Mississippi Today

Mississippi’s no-knock raids have led to death and injury. Dozens of warrants lacked clear justification.

by Caleb Bedillion, The Marshall Project, Mississippi Today

March 20, 2025

This article was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system, and the Daily Journal. Sign up for The Marshall Project’s Jackson newsletter, and follow them on Instagram, TikTok, Reddit and Facebook.

During a 2015 no-knock drug raid in Mississippi’s rural northeast corner, sheriff’s deputies shot and killed 57-year-old Ricky Keeton after he came to the door with an air pistol as SWAT team members forced their way into his trailer home at 1 a.m.

Keeton’s death received little public attention at the time. Keeton’s three daughters sued, arguing that Monroe County deputies had no constitutional authority that night to burst into their father’s home with a battering ram and pry bar without first knocking and identifying themselves.

The federal wrongful death suit was settled seven years later for $690,000. This came after several judges refused to dismiss the lawsuit, ruling the defendants failed to prove there was any legal justification for the no-knock raid in the first place. The county and sheriff’s department made no admission of wrongdoing in the settlement.

Five years after Keeton’s death, no-knock searches faced increased national scrutiny after police shot and killed Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky, during a March 2020 raid in which her boyfriend shot and wounded an officer. The boyfriend later said he thought they were intruders. Similarly, Keeton’s girlfriend said that Keeton “thought somebody was breaking in” before he was shot to death.

Taylor’s shooting death ultimately amplified longstanding, bipartisan demands for reform of no-knock raids. Several states limited no-knock searches, including Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia.

Mississippi has a history of no-knock searches — with dangerous results. Police have raided the wrong homes, and in one 2020 case, officers even shot and wounded an unarmed person visiting a targeted home.

Yet as other states tightened their no-knock search laws, Mississippi officials did nothing.

Since the Keeton killing in 2015, judges in six courts across the state have approved at least 62 no-knock search warrants that failed to show that they met basic constitutional standards, an investigation by The Marshall Project – Jackson and the Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal found.

The news organizations showed copies of the warrants from across the state to legal experts including attorneys, law professors and former federal magistrates. The experts agreed that most of the search warrants and affidavits showed no written legal justification for the no-knock warrants.

One of those courts was in Monroe County, where, for years after Keeton’s death and the lawsuit that followed, some county-level judges continued to sign what experts deemed legally threadbare no-knock search warrants.

The Supreme Court has ruled that to obtain a no-knock search warrant from a judge, police must show that the search target is dangerous or might try to run away or destroy evidence. Experts said the vast majority of warrants and affidavits gathered by The Marshall Project – Jackson and the Daily Journal didn’t state an adequate reason — if they had one at all.

“You’ve got a real mess on your hands,” said Henry Schultz, a Wisconsin-based attorney who reviewed those files for the news outlets. Some 25 years ago, Schultz helped argue the key 1997 case in which the U.S. Supreme Court required specific limits on no-knock searches.

Pointing to the search warrants from Mississippi, Schultz said the high court’s attempt to put guardrails around no-knock raids nearly three decades ago isn’t working.

There has never been a public survey of no-knock warrants in Mississippi, where many courts block access to search warrant records.

After rising scrutiny focused on Monroe County, including this reporting effort, officials there scuttled the use of boilerplate no-knock search warrant requests about two years ago.

In at least two other Mississippi courts, no-knock search warrants dropped off in recent years, according to records reviewed this year by the news outlets.

Beyond these local changes, there’s still no broader oversight of how judges in the state handle no-knock requests and no easy way to check up on them.

With no statewide restrictions, judges can disregard Supreme Court precedent at any time, with few consequences.

Judges across the country have largely avoided the same level of scrutiny that has fallen on police departments and even prosecutors over no-knock warrant abuses, said Christy Lopez, a former U.S. Department of Justice attorney, and one of the legal experts who reviewed the news outlets’ findings.

She said the investigation in Mississippi by The Marshall Project – Jackson and the Daily Journal shows that judges must reckon with their share of the responsibility.

“Judges,” said Lopez, “are really failing people on no-knocks.”

In January 2020, Brandon Davis traded his deputy sheriff’s badge for a judge’s gavel after defeating an incumbent’s bid for reelection. By then, litigation over Ricky Keeton’s death was entering its fifth year.

Davis joined the bench of the Monroe County Justice Court with another newly elected judge, Sarah Cline Stevens, an attorney specializing in family law matters. Her legal education is a rarity among justice court judges in Mississippi. These judges aren’t required to be lawyers and usually only hear small civil claims and misdemeanor criminal matters. They can also sign search warrants.

