Mississippi Today

Marine’s troubled life set to end with execution

Marine’s troubled life set to end with execution

Editor’s note: This story contains references to suicide. If you or someone you know may be considering suicide, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or dial 988. Local resources include the Mississippi Department of Mental Health DMH Helpline at 1-877-210-8513.

Today’s scheduled execution of Thomas Loden Jr. may bring some closure to his victim’s family but also, barring any last-minute stays, end to a troubled life.

While no justification can be made for Loden’s assault and murder of a 16-year-old waitress, what brought him to that point may be found in his past.

In court documents, attorneys for Loden have told the story of a man who was physically and sexually abused as a child and experienced post-traumatic stress disorder from his military deployment.

The 58-year-old has been on death row for over 20 years for the 2000 murder and rape of Leesa Gray in Dorsey in Itawamba County.

He had no criminal record prior to Gray’s murder, his attorneys said.

Loden was born to a mother who married his father at age 17 to escape a difficult home life, according to court documents.

His father was physically and sexually abusive toward his mother, and it is likely Loden witnessed the abuse, court documents say.

His parents divorced when he was a toddler, and Loden bounced between living with his parents. Court documents say his step parents physically abused him.

Loden also experienced sexual abuse from a church staff member at Bible school.

As a result of trauma, he had attempted suicide several times and had substance use problems, according to court documents.

Loden gained stability when he went to live with his grandparents on their farm in Itawamba County, according to court documents.

After graduating from Itawamba Agricultural High School in 1982, Loden joined the Marine Corps.

His commanding officer described Loden as “a poster Marine” and the “hardest charging Marine I have ever had work for me,” according to court documents.

He sought promotion opportunities, eventually reaching the rank of gunnery sergeant. Throughout his career, he received several awards and medals such as the Combat Action Ribbon, Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal and the Good Conduct Medal, according to court documents.

Loden served in the Gulf War where his unit was often attacked. He witnessed deaths, including that of a close friend.

That friend’s death experience changed him, Loden’s wife said in court documents, and she said he was different after the war. He drank heavily, took drugs, had nightmares and flashbacks and picked fights. He became less social, distant from loved ones and felt anxious in crowds.

A psychologist who worked with Loden’s attorneys diagnosed him with chronic PTSD from combat, complex PTSD from his childhood and borderline personality disorder.

After deployment, Loden was transferred a number of times, including in 1995 to Virginia to be an instructor for the Marine Corps’ Anti-Terrorism Security Team – a prestigious and high pressure assignment.

In Virginia, he met his third wife. His two previous marriages ended when his wives were unfaithful, according to court documents. He had a daughter with his third wife, and the family moved to Vicksburg for him to work as a recruiter.

His third marriage also turned out to be troubled.

Loden’s attorneys argued their strained relationship, paired with drugs and alcohol, influenced how he acted the night of Gray’s death.

Days before the murder, Loden traveled from Vicksburg to his grandparent’s farm to care for his grandmother. He was also stressed from the recruiting quotas at work, according to court documents.

He had been drinking and took drugs throughout the day when he received a call from his wife, who claimed she had telephone sex with a partner from the law firm where she worked, and that she planned to have sex with him while Loden was away, according to court documents.

That evening he went to Comer’s Restaurant where Gray was his waitress and tried to flirt with the teenager. Loden waited until she was off work and found her parked by the side of the road with a flat tire.

He offered help and told her he was with the Marines. He asked if she ever thought about joining, and Gray gave a response that angered him, according to court documents. Loden forced her into his van, where he repeatedly raped and murdered her.

The psychologist said Loden experienced a localized episode of dissociative amnesia when he killed Gray, according to court documents.

When her body was discovered in his car, law enforcement found Loden lying by the side of the road with self-inflicted wounds on his wrists and the words “I’m sorry” carved into his chest, according to court documents.

