Mississippi Today

Jailed for their own safety, 14 Mississippians died awaiting mental health treatment

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Mississippi Today. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Butch Scipper is haunted by the deaths of three men.

As chancery clerk of Quitman County in the Mississippi Delta, he coordinates a legal process in which people are ordered into treatment for serious mental illness or substance abuse — a common way for Mississippians, especially poor people without insurance, to access inpatient care.

Dozens of times a year, people ask Scipper for help because they are afraid sick family members will hurt themselves or others. Up until a few years ago, he sent many of those family members to jail as they waited to be evaluated and treated.

Jailing people with no criminal charges during the civil commitment process is common in Mississippi because many county officials see no other option when publicly funded mental health facilities are unavailable. In jail, Scipper figured, people going through the commitment process would be prevented from harming themselves or others.

Yet three men — Tyrone Compton, Brandon Raymond and Brian Sneed — killed themselves in the Quitman County jail. Compton and Raymond died the same way, in the same cell, just seven months apart in 2006 and 2007. Sneed died in 2019.

“These three guys run back and forth across my head,” Scipper said. Sending them to jail, he now believes, “was not the right thing to do.”

Since 2006, at least 14 Mississippians have died after being placed in jail during the civil commitment process, purportedly for their own safety. Nine of them, including those three men, died by suicide. Twelve had not been charged with a crime.

It’s not easy to know what goes on inside Mississippi jails — unlike in many states, they’re not subject to mandatory health and safety standards — but lawsuits and Mississippi Bureau of Investigation reports provide some visibility.

Mississippi Today and ProPublica read sworn testimony by family members, jail staffers, administrators, sheriffs and other inmates regarding deaths in jail during the commitment process. We reviewed medical and jail records. We compared suicide prevention policies to nationally recognized guidelines. And we shared key facts about these cases or the policies in effect at the time with a dozen experts in correctional health care, including psychiatrists and other physicians.

Before 11 of the deaths, the medical care and suicide prevention measures fell short of national standards, sometimes shockingly so, according to experts and a review of those standards. (The care provided before the other three deaths, including the most recent one in August, is unclear.)

Before most of the nine suicides, staff didn’t take some basic steps to prevent people from killing themselves, according to those experts and nationally accepted guidelines. And when people going through the commitment process exhibited serious medical issues, jail staff didn’t get them the help they needed, experts said after reviewing the circumstances of those deaths drawn from a Mississippi Bureau of Investigation report, depositions and records filed in court. Staff didn’t review medical histories. They interpreted signs of medical distress as manifestations of mental illness or the influence of drugs or alcohol. They failed to act.

“When you see somebody that ain’t eating, you can’t just let them sit there and do that. … They’re still somebody. They’re still a human being.”

Terry Fox, husband of Nakema Fox, who died of a pulmonary embolism in jail

Local officials in Mississippi say they sometimes need to jail people during the commitment process to keep them safe. But according to the experts we interviewed, jails not only fail to guarantee safety for people with serious mental illness, they can be particularly dangerous for them.

“There’s a whole lot more to safety than just bars and shackles,” said Dr. Robert Greifinger, the former chief medical officer for the New York state prison system.

That point has long been made by sheriffs and jail administrators in Mississippi, too. In 1999, for instance, a 43-year-old man killed himself in the Union County jail as he waited to be taken to Mississippi State Hospital near Jackson for psychiatric treatment.

“He was under watch, but you can’t watch him every minute,” Joe Bryant, then sheriff of the north Mississippi county, said at the time. “It just brings to light a problem that county jails face: There should be some means besides a county jail to house mental patients. A jail is not equipped for this.”

Nearly a quarter-century later, the problem persists. A law passed in 2009 requiring jails to meet state standards if they hold people awaiting psychiatric treatment has resulted in just one jail that’s certified among the 71 that detained about 800 such people in the year ending in June 2023.

When someone dies in jail awaiting treatment, litigation is the primary way families can try to hold officials accountable. Yet none of the nine lawsuits filed over deaths since 2006 have resulted in a court ruling that held county or jail officials responsible. Four were settled. One is ongoing. The rest were dismissed or lost at trial.

Legal experts say such suits rarely succeed, in part because it’s so hard to prove that jail medical care was so bad that it violated someone’s constitutional rights.

But the failure to meet a legal standard doesn’t mean there isn’t a problem. Correctional health care experts said Mississippi’s practice of jailing people solely because they’re mentally ill or addicted to drugs or alcohol has caused deaths that could have been prevented.

“It’s taking people with a suspected health problem and putting them in a place that is likely going to increase their risk of dying from that health problem. The health risks of jail are well established, and they include suicide,” said Dr. Homer Venters, former chief medical officer of New York City jails.

“It’s a terrifying practice.”

Unwatched and Unprotected

After Scipper took office as Quitman County chancery clerk in 1992, he started handling up to 100 civil commitments a year. He instructed family members on how to file the paperwork, waited for judges to order people into treatment and, if families didn’t want them at home, figured out where to hold them in the meantime. “We used to just automatically put them in the jailhouse,” he said.

