NASA

Dan Kotlyar, Georgia Institute of Technology

NASA plans to send crewed missions to Mars over the next decade – but the 140 million-mile (225 million-kilometer) journey to the red planet could take several months to years round trip.

This relatively long transit time is a result of the use of traditional chemical rocket fuel. An alternative technology to the chemically propelled rockets the agency develops now is called nuclear thermal propulsion, which uses nuclear fission and could one day power a rocket that makes the trip in just half the time.

Nuclear fission involves harvesting the incredible amount of energy released when an atom is split by a neutron. This reaction is known as a fission reaction. Fission technology is well established in power generation and nuclear-powered submarines, and its application to drive or power a rocket could one day give NASA a faster, more powerful alternative to chemically driven rockets.

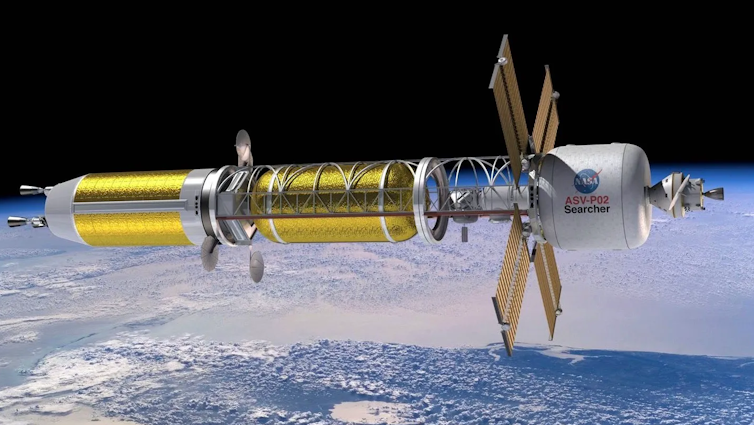

NASA and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency are jointly developing NTP technology. They plan to deploy and demonstrate the capabilities of a prototype system in space in 2027 – potentially making it one of the first of its kind to be built and operated by the U.S.

Nuclear thermal propulsion could also one day power maneuverable space platforms that would protect American satellites in and beyond Earth’s orbit. But the technology is still in development.

I am an associate professor of nuclear engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology whose research group builds models and simulations to improve and optimize designs for nuclear thermal propulsion systems. My hope and passion is to assist in designing the nuclear thermal propulsion engine that will take a crewed mission to Mars.

Nuclear versus chemical propulsion

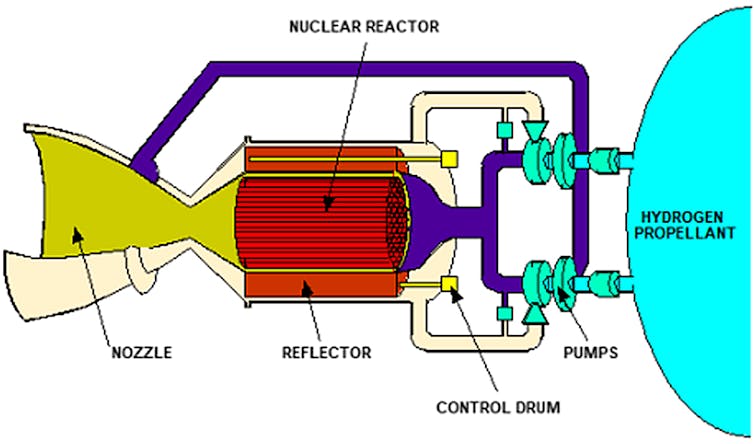

Conventional chemical propulsion systems use a chemical reaction involving a light propellant, such as hydrogen, and an oxidizer. When mixed together, these two ignite, which results in propellant exiting the nozzle very quickly to propel the rocket.

