Mississippi Today

Mississippi would lose billions if Congress cuts Medicaid, report says

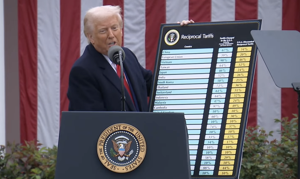

Mississippi will lose out on billions of dollars if Congress continues to advance legislation that would make deep cuts to Medicaid and other agencies to pay for a tax cut championed by President Donald Trump.

Tens of thousands of Mississippians could lose their health insurance as a result of what could be the largest cut in the history of Medicare and Medicaid.

While the budget resolution passed by Congress this week doesn’t specifically call for cuts to Medicaid, experts have said there is no way to achieve the proposed magnitude of cuts to a group of federal agencies – $880 billion – without slashing Medicaid.

Mississippi could see a potential reduction of up to $5.4 billion in federal funding for Medicaid under one proposal over the 10-year period, and $16 billion under another, according to a brief by the Center for Mississippi Health Policy based on a report conducted by the Hilltop Institute at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

Neither Gov. Tate Reeves, a Republican and outspoken supporter of Trump, nor the Mississippi Division of Medicaid responded to requests for comment by the time this story published.

All of Mississippi’s Republican Congress members – Reps. Mike Ezell, Trent Kelly and Michael Guest, along with Sens. Roger Wicker and Cindy-Hyde Smith – voted for the budget resolution. Rep. Bennie Thompson, a Democrat, voted no.

Mississippi, one of the poorest states in the nation with a large Medicaid population, would be significantly impacted by such a blow to the program. In particular, low-income people in vulnerable groups such as pregnant women, disabled adults, children and the elderly would face losing coverage, and hospitals and providers that rely on the program to reimburse for services could face massive losses.

One state lawmaker in recent weeks said it would bring Mississippi, one of the most federally dependent states in the nation, “to its knees” – particularly on the heels of the state Legislature passing an income tax cut that will result in an estimated loss of about $2.2 billion of the state’s $7 billion in operating revenue.

Medicaid is a federal-state program that provides health coverage to millions of people in the U.S. States administer the program, which is funded by both states and the federal government.

One option being discussed in Congress to downsize Medicaid is to lower the limit of or to eliminate what’s called the provider tax. Despite being a tax, it allows the state to draw down more federal dollars to use for the Medicaid program and to reimburse hospitals at a higher rate. Mississippi is currently nearly maxed out on the tax it’s allowed to impose on hospitals.

Health care leaders are sounding the alarm bells on the potential cuts, which they say will leave hospitals high and dry. The state, which has not expanded Medicaid, has had to rely in recent years on federal COVID-19 relief money and tweaks to its supplemental payments to keep hospitals afloat.

Richard Roberson, the CEO of the Mississippi Hospital Association, says that the provider tax is “a lifeline to Mississippi hospitals big and small.”

Now, it may be in jeopardy.

“If Congress reduces the 6% ceiling to 5%, 4%, 3% – whatever it may be – there are hundreds of millions of dollars at stake that would be lost that are right now keeping many Mississippi hospitals open,” Roberson said at a House Democratic Caucus meeting at the State Capitol last week. “So that’s a significant concern that we have.”

Other proposals being floated include capping the amount of money states can get per Medicaid enrollee, as well as reducing the federal match rate for states that have expanded Medicaid. As a state that hasn’t expanded Medicaid, Mississippi already does not receive an enhanced federal match rate, so it would not be affected by the latter option.

But any proposal that pushes people off Medicaid has direct consequences for hospitals, argued E.J. Kuiper, CEO of the Louisiana-based Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady Health System, which owns St. Dominic Health in Jackson.

Without insurance, patients let their health conditions deteriorate. That, in conjunction with the fact that the emergency room is the only place health care providers can’t turn patients away for not having money, means the emergency room becomes the only source of primary care for uninsured patients.

“Driving people off Medicaid rolls and making them uninsured – the societal cost is not going to go away,” Kuiper said. “People are still going to get sick whether they’re insured or not. What we’re concerned about is if people don’t have access to the Medicaid program, and are afraid to go see a doctor, what could be a $400 problem in April turns into a $10,000 problem in November.”

The emergency room is the most expensive place to receive care. When patients can’t pay, hospitals pick up the slack covering their care, and the practice – called uncompensated care – costs Mississippi hospitals millions each year.

Mississippi already has one of the highest rates of uninsured people in the nation.

Tens of thousands of Mississippians losing health insurance would have a domino effect on employment and the economy, according to a recent report from the Commonwealth Fund.

Mississippi – whose state leaders have called for work requirements for Medicaid enrollees and stress the importance of a strong labor force participation rate – faces nearly 10,000 people losing their jobs as the result of potential cuts to Medicaid.

The resolution narrowly passed Congress amid infighting between Republicans allied with Trump and hard-line conservatives who think the legislation doesn’t cut federal spending enough.

But now that the House and Senate have both passed identical versions of the budget resolution, lawmakers can begin working on specifics of what gets cut and how in a complicated process called “reconciliation.” Because reconciliation has been unlocked, Republicans can avoid a filibuster from Democrats and pass the final bill with a simple majority.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1873, La. courthouse scene of racial carnage

April 13, 1873

On Easter Sunday, after Reconstruction Republicans won the Louisiana governor’s race, a group of white Democrats vowed to “take back” the Grant Parish Courthouse from Republican leaders.

