Artur Plawgo/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Victor Ambros, UMass Chan Medical School

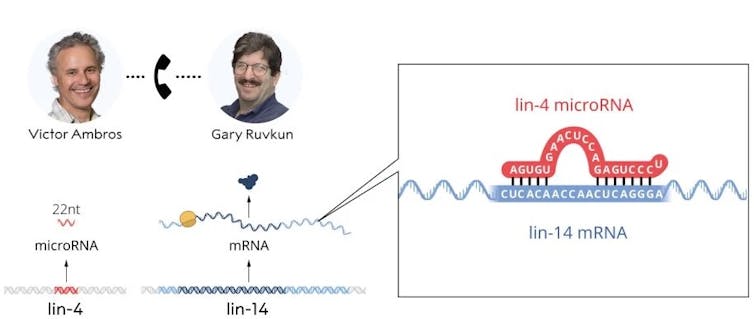

The 2024 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine goes to Victor Ambros and Gary Ruvkun for their discovery of microRNA, tiny biological molecules that tell the cells in your body what kind of cell to be by turning on and off certain genes.

The Conversation Weekly podcast caught up with Victor Ambros from his lab at the UMass Chan Medical School to learn more about the Nobel-winning research and what comes next. Below are edited excerpts from the podcast.

How did you start thinking about this fundamental question at the heart of the discovery of microRNA, about how cells get the instructions to do what they do?

The paper that described this discovery was published in 1993. In the late 1980s, we were working in the field of developmental biology, studying C. elegans as a model organism for animal development. We were using genetic approaches, where mutations that caused developmental abnormalities were then followed up to try to understand what the gene was that was mutated and what the gene product was.

It was well understood that proteins could mediate changes in gene expression as cells differentiate, divide.

We were not looking for the involvement of any sort of unexpected kind of molecular mechanisms. The fact that the microRNA was the product of this gene that was regulating this other gene in this context was a complete surprise.

There was no reason to postulate that there should be such regulators of gene expression. This is one of those examples where the expectations are that you’re going to find out about more complexity and nuance about mechanisms that we already know about.

But sometimes surprises emerge, and in fact, surprises emerge perhaps surprisingly often.

Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library via Getty Images

These C. elegans worms, nematodes, is there something about them that allows you to work with their genetic material more easily? Why are they so key to this type of science?

C. elegans was developed as an experimental organism that people could use easily to, first, identify mutants and then study the development.

It only has about a thousand cells, and all those cells can be seen easily through a microscope in the living animal. But still it has all the various parts that are important to all animals: intestine, skin, muscles, a brain, sensory systems and complex behavior. So it’s quite an amazing system to study developmental processes and mechanisms really on the level of individual cells and what those cells do as they divide and differentiate during development.

Listen to Victor Ambros on The Conversation Weekly podcast.

You were looking at this lin-4 gene. What was your surprising discovery that led to this Nobel Prize?

In our lab, Rosalind Lee and Rhonda Feinbaum were working on this project for several years. This is a very labor intensive process, trying to track down a gene.

And all we had to go by was a mutation to guide us as we gradually homed in on the DNA sequence that contained the gene. The surprises started to emerge when we found that the pieces of DNA that were sufficient to confer the function of this gene and rescue a mutant were really small, only 800 base pairs.

And so that suggested, well, the gene is small, so the product of this gene is going to be pretty small. And then Rosalind worked to pare down the sequence more and to mutate potential protein coding sequences in that little piece of DNA. By a process of elimination, she finally showed that there was no protein that could be expressed from this gene.

And at the same time, we identified this very, very small transcript of only 22 nucleotides. So I would say there was probably a period of a week or two there where these realizations came to the fore and we knew we had something new.

You mentioned Rosalind, she’s your wife.

Yeah, we’ve been together since 1976. And we started to work together in the mid-’80s. And so we’re still working together today.

And she was the first author on that paper.

That’s right. It’s hard to express how wonderful it is to receive such validation of this work that we did together. That is just priceless.

UMass Chan Medical School

Like it’s a Nobel Prize for her too?

Yes, every Nobel Prize has this obvious limitation of the number of people that they give it to. But, of course, behind that are the folks who worked in the lab – the teams that are actually behind the discoveries are surprisingly large sometimes. In this case, two people in my lab and several people in Gary Ruvkun’s lab.

In a way they’re really the heroes behind this. Our job – mine and Gary’s – is to stand in as representatives of this whole enterprise of science, which is so, so dependent upon teams, collaborations, brainstorming amongst multiple people, communications of ideas and crucial data, you know, all this is part of the process that underlies successful science.

