Mississippi Today

In this shrinking Mississippi Delta county, getting a college degree means leaving home behind

ISSAQUENA COUNTY — The kings and queens of the South Delta School District tossed candy and waved at their families as the mid-October parade wound through a small town several miles north of this rural county.

“There’s no place like homecoming,” read a sign on a colorful “Wizard of Oz” themed float with a picture of Emerald City on the back.

Homecoming in Issaquena County, the least populated county in Mississippi — and one of the smallest in the country — is so popular that locals call it “South Delta University.”

But there is no college here, not for miles and miles; in fact, there is no public school of any kind. Students from Issaquena County attend school in neighboring counties — and it’s a big reason why many of these kids will have no choice when they grow up but to move away.

There are virtually no jobs for college graduates in this rural county blanketed in farm fields of soybeans, cotton and corn. There are no factories and no hospitals in Issaquena County. There are no public schools – haven’t been for decades. The median household income is roughly $24,000, a little more than half of the statewide average.

A single statistic underscores all these factors. Here, out of the county’s 1,111 residents, just an estimated 42 people aged 25 and older have a bachelor’s degree — meaning Issaquena County’s population has one of the lowest rates of educational attainment in America.

That’s not because people from this county aren’t going to college. Many of their families want them to get a degree — and then leave.

There’s little appetite or means in Issaquena to change this reality, a product of generations of decisions that favored powerful, largely white land interests over education and jobs.

“All my grandkids, they’re going to college,” said Norah Fuller, a Black farm manager, as he watched the football game that Friday night. “I’m going to make sure they’re going to college. Do we want the kids to stay? No. What they gonna stay here for?”

Unless his grandchildren want to work on a farm, it’s hard to say. Outside of local government and a prison, the primary source of jobs are the farms that have existed since before the Civil War. But these days, the white families who own much of the land in a county that’s 63% Black are hiring less, and they have little incentive to make room for industries or jobs that could bring college-educated people back.

Fuller himself left the area, dropping out of school in the early 1960s. He didn’t come back until he felt mentally ready to do the same kind of labor enslaved people in this area did.

“I had to get away,” he said. “I stayed away until I could handle it.”

So the cycle continues in Issaquena: Year after year, more and more people move away, leaving behind fewer reasons for anyone else to stay, for any change to happen, and more reasons for young, educated people to go.

“Around here, that’s really the only way you’re gonna make money,” said Amber Warren, a 29-year-old mom who has an associate’s degree and has tried to get a job in Issaquena that will support her three kids. After years of applying, she finally landed one as a caseworker aid last year making $11-an-hour.

Now she’s searching for a better-paying job, up the hills and out of the Delta, away from all her family.

Issaquena County is flat, desolate and strikingly more rural than anywhere else in Mississippi. The famous “blues highway” largely skirts this southwestern corner of the Delta, where much of the traffic consists of pickups, tractors and trailers. Along the river looms a grassy levee that’s rivaled in height only by large silver grain bins and silos.

The county has been in a state of economic depression for decades. But that didn’t happen overnight.

The story of this fertile land starts in 1820, when it was ceded by the Choctaw, whose words for “deer river” form “Issaquena.” Wealthy settlers — cotton farmers from the east — swooped in and set up plantations. By the eve of the Civil War, a vast majority of the nearly 100 farm operators in Issaquena owned enslaved people, who made up 93% of the county’s population, the highest percentage in Mississippi.

Reconstruction did little to change this imbalance of power. Agriculture continued to dominate the local economy. The “wild lands” were cheap, and Mayersville, the county seat, became something of a boom town, replete with hotels and saloons as the area grew to more than 10,000 people.

Soon politicians, businessmen and planters all over the Delta were vying for a railroad to come through their town, eager for alternatives to the crumbling, unpaved roads.

Issaquena’s landowners resisted, believing their land could get a higher price from the railroad companies. That wasn’t the case. The county was circumvented, and Issaquena, as one newspaper in 1902 put it, had “repented” ever since. A few logging rails run through the county today.

Thus began Issaquena’s first major population decline. Mayersville was soon considered the last undeveloped place in the Delta. By the 1930s, the county’s population had shrunk to less than 6,000. Nearly all of the farms were operated by sharecroppers.