During a career of more than a decade-and-a-half in law enforcement, Davis joined many no-knock raids with the Monroe County Sheriff’s Office. In some cases, he prepared the actual applications and presented them to a judge. He didn’t play any role in the Keeton raid.

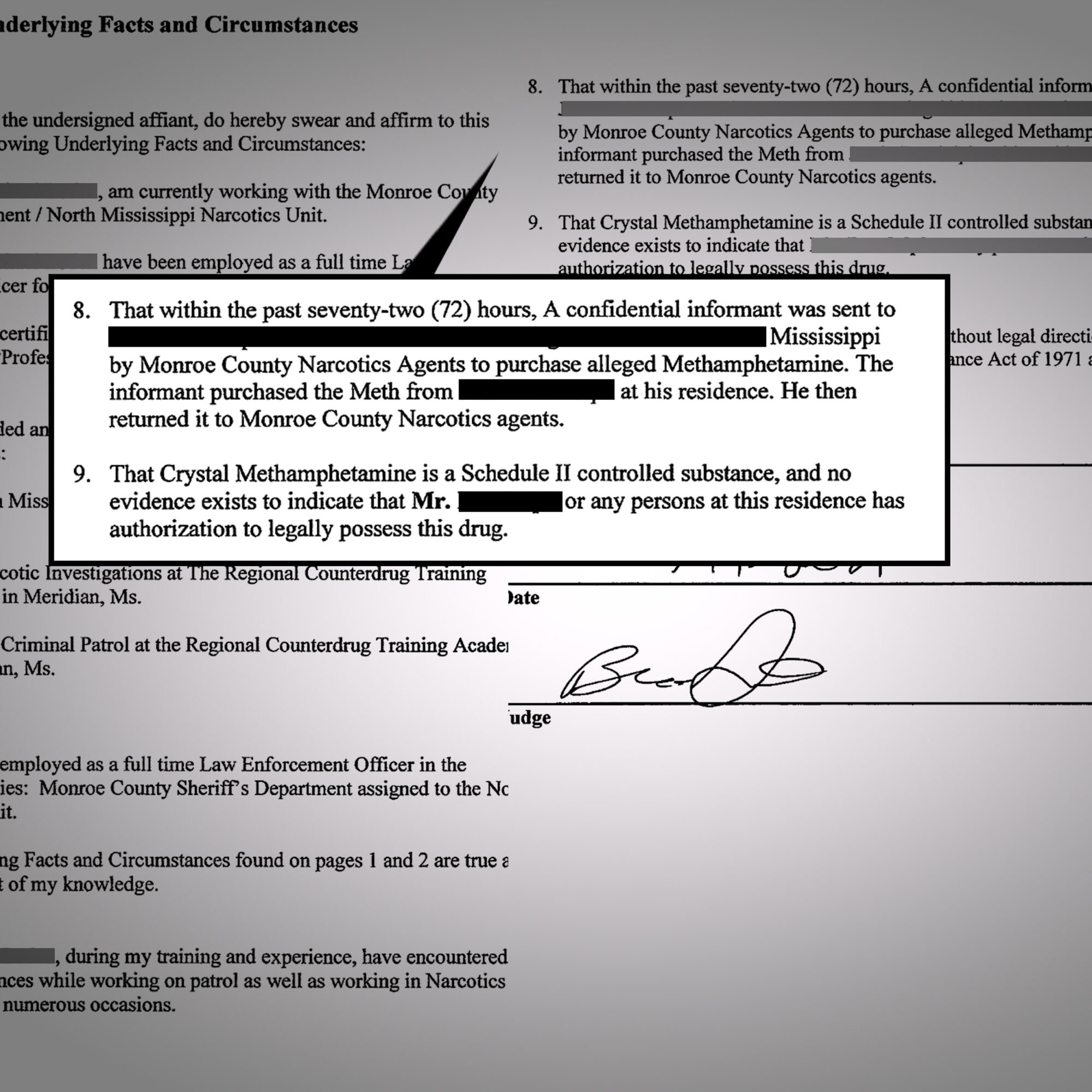

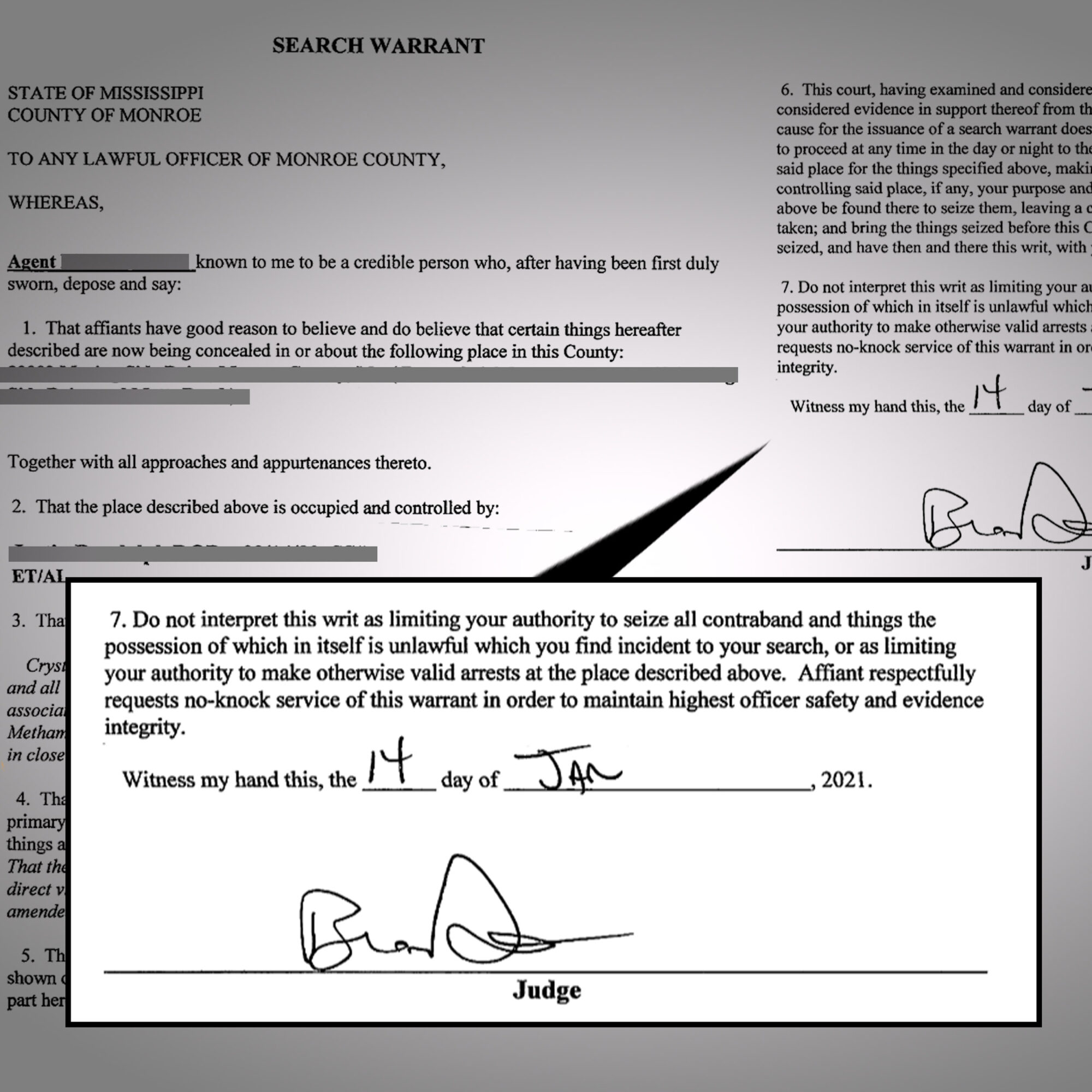

The same month he took office, court records show, Davis signed a search warrant for a Monroe County deputy.

It authorized no-knock entry.

It also repeated the major flaws of the search warrant used in the Keeton raid.

The only reference to a no-knock entry was a boilerplate sentence near the end of the search warrant — a sentence that has appeared in Monroe County search warrants in some form over many years: “The above affiant respectfully requests a no-knock search due to officer safety and the protection of further evidence.”

Neither the warrant that Davis signed nor the written affidavit that’s required to support it offered any detailed, written reasons for the no-knock request.

U.S. District Judge Sharion Aycock zeroed in on the lack of any details, written or otherwise, in the Keeton no-knock warrant during the family’s lawsuit against Monroe County and sheriff’s deputies.

“The Defendants have failed to bring forth any evidence that announcing their presence, ‘under the particular circumstances’ was dangerous,” Aycock wrote in a 2018 order dismissing Monroe County’s motion to drop the case.

The U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with Aycock a year later.

Monroe County Justice Court Judge Stevens, a lawyer, was aware of the Keeton litigation when she joined the bench, and said in a 2022 interview that she studied the legal issues involved.

The homework paid off.

She received a search warrant application in February 2020. It contained the boilerplate no-knock request. She signed it, but only after handwriting additional notes on the affidavit, culled from an interview of the officer: The targeted person had been served two prior search warrants before and “he came to the door with a gun (sawed off shotgun and pistol).” A confidential informant also told officers, “Weapons are currently present.”