In 2006, a man came to Scipper’s office to file commitment papers after his son attacked him. The father was concerned the young man, Tyrone Compton, would hurt himself. Later that day, Compton hanged himself from a set of bars mounted in front of a window in his cell.

Seven months later, Brandon Raymond hanged himself from the same bars as he waited to be taken to a state hospital for drug rehab. It wasn’t until after his death that a piece of metal was welded onto the bars, even though the jail administrator had warned county officials about the danger after the first suicide, according to a deposition in a lawsuit filed over Raymond’s death.

It was an obvious shortcoming. For years, suicide was the leading cause of death in U.S. jails, primarily from hanging. Long-accepted standards direct jail staff to keep people who are at risk of suicide away from bars or protrusions.

A review of court filings and investigations related to the suicides points to shortcomings in how people going through the commitment process were screened for suicide risk, where they were held and how they were monitored.

Suicide prevention policies that address these issues have long been recognized as an essential element of jail medical care. But the former Quitman County jail administrator testified that he didn’t know about any policies whatsoever at the time of Compton and Raymond’s deaths.

David Fathi, an attorney who has worked on litigation over jail and prison conditions for more than 25 years and now serves as director of the ACLU’s National Prison Project, reviewed suicide prevention policies that were in effect at five Mississippi jails where several people died by suicide. Some, he said, were “among the worst policies I’ve ever seen.” One policy said staff could turn off water in a cell to reduce the risk of self-harm — a practice Fathi said has resulted in deaths by dehydration of people with mental illness.

“To send people to jail because they have mental illness, and to send them to a jail that has either flagrantly inadequate suicide policies or no suicide policy at all, is a recipe for disaster,” Fathi said.

If you or someone you know needs help:

- Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988

- Text the Crisis Text Line from anywhere in the U.S. to reach a crisis counselor: 741741

Screening inmates for suicide risk is a key part of such policies, and it’s a standard part of the booking process at jails across the country. Staff should ask inmates multiple questions, ranging from explicit ones about whether they have considered suicide to less direct ones like “Have you ever wished you were dead or wished you could go to sleep and not wake up?”

At least six of the nine people who killed themselves, including Compton and Raymond, weren’t screened at all or underwent screenings that didn’t meet national standards, according to depositions and jail records.

For nearly three years after Raymond died without being screened, staff still did not conduct screenings for medical or psychiatric issues, according to depositions. Jail policy had required such screenings for years, but employees, including the former jail administrator, didn’t know that, according to depositions.

Quitman County’s current medical questionnaire does ask staff to determine whether the inmate is “so disoriented or mentally confused as to suggest the risk of suicide,” but leaders in correctional health care told Mississippi Today and ProPublica that’s not sufficient.

“I can still see Brandon in my yard. I can still see Brandon coming in my front door. I’ve lost my daddy, and I’ve lost my mama, but it’s nothing like my baby.”

Sandra Pruitt, mother of Brandon Raymond, in a deposition

Compton’s father and Raymond’s mother filed lawsuits against Quitman County, the sheriff and sheriff’s department staff. In response to the Compton lawsuit, the defendants argued they were shielded by qualified immunity, a doctrine that protects government officials from liability for violations of constitutional rights that are not clearly established. They also argued that Compton’s death was the result of his own conduct and that even if his rights had been violated, it wouldn’t have been due to a county policy.

In response to the Raymond lawsuit, defendants argued that qualified immunity applied, jail staff had no reason to believe Raymond was at risk of suicide, and no county policy led to a violation of his rights.

Quitman County settled both lawsuits for undisclosed sums. The sheriff and county officials other than Scipper did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Once people are booked into jail, there are nationally accepted guidelines on what staff should do to prevent people from killing themselves.

People who are seriously mentally ill are “naturally at higher risk for suicide,” said Dr. Brent Gibson, former chief health officer at the National Commission on Correctional Health Care and founder of the health care consulting company Avocet Enterprises. “All of these people should be directly observed in some kind of way.”

Staff should check on people at risk of suicide at irregular intervals of no more than 15 minutes, according to standards developed by the National Commission on Correctional Health Care. People who are trying to hurt themselves or say they plan to do so should be watched constantly. At-risk inmates should be housed in cells that are “suicide-resistant.” If necessary, their clothes and bedding should be replaced with smocks and blankets made of thick, sturdy material.

Before all nine suicides in Mississippi jails, those things didn’t happen — in part because at least two inmates were never screened in the first place — according to depositions, Mississippi Bureau of Investigation reports and jail records. Just one person was put on suicide watch and housed in a suicide-resistant cell. At least eight weren’t monitored as frequently as guidelines say. At least seven of the eight who hanged themselves weren’t provided with special clothing or blankets. At one jail, the policy was to put someone on suicide watch only if they had attempted suicide there.

Quitman County Sheriff Oliver Parker said in a deposition that his staff did not keep an especially close eye on Raymond because his commitment did not stem from a suicide attempt.

In 2019, 12 years after Raymond died, Brian Sneed was booked into the Quitman County jail without criminal charges as he awaited a drug rehab bed. When the 52-year-old welder was discovered dead from suicide, it had been more than an hour since jail staff had checked on him, according to a Mississippi Bureau of Investigation report.

“They may die out on the street — I can’t say they don’t. But in a jail cell is just not a good spot for them.”

