Jay Feinman, Rutgers University

The wildfires that have devastated large parts of Los Angeles County have drawn fresh attention to the struggles many Americans face insuring their homes.

Since 2022, seven of the 12 largest insurance companies have stopped issuing new policies to homeowners in California, citing increased risks due to climate change. California isn’t alone: The same thing has happened in other vulnerable states, including Louisiana and Florida. The proportion of Americans without home insurance has risen from 5% to 12% since 2019. Meanwhile, those fortunate enough to have insurance are paying more than ever: Premiums in California, like elsewhere, have increased dramatically over the past five years.

When the private insurance market fails to provide coverage, the government often comes in to fill the gap. For example, the National Flood Insurance Program was established back in the 1960s because almost all private insurers excluded flood coverage. Meanwhile, the California FAIR Plan, which serves more than 450,000 Californians, is a typical state-created insurer of last resort. Such programs, which are available in many states, offer limited coverage to people who can’t get private insurance.

But the sheer scale of need means it’s hard for public programs to stay afloat. It’s not inconceivable that the recent wildfires could exceed the reserves and reinsurance available to the California FAIR plan. Because of the way the plan is set up, that would force other insurers – and ultimately homeowners – to make up the difference.

These are tricky problems, and – speaking as an expert in insurance – I can’t say I have answers. But I do know the right questions to ask. And that’s a crucial first step if you want to find solutions.

What is insurance for, anyway?

One of the most important questions is also the most basic: What are the goals of insurance?

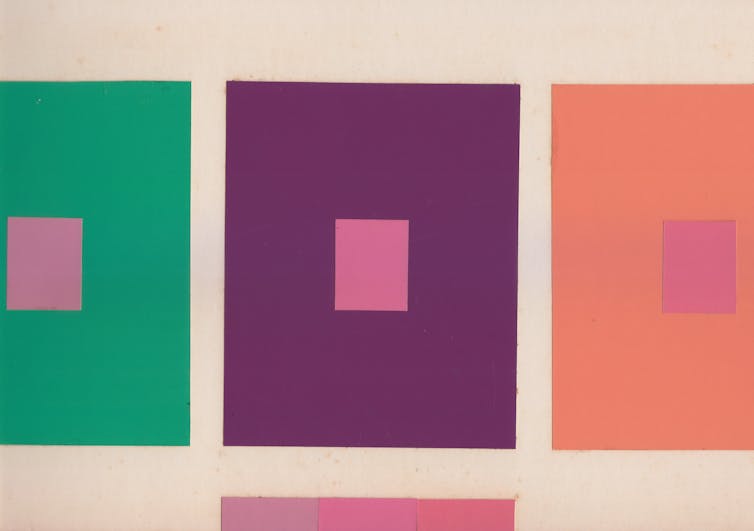

Insurance is a financial product that allows people to share risk – meaning that if a catastrophe strikes any one person, they won’t have to bear the costs alone. But it’s not just about money. Even if most people don’t realize it, every form of insurance embodies values and serves public policy goals. This often requires making social, political and even moral trade-offs.

What is the problem we’re trying to solve?

The first step in solving a problem is to identify it. When it comes to insurance, this isn’t always easy. For example, “Homeowners need insurance coverage that they can’t afford in the private market” might seem like a good description of the problem. But it’s not. This is because some homes in disaster-prone areas are simply too risky to insure.

Imagine a home in a coastal area that floods over and over, for example. If you were an insurer, how much would you charge for that policy? When a house is subject to repeated losses, it makes more economic sense to buy and demolish it instead.

Defining the problem carefully also helps to clarify the values at stake. For example, one value is protecting the investments of current homeowners – particularly, say, long-time, elderly residents. But another value is pricing risk correctly, so people don’t move into dangerous developments.

Put more broadly, one value is recognizing society’s collective responsibility toward people who suffer financial distress, and another is promoting fair and efficient use of social resources. These values can be in conflict.

What does the government have to do with insurance?

Back in 1881, in his classic lectures on The Common Law, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. said:

The state might conceivably make itself a mutual insurance company against accidents and distribute the burden of its citizens’ mishaps among all its members. There might be a pension for paralytics, and state aid for those who suffered in person or estate from tempest or wild beasts.

Holmes’ own position was clear: “The state does none of these things,” he wrote – and it should not. This strain of individualism has remained strong in U.S. politics: Individual liberty, personal responsibility and economic opportunity are the foundations of American life, individualists say, so each person should win or lose on their own.