![A search warrant with two blocks of highlighted text that read: “The confidential informant also sent pictures of methamphetamine inside the residence and the shop behind the residence to Agent [redacted],” and “8. That within the past seventy-two (72) hours, a confidential informant contacted Agent [redacted] with the Monroe County Sheriff’s Department and stated that at [redacted] had methamphetamine inside the residence and inside the shop behind the residence.” Judge Sarah Stevens’ initials are signed near both highlighted texts.](https://cdn.mississippitoday.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/19215558/250319-NOKNOCKS-Annotation-Stevens-1-v3.jpg)

![A search warrant with highlighted text that shows handwritten notes by Justice Court Judge Sarah Cline Stevens: “Suspect [redacted] has previously been the person of interest under search warrants and on two different occasions he came to the door with a gun (sawed off shotgun and pistol). Highly probable that suspect will attempt to dispose of the drugs etc. if their presence is announced. Suspect is armed and dangerous. CI stated that weapons are currently present.”](https://cdn.mississippitoday.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/19215558/250319-NOKNOCKS-Annotation-Stevens-2-v4.jpg)

That’s the level of specific detail that the Supreme Court’s 1997 ruling, Richards v. Wisconsin, requires, experts agreed. Lopez, the former Justice Department attorney, said the high court set a fairly low bar — too low in her view.

Nonetheless, for years, most no-knock search warrants in Monroe County failed to clear even that low bar.

The news organizations found 14 no-knock warrants signed by Monroe County Justice Court judges since 2015, with the last such warrant found in late 2022. Since 2020, when Davis and Stevens joined the bench, court records show 11 no-knock search warrants have been signed, almost all of them by Davis, the former sheriff’s deputy.

Experts said they found all but one warrant lacking adequate written justification. Stevens signed the one with adequate support, as well as one of the 11 without adequate written support. Davis signed most of the rest, with a third judge, Adrian Haynes, signing only one. Haynes did not respond to a request for comment.

Judges and the court clerk said that the court records reviewed by The Marshall Project – Jackson and the Daily Journal are incomplete, meaning the judges may have signed even more no-knock search warrants.

Stephen Smith, a retired federal magistrate from Texas, often reviewed search warrant applications during his judicial career. After looking at some of the Monroe County search warrants, he said he wouldn’t have signed them as no-knock searches.

“Every one of these granted no-knock authority,” he said, “and only one attempted to justify it.”

In a 2022 interview, Davis said he was granting no-knock search warrants to preserve officer safety and to prevent the destruction of evidence, though neither the search warrants nor the affidavits showed sufficient written evidence from the cases at hand to support those justifications.

Davis said that he often discussed a search warrant affidavit with the requesting officer, but that he didn’t document the conversations in writing. In Mississippi, judges can rely on sworn oral testimony beyond the affidavit in support of a search warrant. There’s no requirement to document it in writing, but Davis said that in mandatory training sessions for justice court judges that he attended, the judges were advised to do so.

“They’re telling us, you really need to include this, it needs to be on paper,” Davis said.

Jeffrey B. Welty, who teaches law in North Carolina and also helps train judges there, strongly advises against interviewing officers about their applications, especially if it won’t be documented in some fashion.

“Don’t have them tell you a bunch of stuff about the case that doesn’t appear in the application, because that’s just fraught with peril,” Welty said he tells judges. “That doesn’t seem like a good judicial practice to me.”

Davis also described approving search warrants in some cases based on his knowledge of suspects from his career in law enforcement. But judges should not rely on their own knowledge of people or places described in a warrant application; they should consider information supplied by the officer, said William Waller Jr., a retired justice of the Mississippi Supreme Court.

In response to Waller and others who reviewed his warrants, Davis in early 2025 said that he stands by the fairness of his process.

“Opinions are just that, opinions. That’s what you got when you asked other retired judges or lawyers,” said Davis. “If I am wrong, then why have I not been disciplined?”

He also added, “If the people don’t like my decisions, then they can elect another judge next election.”

Over the course of a years-long reporting effort by The Marshall Project – Jackson and the Daily Journal, Monroe County’s judicial practices changed.

After that 2022 interview by the news organizations with Davis and Stevens, Davis began amending applications for no-knock search warrants with handwritten notes, though experts said they found his level of detail was still lacking. In 2023, Davis said he was doing so because of increasing scrutiny on courts.

“The last thing I want is for anybody to question my decision on something,” said Davis in 2023. “You have more people now that’s looking at the judicial system.”

A new sheriff, Kevin Crook, took office in 2020, the same year Davis and Stevens joined the bench. Crook, a former sheriff’s deputy and justice court judge, soon began to field questions about the county’s no-knock practices as local and national news investigations scrutinized the county amid the rising national outrage that year over Breonna Taylor’s death.