Quitman County Chancery Clerk Butch Scipper

After Sneed’s death, Scipper concluded he couldn’t guarantee people waiting for treatment would be safe in jail. “I said right then, they may die out on the street — I can’t say they don’t,” he said in an interview. “But in a jail cell is just not a good spot for them.”

Now, he tells people to wait at home until a publicly funded treatment bed is available. Nothing in state law prohibits that, though the state Department of Mental Health says people who are well enough to wait at home may not actually need to be committed.

When The Doctor’s Waiting Room is a Jail Cell

The bare-bones medical care in many Mississippi jails can be dangerous for people who are mentally ill even if they aren’t suicidal.

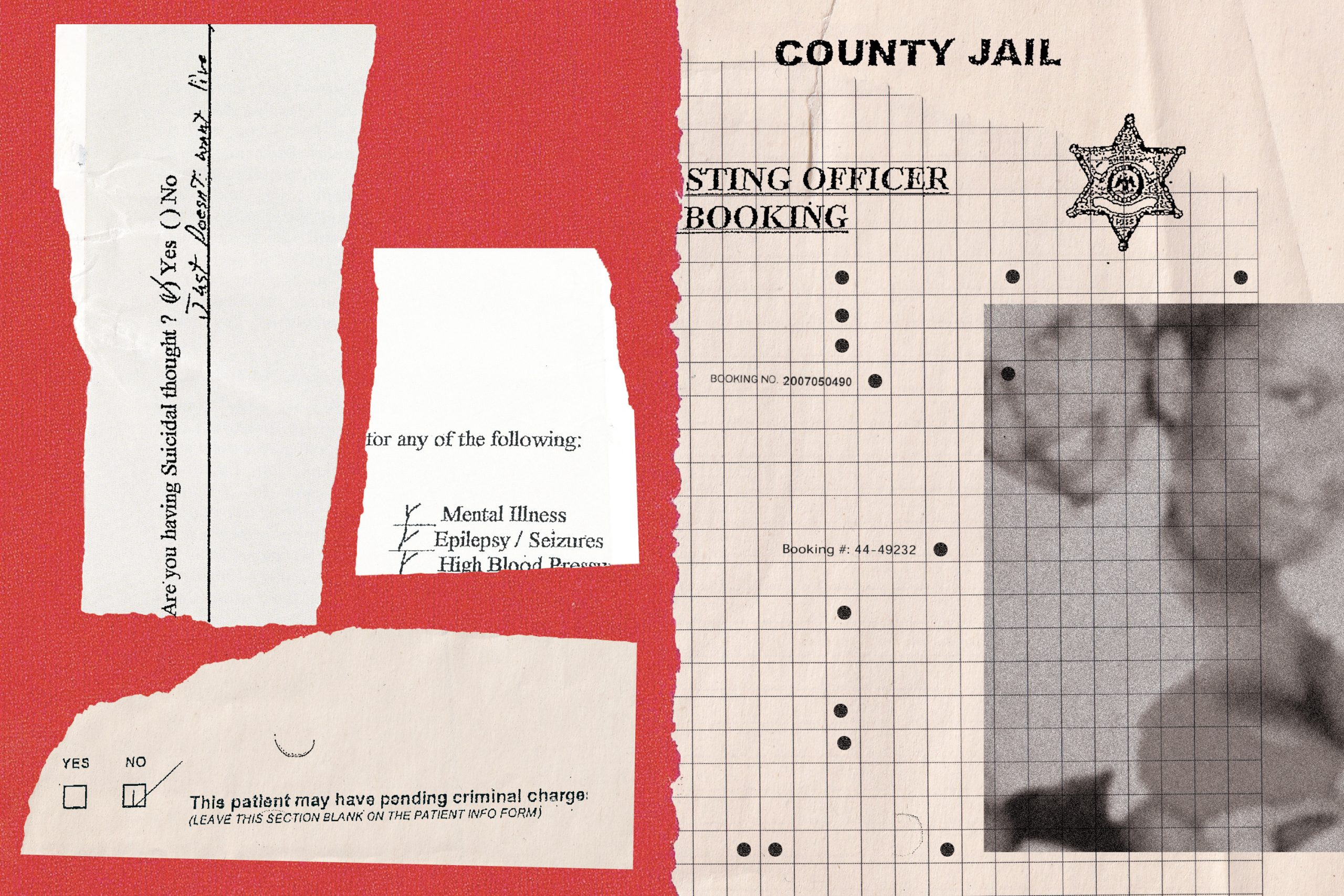

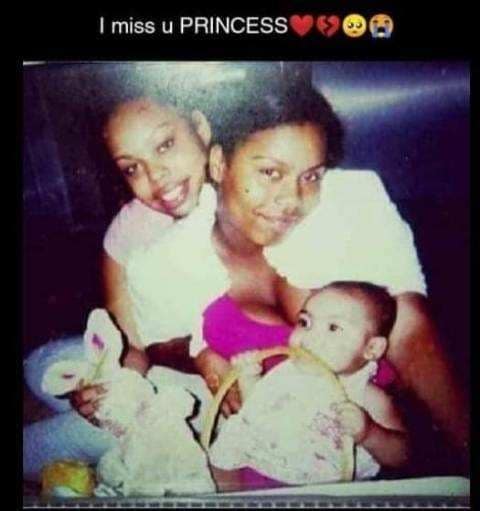

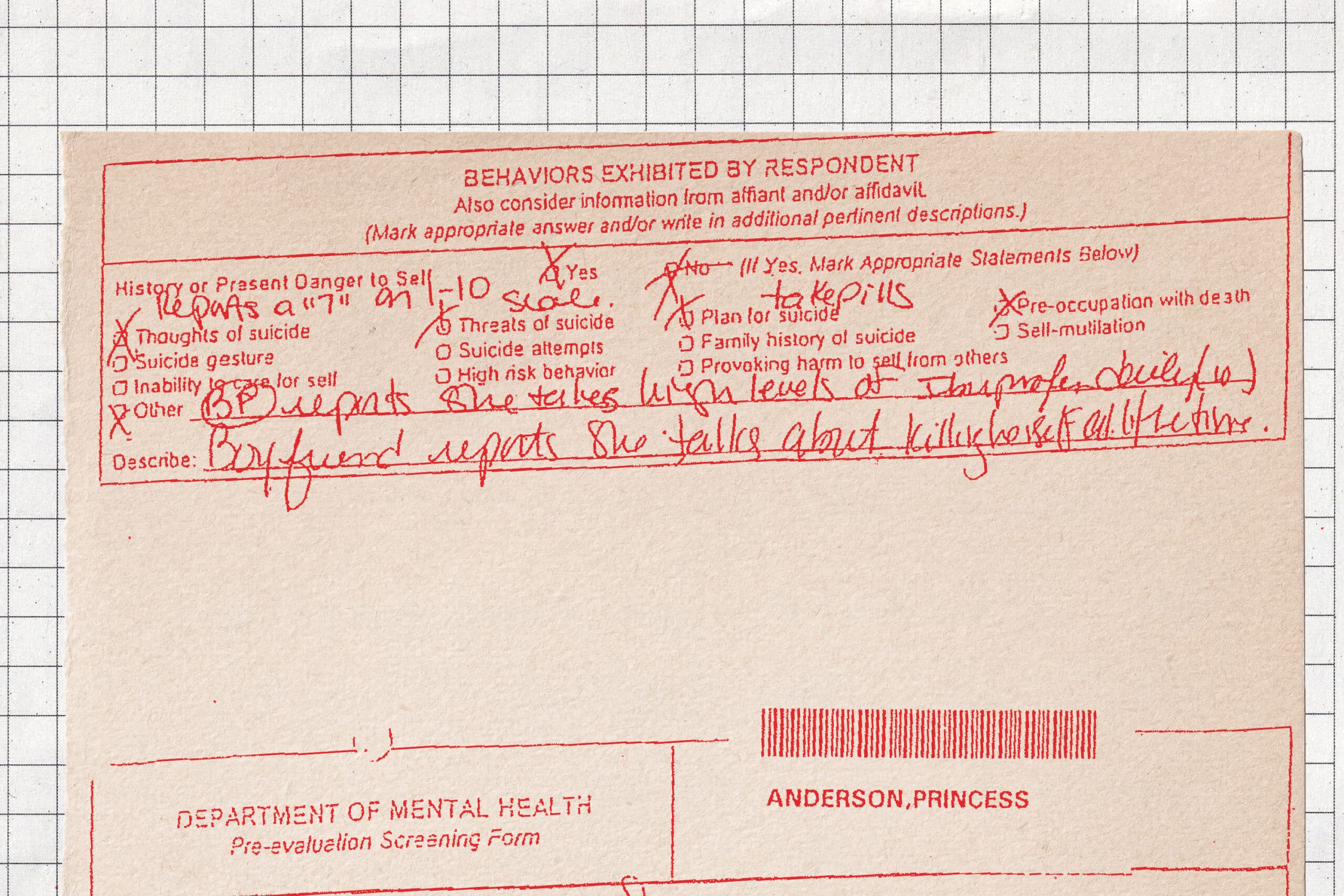

Over the three days that Princess Anderson was held in the Marshall County jail awaiting a commitment hearing in February 2011, her physical condition declined precipitously. Jail staff did little to inquire about her medical history, according to depositions in a lawsuit later filed over her death. And staff failed to call for help as she exhibited signs of medical distress.

“I would never ever thought in my life that anything like this would ever go on, you know, what happened to my child. … They’re supposed to be protecting you. They supposed to be caring for you.”

Angela Anderson, mother of Princess Anderson

By the time Anderson arrived at a hospital, “she may very well have been one of the sickest patients I’ve ever seen,” her attending physician in the intensive care unit testified in that lawsuit.

Anderson’s journey through the commitment process had started four days before, when she went to a hospital near Memphis and learned she might be suffering from an ectopic pregnancy, a painful and possibly fatal condition. She was released but later that day went to Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto, where she reported that she had ingested cough syrup and marijuana and complained of nausea and anxiety. After she shoved nurses and screamed that she was going to die, a mental health assessor working on behalf of the hospital filed paperwork to have her involuntarily committed.

