Mississippi Today

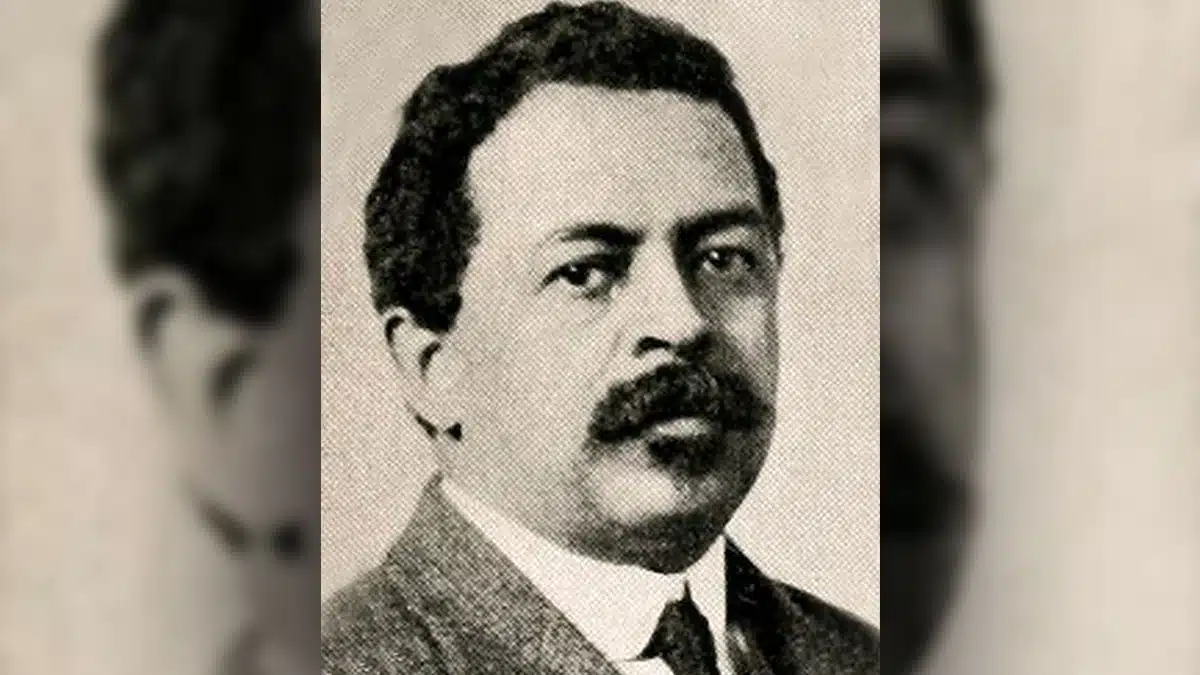

On this day in 1914

Nov. 12, 1914

Civil rights leader William Monroe Trotter led a delegation that confronted President Woodrow Wilson.

Raised in Hyde Park, Massachusetts, Trotter had more education than the president. He had graduate and postgraduate degrees from Harvard University, where he became the first Black member of Phi Beta Kappa.

“New Englanders liked to talk as if ‘the Negro problem’ afflicted only the South,” The New Yorker wrote of him, “but Trotter looked around his beloved Boston and saw segregation in the city’s churches, gyms, and hospitals. This ‘fixed caste of color’ meant that ‘every colored American would be a civic outcast, forever alien in public life,’ he wrote.”

In 1901, he started The Guardian with the motto: “For every right, with all thy might.” The newspaper called itself “an organ which is to voice intelligently the needs and aspirations” of Black Americans.”

Both he and his wife, Deenie, published The Guardian each Saturday, only missing two issues: “The Trotters had no children and did not want any; The Guardian was their child.”

In their pages, Trotter leveled vicious attacks against Booker T. Washington and his accommodation policies, calling him “the Great Traitor.” When Trotter began to question Washington at a gathering of 2,000, a fight broke out, which became known as “the Boston riot,” and he was arrested, spending 30 days in jail. The wealth his family once enjoyed turned to poverty because of the money he sunk into his newspaper.

“It has cost me considerable money, but I could not keep out of it,” he wrote. “I can now feel that I am doing my duty and trying to show the light to those in darkness and keep them from at least being duped into helping in their own enslavement.”

He turned his attention to political candidates he felt would support African Americans and began backing Wilson, whom he met and shook hands with in 1912 “with great cordiality.”

A year later, he and Ida B. Wells and other civil rights leaders expressed dismay over the reinstitution of Jim Crow and even shared a chart that showed which federal offices had begun separating workers by race.

In 1914, Trotter and other Black leaders appeared at the White House with 20,000 signatures, demanding an end to Jim Crow in federal offices. The leaders told Wilson they felt betrayed because they had supported him in the election, and he had since reinstituted segregation in the federal government that included separate toilets and dismissed high-level Black appointees.