That first week of the discoveries, did you anticipate at that point that this could be such a huge step for our understanding of genes?

Until other examples are found of something new, it’s very hard to know how peculiar that particular phenomenon might be.

We’re always mindful that evolution is amazingly innovative. And so it could have been that this particular small RNA base-pairing to this mRNA of lin-14 gene and turning off production of the protein from lin-14 messenger RNA, that could be a peculiar evolutionary innovation.

The second microRNA was identified in Gary Ruvkun’s lab in 1999, so it was a good six years before the second one was found, also in C. elegans. Really, the watershed discovery was when Ruvkun showed that let-7, the other microRNA, was actually conserved perfectly in sequence amongst all the bilaterian animals. So that meant that let-7 microRNA had been around for, what, 500 million years?

And so it was immediately obvious to the field that there had to be other microRNAs – this was not just a C. elegans thing. There must be others, and that quickly emerged to be the case.

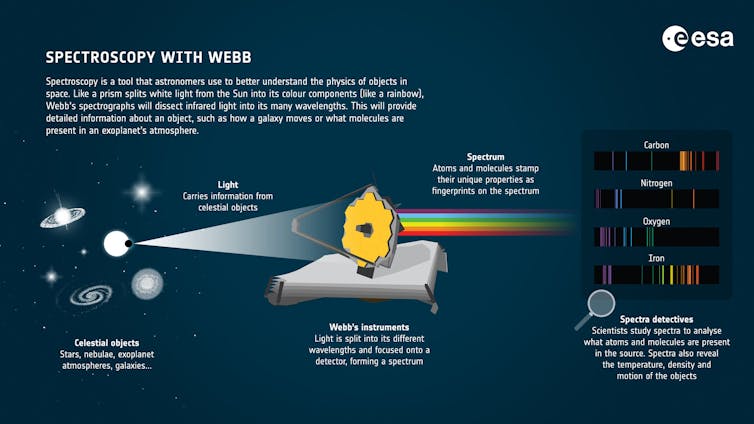

© The Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine. Ill. Mattias Karlén

You and Gary Ruvkun had been postdoctoral fellows at the same time at MIT, but by the time you made your respective discoveries, you’d both set up your own labs. Would you call them rival labs, in the same town?

No, I would certainly not call it rival labs. We were working together as postdocs basically on this problem of developmental timing in Bob Horvitz’s lab.

We just basically informally divided up the work. The understanding was, OK, Ambros lab will focus on lin-4 gene, and Ruvkun lab will focus on lin-14, and we anticipated that there would be a point that we would get together and share information about what we’ve learned and see if we could come to a synthesis.

That was the informal plan. It was not really a collaboration. It was certainly not a rivalry. The expectation was that we would divide up the work and then communicate when the time came. There was an expectation in this community of C. elegans researchers that you should share data freely.

Your lab still works on microRNA. What are you investigating? What questions do you still have?

One I find very interesting is a project where we collaborated with a clinician, a geneticist who studies intellectual disability. She had discovered that her patients, children with intellectual disabilities, in certain families carried a mutation that neither of their parents had – a spontaneous mutation – in the protein that is associated with microRNAs in humans called the Argonaute protein.

Each of our genomes contains four genes for Argonautes that are the partners of microRNAs. In fact, this is the effector protein that is guided by the microRNA to its target messenger RNAs. This Argonaute is what carries out the regulatory processes that happen once it finds its target.

These so-called Argonaute syndromes were discovered, where there are mutations in Argonautes, point mutations where only one amino acid changes to another amino acid. They have this very profound and extensive effect on the development of the individual.

And so working with these geneticists, our lab and other labs took those mutations, that were essentially gifted to us by the patient. And then we put those mutations into our system, in our case into C. elegans‘ Argonaute.

I’m excited by the very organized, active partnership between the Argonaute Alliance of families with Argonaute syndromes and the basic scientists studying Argonaute.

How does this collaboration potentially help those patients?

What we’ve learned is that the mutant protein is sort of a rogue Argonaute. It’s basically screwing up the normal process that these four Argonautes usually do in the body. And so this rogue Argonaute, in principle, could be removed from the system by trying to employ some of the technology that folks are developing for gene knockout or RNA interference of genes.

This is promising, and I’m hopeful that the payoff for the patients will come in the years ahead.![]()

Victor Ambros, Professor of Molecular Medicine, UMass Chan Medical School

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.