Anderson was taken in shackles from the hospital to the jail in neighboring Marshall County, where she lived, to await a psychiatric evaluation. On one jail document, her “most serious charge” was recorded as “LUNACY.”

Booking officer Adella Anderson, who is not related to Princess Anderson, handled the medical screening. Princess Anderson didn’t respond to her questions, so the booking officer later testified that she filled out the screening form with the limited information in the commitment paperwork.

Experts said the booking officer should not have simply stopped her inquiries because Anderson didn’t respond; she should have asked a mental health professional to gather more information.

The booking officer testified that she knew Anderson had been brought from a hospital but didn’t find out why. She said she didn’t open an envelope containing Anderson’s medical records because she thought that was illegal. (The law allows correctional staff to review medical records if necessary, but experts said such staff should be trained in doing so, and she was not.) If she had opened the envelope, she might have seen hospital paperwork about the ectopic pregnancy.

Gibson said he has seen “numerous deaths” occur after a jail staffer gave up on a medical screening because an inmate didn’t provide information. “If someone is literally not responsive, they probably shouldn’t be in the jail at all — they should be in the hospital,” he said.

Efforts to reach Adella Anderson by email, phone and mail were unsuccessful.

The next day, an employee of Communicare, the local community mental health center, tried to evaluate Princess Anderson. Again, she was “unresponsive,” according to the form that therapist Debra Shelton filled out. Shelton used paperwork from the hospital to complete the form, concluding that Anderson had tried to harm herself after learning she was pregnant. “Recommend immediate transfer to hospital” for psychosis, Shelton wrote. (Efforts to reach her for this story were unsuccessful.)

Instead of being hospitalized, Anderson was left alone in her cell with inconsistent monitoring until she could be evaluated further as part of the commitment process.

If she had been in a state psychiatric hospital, medical professionals would have routinely checked her vital signs. That’s important because people with mental illness may not recognize signs of physical illness and ask for help, correctional health care experts said. In jail, however, none of the staff were required to have any medical training aside from CPR.

Over the next two days, Anderson’s condition became increasingly concerning to those around her — but not to jail staff, according to depositions.

She removed her clothes and, according to an inmate’s testimony, lay on the floor in a pool of water for hours at a time. “There wasn’t nothing abnormal for her to get on the floor,” the booking officer later testified. “Most lunacies do that.”

Anderson got sicker. She barely spoke. Her fingers bled from scratching the walls. When she foamed at the mouth, inmates beat on a cell block door for help and told jailers they thought she was having a seizure. Two inmates called 911. Even “the church people” who regularly came to the jail tried to get staff to call an ambulance, one inmate testified.

The booking officer later testified that she didn’t take those calls for help seriously. Inmates “do that with everybody,” she said.

Greifinger, the former chief medical officer for the New York state prison system, said that kind of thinking is common among correctional staff around the country. Even when they see an inmate vomiting or know someone hasn’t eaten for days, he said, “there’s a tremendous culture of disbelief that’s rampant.”

Meanwhile, Anderson’s mother, Angela Anderson, found hospital paperwork saying her daughter might have an ectopic pregnancy. Angela Anderson went to the courthouse to ask if she could take her daughter to a hospital for an ultrasound.

Sarah Liddy, the special master presiding over Princess Anderson’s commitment proceedings, allowed the young woman to leave the jail only after her mother signed a document promising to pay for her medical care. Liddy didn’t respond to a request for comment for this article.

When Angela Anderson arrived at the jail, she found a horrifying scene, according to her testimony. Her daughter was lying on the floor, in two inches of water, feces and vomit. Her fingernails were broken off and there was blood on the walls. Princess was unconscious, only able to groan. Angela begged jail staff to call 911, testifying later that she felt “like a fool” for calling for help from inside a jail.