“Only two years ago you were heralded as perhaps the second Lincoln,” Trotter said, “and now the Afro-American leaders who supported you are hounded as false leaders and traitors to their race.”

He reminded the president — who had been busy championing his “New Freedom” program to restore fair-labor practices — that he had promised to aid Black Americans in “advancing the interest of their race in the United States. … Have you a ‘New Freedom’ for white Americans and a new slavery for your Afro-American fellow citizens? God forbid!”

Wilson responded that “segregation is not humiliating but a benefit” and that he had put the practice back in place because of friction between Black and white clerks. Trotter challenged this claim, calling Jim Crow humiliating to Black workers.

Wilson stuck to his guns, telling Trotter that if he and other Black Americans think “you are being humiliated, you will believe it.” The exchange lasted 45 minutes, and the president challenged Trotter’s “tone” as offensive: “You have spoiled the whole cause for which you came.”

The civil rights leader responded, “I am pleading for simple justice. If my tone has seemed so contentious, why has my tone been misunderstood?”

The argument landed on the front page of The New York Times. During World War I, the State Department refused to give Trotter a passport to Paris. To get around the restriction, he took a job as a cook on a freighter to France, and when he began reporting on the plight of Black soldiers, French newspapers shared his reporting, and he spoke there about discrimination against African Americans.

When Trotter returned home, he was welcomed by 2,000 supporters. He unsuccessfully championed a section added to Wilson’s 14 Points for peace that would say, “The elimination of civil, political, and judicial distinctions based on race or color in all nations for the new era of freedom everywhere.”

Trotter helped found the Niagara Movement, a forerunner of the NAACP. The civil rights organization adopted his proposal to address segregated transportation as a grievance, but the group rejected his proposal to make lynching a federal crime.

He championed cases the NAACP was slower to pursue, including Jane Bosfield, a Black woman was told she could only work for a Massachusetts hospital if she ate separately from her white fellow workers.

When the racist movie, ‘The Birth of a Nation’, appeared on a screen, the national NAACP tried to raise money for a rival film to counter those lies, but Trotter believed in direct action. His protests succeeded in shutting down a play that was the basis for the movie, which depicted Klansmen as heroes. After failing to halt the debut of the film in Boston, he teamed up with Roman Catholics to get a revival showing canceled.

His tactics were later used by the modern civil rights movement “to integrate lunch counters, buses, schools, and other essential spaces,” The New Yorker wrote. And his mindset “incubated the politics of Malcolm X and of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.”

A multicultural center at the University of Michigan bears Trotter’s name, and his first home in Dorchester is now a National Historic Landmark. He made the list of the 100 Greatest African Americans.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=304949

Mississippi Today

Hospitals see danger in Medicaid spending cuts

Mississippi hospitals could lose up to $1 billion over the next decade under the sweeping, multitrillion-dollar tax and policy bill President Donald Trump signed into law last week, according to leaders at the Mississippi Hospital Association.

The leaders say the cuts could force some already-struggling rural hospitals to reduce services or close their doors.

The law includes the largest reduction in federal health and social safety net programs in history. It passed 218-214, with all Democrats voting against the measure and all but five Republicans voting for it.

In the short term, these cuts will make health care less accessible to poor Mississippians by making the eligibility requirements for Medicaid insurance stiffer, likely increasing people’s medical debt.

In the long run, the cuts could lead to worsening chronic health conditions such as diabetes and obesity for which Mississippi already leads the nation, and making private insurance more expensive for many people, experts say.

“We’ve got about a billion dollars that are potentially hanging in the balance over the next 10 years,” Mississippi Hospital Association President Richard Roberson said Wednesday during a panel discussion at his organization’s headquarters.

“If folks were being honest, the entire system depends on those rural hospitals,” he said.

Mississippi’s uninsured population could increase by 160,000 people as a combined result of the new law and the expiration of Biden-era enhanced subsidies that made marketplace insurance affordable – and which Trump is not expected to renew – according to KFF, a health policy research group.

That could make things even worse for those who are left on the marketplace plans.

“Younger, healthier people are going to leave the risk pool, and that’s going to mean it’s more expensive to insure the patients that remain,” said Lucy Dagneau, senior director of state and local campaigns at the American Cancer Society.

Among the biggest changes facing Medicaid-eligible patients are stiffer eligibility requirements, including proof of work. The new law requires able-bodied adults ages 19 to 64 to work, do community service or attend an educational program at least 80 hours a month to qualify for, or keep, Medicaid coverage and federal food aid.

Opponents say qualified recipients could be stripped of benefits if they lose a job or fail to complete paperwork attesting to their time commitment.

Georgia became the case study for work requirements with a program called Pathways to Coverage, which was touted as a conservative alternative to Medicaid expansion.