During his 2001 trial, Loden admitted to killing Gray, as opposed to letting her go, because it would “tarnish [his] image as the perfect Marine.” In later appeals, mitigation evidence became a focus of his attorneys’ argument that Loden had ineffective assistance of counsel.

Loden pleaded guilty to all counts and waived his right to a jury for trial and sentencing, hoping to spare Gray’s family and friends a long trial.

“I hope you may have some sense of justice when you leave here today,” he said during his trial.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

‘Trainwreck on the horizon’: The costly pains of Mississippi’s small water and sewer systems

This is the first of a two-part story.

“This state ain’t nothing but a big Jackson,” Central District Public Service Commissioner De’Keither Stamps said during a December meeting that harkened back to his time as a capital city councilman. “We got a whole statewide trainwreck that’s on the horizon.”

Over a thousand drinking water systems, most of them small, and hundreds of additional sewer systems operate in Mississippi. Nearly 60 percent of those water systems, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, have committed a violation in the last three years, and one in three sewer systems in the state have violated pollution limits in just the last year.

In 2014, a couple in DeSoto County, the wealthiest part of the state, sent a letter with photos of their yard to the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality. Tarnishing their garden were small clumps of feces and wads of wet toilet paper stuck together.

“When having company with children playing in our backyard last summer, suddenly, water and sewage began rushing out of the back flow valve, into the flower bed, across our yard and into the backyard where the children were playing,” the Olive Branch couple wrote. “Everyone had to come inside due to the sewage rushing in our yard…This went on for several hours.”

The culprit, MDEQ later identified, was the malfunctioning collection system at the Belmor Lakes Subdivision sewage treatment facility, which serves about 200 people. The couple continued sending complaints the next four years, while the state sent repeated notices of violation to the plant’s operator. The facility allowed sewage overflows from at least 2011 to 2020, records show, and it remains out of compliance to this day.

Another facility, at the Openwood Plantation in Vicksburg, exceeded fecal coliform limits as early as 2004. A 2011 inspection noted the plant’s effluent structure “has been leaking for at least two years, still not repaired.” The next year, a neighbor complained to MDEQ about a funky smelling green liquid on their property. The agency found not only was the treatment plant responsible, but it also leaked raw sewage that flowed into a local recreational lake. Over two decades after the initial violation, the facility still regularly exceeds, by significant degrees, water pollution limits for chemicals such as E.coli, chlorine and ammonia nitrogen.

Small water and sewer systems around Mississippi have for years struggled to stay afloat because of, to some degree, the nature of being a small water or sewer system. Now, as they try to correct deficiencies during a time of growing regulations and higher costs, many cash-strapped systems are facing the hard reality of needing to raise rates for necessary services in the country’s second poorest state.

“System officials think that part of the job is to hold rates at a low level, and that doesn’t necessarily jive with what the need is,” said Bill Moody, director of the Bureau of Water Supply at the Mississippi State Department of Health.

Moody spoke anecdotally of system owners who bragged about keeping rates low, unaware of the revenue shortfall they would soon have.

A 2023 EPA report on funding needs for drinking water systems found that, over the next 20 years, Mississippi will have an $8.1 billion need. That equals $2,751 per Mississippian, the fourth largest per capita need of any state. Small systems in the state had a per capita need 26% higher than that, the report’s data shows, equalling $3,456 per person.

The United States, and especially Mississippi, suffers from what industry wonks call “fragmentation.” Compared to other countries, the U.S. has a spread out population, meaning its utilities are spread out, too. But by having so many water and sewer systems serving small pockets of people, scant infrastructure funding is spread to the point it loses spending power.

“ The problems the city of Jackson has had, for instance, is replayed over and over and over again in these smaller systems,” said MDEQ executive director Chris Wells. “ What you have is these small systems that, for one reason or other, aren’t properly functioning.”

For instance, Wells explained, a developer with no utility experience might build and operate a sewage lagoon to serve a subdivision. Sometimes the developer moves or dies and passes the reins onto the homeowners association.

