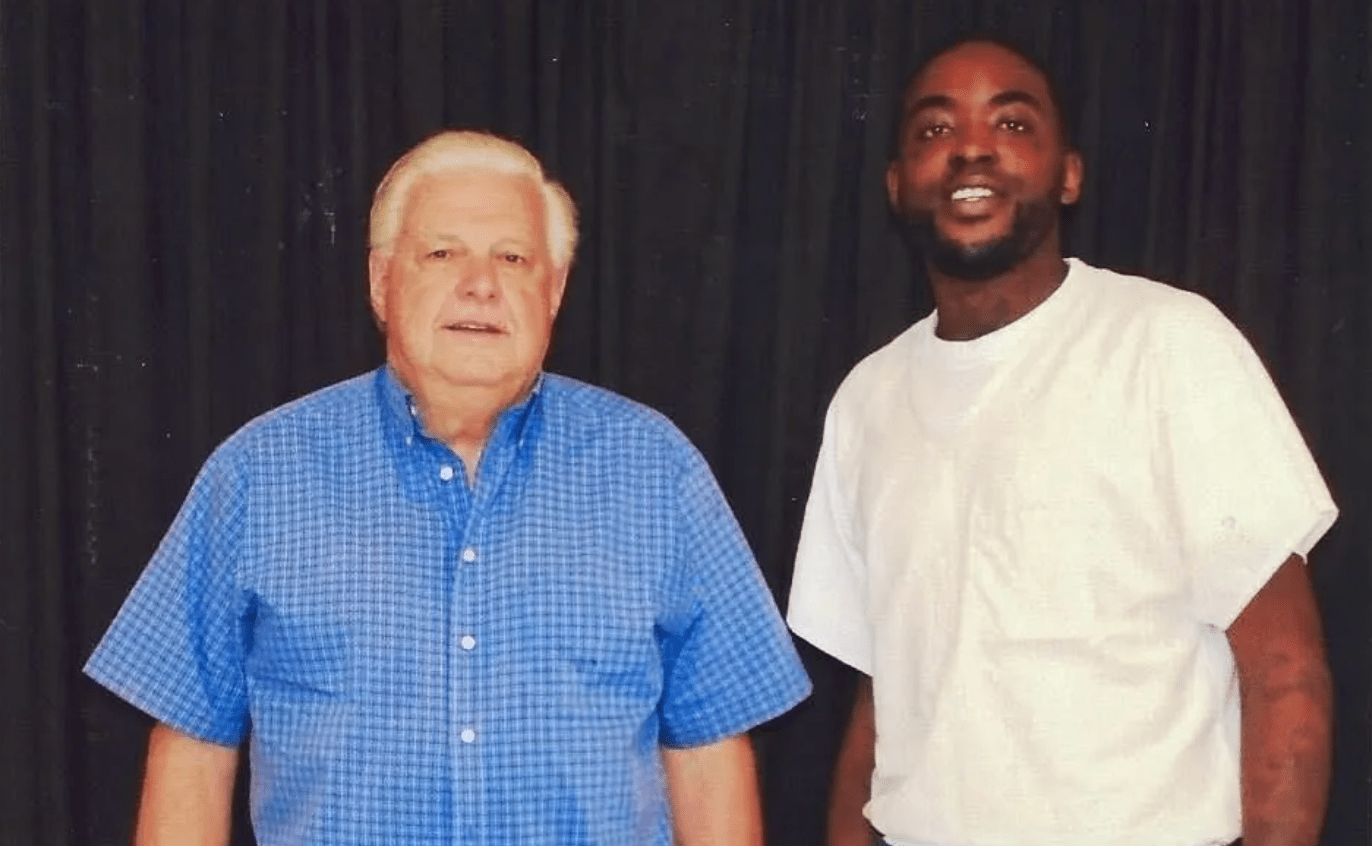

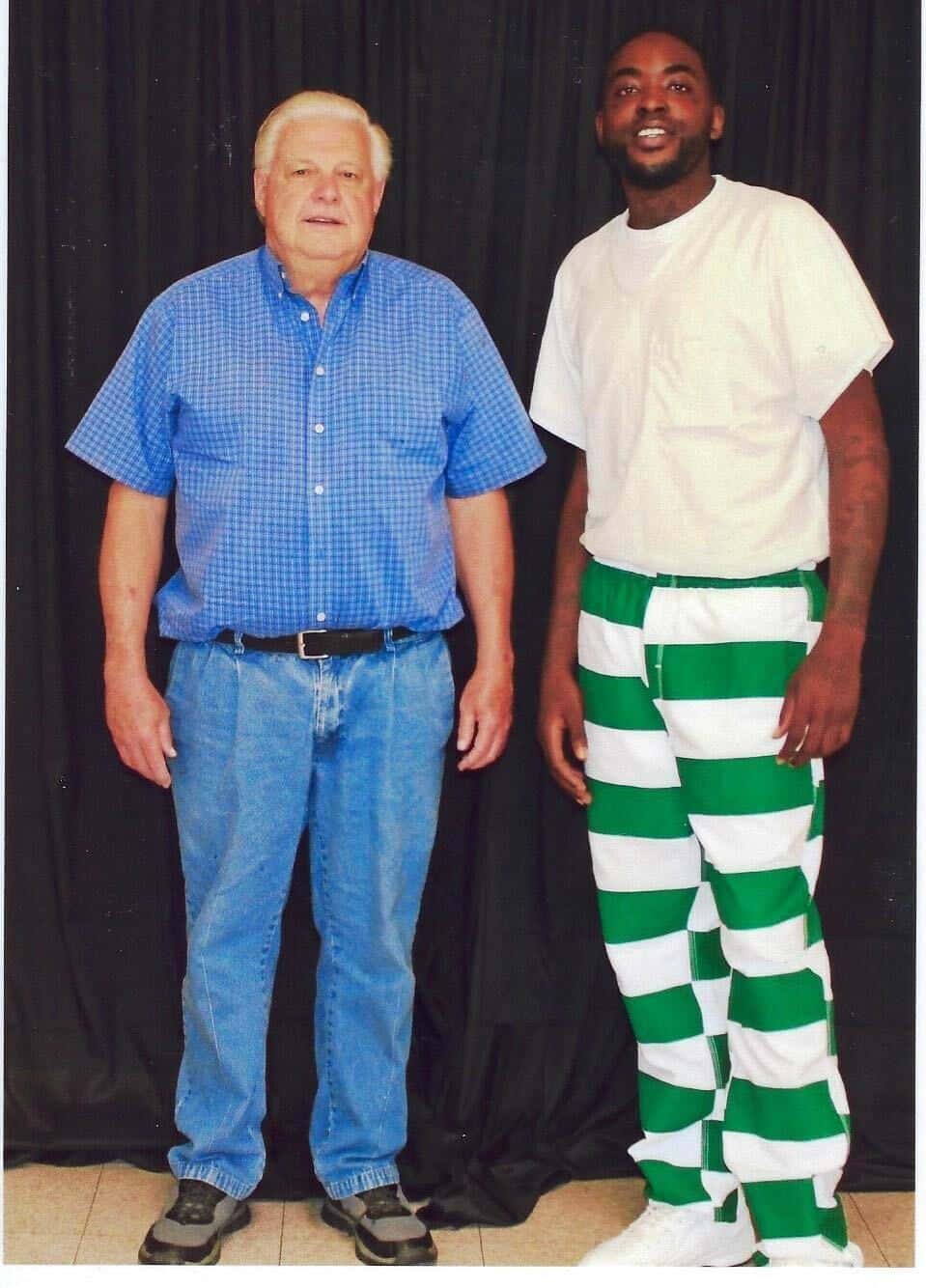

Last month, Charles Young told a prison guard he needed medical attention not long after he first saw bright blood in his urine.

It was a day before a nurse treated him, took a urine sample and concluded that he had a urinary tract infection. Young said she gave him two shots for the pain and antibiotics and sent him back to his cell at the South Mississippi Correctional Institute in Leakesville with some antibiotic pills, which tend to clear up symptoms within a few days.

But as the week went by, he felt pain in his abdomen and lower back and could barely eat or drink. Six days later, he was taken to the nearby Greene County Hospital, where Young said a doctor in the emergency department told him he needed to be seen by a specialist and that his condition was serious.