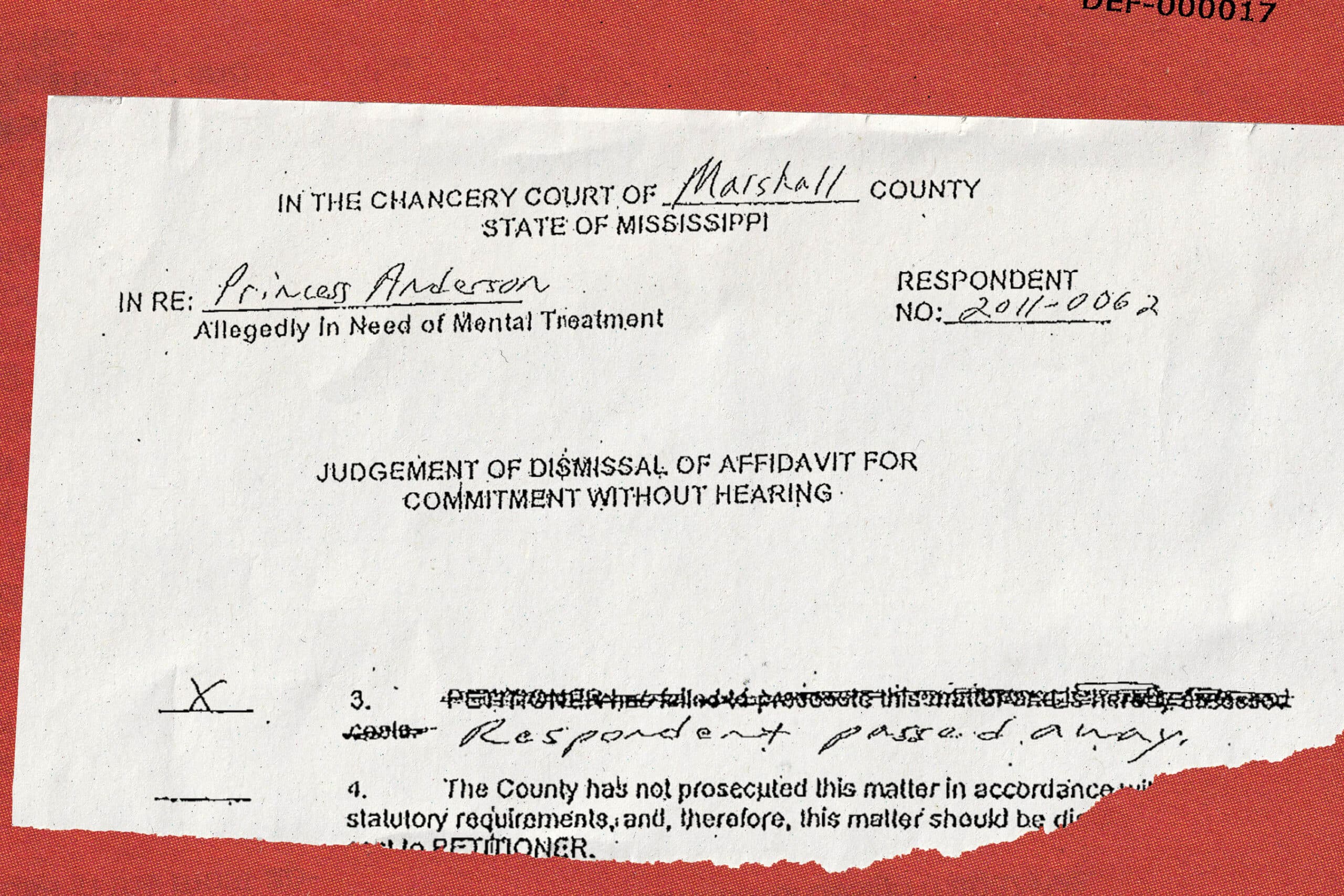

Princess Anderson was admitted to an ICU with a diagnosis of psychosis, acute renal failure, a metabolic disorder and sepsis. She died a month later at the same hospital where staff had started the legal process that landed her in jail.

According to her autopsy report, Anderson may have experienced a miscarriage in jail. Based on the autopsy and the available information, a medical examiner concluded that she died from multisystem organ failure of an unknown cause.

Dr. Marc F. Stern, a professor at the University of Washington and former medical director for the Washington State Department of Corrections, reviewed key facts of Anderson’s case. He said the behavior that caused hospital staff to initiate commitment proceedings may have been caused by an underlying medical issue.

What happened to Anderson, he said, shows that Mississippi’s practice of jailing people who need medical care is “dangerous, unconscionable, and inhumane.”

‘Ignoble, Sordid, Upsetting, and Tragic.’ But Not Unconstitutional.

When Anderson died, her mother sued Marshall County and Sheriff Kenny Dickerson, as well as Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto. Hers was one of at least nine lawsuits filed by families seeking to hold accountable the people who had detained their loved ones.

Outside of criminal charges, such lawsuits are typically the only option relatives have. Eight of those suits have run their course; none have resulted in court rulings holding anyone liable.

Unlike the vast majority of Americans, incarcerated people have a constitutional right to health care, thanks to a 1976 Supreme Court decision. But in order to prove that insufficient medical care violated an inmate’s constitutional rights, a plaintiff must demonstrate “deliberate indifference” — that staff knew an inmate needed medical attention or was at risk of suicide, but did little or nothing in response.

“That’s a super hard standard to meet,” said Michele Deitch, an expert on jail oversight and director of the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin. “You have to get into the head of the person who caused harm,” she said. “They had to know there was a risk of serious harm, and then they did this thing anyway, not caring.”

Princess Anderson’s mother couldn’t meet that standard.

Her suit alleged the sheriff’s office was deliberately indifferent to Princess Anderson’s medical needs. Attorneys representing the sheriff and the county argued the sheriff was entitled to qualified immunity and that jail staff had taken measures to care for Anderson, pointing out that hospital staff had medically cleared her to be taken to jail. The sheriff and other county officials didn’t respond to inquiries for this article.

The suit also alleged that the hospital failed to diagnose the cause of Princess Anderson’s altered mental state and stabilize her and that it handed her over to deputies without proper instructions. In response, the hospital argued that it was protected by a provision of Mississippi law that says anyone “acting in good faith” during the civil commitment process can’t be held liable.

A federal judge dismissed the case against the sheriff based on qualified immunity. The county was later dismissed as a defendant because jail policies were not the “moving force” behind Anderson’s death and jail staff had “periodically” monitored her.