“We’ve had situations where the person who built the lagoon or the treatment system literally disappears, abandons the system,” Wells said.

While consolidating small systems would help, experts say, some are so far behind that their customers’ bills will go up regardless.

!function(){“use strict”;window.addEventListener(“message”,(function(a){if(void 0!==a.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var e=document.querySelectorAll(“iframe”);for(var t in a.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var r,i=0;r=e[i];i++)if(r.contentWindow===a.source){var d=a.data[“datawrapper-height”][t]+”px”;r.style.height=d}}}))}();

“It gets a little depressing, I don’t know what the answer is,” Greg Pierce, a water policy expert at the University of California, Los Angeles said. “Usually these systems are under-maintained. They have low rates, but they also have low quality and low reliability.”

Each year, the Health Department takes the temperature of the state’s drinking water systems. In the last two years, the agency found 83 providers that were in “poor” condition. While the median population for a water system in Mississippi is around 1,400 people, that number drops to 422 for the “poor” performing systems, about 80% of which serve under a 1,000 people.

In the small town of Utica, for instance, the Reedtown Water Association has frequent power outages and boil water notices. Stamps, the Public Service commissioner for the area, said necessary repairs would cost $4 million to $5 million, “an amount far beyond what the water association and its (1,200) customers can afford.”

One water association with just 829 customers – Cascillia, in Tallahatchie County – had 83 violations in just the last 5 years, including exceeding arsenic limits in 2023. Several other small water systems (such as the Moore Bayou Water Association in Coahoma County, or Truelight Redevelopment in Sharkey County) are considered “serious violators” by the EPA for, in part, not meeting limits on disinfectant byproducts that were set in 2006. Of the state’s 19 “serious violators,” more than half serve 1,200 or fewer people. The EPA defines a small water system as serving 3,300 people or fewer.

Smaller systems struggle nationwide. A 2018 study from researchers at the University of California, Irvine and Columbia University found that systems in rural areas around the country see “substantially” more violations than those in urban areas.

Wells, of MDEQ – which oversees sewer compliance – said it’s a challenge motivating struggling systems to meet permit limits. The state can technically take over a system, but MDEQ doesn’t have the resources to do so, and levying large fines can be counterproductive because ratepayers ultimately have to make up the difference.

“Every dollar that we take in penalties is one less dollar that the community has to spend toward the upgrades that they need to make,” he said.

Wells described that, for some repeat offenders, sending them violation notices is like “trying to get blood out of a turnip.” While MDEQ works with systems to correct deficiencies, he said, sometimes the best answer is a third-party utility coming in to save the day.

The American Society of Civil Engineers’ 2024 “Infrastructure Report Card” estimated that Mississippi, between all its water and sewer systems, needed $9.4 billion in investments over the next 20 years.

“The capacity of drinking water systems in the state is mediocre,” the report says, adding that “wet weather conditions, inconsistent maintenance, and a lack of rehabilitation pose extreme threats to the state’s wastewater infrastructure.”

Between the historic amounts of federal funding from the American Rescue Plan Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Mississippi received roughly $1.2 billion for water and wastewater improvements, or just 13% of the state’s projected need.

Especially with large expenses looming to meet the new national standards for PFAs, some small systems are looking to consolidate to ease financial headaches. The Oxford Eagle reported last year, for instance, that the Punkin Water Association would soon join the city of Oxford’s service area after years of water quality issues.

But given the spacial challenges of connecting far apart systems – especially in Mississippi, which, according to Census data, has the fourth most rural population of any state – some say there are limits to how much water providers can actually unify.

“When it comes to the physical pipes in the ground, you can’t move them,” said Mildred Warner, a professor of city and regional planning at Cornell University, explaining that many systems can only consolidate in terms of management.