It’s been more than three weeks since that hospital visit. The first time he saw a doctor at the prison was Oct. 3 – after Mississippi Today and an advocacy group began reaching out to the prison and Mississippi Department of Corrections asking questions about his lack of care. He said he underwent a procedure where a catheter was inserted, but he has not been given the results or any updates since.

Officials told him after the hospital visit an appointment with a urologist has been made, but Young said the doctor he saw last week told him it was unlikely he would see the specialist because of “transportation issues.”

“I don’t know what’s wrong with me,” Young said by phone last week.

While the blood in his urine has subsided, he still has terrible stomach pain, little to no appetite and irregular bowel movements, he said.

Federal health privacy laws prevent the Department of Corrections from commenting directly on Young’s medical case. But more broadly, VitalCore Health Strategies, the state’s contracted medical provider since 2020, provides care to more than 19,000 people in the prison system.

“VitalCore provides primary care services on site,” Mississippi Medical Director Dr. Raman Singh said in a statement. “When a patient needs a higher level of care, VitalCore medical staff take those patients to the specialty clinics and hospitals in the area.”

“With these arrangements, we ensure that our patients have the same level of access to specialist care as other Mississippians.”

An ongoing lawsuit filed by Disability Rights Mississippi in 2021 suggests otherwise. The advocacy group filed the federal lawsuit against VitalCore, the department and Commissioner Burl Cain on behalf of 31 incarcerated men and women across the state’s prisons, including South Mississippi Correctional.

The lawsuit alleges the defendants don’t provide treatment, medication and medical equipment for those in custody. Incarcerated people experienced worsened health conditions or death from ignored or refused calls for treatment and delayed outside appointments and follow up exams, the complaint says.

The lawsuit highlighted dozens of situations, including a delayed diagnosis that led to the death of a woman at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Pearl. Similar to Young, she made several sick calls about her symptoms, including blood in her urine, and complained of shortness of breath and passed out the week she died, according to the lawsuit.

A MDOC spokesperson declined to comment because the lawsuit is ongoing. In court records, the department and VitalCore denied most of the allegations.

Disability Rights Mississippi has gotten involved on behalf of Young, though Communications Director Jane Walton said she can’t comment on his situation specifically.

Walton said because of the nonprofit’s status as a protection advocacy agency, it has unique access to places many people don’t, including prisons. When the group began looking into how disabled people were being treated in Mississippi prisons, it found “egregious” violations and instances where incarcerated people – both with and without disabilities – went without basic medical, mental health and hygiene care.

The lawsuit is in the “class certification” stage, where attorneys must demonstrate certain facts to obtain class action status. These include demonstrating that the plaintiffs have been harmed in similar ways and the class is appropriately defined.

This phase of the lawsuit will likely continue into 2024, Walton said.

Sick calls were often ignored due to lack of staff, the lawsuit alleges. The first time Young needed to see a medical professional about his condition, he was told to come back the next day because there was not one available.

Three doctors, three nurse practitioners, 18 registered nurses and 12 licensed nurse practitioners who exclusively cover South Mississippi Correctional, according to VitalCore and MDOC.

In the two years since the lawsuit has been active, two of the plaintiffs have died, according to court records.

Although Young is no longer seeing blood in his urine, he knows he isn’t entirely better. The pain, weakness and shaking he is still feeling can be connected to an infection in the kidney and bladder.

The 30-year-old said he’s never had a health condition like the one he’s experiencing. He said cancer doesn’t run in his family, but there is no way to rule out the disease until he gets further treatment. Continued blood in the urine and pain can be symptoms of kidney or bladder cancer.

Young said the visit to the outside hospital felt like a ray of hope.

“It felt great to actually know there was a deeper issue wrong with me, and they were trying to get me to proper medical care,” he said.

Greg Havard, CEO of the George Regional Health System, could not comment on Young’s medical case, but said the hospital doesn’t see many patients from the Leakesville prison.

Greene County Regional is able to treat urinary tract infections and bladder conditions, including by using a CT scan and running lab work to make a diagnosis, he said. For more specialized treatment, the hospital refers patients – incarcerated or not – to specialists.

Singh, of VitalCore, said when a patient needs a higher level of care, medical staff take them to specialty clinics and hospitals in the area. For those at South Mississippi Correctional, they would be taken to medical facilities in the Hattiesburg area, which is about 50 miles from the prison. It’s unclear why Young was taken to the small Leakesville hospital.