Around this time, Stan Delaney’s grandfather crossed the river from Arkansas to Mayersville and, with money he’d saved from managing a farm, bought land. Delaney grew up on it. He learned to drive a tractor when he was 7, and he dropped out of the newly formed, private Sharkey-Issaquena Academy in his senior year to farm, working alongside a Black family, the Wallaces, that his dad employed.

The Wallaces have since moved away, Delaney said. Today, Delaney’s wife and son help him work the family’s roughly 1,150 acres, which are worth about $1 million. One of the county’s 189 farm producers who are white, Delaney rents the land from his mother.

His daughter, Whitney Delaney, went to college because she didn’t now want to farm. Now she figures she makes less working in a local community college’s student services than her brother does in farming.

Delaney wants to see more young people in Issaquena — especially so his 28-year-old son can meet someone. He knows industry could bring that. But he’d never dream of selling the land to make way for something different. If his kids didn’t feel the same, he’d set up a trust so it could never be sold.

“My dad worked so hard, and my grandfather worked so hard and sacrificed,” he said. “That’s your tradition, that’s just your Southern tradition.”

Like everything else here, the brick building four minutes from Mayersville on Highway 1 is surrounded by fields. Bales of cotton bound in bright yellow plastic greet visitors driving down the gravel road to the Head Start. The school, which opened in 1964, is Issaquena’s sole educational institution.

LaSonya Coleman logs attendance on her sherbert-green office’s desktop computer around 10 a.m. As the center manager, she oversees the development of 41 students. Just seven, she said, are from Issaquena.

Today, many residents, Black and white, aren’t troubled by Issaquena’s lack of public schools because the population is so small. In rural school districts across the country, consolidation is a common cost-saving measure.

But the reason why there are no public schools in Issaquena has nothing to do with population.

In 1952, the U.S. Supreme Court took up five cases that signaled it was going to rule on school segregation. Fearing the end of separate-but-equal, white lawmakers in Mississippi scrambled. In a special session, they passed a plan to finally “equalize” the white and Black schools, believing the ruling could be stopped if the state proved it actually funded separate-but-equal facilities equally.

It was a futile attempt. Instead, the plan threw into relief how unequal school funding really was: Black students received just 13% of education funding around that time, despite making up 57% of the school-age population.

In Issaquena, which had no white schools, the plan resulted in the shuttering of the school district, making it the first county in the state to not have one of its own. There was little reporting on the local fallout, but according to a 1988 article, Isssaquena’s 13 public schools closed too.

Yet Issaquena County has continued to pay taxes to support public schools that, aside from educating its residents, provide scant economic benefit to the county itself. South Delta is based in Sharkey County; the Western Line School District is in Washington County. Mississippi Delta Community College is 60 miles away in Moorhead.

Last year, Issaquena paid more than $937,000 in taxes to support all three institutions, the bulk going to South Delta, according to the county auditor.

“Having a school district does require college-educated people earning not great salaries, but still college-educated salaries, which helps in terms of property taxes, income taxes, all of the above,” said Toren Ballard, an analyst at Mississippi First, an education policy nonprofit.

Coleman, the Head Start director, had grown up just south of Issaquena in a tenant house her father designed and built on a plantation farm. A “country kid,” Coleman and her 14 siblings would play in a nearby creek while her dad worked the land and her mom, a housekeeper, cared for the farm owners’ kids.

In 1991, Coleman, wanting to explore after she got her associate’s degree at Hinds Community College, moved to Chicago. She worked at her sister’s daycare center. Four years later, she came back to the area after her dad was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He could no longer work on the farm, so he had to move out of the house.

By 2016, Coleman returned for good to find the area’s population even smaller than when she’d left. She said she would always tell her sister that local politicians should be working to bring more to the county, like a museum, something that isn’t seasonal like farming or school.

“I mostly stay to myself, but I do a lot of observing of what goes on in the community,” she said. “And I feel that they should bring the jobs in.”

If anyone wanted to bring more jobs to Issaquena County, it’d be tough to do it without talking to George Mahalitc first.

