Mississippi Today

National Press Club awards Mississippi Today with its highest press freedom award

Editor’s note: This press release was drafted and released by the National Press Club and is republished with permission.

WASHINGTON, D.C. — The National Press Club is honoring Mississippi Today — a nonprofit, non-partisan newsroom based in Jackson, Mississippi — with its highest honor for press freedom, the John Aubuchon Press Freedom Award.

Mississippi Today is currently involved in a legal case to protect privileged documents used in producing a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation and named in an ensuing defamation case brought by the state’s former governor. The case has wide-ranging implications for press freedom in the United States, including journalist-source protections.

“In a country that holds freedom of the press as one of its core rights, it is shocking that any court — let alone the highest one in a state — would require reporters to hand over their sources simply because the governor was upset to be caught red-handed misusing federal welfare funds,” said Emily Wilkins, president of the National Press Club. “Mississippi Today’s reporting shined light on a critical issue impacting thousands of Americans, and we hope this award both honors their work and draws attention and support for their case.”

Mississippi Today is an authoritative voice on politics and policy in the state of Mississippi and produces essential coverage on education, public health, justice, environment, equity, and more.

The outlet won a 2022 Pulitzer Prize for its investigation into a $77 million welfare scandal that revealed how the state’s former governor, Phil Bryant, used his office to benefit his friends and family.

Bryant then sued Mississippi Today and its CEO Mary Margaret White in July 2023, claiming that the series defamed him. Editor-in-chief Adam Ganucheau and reporter Anna Wolfe were added as defendants in May 2024, according to an editor’s note on the outlet’s website.

On June 6, 2024, Mississippi Today appealed a county judge’s order to turn over privileged documents in relation to the defamation lawsuit. The Mississippi Supreme Court has not yet ruled on the newsroom’s appeal.

“Ours may be a Mississippi case, but the ramifications absolutely could impact every American journalist who has long been granted constitutional protections to dutifully hold powerful leaders to account,” Ganucheau said. “But this fight is not just about protecting journalists and our sources. We’re also fighting to ensure every single American citizen never loses a fuller understanding of how leaders truly operate when their doors are closed and they think no one is watching. As we continue to stand up for press freedom everywhere, it’s truly humbling to be recognized by the National Press Club in this way.”

A team of attorneys is representing Mississippi Today in its case: Henry Laird at Wise Carter; and Ted Boutrous Jr., Lee Crain, Sasha Duddin, and Peter Jacobs at Gibson Dunn. The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press is also providing legal support.

The John Aubuchon Press Freedom Award is named for a former National Press Club president who fervently advocated for press freedom. By selecting Mississippi Today as the domestic honoree, the Club and the Institute are committing to monitor and support this precedent-setting case for the First Amendment protection of reporters’ privilege.

The National Press Club will confer the 2024 Aubuchon awards, along with the Neil and Susan Sheehan Award for Investigative Journalism during its annual Fourth Estate Award Gala honoring Axios’ Jim VandeHei and Mike Allen on Nov. 21 in Washington, D.C.

The gala dinner is a fundraiser for the Club’s nonprofit affiliate, the National Press Club Journalism Institute, which produces training to equip journalists with skills and standards to inform the public in ways that inspire civic engagement. Tickets and more information for the event can be found here.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1956

Feb. 24, 1956

U.S. Sen. Harry F. Byrd Sr. coined the term “Massive Resistance” to unite white leaders in Virginia in their campaign to preserve segregation. The policy appealed to white Virginians’ racial views, their fears and their disdain for federal “intrusion” into the “Southern way of life.”

Virginia passed laws to deny state funds to any integrated school and created tuition grants for students who refused to attend these schools. Other states copied its approach.

When courts ordered desegregation in several schools in Charlottesville and Norfolk, Virginia Gov. James Lindsay Almond Jr. ordered those schools closed. When Almond continued that defiance, 29 of the state’s leading businessmen told him in December 1958 that the crisis was adversely affecting Virginia’s economy. Two months later, the governor proposed a measure to repeal the closure laws and permit desegregation.

On Feb. 2, 1959, 17 Black students in Norfolk and four in Arlington County peacefully enrolled in what had been all-white schools.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

If Tate Reeves calls a tax cut special session, Senate has the option to do nothing

An illness is spreading through the Mississippi Capitol: special session fever.

Speculation is rampant that Gov. Tate Reeves will call a special session if the Senate does not acquiesce to his and the House leadership’s wishes to eliminate the state personal income tax.

Reeves and House leaders are fond of claiming that the about 30% of general fund revenue lost by eliminating the income tax can be offset by growth in other state tax revenue.

House leaders can produce fancy charts showing that the average annual 3% growth rate in state revenue collections can more than offset the revenue lost from a phase out of the income tax.

What is lost in the fancy charts is that the historical 3% growth rate in state revenue includes growth in the personal income tax, which is the second largest source of state revenue. Any growth rate will entail much less revenue if it does not include a 3% growth in the income tax, which would be eliminated if the governor and House leaders have their way. This is important because historically speaking, as state revenue grows so does the cost of providing services, from pay to state employees, to health care costs, to transportation costs, to utility costs and so on.

