Mississippi Today

Mississippi to soon have its first state ‘climate action plan’

As of a year ago, about 30 states had a state-led initiative meant to help curb greenhouse gas emissions and avoid the worst-case, irreversible effects of global warming.

Mississippi, as much of the South, including Alabama, Tennessee, Texas and Georgia, does not have what’s called a “climate action plan.” Louisiana released its plan in 2022.

But soon, almost every state, including Mississippi, will have one thanks to recent financial incentives from the Environmental Protection Agency. As part of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, the EPA is giving states $3 million each to develop an initial climate action plan by March.

The plan has to include an inventory of greenhouse gas emissions, a list of measures to reduce emissions over the next five years, and an analysis of benefits for low-income and disadvantaged communities. Then, by 2025, states have to develop a comprehensive plan detailing specific projects as well as long-term goals for reducing emissions by 2050.

The EPA is making another $4.6 billion available for specific climate pollution projects through competitive grants, but states have to apply for those by April.

The Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality, which is in charge of submitting the state’s plan, is inviting the public to submit ideas and feedback through a new survey on its website.

MDEQ Executive Director Chris Wells told Mississippi Today that the $3 million planning grant will go a long way towards brainstorming and pitching future projects, but was critical of the EPA’s funding process.

“The process they’ve laid out is very odd and convoluted, I’ll just be very candid,” Wells said.

He called it a “head-scratcher” to have a deadline for the $4.6 billion a year before the state has come up with its comprehensive plan, and also so soon after submitting the much broader, initial climate action plan. Wells added, though, that MDEQ, in working with other agencies and the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, will still plan to submit what project ideas it has in hopes of getting some of the large pot of funding.

As far as the biggest greenhouse gas polluters, the director said they’re likely the same in Mississippi as elsewhere in the country: power generation and transportation.

“That’s not me casting shade on the power generation industry. It’s just that that’s a source of pollutants,” he said. “And then mobile sources. Particularly with all the economic activity going on, post COVID, things have ramped back up, and we’re back to pre-pandemic levels of traffic on the roads.”

The chart below shows a 2021 breakdown from the EPA of Mississippi’s pollution sources:

So far, MDEQ has a list of ideas for types of projects that could take shape with the state's new climate action plan: increasing solar capacity, electrification of trucks and school buses, using biofuel, energy efficiency upgrades through building codes, refrigerant replacement, appliance electrification, forest carbon management, agricultural best practices, and capturing and electrifying methane from landfill and wastewater.

But Wells emphasized that MDEQ, with its limited capacity and authority, would need outside support to enact large scale changes, like changing local building codes.

"A big need for us is beefing up our (electric vehicle) charging infrastructure," he said. "We're not in a position to unilaterally implement a project like that, so we have to other agencies, whether it's (the Mississippi Department of Transportation) or (the Mississippi Development Authority), and/or the private sector. I think the opportunity here for public-private partnerships is huge, because even if the government goes out and builds a charging station, someone's got to maintain it."

Wells said he hadn't had any conversations with any lawmakers to gauge their interest in supporting such projects.

While there's not a full inventory of Mississippi's greenhouse gas emitters, the EPA does track data on the top emitting facilities. Below is a map of some of the top polluters in Mississippi, which are largely comprised of power plants and chemical facilities:

In addition to taking MDEQ's survey, members of the public can e-mail project ideas to the agency at camp@mdeq.ms.gov. Wells said the agency will make the initial action plan due in March available to the public.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