Ironically, the 54-year-old mechanic chosen by Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp to be the face of the program got so fed up with the work requirements he went from praising the program on television to saying “I’m done with it” after his benefits were allegedly cancelled twice due to red tape.

Roberson sent several letters to Mississippi’s congressional members in weeks leading up to the final vote on the sweeping federal legislation, sounding the alarm on what it would mean for hospitals and patients.

Among Roberson’s chief concerns is a change in the mechanism called state directed payments, which allows states to beef up Medicaid reimbursement rates – typically the lowest among insurance payors. The new law will reduce those enhanced rates to nearly as low as the Medicare rate, costing the state at least $500 million and putting rural hospitals in a bind, Roberson told Mississippi Today.

That change will happen over 10 years starting in 2028. That, in conjunction with the new law’s one-time payment program called the Rural Health Care Fund, means if the next few years look normal, it doesn’t mean Mississippi is safe, stakeholders warn.

“We’re going to have a sort of deceiving situation in Mississippi where we look a little flush with cash with the rural fund and the state directed payments in 2027 and 2028, and then all of a sudden our state directed payments start going down and that fund ends and then we’re going to start dipping,” said Leah Rupp Smith, vice president for policy and advocacy at the Mississippi Hospital Association.

Even with that buffer time, immediate changes are on the horizon for health care in Mississippi because of fear and uncertainty around ever-changing rules.

“Hospitals can’t budget when we have these one-off programs that start and stop and the rules change – and there’s a cost to administering a program like this,” Smith said.

Since hospitals are major employers – and they also provide a sense of safety for incoming businesses – their closure, especially in rural areas, affects not just patients but local economies and communities.

U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson is the only Democrat in Mississippi’s congressional delegation. He voted against the bill, while the state’s two Republican senators and three Republican House members voted for it. Thompson said in a statement that the new law does not bode well for the Delta, one of the poorest regions in the U.S.

“For my district, this means closed hospitals, nursing homes, families struggling to afford groceries, and educational opportunities deferred,” Thompson said. “Republicans’ priorities are very simple: tax cuts for (the) wealthy and nothing for the people who make this country work.”

While still colloquially referred to as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the name was changed by Democrats invoking a maneuver that has been used by lawmakers in both chambers to oppose a bill on principle.

“Democrats are forcing Republicans to delete their farcical bill name,” Senate Democratic Leader Charles Schumer of New York said in a statement. “Nothing about this bill is beautiful — it’s a betrayal to American families and it’s undeserving of such a stupid name.”

The law is expected to add at least $3.3 trillion to the nation’s debt over the next 10 years, according to the most recent estimate from the Congressional Budget Office.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Hospitals see danger in Medicaid spending cuts appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article reports on the negative impacts of a major federal tax and policy bill on Medicaid funding and rural hospitals in Mississippi. While it presents factual details and statements from stakeholders, the tone and framing emphasize the harmful consequences for vulnerable populations and health care access, aligning with concerns typically raised by center-left perspectives. The article highlights opposition by Democrats and critiques the bill’s priorities, particularly its effect on poor and rural communities, suggesting sympathy toward social safety net preservation. However, it maintains mostly factual reporting without overt partisan language, resulting in a moderate center-left bias.

Crooked Letter Sports Podcast

Podcast: The Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame Class of ’25

The MSHOF will induct eight new members on Aug 2. Rick Cleveland has covered them all and he and son Tyler talk about what makes them all special.

Stream all episodes here.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Podcast: The Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame Class of '25 appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Mississippi Today

‘You’re not going to be able to do that anymore’: Jackson police chief visits food kitchen to discuss new public sleeping, panhandling laws

Diners turned watchful eyes to the stage as Jackson Police Chief Joseph Wade took to the podium. He visited Stewpot Community Services during its daily free lunch hour Thursday to discuss new state laws, which took effect two days earlier, targeting Mississippians experiencing homelessness.

“I understand that you are going through some hard times right now. That’s why I’m here,” Wade said to the crowd. “I felt it was important to come out here and speak with you directly.”

Wade laid out the three bills that passed earlier this year: House Bill 1197, the “Safe Solicitation Act,” HB 1200, the “Real Property Owners Protection Act” and HB 1203, a bill that prohibits camping on public property.

“Sleeping and laying in public places, you’re not going to be able to do that anymore,” he said. “There’s a law that has been passed that you can’t just set up encampments on public or private properties where it’s a public nuisance, it’s a problem.”

The “Real Property Owners Protection Act,” authored by Rep. Brent Powell, R-Brandon, is a bill that expedites the process of removing squatters. The “Safe Solicitation Act,” authored by Rep. Shanda Yates, I-Jackson, requires a permit for panhandling and allows people to be charged with a misdemeanor if they violate this law. The offense is punishable by a fine not to exceed $300 and an offender could face up to six months in jail. Wade said he’s currently working with his legal department to determine the best strategy for creating and issuing permits.