Under this approach, the private insurance market bases its pooling, risk classification and pricing mostly on how much risk each policyholder presents, so that homes in wildfire-prone areas are charged higher premiums. In theory, this is both morally sound and economically efficient, since each policyholder bears the cost of their own risks. But when the private market fails – as happened with flood insurance – the government has a strong incentive to step in.

Today, as an empirical matter, Holmes’ statement couldn’t be more wrong. The state does, in fact, make itself “a mutual insurance company against accidents” and provides a “pension for paralytics,” through Medicaid, Social Security Disability Insurance and other programs. And in California, as elsewhere, the government does provide aid for those who “suffered in estate … from tempest,” through the Federal Emergency Management Agency and other entities.

Since at least the New Deal, there has been broad recognition that some level of collective responsibility is essential; the only questions are where and how much. In the health insurance realm, for example, the Affordable Care Act provides subsidized health insurance for many Americans, and changing Medicare is a political third rail.

Public policy on disaster losses is situated between the two extremes of letting losses lie and having the state assume all of the burdens of those losses. Often policymakers and researchers see insurance or insurance-like plans as solutions – whether provided by a public entity or involving a mixed public-private program. FEMA, for example, operates the National Flood Insurance Program in cooperation with private insurers and also gives direct grants for mitigation of flood damage.

What should a public insurance solution look like?

Sometimes one question leads to another, and that’s the case here. In my research, I’ve identified more than a dozen questions that policymakers must answer in order to design an effective public solution to disaster insurance. Three questions are most important:

• What are the goals of the insurance?

• Who is being insured?

• How are policyholders and their risks classified?

Let’s start with the first question: What are the goals of the insurance? As I mentioned earlier, any form of insurance faces trade-offs and limits.

When an insurance solution has been adopted rather than some other form of intervention, a primary goal is to compensate the policyholder for a loss. But that’s not the only goal. For example, insurance often aims to reduce losses in addition to paying if they occur. Insurers have many ways to shape behavior, such as charging lower premiums for homeowners who keep their property free of flammable brush. Because many of these behaviors affect other people as well, they generate a social benefit. And since insurance has social benefits, how those benefits are distributed – along race, gender, class and other lines – is also important.

A home in Altadena, Calif., is consumed by flames due to the Eaton Fire on Jan. 8, 2025.

That leads to the second key question: Who is being insured?

Insurance involves transferring risk from an individual to a larger group of people who can share the risk. Insurance experts call this “risk pooling.” Pools that are too small will struggle because there aren’t enough people to share the burden.

In public solutions to catastrophe problems, getting more people in the pool could be especially useful in expanding coverage. For example, the National Flood Insurance Program brings many homeowners across the country into a pool, but it also excludes some, such as those who suffer damage from wind during a hurricane. In contrast, the proposed INSURE Act, introduced in the last Congress, would effectively put the entire nation in a pool to cover a variety of catastrophic risks, including flood, wildfire, earthquake and others.

Still, just because you’re in the same pool as someone else doesn’t mean you’ll be treated the same – people with the same insurance can be charged different premiums and receive different amounts of coverage.

That leads to the third question: How are policyholders and their risks classified?

If insurers treated everybody exactly the same, they would quickly go out of business. That’s why they analyze huge amounts of information about past losses, current conditions and future predictions, trying to determine the risks posed by each member. This work is done by actuaries and underwriters, but it’s not just a matter of math: Insurers classify policyholders in ways that reflect the goals and values of the insurance, which typically include balancing widespread availability, broad coverage and affordable pricing, and the social benefits the insurance generates.

One view of this process is that more precise risk classification and pricing are good. Because insurance involves risk transfer, the more accurately risks can be calculated and priced, the better the process works.

But there’s a deeper problem, which has to do with values. Sometimes accuracy in underwriting can conflict with larger social goals. With catastrophes in particular, broad coverage may be a top priority, since many people believe the state has a responsibility to protect its people. Moreover, protecting people’s investments in their homes is important, and suddenly raising the premiums of homeowners at high risk would threaten their investments. Disasters also cause communal responses – many unaffected Americans donate to the Red Cross and other nonprofits to support victims – and a strict focus on accuracy in underwriting could undermine that sense of community.

As floods, storms, wildfires and other catastrophes become increasingly common, the availability and affordability of property insurance has become a high-profile political issue. Politics involve choices. Asking better questions will help politicians – and the rest of us – make better choices.![]()

Jay Feinman, Distinguished Professor of Law Emeritus, Rutgers University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.