For more complex conditions, VitalCore sends people to the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson.

Not long after Young started having symptoms, his family began calling the prison to talk with wardens, nurses and other medical staff. Kathy Williams, Young’s aunt, even traveled from Washington to Mississippi to try and help her nephew get medical care.

Officials wouldn’t answer or share information about Young’s condition and treatment with her or other family members due to medical privacy laws, she said. Young said he didn’t know how to provide permission to allow the prison to disclose his health information.

Young has been at South Mississippi Correctional since 2019. He was sentenced to 20 years for manslaughter and aggravated assault and a five-year enhanced penalty of cocaine possession.

Though prison records list a 2033 tentative release date, Young said he has earned time off his sentence to be released in three years. He said he did that by enrolling in educational and skills programs as well as having jobs in the prison.

In his free time, he reads the Bible, prays and preaches, but with his recent health condition, he hasn’t been able to do that as much.

Young’s recent medical and safety concerns have renewed his family’s efforts to get him transferred to a regional facility closer to home. South Mississippi Correctional is hundreds of miles away from Greenville, where Young is from.

Williams said her nephew was told he needed to get medical treatment before being moved because the regional facility likely wouldn’t pay for it. So she, other family members and Young’s

girlfriend are begging for him to be seen by a specialist outside of the prison.

“I just never would have thought the prison system was like this,” said Williams, who is a health care worker.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=294943

Mississippi Today

Jim Hood’s opinion provides a roadmap if lawmakers do the unthinkable and can’t pass a budget

On June 30, 2009, Sam Cameron, the then-executive director of the Mississippi Hospital Association, held a news conference in the Capitol rotunda to publicly take his whipping and accept his defeat.

Cameron urged House Democrats, who had sided with the Hospital Association, to accept the demands of Republican Gov. Haley Barbour to place an additional $90 million tax on the state’s hospitals to help fund Medicaid and prevent the very real possibility of the program and indeed much of state government being shut down when the new budget year began in a few hours. The impasse over Medicaid and the hospital tax had stopped all budget negotiations.

Barbour watched from a floor above as Cameron publicly admitted defeat. Cameron’s decision to swallow his pride was based on a simple equation. He told news reporters, scores of lobbyists and health care advocates who had set up camp in the Capitol as midnight on July 1 approached that, while he believed the tax would hurt Mississippi hospitals, not having a Medicaid budget would be much more harmful.

Just as in 2009, the Legislature ended the 2025 regular session earlier this month without a budget agreement and will have to come back in special session to adopt a budget before the new fiscal year begins on July 1. It is unlikely that the current budget rift between the House and Senate will be as dramatic as the 2009 standoff when it appeared only hours before the July 1 deadline that there would be no budget. But who knows what will result from the current standoff? After all, the current standoff in many ways seems to be more about political egos than policy differences on the budget.

The fight centers around multiple factors, including:

- Whether legislation will be passed to allow sports betting outside of casinos.

- Whether the Senate will agree to a massive projects bill to fund local projects throughout the state.

- Whether leaders will overcome hard feelings between the two chambers caused by the House’s hasty final passage of a Senate tax cut bill filled with typos that altered the intent of the bill without giving the Senate an opportunity to fix the mistakes.

- Whether members would work on a weekend at the end of the session. The Senate wanted to, the House did not.

It is difficult to think any of those issues will rise to the ultimate level of preventing the final passage of a budget when push comes to shove.

But who knows? What we do know is that the impasse in 2009 created a guideline of what could happen if a budget is not passed.

It is likely that parts, though not all, of state government will shut down if the Legislature does the unthinkable and does not pass a budget for the new fiscal year beginning July 1.

An official opinion of the office of Attorney General Jim Hood issued in 2009 said if there is no budget passed by the Legislature, those services mandated in the Mississippi Constitution, such as a public education system, will continue.

According to the Hood opinion, other entities, such as the state’s debt, and court and federal mandates, also would be funded. But it is likely that there will not be funds for Medicaid and many other programs, such as transportation and aspects of public safety that are not specifically listed in the Mississippi Constitution.

The Hood opinion reasoned that the Mississippi Constitution is the ultimate law of the state and must be adhered to even in the absence of legislative action. Other states have reached similar conclusions when their legislatures have failed to act, the AG’s opinion said.