A group of more than 150 white men, including members of the Ku Klux Klan and the White League, attacked the courthouse with a cannon and rifles. The courthouse was defended by an all-Black state militia.

The death toll was staggering: Only three members of the White League died, but up to 150 Black men were killed. Of those, nearly half were killed in cold blood after they surrendered.

Historian Eric Foner called the Colfax Massacre “the bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era,” demonstrating “the lengths to which some opponents of Reconstruction would go to regain their accustomed authority.”

Congress castigated the violence as “deliberate, barbarous, cold-blooded murder.”

Although 97 members of the mob were accused, only nine went to trial. Federal prosecutors won convictions against three of the mob members, but the U.S. Supreme Court tossed out the convictions, helping to spell the end of Reconstruction in Louisiana.

A state historical marker said the event “marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South,” and until recent years, the only local monument to the tragedy, a 12-foot tall obelisk, honored the three white men who died “fighting for white supremacy.”

In 2023, Colfax leaders unveiled a black granite memorial that listed the 57 men confirmed killed and the 35 confirmed wounded, with the actual death toll presumed much higher.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Lawmakers used to fail passing a budget over policy disagreement. This year, they failed over childish bickering.

It is tough to determine the exact reason the Mississippi Legislature adjourned the 2025 session without a budget to fund state government, which will force lawmakers to return in special session to adopt a spending plan before the new fiscal year begins July 1.

In a nutshell, the breakdown seemed to have occurred when members of the Senate got angry at their House counterparts because they were not being nice to them. Or maybe vice versa.

Trying to suss this reasoning out is too difficult. The whole breakdown is confusing. It’s adolescent.

Perhaps there’s no point in trying to determine a reason. After all, when preteen children get mad at each other on the playground and start bickering, does it serve any purpose to ascertain who is right?

During a brief time early in the 2000s, when the state had the semblance of a true two-party system, the Legislature often had to extend the session or be called back in special session to finish work on the budget.

During those days, though, the Democrat-led House, the Republican-controlled Senate and the Republican governor were arguing about policy issues. There were often significant disagreements then over, say, how much money would be appropriated to the public schools or how Medicaid would be funded.

Now, with Republicans holding supermajorities over both the House and the Senate and a Republican in the Governor’s Mansion, the disagreements do not seem to rise to such legitimate policy levels.

It appears the necessity of a special session this summer is the result of House leaders not wanting to work on a weekend. And actually, that seemed like a reasonable request. It has always been a mystery why the Legislature could not impose earlier budget deadlines keeping lawmakers from having to work every year on a weekend near the end of the session.

But there were rumblings that if the House members did not want to work on the weekend, they should have been willing to begin budget negotiations with senators earlier in the session.

In fairness and to dig deeper, there also was speculation that the budget negotiations stalled because senators were angry that the House leadership was unwilling to work with them to fix mistakes in the Senate income tax bill. Instead of working to fix those mistakes in the landmark legislation, the House opted to send the error-riddled bill to the governor to be signed into law — because after all, the mistakes in the bill made it closer to the liking of the House leadership and Gov. Tate Reeves.

In addition, there was talk that House leaders were slowing budget negotiations by trying to leverage the Senate to pass a litany of bills ranging from allowing sports betting outside of casinos to increasing school vouchers to passing a traditional pet projects or “Christmas tree” bill.

The theory was that the House was mad that the Senate was balking on agreeing to pass the annual projects bill that spends state funds for a litany of local projects. For many legislators, particularly House members, their top priority each year is to bring funds home to their district for local projects, and not having a bill to do so was a dealbreaker for those rank-and-file House members.

To go another step further, some claimed senators were balking on the projects bill because of anger over the aforementioned tax bill. Another theory was that the Senate was fed up with House Ways and Means Chair Trey Lamar sneaking an inordinate number of projects in the massive bill for his home county of Tate.

But as stated earlier, does the reason for the legislative impasse really matter? The bottom line is that it appears that the reason for legislators not agreeing on a budget had nothing to do with the budget itself or disagreement over how much money to appropriate for vital state services.

House and Senate budget negotiators apparently did not even meet at the end of the session to fulfill the one task the Mississippi Constitution mandates the Legislature to fulfill: fund state government.

As a result, lawmakers will have to return to Jackson this summer in a costly special session not because of big policy issues, such as how to fund health care or how much money to plow into the public schools, but because “somebody done somebody wrong.”

Those big fights of previous years are less likely today because of the Republican Party grip on state government. The governor, the speaker and the lieutenant governor agree philosophically on most issues.

But in the democratic process, people who are like-minded can still have major disagreements that derail the legislative train — even if those disagreements are over something as simple as whether members are going to work during a weekend.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1864, Confederates kill up to 300 in massacre

The post On this day in 1864, Confederates kill up to 300 in massacre appeared first on mississippitoday.org

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days agoTariffs spark backlash in Virginia over economic impact | Virginia

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days agoVersailles asked to conserve water, county steps in to help

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed6 days agoNew Orleans police investigating hit-and-run crash in Seventh Ward; family says grandmother was hurt

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed5 days agoCrime scene shocks St. Tammany Trace residents as sheriff's investigation continues

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed4 days agoLocals react to Cara Spencer winning mayoral race

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days agoInvestigators continue search for Florida child missing since 2006

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed4 days agoProposal: Farm property tax break on solar from 80% to zero | North Carolina

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed4 days agoArkansas State Police launches new phone-free campaign