Crook told The Marshall Project – Jackson and the Daily Journal in 2023 that the no-knock search warrants located by the news organizations weren’t always executed as no-knock searches and that his department was moving away from what he deemed “crazy tactics” used by the department when executing no-knock search warrants in years past.

In 2023, Davis also said that he was seeing fewer no-knock search warrant requests from officers.

And after those 2023 interviews, officials changed course even further.

“We took the language out,” Crook said in early 2025, referring to the boilerplate language in previous no-knock warrants. “If we need it, we are going to explain to the judge why we need it.”

Search warrants on file with the court bear this out. The boilerplate no-knock language disappeared from search warrants. The judges also instituted an on-call rotation to handle search warrant applications, an initiative intended in part to prevent the appearance that deputies were taking their warrant applications directly to a favored judge.

“This has been an issue that has brought a lot of negative light to our county,” said Stevens. “It’s something that I’ve been very sensitive to from the beginning of my first term.”

About an hour up the road from the courthouse where Davis and Stevens preside sits the Pontotoc County Justice Court, nestled in the Hills Region of northeast Mississippi.

Court records in Pontotoc County show that the justice court’s two long-serving judges, David Hall and Scottie Harrison, together signed 33 no-knock search warrants from 2020 through 2023.

After an apparent reorganization of the county’s drug task force in late 2023, court records do not show the authorization of any more no-knock searches.

But for the records examined from 2020 through 2023, no-knock searches were almost half of all search warrants found in court records. Almost all of the search warrants examined in drug cases contained no-knock permission.

Legal experts who reviewed the documents agreed that with only three exceptions, those Pontotoc County search warrants lacked written justification for no-knock entry because they failed to offer any facts to support the claim that officers might be in danger, or that suspects might escape or destroy evidence. In some cases, those experts said there didn’t even appear to be adequate written justification for a search warrant of any kind.

Hall and Harrison did not respond to requests for comment.

Including Pontotoc and Monroe counties, the news organizations found 91 no-knock search warrants, with 62 of those warrants deemed legally defective by experts . These warrants were signed by 10 judges in six jurisdictions from across the state from 2015 through 2023.

In total, the news organizations reviewed records from 20 courts looking for no-knock search warrants, reviewing thousands of pages of court filings and submitting dozens of public record requests.

Many of these no-knock search warrants contained no explanation for why a no-knock search was needed, either by the issuing judge or the requesting officer.

“Facts matter; specifics matter,” said Brian Owsley, a retired federal magistrate judge from Texas who signed hundreds of search warrants while on the bench. “Are the targets dangerous? Are they armed? Are they armed and apt to shoot?”

That’s where Mississippi’s no-knock search warrants so often go wrong.

“In these warrants, I don’t really see that discussion at all,” Owsley said.

Other search warrants offer only meager supporting evidence, including anonymous phone calls or old information. Some of these warrants were directed toward locations where a no-knock entry doesn’t seem necessary. In Pontotoc County, Hall signed two no-knock warrants authorizing searches of gas stations. The written application didn’t request no-knock authority.

Two search warrants signed by Ricky Farmer, a former justice court judge in Stone County, near the Gulf Coast, authorized no-knock entry to search unoccupied cars at towing lots. These applications also didn’t ask for no-knock permission.

Some warrants were rife with sloppiness and sometimes even possible errors, said several experts, including Welty, who trains judges in North Carolina.

Another warrant from Stone County signed by Farmer directed officers to search one address in the warrant, but the requesting affidavit contained an entirely different address outside the judge’s jurisdiction. The mistake was likely due to a copying error on the warrant.

Farmer did not respond to requests for comment.

Unlike justice courts in Pontotoc and Monroe counties, some courts offered a more mixed bag. In the Southaven and Greenville municipal courts, the news organizations found a number of no-knock search warrants that did contain sufficient written justification alongside a few warrants that experts said did not.

In Southaven, municipal court judges haven’t issued a no-knock search warrant since 2020.

Unlike justice court judges, municipal court judges in Mississippi typically have law degrees.

But whether these kinds of warrants are rising, declining or holding steady, judges should handle no-knock requests with particular care given the potentially dangerous and even lethal consequences, said civil rights attorneys and legal experts.

For a judge to do otherwise, said Lopez, the former Justice Department attorney, is “shocking” and shows “no sense of the potential harm of what they’re doing.”

In the Mississippi city of Vicksburg, an elderly couple sued after state narcotics agents raided their home by mistake with a no-knock search warrant in hand and forced them onto the ground at gunpoint. A judge awarded them $50,000 in 2019. Two other lawsuits in the state involving death or serious injuries during no-knock raids have been settled since 2022, including the Keeton litigation. Two additional lawsuits over no-knock raids remain ongoing, including a case in Jones County involving mistaken entry at the wrong apartment.