As is often pointed out, the opinion of the attorney general does not carry the weight of law. It serves only as a guideline, though Gov. Tate Reeves has relied on the 2009 opinion even though it was written by the staff of Hood, who was Reeves’ opponent in the contentious 2019 gubernatorial campaign.

But if the unthinkable ever occurs and the Legislature goes too far into a new fiscal year without adopting a budget, it most likely will be the courts — moreso than an AG’s opinion — that ultimately determine if and how state government operates.

In 2009 Sam Cameron did not want to see what would happen if a budget was not adopted. It also is likely that current political leaders do not want to see the results of not having a budget passed before July 1 of this year.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mississippi Today

1964: Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was formed

April 26, 1964

Civil rights activists started the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to challenge the state’s all-white regular delegation to the Democratic National Convention.

The regulars had already adopted this resolution: “We oppose, condemn and deplore the Civil Rights Act of 1964 … We believe in separation of the races in all phases of our society. It is our belief that the separation of the races is necessary for the peace and tranquility of all the people of Mississippi, and the continuing good relationship which has existed over the years.”

In reality, Black Mississippians had been victims of intimidation, harassment and violence for daring to try and vote as well as laws passed to disenfranchise them. As a result, by 1964, only 6% of Black Mississippians were permitted to vote. A year earlier, activists had run a mock election in which thousands of Black Mississippians showed they would vote if given an opportunity.

In August 1964, the Freedom Party decided to challenge the all-white delegation, saying they had been illegally elected in a segregated process and had no intention of supporting President Lyndon B. Johnson in the November election.

The prediction proved true, with white Mississippi Democrats overwhelmingly supporting Republican candidate Barry Goldwater, who opposed the Civil Rights Act. While the activists fell short of replacing the regulars, their courageous stand led to changes in both parties.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Mississippi River flooding Vicksburg, expected to crest on Monday

Warren County Emergency Management Director John Elfer said Friday floodwaters from the Mississippi River, which have reached homes in and around Vicksburg, will likely persist until early May. Elfer estimated there areabout 15 to 20 roads underwater in the area.

“We’re about half a foot (on the river gauge) from a major flood,” he said. “But we don’t think it’s going to be like in 2011, so we can kind of manage this.”

The National Weather projects the river to crest at 49.5 feet on Monday, making it the highest peak at the Vicksburg gauge since 2020. Elfer said some residents in north Vicksburg — including at the Ford Subdivision as well as near Chickasaw Road and Hutson Street — are having to take boats to get home, adding that those who live on the unprotected side of the levee are generally prepared for flooding.

“There are a few (inundated homes), but we’ve mitigated a lot of them,” he said. “Some of the structures have been torn down or raised. There are a few people that still live on the wet side of the levee, but they kind of know what to expect. So we’re not too concerned with that.”

The river first reached flood stage in the city — 43 feet — on April 14. State officials closed Highway 465, which connects the Eagle Lake community just north of Vicksburg to Highway 61, last Friday.

Elfer said the areas impacted are mostly residential and he didn’t believe any businesses have been affected, emphasizing that downtown Vicksburg is still safe for visitors. He said Warren County has worked with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency to secure pumps and barriers.

“Everybody thus far has been very cooperative,” he said. “We continue to tell people stay out of the flood areas, don’t drive around barricades and don’t drive around road close signs. Not only is it illegal, it’s dangerous.”

NWS projects the river to stay at flood stage in Vicksburg until May 6. The river reached its record crest of 57.1 feet in 2011.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoJim talks with Rep. Robert Andrade about his investigation into the Hope Florida Foundation

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoPrayer Vigil Held for Ronald Dumas Jr., Family Continues to Pray for His Return | April 21, 2025 | N

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days ago‘Trainwreck on the horizon’: The costly pains of Mississippi’s small water and sewer systems

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days agoTrump touts manufacturing while undercutting state efforts to help factories

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days agoMeteorologist Chita Craft is tracking a Severe Thunderstorm Warning that's in effect now

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days agoAs country grows more polarized, America needs unity, the ‘Oklahoma Standard,’ Bill Clinton says

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed1 day ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed1 day agoMissouri lawmakers on the cusp of legalizing housing discrimination

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed6 days agoTaking video of military bases using drones could be outlawed | Virginia