“Officers observed Anderson’s pattern of taking off her clothes and lying on the floor, but they found this conduct to be consistent with other mentally ill inmates at the jail,” U.S. District Judge Debra M. Brown wrote in her December 2014 opinion.

Angela Anderson appealed that decision to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. In their ruling, circuit judges called Princess Anderson’s death “ignoble, sordid, upsetting, and tragic.” But they agreed that Anderson’s mother had not proven that officials had acted with deliberate indifference.

All of the lawsuits filed over these deaths alleged the care provided in jail demonstrated deliberate indifference. In the three cases in which judges issued rulings, none found those arguments persuasive.

Anderson’s suit against the hospital eventually went to trial in state court. A jury sided with the hospital.

In an email, Baptist Memorial Health Care’s director of public relations, Kim Alexander, wrote of Princess Anderson, “I am confident our medical team did everything they could to help her and provide compassionate treatment while she was in our care.”

“We are saddened by outcomes like Ms. Anderson’s,” Alexander wrote, “and fully support efforts by our state and mental health professionals to refine our mental health system.”

Eight of the nine counties where people died as they went through the commitment process, including Marshall County, still jail those people. Quitman, where Scipper works, no longer does.

Do you have a story to share about someone who went through the civil commitment process in Mississippi? Contact Isabelle Taft at itaft@mississippitoday.org or call her at (601) 691-4756.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Mississippi River flooding Vicksburg, expected to crest on Monday

Warren County Emergency Management Director John Elfer said Friday floodwaters from the Mississippi River, which have reached homes in and around Vicksburg, will likely persist until early May. Elfer estimated there areabout 15 to 20 roads underwater in the area.

“We’re about half a foot (on the river gauge) from a major flood,” he said. “But we don’t think it’s going to be like in 2011, so we can kind of manage this.”

The National Weather projects the river to crest at 49.5 feet on Monday, making it the highest peak at the Vicksburg gauge since 2020. Elfer said some residents in north Vicksburg — including at the Ford Subdivision as well as near Chickasaw Road and Hutson Street — are having to take boats to get home, adding that those who live on the unprotected side of the levee are generally prepared for flooding.

“There are a few (inundated homes), but we’ve mitigated a lot of them,” he said. “Some of the structures have been torn down or raised. There are a few people that still live on the wet side of the levee, but they kind of know what to expect. So we’re not too concerned with that.”

The river first reached flood stage in the city — 43 feet — on April 14. State officials closed Highway 465, which connects the Eagle Lake community just north of Vicksburg to Highway 61, last Friday.

Elfer said the areas impacted are mostly residential and he didn’t believe any businesses have been affected, emphasizing that downtown Vicksburg is still safe for visitors. He said Warren County has worked with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency to secure pumps and barriers.

“Everybody thus far has been very cooperative,” he said. “We continue to tell people stay out of the flood areas, don’t drive around barricades and don’t drive around road close signs. Not only is it illegal, it’s dangerous.”

NWS projects the river to stay at flood stage in Vicksburg until May 6. The river reached its record crest of 57.1 feet in 2011.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

With domestic violence law, victims ‘will be a number with a purpose,’ mother says

Joslin Napier. Carlos Collins. Bailey Mae Reed.

They are among Mississippi domestic violence homicide victims whose family members carried their photos as the governor signed a bill that will establish a board to study such deaths and how to prevent them.

Tara Gandy, who lost her daughter Napier in Waynesboro in 2022, said it’s a moment she plans to tell her 5-year-old grandson about when he is old enough. Napier’s presence, in spirit, at the bill signing can be another way for her grandson to feel proud of his mother.

“(The board) will allow for my daughter and those who have already lost their lives to domestic violence … to no longer be just a number,” Gandy said. “They will be a number with a purpose.”

Family members at the April 15 private bill signing included Ashla Hudson, whose son Collins, died last year in Jackson. Grandparents Mary and Charles Reed and brother Colby Kernell attended the event in honor of Bailey Mae Reed, who died in Oxford in 2023.

Joining them were staff and board members from the Mississippi Coalition Against Domestic Violence, the statewide group that supports shelters and advocated for the passage of Senate Bill 2886 to form a Domestic Violence Facility Review Board.

The law will go into effect July 1, and the coalition hopes to partner with elected officials who will make recommendations for members to serve on the board. The coalition wants to see appointees who have frontline experience with domestic violence survivors, said Luis Montgomery, public policy specialist for the coalition.

A spokesperson from Gov. Tate Reeves’ office did not respond to a request for comment Friday.

Establishment of the board would make Mississippi the 45th state to review domestic violence fatalities.

Montgomery has worked on passing a review board bill since December 2023. After an unsuccessful effort in 2024, the coalition worked to build support and educate people about the need for such a board.

In the recent legislative session, there were House and Senate versions of the bill that unanimously passed their respective chambers. Authors of the bills are from both political parties.

The review board is tasked with reviewing a variety of documents to learn about the lead up and circumstances in which people died in domestic violence-related fatalities, near fatalities and suicides – records that can include police records, court documents, medical records and more.

From each review, trends will emerge and that information can be used for the board to make recommendations to lawmakers about how to prevent domestic violence deaths.

“This is coming at a really great time because we can really get proactive,” Montgomery said.