The search warrant problems uncovered by this investigation are by no means unique to Mississippi. Welty conducted a similar review of no-knock search warrants in North Carolina. He said the legal justifications offered were better than the Mississippi search warrants he reviewed, but they were still sometimes thin.

In 2018, a Washington Post columnist found search warrants from Arkansas lacking any legally sufficient reason for no-knock entry. A larger investigation in 2020 by the news outlet found hasty, superficial reviews of no-knock search warrant applications across the county.

Even the search warrant used in the deadly Breonna Taylor raid — one of five similar no-knock search warrants police had obtained — lacked legal justification for a no-knock entry, according to some legal observers.

Looking back at his involvement in the key 1997 case from the U.S. Supreme Court, Schultz, the attorney in Wisconsin, said the ruling felt significant at the time.

“For a while, it looked like things were going to change,” he remembered.

But in a later 2006 opinion, the high court said that even when police unlawfully force their way into a home, they can still use evidence seized in the raid. Other violations of the Fourth Amendment typically bar prosecutors from using any evidence seized in court.

Civil rights advocates have frequently blamed that 2006 ruling for undermining the significance of prior rulings limiting no-knock entries.

Schultz agreed. Taking stock of the Mississippi search warrants he reviewed and the absence of larger reforms in the state as well as many other parts of the country, that 1997 Supreme Court ruling often doesn’t feel like it matters much anymore.

“We’re back to where we were,” said Schultz. “It’s kind of depressing that we would be in this spot.”

Some reporting for this article was done with the support of ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network.

How we reported the story

No one tracks or monitors search warrants in Mississippi. Statewide rules for courts do require that search warrants must be returned to court, however, and filed by the clerk.

As previously reported by the Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal and ProPublica, many courts violate court rules and don’t actually have these records. Others do have them on file but refuse to make them available to the public.

However, The Marshall Project – Jackson and the Daily Journal continued a years-long effort to obtain search warrants where they were available. We visited courthouses and looked through thousands of pages of court files, scoured electronic court records and submitted dozens of public records requests.

Ultimately, we gathered search warrants from 20 different jurisdictions, focusing primarily on justice courts, where judges often have no law degree and frequently authorize search warrants, but also including some municipal courts.

Some document caches were well-organized and went back many years. In other places, clerks had incomplete records, or even no records, and we only obtained a few search warrants.

Of the 20 courts where we obtained search warrants, six had at least some no-knock search warrants. Pontotoc County Justice Court and the Greenville Municipal Court each had more than 20.

In some of the places where the news organizations found some no-knock search warrants, search warrant records are not widely available from the court, making it difficult to assess how frequently no-knock search warrants have been issued or if they are still being issued.

The final reporting looked only at search warrants signed within the last decade.

In some counties with lawsuits over alleged no-knock raids, including Coahoma County, there were no judicially authorized no-knock search warrants among the court records. In other places with no-knock search warrants among the files, including Monroe County, law enforcement officials claimed that such warrants aren’t always, or even normally, executed as no-knock searches.

Law enforcement officers can also execute a standard knock-and-announce search warrant with a no-knock entry based on emergency conditions at the time the warrant is executed.

We asked eight legal experts to review the warrants and accompanying affidavits that we found and to evaluate their legal justification under the requirements of the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in a 1997 case, Richards v. Wisconsin.

These experts included retired federal magistrates, who frequently handled search warrant requests from the federal bench, as well as practicing attorneys and law professors.

No one expert reviewed the entire batch of records. To ensure a diversity of viewpoints, we showed some of the same search warrants to multiple experts. Experts consistently agreed about which no-knock search warrant requests were justified with written support and which were not.

Here are the places where we found no-knock search warrants, with the total number of no-knock search warrants since 2015 and the total number of no-knock search warrants without written support:

Greenville Municipal Court: 23 no-knock search warrants, eight without written support. All were signed by Municipal Court Judge Michael Prewitt.

Monroe County Justice Court: 15 no-knock search warrants, 14 without written support. Most signed by Monroe County Justice Court Judge Brandon Davis. Two signed by Monroe County Justice Court Judge Sarah Cline Stevens. One signed by Monroe County Justice Court Judge Adrian Haynes. Stevens signed the only no-knock search warrant identified in this county with sufficient written support.

Pontotoc County Justice Court: 33 no-knock search warrants, 30 without written support. All were signed by Pontotoc County Justice Court Judges David Hall and Scottie Harrison.