Mississippi is experimenting with consolidating management for some of its small, privately owned water and sewer systems. In 2021, a company called Great River began buying struggling systems around the state. A subsidiary of the national firm Central States Water Resources, the company focuses on struggling, poorly financed systems that most large utility firms wouldn’t touch. Now operating in 11 states, the company has access to more resources than what a small operator would, and can reduce overall costs by spreading them out throughout its service area.

In Mississippi, part of the PSC’s job is to make sure private utilities that have a monopoly over a given service area, like Great River, only charge customers for what their services are worth, plus enough profit to stay in business. Given the challenges of some small systems in the state, the PSC welcomed the company’s help. But Great River, as is common when a large private utility takes over, quickly imposed steep rate increases to fund its repairs.

As Great River’s ratepayers plead with the PSC to soften the financial blow, the condition of some Mississippi water and sewer providers suggest those basic services will have to cost much more than they used to, especially for customers of small systems.

Part two of this story will further explore the Great River’s impact on ratepayers, and what the future holds for small water and sewer systems struggling to stay afloat.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

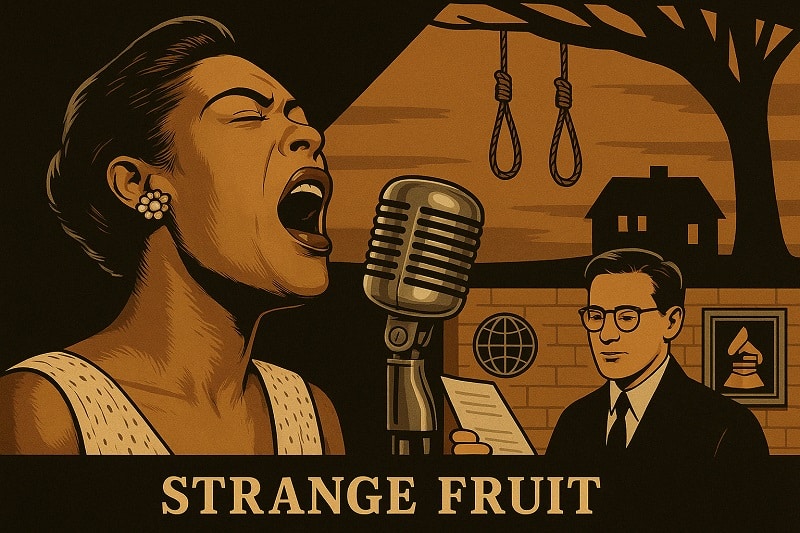

On this day in 1939, Billie Holiday recorded ‘Strange Fruit’

April 20, 1939

Legendary jazz singer Billie Holiday stepped into a Fifth Avenue studio and recorded “Strange Fruit,” a song written by Jewish civil rights activist Abel Meeropol, a high school English teacher upset about the lynchings of Black Americans — more than 6,400 between 1865 and 1950.

Meeropol and his wife had adopted the sons of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were orphaned after their parents’ executions for espionage.

Holiday was drawn to the song, which reminded her of her father, who died when a hospital refused to treat him because he was Black. Weeks earlier, she had sung it for the first time at the Café Society in New York City. When she finished, she didn’t hear a sound.

“Then a lone person began to clap nervously,” she wrote in her memoir. “Then suddenly everybody was clapping.”

The song sold more than a million copies, and jazz writer Leonard Feather called it “the first significant protest in words and music, the first unmuted cry against racism.”

After her 1959 death, both she and the song went into the Grammy Hall of Fame, Time magazine called “Strange Fruit” the song of the century, and the British music publication Q included it among “10 songs that actually changed the world.”

David Margolick traces the tune’s journey through history in his book, “Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday and the Biography of a Song.” Andra Day won a Golden Globe for her portrayal of Holiday in the film, “The United States vs. Billie Holiday.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Mississippians are asked to vote more often than people in most other states

Not long after many Mississippi families celebrate Easter, they will be returning to the polls to vote in municipal party runoff elections.

The party runoff is April 22.

A year does not pass when there is not a significant election in the state. Mississippians have the opportunity to go to the polls more than voters in most — if not all — states.