Without a board and data collection, advocates say it is difficult to know how many people have died or been injured in domestic-violence related incidents.

A Mississippi Today analysis found at least 300 people, including victims, abusers and collateral victims, died from domestic violence between 2020 and 2024. That analysis came from reviewing local news stories, the Gun Violence Archive, the National Gun Violence Memorial, law enforcement reports and court documents.

Some recent cases the board could review are the deaths of Collins, Napier and Reed.

In court records, prosecutors wrote that Napier, 24, faced increased violence after ending a relationship with Chance Fabian Jones. She took action, including purchasing a firearm and filing for a protective order against Jones.

Jones’s trial is set for May 12 in Wayne County. His indictment for capital murder came on the first anniversary of her death, according to court records.

Collins, 25, worked as a nurse and was from Yazoo City. His ex-boyfriend Marcus Johnson has been indicted for capital murder and shooting into Collins’ apartment. Family members say Collins had filed several restraining orders against Johnson.

Johnson was denied bond and remains in jail. His trial is scheduled for July 28 in Hinds County.

He was a Jackson police officer for eight months in 2013. Johnson was separated from the department pending disciplinary action leading up to immediate termination, but he resigned before he was fired, Jackson police confirmed to local media.

Reed, 21, was born and raised in Michigan and moved to Water Valley to live with her grandparents and help care for her cousin, according to her obituary.

Kylan Jacques Phillips was charged with first degree murder for beating Reed, according to court records. In February, the court ordered him to undergo a mental evaluation to determine if he is competent to stand trial, according to court documents.

At the bill signing, Gandy said it was bittersweet and an honor to meet the families of other domestic violence homicide victims.

“We were there knowing we are not alone, we can travel this road together and hopefully find ways to prevent and bring more awareness about domestic violence,” she said.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mississippi Today

Court to rule on DeSoto County Senate districts with special elections looming

A federal three-judge panel will rule in coming days on how political power in northwest Mississippi will be allocated in the state Senate and whether any incumbents in the DeSoto County area might have to campaign against each other in November special elections.

The panel, comprised of all George W. Bush-appointed judges, ordered state officials last week to, again, craft a new Senate map for the area in the suburbs of Memphis. The panel has held that none of the state’s prior maps gave Black voters a realistic chance to elect candidates of their choice.

The latest map proposed by the all-Republican State Board of Election Commissioners tweaked only four Senate districts in northwest Mississippi and does not pit any incumbent senators against each other.

The state’s proposal would keep the Senate districts currently held by Sen. Michael McLendon, a Republican from Hernando and Sen. Kevin Blackwell, a Republican from Southaven, in majority-white districts.

But it makes Sen. David Parker’s district a slightly majority-Black district. Parker, a white Republican from Olive Branch, would run in a district with a 50.1% black voting-age population, according to court documents.

The proposal also maintains the district held by Sen. Reginald Jackson, a Democrat from Marks, as a majority-Black district, although it reduces the Black voting age population from 61% to 53%.

Gov. Tate Reeves, Secretary of State Michael Watson, and Attorney General Lynn Fitch comprise the State Board of Election Commissioners. Reeves and Watson voted to approve the plan. But Watson, according to meeting documents, expressed a wish that the state had more time to consider different proposals.

Fitch did not attend the meeting, but Deputy Attorney General Whitney Lipscomb attended in her place. Lipscomb voted against the map, although it is unclear why. Fitch’s office declined to comment on why she voted against the map because it involves pending litigation.

The reason for redrawing the districts is that the state chapter of the NAACP and Black voters in the state sued Mississippi officials for drawing legislative districts in a way that dilutes Black voting power.

The plaintiffs, represented by the ACLU, are likely to object to the state’s newest proposal, and they have until April 29 to file an objection with the court

The plaintiffs have put forward two alternative proposals for the area in the event the judges rule against the state’s plans.

The first option would place McLendon and Blackwell in the same district, and the other would place McLendon and Jackson in the same district.

It is unclear when the panel of judges will issue a ruling on the state’s plan, but they will not issue a ruling until the plaintiffs file their remaining court documents next week.

While the November election is roughly six months away, changing legislative districts across counties and precincts is technical work, and local election officials need time to prepare for the races.

The judges have not yet ruled on the full elections calendar, but U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Leslie Southwick said at a hearing earlier this month that the panel was committed have the elections in November.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days agoJim talks with Rep. Robert Andrade about his investigation into the Hope Florida Foundation

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days agoHighs in the upper 80s Saturday, backdoor cold front will cool us down a bit on Easter Sunday

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days agoValerie Storm Tracker

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days agoU.S. Supreme Court pauses deportations under wartime law

-

Mississippi Today5 days ago

Mississippi Today5 days ago‘Trainwreck on the horizon’: The costly pains of Mississippi’s small water and sewer systems

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days agoPrayer Vigil Held for Ronald Dumas Jr., Family Continues to Pray for His Return | April 21, 2025 | N

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days agoMeteorologist Chita Craft is tracking a Severe Thunderstorm Warning that's in effect now

-

Mississippi Today7 days ago

Mississippi Today7 days agoOn this day in 1977, Alex Haley awarded Pulitzer for ‘Roots’