Southaven Municipal Court: 13 no-knock search warrants, five without written support. Of the 13 total no-knock search warrants, 10 were signed by Southaven Municipal Court Judge David Delgado, and three were signed by Southaven Municipal Court Judge Joseph Neyman. Of the five without sufficient written support, Delgado signed four and Neyman signed one.

Stone County Justice Court: Six no-knock search warrants, four without written support. All were signed by former Stone County Justice Court Judge Ricky Farmer.

Yazoo County Justice Court: One no-knock search warrant, one without written support. Signed by Yazoo County Justice Court Judge Pam May.

Only Judges Davis and Stevens from Monroe County agreed to interviews or responded to requests for comments. Their comments are in the story. The remaining judges did not respond to requests for comment.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

Speaker White wants Christmas tree projects bill included in special legislative session

House Speaker Jason White sent a terse letter to Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann on Thursday, saying House leaders are frustrated with Senate leaders refusing to discuss a “Christmas tree” bill spending millions on special projects across the state.

The letter signals the two Republican leaders remain far apart on setting an overall $7 billion state budget. Bickering between the GOP leaders led to a stalemate and lawmakers ending their regular 2025 session without setting a budget. Gov. Tate Reeves plans to call them back into special session before the new budget year starts July 1 to avoid a shutdown, but wants them to have a budget mostly worked out before he does so.

White’s letter to Hosemann, which contains words in all capital letters that are underlined and italicized, said that the House wants to spend cash reserves on projects for state agencies, local communities, universities, colleges, and the Mississippi Department of Transportation.

“We believe the Senate position to NOT fund any local infrastructure projects is unreasonable,” White wrote.

The speaker in his letter noted that he and Hosemann had a meeting with the governor on Tuesday. Reeves, according to the letter, advised the two legislative leaders that if they couldn’t reach an agreement on how to disburse the surplus money, referred to as capital expense money, they should not spend any of it on infrastructure.

A spokesperson for Hosemann said the lieutenant governor has not yet reviewed the letter, and he was out of the office on Thursday working with a state agency.

“He is attending Good Friday services today, and will address any correspondence after the celebration of Easter,” the spokesperson said.

Hosemann has recently said the Legislature should set an austere budget in light of federal spending cuts coming from the Trump administration, and because state lawmakers this year passed a measure to eliminate the state income tax, the source of nearly a third of the state’s operating revenue.

Lawmakers spend capital expense money for multiple purposes, but the bulk of it — typically $200 million to $400 million a year — goes toward local projects, known as the Christmas Tree bill. Lawmakers jockey for a share of the spending for their home districts, in a process that has been called a political spoils system — areas with the most powerful lawmakers often get the largest share, not areas with the most needs. Legislative leaders often use the projects bill as either a carrot or stick to garner votes from rank and file legislators on other issues.

A Mississippi Today investigation last year revealed House Ways and Means Chairman Trey Lamar, a Republican from Sentobia, has steered tens of millions of dollars in Christmas tree spending to his district, including money to rebuild a road that runs by his north Mississippi home, renovate a nearby private country club golf course and to rebuild a tiny cul-de-sac that runs by a home he has in Jackson.

There is little oversight on how these funds are spent, and there is no requirement that lawmakers disburse the money in an equal manner or based on communities’ needs.

In the past, lawmakers borrowed money for Christmas tree bills. But state coffers have been full in recent years largely from federal pandemic aid spending, so the state has been spending its excess cash. White in his letter said the state has “ample funds” for a special projects bill.

“We, in the House, would like to sit down and have an agreement with our Senate counterparts on state agency Capital Expenditure spending AND local projects spending,” White wrote. “It is extremely important to our agencies and local governments. The ball is in your court, and the House awaits your response.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mississippi Today

Advocate: Election is the chance for Jackson to finally launch in the spirit of Blue Origin

Editor’s note: This essay is part of Mississippi Today Ideas, a platform for thoughtful Mississippians to share fact-based ideas about our state’s past, present and future. You can read more about the section here.

As the world recently watched the successful return of Blue Origin’s historic all-women crew from space, Jackson stands grounded. The city is still grappling with problems that no rocket can solve.

But the spirit of that mission — unity, courage and collective effort — can be applied right here in our capital city. Instead of launching away, it is time to launch together toward a more just, functioning and thriving Jackson.

The upcoming mayoral runoff election on April 22 provides such an opportunity, not just for a new administration, but for a new mindset. This isn’t about endorsements. It’s about engagement.

It’s a moment for the people of Jackson and Hinds County to take a long, honest look at ourselves and ask if we have shown up for our city and worked with elected officials, instead of remaining at odds with them.