In Mississippi, do not worry if your candidate loses because odds are it will not be long before you get to pick another candidate and vote in another election.

Mississippians go to the polls so much because it is one of only five states nationwide where the elections for governor and other statewide and local offices are held in odd years. In Mississippi, Kentucky and Louisiana, the election for governor and other statewide posts are held the year after the federal midterm elections. For those who might be confused by all the election lingo, the federal midterms are the elections held two years after the presidential election. All 435 members of the U.S. House and one-third of the membership of the U.S. Senate are up for election during every midterm. In Mississippi, there also are important judicial elections that coincide with the federal midterms.

Then the following year after the midterms, Mississippians are asked to go back to the polls to elect a governor, the seven other statewide offices and various other local and district posts.

Two states — Virginia and New Jersey — are electing governors and other state and local officials this year, the year after the presidential election.

The elections in New Jersey and Virginia are normally viewed as a bellwether of how the incumbent president is doing since they are the first statewide elections after the presidential election that was held the previous year. The elections in Virginia and New Jersey, for example, were viewed as a bad omen in 2021 for then-President Joe Biden and the Democrats since the Republican in the swing state of Virginia won the Governor’s Mansion and the Democrats won a closer-than-expected election for governor in the blue state of New Jersey.

With the exception of Mississippi, Louisiana, Kentucky, Virginia and New Jersey, all other states elect most of their state officials such as governor, legislators and local officials during even years — either to coincide with the federal midterms or the presidential elections.

And in Mississippi, to ensure that the democratic process is never too far out of sight and mind, most of the state’s roughly 300 municipalities hold elections in the other odd year of the four-year election cycle — this year.

The municipal election impacts many though not all Mississippians. Country dwellers will have no reason to go to the polls this year except for a few special elections. But in most Mississippi municipalities, the offices for mayor and city council/board of aldermen are up for election this year.

Jackson, the state’s largest and capital city, has perhaps the most high profile runoff election in which state Sen. John Horhn is challenging incumbent Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba in the Democratic primary.

Mississippi has been electing its governors in odd years for a long time. The 1890 Mississippi Constitution set the election for governor for 1895 and “every four years thereafter.”

There is an argument that the constant elections in Mississippi wears out voters, creating apathy resulting in lower voter turnout compared to some other states.

Turnout in presidential elections is normally lower in Mississippi than the nation as a whole. In 2024, despite the strong support for Republican Donald Trump in the state, 57.5% of registered voters went to the polls in Mississippi compared to the national average of 64%, according to the United States Elections Project.

In addition, Mississippi Today political reporter Taylor Vance theorizes that the odd year elections for state and local officials prolonged the political control for Mississippi Democrats. By 1948, Mississippians had started to vote for a candidate other than the Democrat for president. Mississippians began to vote for other candidates — first third party candidates and then Republicans — because of the national Democratic Party’s support of civil rights.

But because state elections were in odd years, it was easier for Mississippi Democrats to distance themselves from the national Democrats who were not on the ballot and win in state and local races.

In the modern Mississippi political environment, though, Republicans win most years — odd or even, state or federal elections. But Democrats will fare better this year in municipal elections than they do in most other contests in Mississippi, where the elections come fast and often.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoFoley man wins Race to the Finish as Kyle Larson gets first win of 2025 Xfinity Series at Bristol

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days agoFederal appeals court upholds ruling against Alabama panhandling laws

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days agoFDA warns about fake Ozempic, how to spot it

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed3 days agoDrivers brace for upcoming I-70 construction, slowdowns

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed5 days agoLieutenant governor race heats up with early fundraising surge | Virginia

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days agoWall Street poised to add to last week’s gains when markets open Monday

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days agoAbandoned property causing issues in Pine Lawn, neighbor demands action

-

Mississippi Today4 days ago

Mississippi Today4 days agoSee how much your Mississippi school district stands to lose in Trump’s federal funding freeze