“We’re going to navigate these legal challenges, get some interpretations, not only from our legal department, but the Attorney General’s office to ensure that we are doing it legally and lawfully, because I understand that these are citizens,” he said. “I understand that they deserve to be treated with respect, and I understand that we are going to do this without violating their constitutional rights.”

Wade said the Jackson Police Department is steadily fielding reports of squatters in abandoned properties and the law change gives officers new power to remove them more quickly. The added challenge? Figuring out what to do with a person’s belongings.

“These people are carrying around what they own, but we are not a repository for all of their stuff,” he said. “So, when we make that arrest, we’ve got to have a strategic plan as to what we do with their stuff.”

Wade said there needs to be a deeper conversation around the issues that lead someone to becoming homeless.

“A lot of people that we’re running across that are homeless are also suffering from medical conditions, mental health issues, and they’re also suffering from drug addiction and substance abuse. We’ve got to have a strategic approach, but we also can’t log jam our jail down in Raymond,” Wade said.

He estimates that more than 800 people are currently incarcerated at the Raymond Detention Center, and any increase could strain the system as the laws continue to be enforced.

“I think there’s layers that we have to work through, there’s hurdles that we are going to overcome, but we’ve got to make sure that we do it and make sure that my team and JPD is consistent in how we enforce these laws,” Wade said.

Diners applauded Wade after he spoke, in between bites of fried chicken, salad, corn and 4th of July-themed packaged cakes. Wade offered to answer questions, but no one asked any.

Rev. Jill Buckley, executive director of Stewpot, said that the legislation is a good tool to address issues around homelessness and community needs. She doesn’t want to see people who are homeless be criminalized, but she also wants communities to be safe.

“I support people’s right to self determine, and we can’t impose our choices on other people, but there are some cases in which that impinges on community safety, and so to the extent that anyone who is camping or panhandling or squatting and is a danger to themselves and others, of course, I fully support that kind of law. I don’t support homelessness being criminalized as such,” Buckley said.

Many of the people Wade addressed while they ate Thursday said they have housing, don’t panhandle, and shouldn’t be directly impacted by the legislation. But Marcus Willis, 42, said it would make more sense if elected officials wanted to combat the negative impacts of homelessness that they help more people secure employment.

“There ain’t enough jobs,” said Willis, who was having lunch with his girlfriend Amber Ivy.

The two live in an apartment together nearby on Capitol Street, where Ivy landed after her mother, whom Ivy had been living with, suffered a stroke and lost the property. Similarly, Willis started coming to eat at Stewpot after his grandmother, whose house he used to visit for lunch, passed away.

Willis holds odd jobs – cutting grass, home and auto repair – so the income is inconsistent, and every opportunity for stable employment he said he’s found is outside of Jackson in the suburbs. The couple doesn’t have a car.

Making rent every month usually depends on their ability to find someone to help chip in, said Ivy, who is in recovery from substance abuse. She said she’s watched problems surrounding homelessness grow over the years in Jackson. Ivy grew up near Stewpot and has lived in various neighborhoods across the city – except for the times she moved out of state when things got too rough.

“There was just moments where I just had to leave,” Ivy said. “Sometimes if you hit a slump here, there’s almost no way for you to get out of it.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post 'You're not going to be able to do that anymore': Jackson police chief visits food kitchen to discuss new public sleeping, panhandling laws appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Right

This article primarily reports on new laws in Jackson, Mississippi, targeting public sleeping, panhandling, and squatting, focusing on statements by Police Chief Joseph Wade and community perspectives. The coverage presents the legislative measures—authored by Republican and independent lawmakers—with a tone that emphasizes law enforcement challenges and community safety, reflecting a conservative approach to homelessness as a public order issue. While it includes voices concerned about criminalization and the need for social support, the overall framing centers on law enforcement and property protection. The article maintains factual reporting without overt editorializing but leans slightly toward a center-right perspective by highlighting legal enforcement as a solution.

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

Real-life Uncle Sam's descendants live in Arkansas

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed5 days ago

'Big Beautiful Bill' already felt at Georgia state parks | FOX 5 News

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days ago

LOFT report uncovers what led to multi-million dollar budget shortfall

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

Alabama schools to lose $68 million in federal grants under Trump freeze

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

Celebrate St. Louis returns with new Superman-themed drone show

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days ago

Tropical Depression Three to bring rain, gusty winds to the CSRA this Fourth of July weekend

-

The Center Square4 days ago

Here are the violent criminals Judge Murphy tried to block from deportation | Massachusetts

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days ago

What’s being explored at the ‘Pit of Despair?’ Razor wire OK atop fence within city limits? Mystery pile of dirt along I-26? • Asheville Watchdog