Amputees in 16th century Europe commissioned iron hands from artisans, many of whom had never made prostheses before.

Heidi Hausse, Auburn University

The human body today has many replaceable parts, ranging from artificial hearts to myoelectric feet. What makes this possible is not just complicated technology and delicate surgical procedures. It’s also an idea — that humans can and should alter patients’ bodies in supremely difficult and invasive ways.

Where did that idea come from?

Scholars often depict the American Civil War as an early watershed for amputation techniques and artificial limb design. Amputations were the most common operation of the war, and an entire prosthetics industry developed in response. Anyone who has seen a Civil War film or TV show has likely watched at least one scene of a surgeon grimly approaching a wounded soldier with saw in hand. Surgeons performed 60,000 amputations during the war, spending as little as three minutes per limb.

Yet, a momentous change in practices surrounding limb loss started much earlier – in 16th and 17th century Europe.

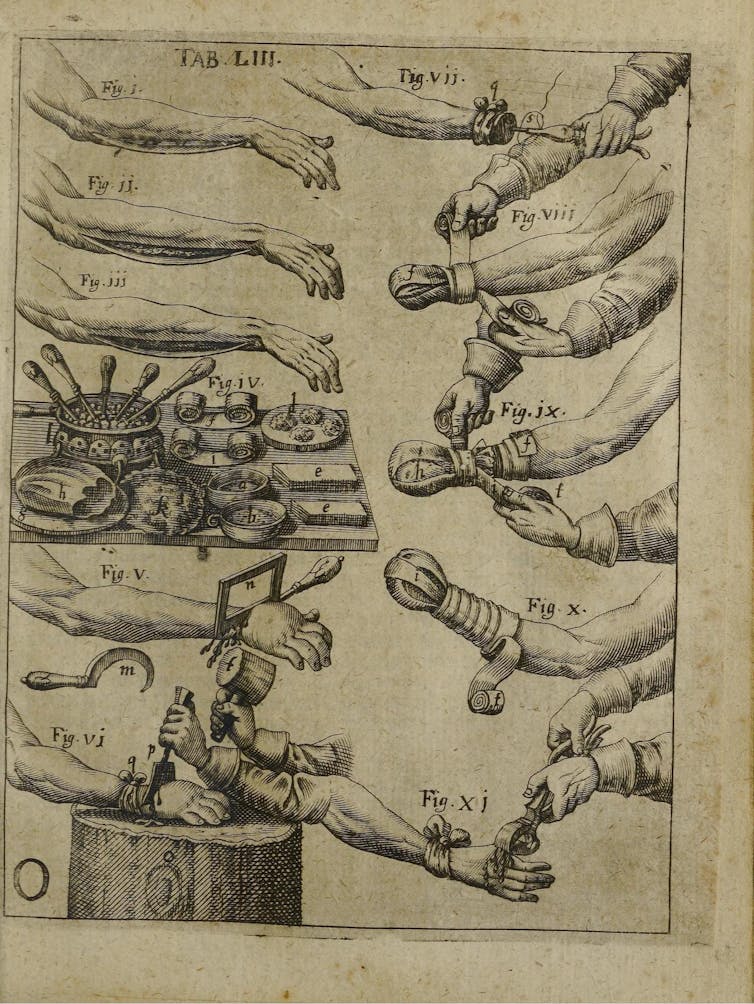

The surgeon Ambroise Paré printed a Parisian locksmith’s design for a mechanical iron hand in the 16th century. Instrumenta chyrurgiae et icones anathomicae/Ambroise Paré via Wellcome Collection

As a historian of early modern medicine, I explore how Western attitudes toward surgical and artisanal interventions in the body started transforming around 500 years ago. Europeans went from hesitating to perform amputations and few options for limb prostheses in 1500 to multiple amputation methods and complex iron hands for the affluent by 1700.

Amputation was seen as a last resort because of the high risk of death. But some Europeans started to believe they could use it along with artificial limbs to shape the body. This break from a millennia-long tradition of noninvasive healing still influences modern biomedicine by giving physicians the idea that crossing the physical boundaries of the patient’s body to drastically change it and embed technology into it could be a good thing. A modern hip replacement would be unthinkable without that underlying assumption.

Surgeons, gunpowder and the printing press

Early modern surgeons passionately debated where and how to cut the body to remove fingers, toes, arms and legs in ways medieval surgeons hadn’t. This was partly because they confronted two new developments in the Renaissance: the spread of gunpowder warfare and the printing press.

Surgery was a craft learned through apprenticeship and years of traveling to train under different masters. Topical ointments and minor procedures like setting broken bones, lancing boils and stitching wounds filled surgeons’ day-to-day practice. Because of their danger, major operations like amputations or trepanations – drilling a hole in the skull – were rare.

Widespread use of firearms and artillery strained traditional surgical practices by tearing bodies apart in ways that required immediate amputation. These weapons also created wounds susceptible to infection and gangrene by crushing tissue, disrupting blood flow and introducing debris — ranging from wood splinters and metal fragments to scraps of clothing — deep into the body. Mangled and gangrenous limbs forced surgeons to choose between performing invasive surgeries or letting their patients die.

The printing press gave surgeons grappling with these injuries a means to spread their ideas and techniques beyond the battlefield. The procedures they described in their treatises can sound gruesome, particularly because they operated without anesthetics, antibiotics, transfusions or standardized sterilization techniques.

A 17th century treatise instructs surgeons to use a mallet and chisel among other amputation methods.

But each method had an underlying rationale. Striking off a hand with a mallet and chisel made the amputation quick. Cutting through desensitized, dead flesh and burning away the remaining dead matter with a cautery iron prevented patients from bleeding to death.