This does not even include the fact that historically speaking, many state entities providing services have been underfunded by the Legislature, ranging from education to health care, to law enforcement, to transportation. Again, the list goes on and on.

And don’t forget a looming $25 billion shortfall in the state’s Public Employee Retirement System that could create chaos at some point.

But should the Senate not agree to the elimination of the income tax and Reeves calls a special session, there will be tremendous pressure on the Senate leadership, particularly Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann, the chamber’s presiding officer.

Generally speaking, a special session will provide more advantages for the eliminate-the-income-tax crowd.

First off, it will be two against one. When the governor and one chamber of the Legislature are on the same page, it is often more difficult for the other chamber to prevail.

The Mississippi Constitution gives the governor sole authority to call a special session and set an agenda. But the Legislature does have discretion in how that agenda is carried out.

And the Legislature always has the option to do nothing during the special session. Simply adjourn and go home is an option.

But the state constitution also says if one chamber is in session, the other house cannot remain out of session for more than three days.

In other words, theoretically, the House and governor working together could keep the Senate in session all year.

In theory, senators could say they are not going to yield to the governor’s wishes and adjourn the special session. But if the House remained in session, the Senate would have to come back in three days. The Senate could then adjourn again, but be forced to come back if the House stubbornly remained in session.

The process could continue all year.

But in the real world, there does not appear to be a mechanism — constitutionally speaking — to force the Senate to come back. The Mississippi Constitution does say members can be “compelled” to attend a session in order to have a quorum, but many experts say that language would not be relevant to make an entire chamber return to session after members had voted to adjourn.

In the past, one chamber has failed to return to the Capitol and suffered no consequences after the other remained in session for more than three days.

As a side note, the Mississippi Constitution does give the governor the authority to end a special session should the two chambers not agree on adjournment. In the early 2000s, then-Gov. Ronnie Musgrove ended a special session when the House and Senate could not agree on a plan to redraw the state’s U.S. House districts to adhere to population shifts found by the U.S. Census.

But would Reeves want to end the special session without approval of his cherished income tax elimination plan?

Probably not.

In 2002 there famously was an 82-day special session to consider proposals to provide businesses more protection from lawsuits. No effort was made to adjourn that session. It just dragged on until the House finally agreed to a significant portion of the Senate plan to provide more lawsuit protection.

In 1969, a special session lasted most of the summer when the Legislature finally agreed to a proposal of then-Gov. John Bell Williams to opt into the federal Medicaid program.

In both those instances, those wanting something passed — Medicaid in the 1960s and lawsuit protections in the 2000s — finally prevailed.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1898

Feb. 22, 1898

Frazier Baker, the first Black postmaster of the small town of Lake City, South Carolina, and his baby daughter, Julia, were killed, and his wife and three other daughters were injured when a lynch mob attacked.

When President William McKinley appointed Baker the previous year, local whites began to attack Baker’s abilities. Postal inspectors determined the accusations were unfounded, but that didn’t halt those determined to destroy him.

Hundreds of whites set fire to the post office, where the Bakers lived, and reportedly fired up to 100 bullets into their home. Outraged citizens in town wrote a resolution describing the attack and 25 years of “lawlessness” and “bloody butchery” in the area.

Crusading journalist Ida B. Wells wrote the White House about the attack, noting that the family was now in the Black hospital in Charleston “and when they recover sufficiently to be discharged, they) have no dollar with which to buy food, shelter or raiment.

McKinley ordered an investigation that led to charges against 13 men, but no one was ever convicted. The family left South Carolina for Boston, and later that year, the first nationwide civil rights organization in the U.S., the National Afro-American Council, was formed.

In 2019, the Lake City post office was renamed to honor Frazier Baker.

“We, as a family, are glad that the recognition of this painful event finally happened,” his great-niece, Dr. Fostenia Baker said. “It’s long overdue.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed3 days agoJeff Landry’s budget includes cuts to Louisiana’s domestic violence shelter funding

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed3 days agoBills from NC lawmakers expand gun rights, limit cellphone use

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed4 days ago

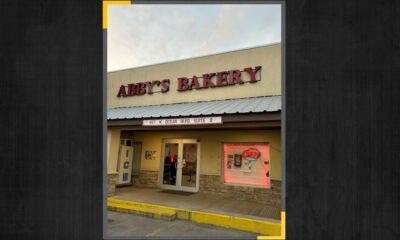

News from the South - Texas News Feed4 days agoICE charges Texas bakery owners with harboring immigrants

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days agoRemains of Aubrey Dameron found, family gathers in her honor

-

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed9 hours ago

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed9 hours ago‘What’s next?’: West Virginia native loses dream job during National Park Service terminations

-

Mississippi Today7 days ago

Mississippi Today7 days agoMississippi could face health research funding cuts under Trump administration policy

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days agoTrump says AP will continue to be curtailed at White House until it changes style to Gulf of America

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days agoInterstate 44 reopens following mass traffic