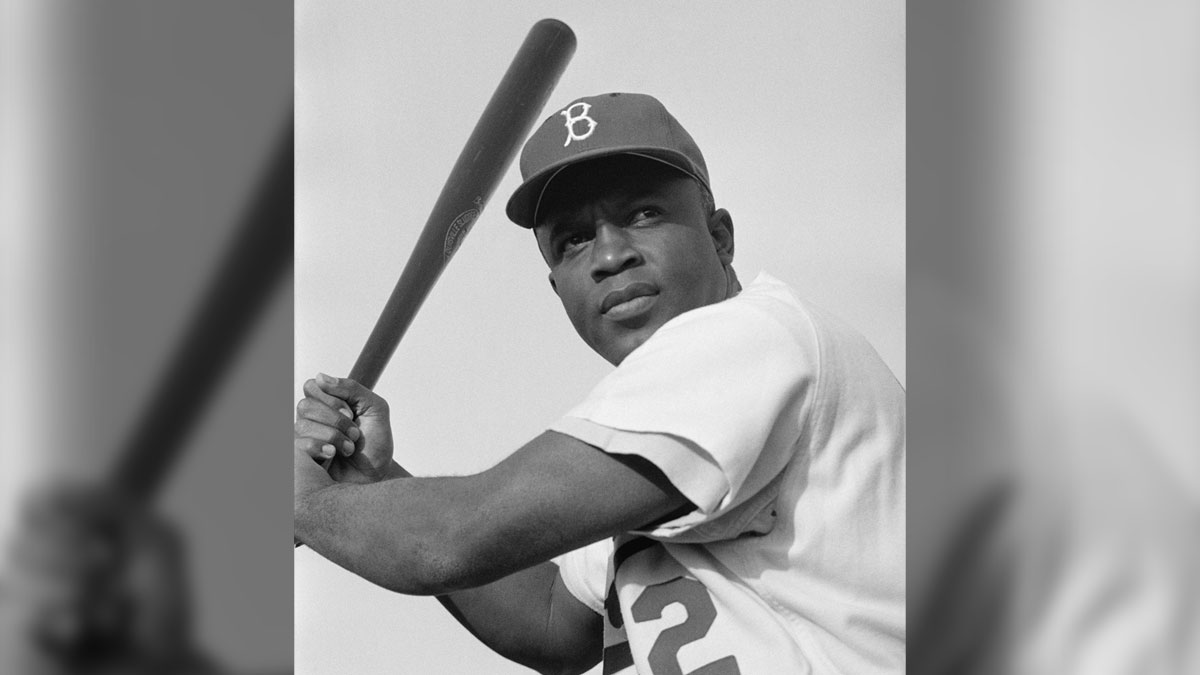

On this day in 1947, Jackie Robinson broke MLB color barrier

April 15, 1947

Jackie Robinson broke through the color barrier in Major League Baseball, becoming the first Black player in the 20th century.

Born in Cairo, Georgia, Robinson lettered in four sports at UCLA – football, basketball, baseball and track. After time in the military, he played for the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro Leagues. After his success there, Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey signed Robinson, and the legendary baseball player started for Montreal, where he integrated the International League.

In addition to his Hall of Fame career, he was active in the civil rights movement and became the first Black TV analyst in Major League Baseball and the first Black vice president of a major American corporation.

In recognition of his achievements, Robinson was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal.

Major League Baseball retired his number “42,” which became the title of the movie about his breakthrough.

Ken Burns’ four-hour documentary reveals that Robinson did more than just break the color barrier — he became a leader for equal rights for all Americans.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Mississippians highlight Black Maternal Health Week

Advocates and health care leaders joined lawmakers Monday morning at the Capitol to recognize Black Maternal Health Week, which started Friday.

The group was highlighting the racial disparities that persist in the delivery room, with Black women three times more likely to die of a pregnancy-related cause than white women.

“The bond between a mother and her baby is worth protecting,” said Cassandra Welchlin, executive director of the Mississippi Black Women’s Roundtable.

Rep. Timaka James-Jones, D-Belzoni, spoke about her niece Harmony, who suffered from preeclampsia and died on the side of the road in 2021 along with her unborn baby, three miles from the closest hospital in Yazoo City.

“It’s utterly important that stories are shared – but realize these are not just stories. This is real life,” she said.

The tragedy inspired James-Jones to become a lawmaker. She says she is working on gaining support to appropriate the funds needed to build a standalone emergency room in Belzoni.

But it isn’t just emergency medical care that’s lacking for some mothers. Mental health conditions are a leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths, defined as deaths up to one year postpartum from associated causes.

And more than 80% of pregnancy-related deaths are deemed preventable – making the issue ripe for policy change, advocates said.

“About 20 years ago, I was almost a statistic,” said Lauren Jones, a mother who founded Mom.Me, a nonprofit seeking to normalize the struggles of motherhood through community support. “I contemplated taking my life, I severely suffered from postpartum depression … None of my physicians told me that the head is connected to the body while pregnant.”

