DBenitostock/Moment via Getty Images

Kate Adamala, University of Minnesota

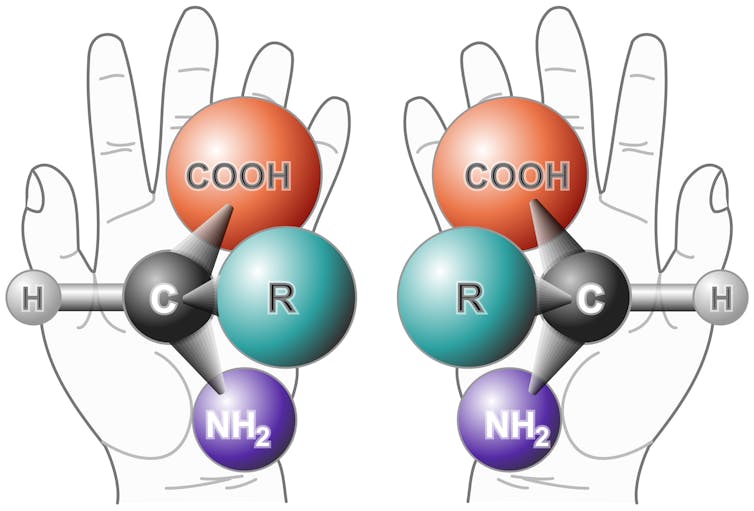

Most major biological molecules, including all proteins, DNA and RNA, point in one direction or another. In other words, they are chiral, or handed. Like how your left glove fits only your left hand and your right glove your right hand, chiral molecules can interact only with other molecules of compatible handedness.

Two chiralities are possible: left and right, formally called L for the Latin laevus and D for dexter. All life on Earth uses L proteins and D sugars. Even Archaea, a large group of microorganisms with unusual chemical compositions, stick to the program on the handedness of the main molecules they use.

For a long time, scientists have been speculating about making biopolymers that would mirror compounds in nature but in the opposite orientation – namely, compounds made of D proteins and L sugars. Recent years have seen some promising advancements, including enzymes that can make mirror RNAs and mirror DNAs.

NASA

When scientists observed that these mirror molecules behave just like their natural equivalents they considered that it would be possible to make a whole living cell from them. Mirror bacteria in particular had the potential to be a useful basic research tool – possibly allowing scientists to study a new tree of life for the first time and solve many problems in bioengineering and biomedicine.

This so-called mirror life – living cells made from building blocks with an opposite chirality to those that make up natural life – could have very similar properties to natural living cells. They could live in the same environment, compete for resources and behave like you would expect of any living organism. They would be able to evade infection from other predators and immune systems because these opponents wouldn’t be able to recognize them.

These features are why researchers like me were so attracted to mirror life in the first place. But these qualities are also huge bugs of this technology that make it a problem.

I am a synthetic biologist who studies using chemistry to create living cells. I am also a bioengineer who develops tools for the bioeconomy. As a chemist by training, engineering mirror life initially seemed like a fascinating way to answer foundational questions about biology and practically apply those findings to industry and medicine. As I learned more about the immunology and ecology of mirror life, however, I became aware of the potential environmental and health consequences of this technology.

Real concerns about hypothetical mirror life

It’s important to note that researchers are likely at least 10 to 30 years away from creating mirror bacteria. On the timescale of a fast-moving field like synthetic biology, a decade is a very long time. Creating synthetic cells is difficult on its own. Creating mirrored ones would require several technical breakthroughs.

However, it would come with a risk. If mirror cells were released into the environment, they would likely be able to quickly proliferate without much restriction. The natural mechanisms that keep ecosystems in balance, including infection and predation, would not work on mirror life.

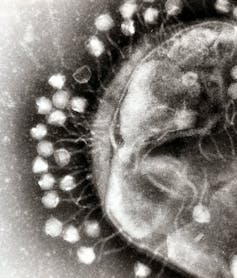

Bacteria, like most life forms, are susceptible to viral infections. These bacterial viruses, or bacteriophages, enter bacteria by binding to their surface receptors and then use their cellular machinery to replicate. But just as a left glove doesn’t fit a right hand, natural bacteriophages wouldn’t recognize mirror cell receptors or be able to use its machinery. Mirror life would likely be resistant to viruses.

Professor Graham Beards/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Microorganisms foraging in the environment also keep bacterial populations in check. They differentiate food from nonfood by using chemical “taste” receptors. Anything those receptors bind to, such as bacteria and organic debris, are considered edible, while things that cannot bind to those receptors, such as rocks, are classified as inedible. Think about how a dog foraging on the kitchen floor will eat a bread roll but only sniff a spoon and move on. Mirror life would be, to the bacterial predators, more like a spoon than bread – predators would “sniff” it with their receptors and move on because these cells can’t bind.

Safety from being eaten would be great news for mirror bacteria, because it would allow it to replicate freely. It would be much worse news to the rest of the ecosystem, because mirror bacteria might hog all the nutrients and spread uncontrollably. Even if mirror bacteria don’t actively attack other organisms, they would still consume food sources other organisms need. And since mirror cells would have much lower death rates than regular organisms due to a lack of predation, they would slowly but surely take over the environment.

Even if mirror cells grow more slowly than normal cells, they would be able to grow without anything stopping them.

Insufficient immunity

Another biological control mechanism that wouldn’t be able to “sniff” out mirror cells is the immune system.

Your immune cells constantly check everything they find in your blood. The decision tree of an immune cell is fairly simple. First, decide whether something is alive or not, then compare it with its database of “self” – your own cells. If it is alive but is not a part of you, then it needs to be killed. Mirror cells likely wouldn’t pass the first step of that screen: it would not induce an immune response because the immune system would not be able to recognize or bind to mirror cell antigens. This means mirror cells could infect an unprecedentedly wide variety of hosts.

You might think an infection from mirror bacteria could be treated with antibiotics of the same handedness. It would probably work, and may even be easier on your gut than regular antibiotic therapy. Because antibiotics are also handed, mirror versions of these drugs would not affect your gut microbiome, just like how regular antibioics would not affect mirror cells.

But humans are a relatively small part of the ecosystem. All other animals and plants may also be susceptible to infection from mirror pathogens. While it is possible to imagine developing mirror antibiotics to treat human infections, it is physically impossible to treat the entire plant and animal world. If all organisms are susceptible to even a slow-moving infection by mirror bacteria, there is no good treatment that could be deployed across the entire ecosystem.

Better safe than sorry

Mirror life is an exciting research subject and a potential tool with some practical applications in medicine and biotechnology. But for many scientists, including me, none of those benefits outweigh the serious consequences to human health and the environment that mirror life poses.

I and a group of researchers in immunology, ecology, biosafety and security – including some who used to actively work on mirror life – conducted a thorough analysis of possible concerns regarding the creation of mirror life. No matter how we looked at it, straight up or in the mirror, the conclusions were clear: The potential benefits of engineering mirror life are not worth the risk.

There is no way to make anything completely foolproof, and that includes any safeguards built into a mirror cell that could prevent the risk of accidental or deliberate release into the environment. Researchers working in this space, including us, may find this disappointing. But not making mirror cells can ensure the safety and security of the planet. More discussion among the global scientific community about what kinds of research on mirror biomolecules and related technologies are safe – as well as how to regulate this research – can help safeguard against potential harms.

Keeping mirror cells inside the mirror, rather than making them a physical reality, is the clearest path to staying safe.

Kate Adamala, Assistant Professor of Genetics, Cell Biology and Development, University of Minnesota

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.