NASA Glenn Research Center

These systems do not require any sort of ignition system, so they’re reliable. But these rockets must carry oxygen with them into space, which can weigh them down. Unlike chemical propulsion systems, nuclear thermal propulsion systems rely on nuclear fission reactions to heat the propellant that is then expelled from the nozzle to create the driving force or thrust.

In many fission reactions, researchers send a neutron toward a lighter isotope of uranium, uranium-235. The uranium absorbs the neutron, creating uranium-236. The uranium-236 then splits into two fragments – the fission products – and the reaction emits some assorted particles.

More than 400 nuclear power reactors in operation around the world currently use nuclear fission technology. The majority of these nuclear power reactors in operation are light water reactors. These fission reactors use water to slow down the neutrons and to absorb and transfer heat. The water can create steam directly in the core or in a steam generator, which drives a turbine to produce electricity.

Nuclear thermal propulsion systems operate in a similar way, but they use a different nuclear fuel that has more uranium-235. They also operate at a much higher temperature, which makes them extremely powerful and compact. Nuclear thermal propulsion systems have about 10 times more power density than a traditional light water reactor.

Nuclear propulsion could have a leg up on chemical propulsion for a few reasons.

Nuclear propulsion would expel propellant from the engine’s nozzle very quickly, generating high thrust. This high thrust allows the rocket to accelerate faster.

These systems also have a high specific impulse. Specific impulse measures how efficiently the propellant is used to generate thrust. Nuclear thermal propulsion systems have roughly twice the specific impulse of chemical rockets, which means they could cut the travel time by a factor of 2.

Nuclear thermal propulsion history

For decades, the U.S. government has funded the development of nuclear thermal propulsion technology. Between 1955 and 1973, programs at NASA, General Electric and Argonne National Laboratories produced and ground-tested 20 nuclear thermal propulsion engines.

But these pre-1973 designs relied on highly enriched uranium fuel. This fuel is no longer used because of its proliferation dangers, or dangers that have to do with the spread of nuclear material and technology.

The Global Threat Reduction Initiative, launched by the Department of Energy and National Nuclear Security Administration, aims to convert many of the research reactors employing highly enriched uranium fuel to high-assay, low-enriched uranium, or HALEU, fuel.

High-assay, low- enriched uranium fuel has less material capable of undergoing a fission reaction, compared with highly enriched uranium fuel. So, the rockets needs to have more HALEU fuel loaded on, which makes the engine heavier. To solve this issue, researchers are looking into special materials that would use fuel more efficiently in these reactors.

NASA and the DARPA’s Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Operations, or DRACO, program intends to use this high-assay, low-enriched uranium fuel in its nuclear thermal propulsion engine. The program plans to launch its rocket in 2027.

As part of the DRACO program, the aerospace company Lockheed Martin has partnered with BWX Technologies to develop the reactor and fuel designs.

The nuclear thermal propulsion engines in development by these groups will need to comply with specific performance and safety standards. They’ll need to have a core that can operate for the duration of the mission and perform the necessary maneuvers for a fast trip to Mars.

Ideally, the engine should be able to produce high specific impulse, while also satisfying the high thrust and low engine mass requirements.

Ongoing research

Before engineers can design an engine that satisfies all these standards, they need to start with models and simulations. These models help researchers, such as those in my group, understand how the engine would handle starting up and shutting down. These are operations that require quick, massive temperature and pressure changes.

The nuclear thermal propulsion engine will differ from all existing fission power systems, so engineers will need to build software tools that work with this new engine.

My group designs and analyzes nuclear thermal propulsion reactors using models. We model these complex reactor systems to see how things such as temperature changes may affect the reactor and the rocket’s safety. But simulating these effects can take a lot of expensive computing power.

We’ve been working to develop new computational tools that model how these reactors act while they’re starting up and operated without using as much computing power.

My colleagues and I hope this research can one day help develop models that could autonomously control the rocket.![]()

Dan Kotlyar, Associate Professor of Nuclear and Radiological Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.