With studies showing “mounting disparities” in women’s health across the United States – and Mississippi scoring among the worst overall – more action is needed to halt and reverse the inequities, those at the press conference said.

The Mississippi Legislature passed four bills related to maternal health between 2018 and 2023, according to a study by researchers at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

“How many times are we going to have to come before committees like this to share the statistics before the statistics become a solution?” Jones asked.

A bill that would require health care providers to offer postpartum depression screenings to mothers is pending approval from the governor.

Rep. Zakiya Summers, D-Jackson, the organizer of the press conference, commended the Legislature for passing presumptive eligibility for pregnant women this year. The policy will allow women to receive health care covered by Medicaid as soon as they find out they are pregnant – even if their Medicaid application is still pending. It was spearheaded by Rep. Missy McGee, R-Hattiesburg.

Summers also thanked Rep. Kevin Felsher, R-Biloxi, for pushing paid parental leave for state employees through the finish line this year.

Speakers emphasized the importance of focusing Black Maternal Health Week not just on mitigating deaths but on celebrating one of life’s most vulnerable and meaningful events.

“Black Maternal Health Week is a celebration of life, since Black women don’t often get those opportunities to celebrate,” said Nakeitra Burse, executive director of Six Dimensions, a minority women-owned public health research agency. “We go into our labor and delivery and pregnancy with fear – of the unknown, fear of how we’ll be taken care of, and just overall uncertainty about the outcomes.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Trump to appoint two Northern District MS judges after Aycock takes senior status

President Donald Trump can now appoint two new judges to the federal bench in the Northern District of Mississippi.

U.S. District Judge Sharion Aycock announced recently that she was taking senior status effective April 15. This means she will still hear cases as a judge but will have a reduced caseload.

“I have been so fortunate during my entire legal career,” Aycock said in a statement. “As one of only a few women graduating in my law school class, I had the chance to break ground for the female practitioner.”

A native of Itawamba County, Aycock graduated from Tremont High School and Mississippi State University. She received her law degree from Mississippi College, where she graduated second in her class.

Throughout her legal career, she blazed many trails for women practicing law and female jurists. She began her career as a judge when she was elected as a Mississippi Circuit Court judge in northeast Mississippi in 2002, the first woman ever elected to that judicial district.

She held that position until President George W. Bush in 2007 appointed her to the federal bench. After the U.S. Senate unanimously confirmed her, she became the first woman confirmed to the federal judiciary in Mississippi.

This makes Aycock the second judge to take senior status in four years. U.S. District Judge Michael Mills announced in 2021 that he was taking senior status, but the U.S. Senate still has not confirmed someone to replace him.

President Joe Biden appointed state prosecutor Scott Colom to fill Mills’ vacancy in 2023. U.S. Sen. Roger Wicker approved Colom’s appointment, but U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith blocked his confirmation through a practice known as “blue slips,” where senators can block the confirmation of judicial appointees in their home state.

This means President Trump will now have the opportunity to appoint two federal judges to lifetime appointments to the Northern District. U.S. District Judge Debra Brown will soon be the only active federal judge serving in the district. Aycock, Mills, and U.S. District Judge Glen Davidson will all be senior-status judges.

Federal district judges provide crucial work to the federal courts through presiding over major criminal and civil trials and applying rulings from the U.S. Supreme Court and the U.S. Court of Appeals in the local districts.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days agoMeasles cases confirmed in Arkansas children after travel exposure

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days agoA self-proclaimed ‘loose electron’ journeys through Jackson’s political class

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoImpacts of Overdraft Fees | April 11, 2025 | News 19 at 10 p.m.

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days agoSleeping 14-year-old critically injured by bullet in Ferguson home; father flees scene

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days agoPilot Speaks on Helicopter Crash | April 10, 2025 | News 19 at 10 p.m.

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days ago1-on-1 with Gov. Kemp’s Senior Advisor | Full interview

-

Local News5 days ago

Local News5 days agoAG Fitch and Children’s Advocacy Centers of Mississippi Announce Statewide Protocol for Child Abuse Response

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days agoVoters can help maintain city of progress in upcoming Jackson election