It is time to vote again — this time with deeper understanding and shared responsibility. Jackson is in crisis — and crisis won’t wait.

According to the U.S. Census projections, Jackson is the fastest-shrinking city in the United States, losing nearly 4,000 residents in a single year. That kind of loss isn’t just about numbers. It’s about hope, resources, and people’s decision to give up rather than dig in.

Add to that the long-standing issues: a crippled water system, public safety concerns, economic decline and a sense of division that often pits neighbor against neighbor, party against party and race against race.

Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba has led through these storms, facing criticism for his handling of the water crisis, staffing issues and infrastructure delays. But did officials from the city, the county and the state truly collaborate with him or did they stand at a distance, waiting to assign blame?

On the flip side, his runoff opponent, state Sen. John Horhn, who has served for more than three decades, is now seeking to lead the very city he has represented from the Capitol. Voters should examine his legislative record and ask whether he used his influence to help stabilize the administration or only to position himself for this moment.

Blaming politicians is easy. Building cities is hard. And yet that is exactly what’s needed. Jackson’s future will not be secured by a mayor alone. It will take so many of Jackson’s residents — voters, business owners, faith leaders, students, retirees, parents and young people — to move this city forward. That’s the liftoff we need.

It is time to imagine Jackson as a capital city where clean, safe drinking water flows to every home — not just after lawsuits or emergencies, but through proactive maintenance and funding from city, state and federal partnerships. The involvement of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in the effort to improve the water system gives the city leverage.

Public safety must be a guarantee and includes prevention, not just response, with funding for community-based violence interruption programs, trauma services, youth job programs and reentry support. Other cities have done this and it’s working.

Education and workforce development are real priorities, preparing young people not just for diplomas but for meaningful careers. That means investing in public schools and in partnerships with HBCUs, trade programs and businesses rooted right here.

Additionally, city services — from trash collection to pothole repair — must be reliable, transparent and equitable, regardless of zip code or income. Seamless governance is possible when everyone is at the table.

Yes, democracy works because people show up. Not just to vote once, but to attend city council meetings, serve on boards, hold leaders accountable and help shape decisions about where resources go.

This election isn’t just about who gets the title of mayor. It’s about whether Jackson gets another chance at becoming the capital city Mississippi deserves — a place that leads by example and doesn’t lag behind.

The successful Blue Origin mission didn’t happen by chance. It took coordinated effort, diverse expertise and belief in what was possible. The same is true for this city.

We are not launching into space. But we can launch a new era marked by cooperation over conflict, and by sustained civic action over short-term outrage.

On April 22, go vote. Vote not just for a person, but for a path forward because Jackson deserves liftoff. It starts with us.

Pauline Rogers is a longtime advocate for criminal justice reform and the founder of the RECH Foundation, an organization dedicated to supporting formerly incarcerated individuals as they reintegrate into society. She is a Transformative Justice Fellow through The OpEd Project Public Voices Fellowship.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1959, students marched for integrated schools

April 18, 1959

About 26,000 students took part in the Youth March for Integrated Schools in Washington, D.C. They heard speeches by Martin Luther King Jr., A. Phillip Randolph and NAACP leader Roy Wilkins.

In advance of the march, false accusations were made that Communists had infiltrated the group. In response, the civil rights leaders put out a statement: “The sponsors of the March have not invited Communists or communist organizations. Nor have they invited members of the Ku Klux Klan or the White Citizens’ Council. We do not want the participation of these groups, nor of individuals or other organizations holding similar views.”

After the march, a delegation of students went to present their demands to President Eisenhower, only to be told by his deputy assistant that “the president is just as anxious as they are to see an America where discrimination does not exist, where equality of opportunity is available to all.”

King praised the students, saying, “In your great movement to organize a march for integrated schools, you have awakened on hundreds of campuses throughout the land a new spirit of social inquiry to the benefit of all Americans.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days agoLawmakers used to fail passing a budget over policy disagreement. This year, they failed over childish bickering.

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days agoOn this day in 1873, La. courthouse scene of racial carnage

-

Local News7 days ago

Local News7 days agoAG Fitch and Children’s Advocacy Centers of Mississippi Announce Statewide Protocol for Child Abuse Response

-

Local News6 days ago

Local News6 days agoSouthern Miss Professor Inducted into U.S. Hydrographer Hall of Fame

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days agoFoley man wins Race to the Finish as Kyle Larson gets first win of 2025 Xfinity Series at Bristol

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoFederal appeals court upholds ruling against Alabama panhandling laws

-

Our Mississippi Home7 days ago

Our Mississippi Home7 days agoFood Chain Drama | Our Mississippi Home

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days agoHelene: Renewed focus on health of North Carolina streams | North Carolina