While some wanted to save as much of the healthy body as possible, others insisted it was more important to reshape limbs so patients could use prostheses. Never before had European surgeons advocated amputation methods based on the placement and use of artificial limbs. Those who did so were coming to see the body not as something the surgeon should simply preserve, but rather as something the surgeon could mold.

Amputees, artisans and artificial limbs

As surgeons explored surgical intervention with saws, amputees experimented with making artificial limbs. Wooden peg devices, as they’d been for centuries, remained common lower limb prostheses. But creative collaborations with artisans were the driving force behind a new prosthetic technology that began appearing in the late 15th century: the mechanical iron hand.

Written sources reveal little about the experiences of most who survived limb amputation. Survival rates may have been as low as 25%. But among those who made it through, artifacts show improvisation was key to how they navigated their environments.

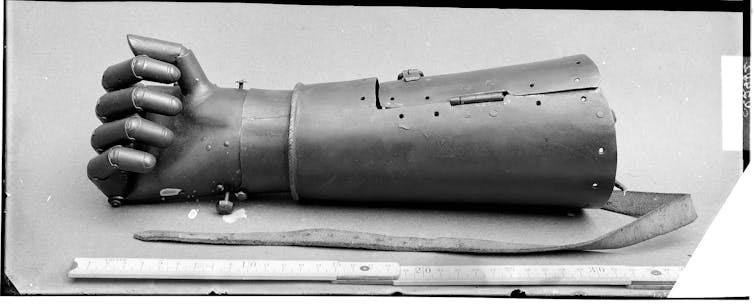

A wearer operated this 16th century iron hand by pressing down on the fingers to lock them and pressing the release button at the top of the wrist to free them.

This reflected a world in which prosthetics were not yet “medical.” In the U.S. today, a doctor’s prescription is necessary for an artificial limb. Early modern surgeons sometimes provided small devices like artificial noses, but they didn’t design, make or fit prosthetic limbs. Furthermore, there was no occupation comparable to today’s prosthetists, or health care professionals who make and fit prostheses. Instead, early modern amputees used their own resources and ingenuity to have ones made.

Iron hands were improvised creations. Their movable fingers locked into different positions through internal spring-driven mechanisms. They had lifelike details: engraved fingernails, wrinkles and even flesh-toned paint.

Wearers operated them by pressing down on the fingers to lock them into position and activating a release at the wrist to free them. In some iron hands the fingers move together, while in others they move individually. The most sophisticated are flexible in every joint of every finger.

Complex movement was more for impressing observers than everyday practicality. Iron hands were the Renaissance precursor to the “bionic-hand arms race” of today’s prosthetics industry. More flashy and high-tech artificial hands – then and now – are also less affordable and user-friendly.

This technology drew from surprising places, including locks, clocks and luxury handguns. In a world without today’s standardized models, early modern amputees commissioned prostheses from scratch by venturing into the craft market. As one 16th century contract between an amputee and a Genevan clockmaker attests, buyers dropped into the shops of artisans who’d never made a prosthesis to see what they could concoct.

Because these materials were often expensive, wearers tended to be wealthy. In fact, the introduction of iron hands marks the first time period when European scholars can readily distinguish between people of different social classes based on their prostheses.

Powerful ideas

Iron hands were important carriers of ideas. They prompted surgeons to think about prosthesis placement when they operated and created optimism about what humans could achieve with artificial limbs.

But scholars have missed how and why iron hands made this impact on medical culture because they’ve been too fixated on one kind of wearer – knights. Traditional assumptions that injured knights used iron hands to hold the reins of their horses offer only one narrow view of surviving artifacts.

A famous example colors this interpretation: the “second hand” of the 16th century German knight Götz von Berlichingen. In 1773, the playwright Goethe drew loosely from Götz’s life for a drama about a charismatic and fearless knight who dies tragically, wounded and imprisoned, while exclaiming “Freedom – freedom!”. (The historical Götz died of old age.)

A 19th century photograph of the famous ‘second hand’ of Götz von Berlichingen with flexible finger joints.

Götz’s story has inspired visions of a bionic warrior ever since. Whether in the 18th century or the 21st, you can find mythical depictions of Götz standing defiant in the face of authority and clutching a sword in his iron hand – an impractical feat for his historical prosthesis. Until recently, scholars supposed all iron hands must have belonged to knights like Götz.

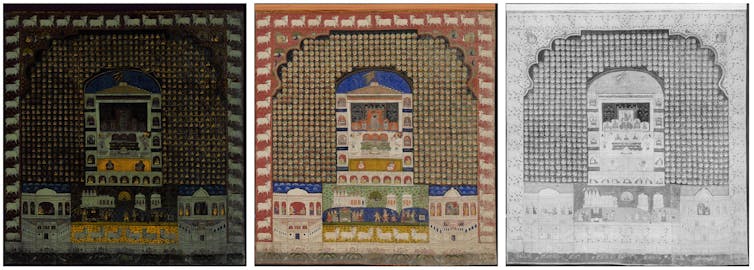

But my research reveals that many iron hands show no signs of having belonged to warriors, or perhaps even to men. Cultural pioneers, many of whom are known only from the artifacts they left behind, drew on stylish trends that prized clever mechanical devices, like the miniature clockwork galleon displayed today at the British museum. In a society that coveted ingenious objects blurring the boundaries between art and nature, amputees used iron hands to defy negative stereotypes depicting them as pitiable. Surgeons took note of these devices, praising them in their treatises. Iron hands spoke a material language contemporaries understood.

Before the modern body of replaceable parts could exist, the body had to be reimagined as something humans could mold. But this reimagining required the efforts of more than just surgeons. It also took the collaboration of amputees and the artisans who helped construct their new limbs.

Heidi Hausse, Assistant Professor of History, Auburn University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.