With more than 9,200 acres, Mahalitc is one of the largest private landowners in the county. His properties flank Mayersville to the north and south. In a classic tale of American success, his family moved to the area from Texas in 1961. Now, he may be the only farmer in Issaquena rich enough to grow cotton, an expensive crop. If a field is marked by bales of cotton wrapped in yellow, some locals say that probably means it’s Mahalitc’s land.

Mahalitc is also one of the county’s major employers. He hires tractor drivers and mechanics and workers for the cotton gin he owns with his brothers just over the county line in Washington County.

All told, Mahalitc employs about 30 people — something, he said, that’s getting harder to do.

He believes that Issaquena has no jobs for college graduates, and few jobs for anyone else, because its people don’t want to work. His point of view is not uncommon among farmers and landowners.

“What needs to happen is people need to get off their lazy tails and wanna go to work,” Mahalitc said. “Our government is subsidizing paying these people to sit at home. That’s the problem.”

But it doesn’t take long for Mahalitc to admit that farmers, by and large, want Issaquena to stay this way.

“Us farmers, we like it like that,” he said. “We don’t want the big population.”

As farmers have historically provided most of the jobs in Issaquena, they’ve also resisted efforts to develop the land that could bring other industries to the county, even as mechanization means they’re hiring less. And because just 26 farm producers in Issaquena are Black, most of the people protesting development in Issaquena are white.

Some farmers want more development. For Mahalitc, it depends on the project; he was interested in selling his land to a solar panel company that recently approached him but, he said, the company backed out.

Waye Windham, another white farmer and the county’s sheriff, said a decade ago, he would hire seven to eight workers for his farm of soybeans and corn. Now he hires two.

“We can’t stop looking for industry to come here,” he said. “If we do, we won’t ever find anybody.”

Yet in 1990, farmers across the tri-county area foiled the county board of supervisors’ efforts to get a $75 million hazardous waste incinerator. It would have created 79 permanent jobs and increased local tax revenues by an estimated $2.5 million at a time when cities and towns across the southern United States were competing to process each other’s trash.

And it was a rare opportunity: Issaquena is prone to backwater flooding that can destroy roads, homes and farmland, another factor that has limited the county’s economic opportunities.

Fearing the damage the waste could cause to local crops, a pair of farmers fiercely opposed it, writing op-eds and sending mailers to every registered voter in the county, which ultimately voted 413-315 against the plant.

Mahalitc was one of the 413. The plant would have been across his property line, and he was worried about his crops. Plus, he didn’t think anyone in Issaquena would be qualified to work at the plant.

“Where would they have qualified people to help run something like that?” Mahalitc said. “They’re not here.”

When the 376-bed Issaquena County Correctional Facility opened in 1997, it brought $1 million to the county tax rolls. Today it is the largest employer in the county — more than 50 people work there, but many are not from Issaquena — and it sits across Highway 1 from Mayersville. It, too, borders Mahalitc’s land.

Stallard Williams, a board supervisor who represents Mayersville, is skeptical the prison has kept its promise to Issaquena County. So is Willie Peterson, an alderman who has worked in local government for decades.

“We ain’t got no benefit from it, make sure you put that down,” Peterson said.

The prison recently has been at risk of shuttering. In 2019, the board of supervisors voted to do just that, believing the prison had lost more than $760,000 that year. But Williams thought there was more to the story. He’d been getting calls from people concerned the prison would be privatized, so he audited the numbers and determined the shortfall had simply been a mathematical error.

“I feel like, if something is not right, if it’s something that especially an interest group or anybody else have over the people, over the community, then I speak up,” Williams said.

With what money the county does have, Williams would much rather be spending his time on ambitious projects to finally develop Issaquena. In his nearly eight years as a supervisor, he has led the board to build a park and secured funding for a walking trail outside the county courthouse, right next to the street that could one day be Mayersville’s center of business activity.

But Williams wants to do more. He has a long list. To attract tourism, he wants to preserve the home of former Mayersville Mayor Unita Blackwell, the first Black woman to be elected mayor in the United States.

The Mississippi River, he says, is Mayersville’s “golden opportunity for economic development,” but the town doesn’t even have a port. He’d like to raise salaries at the prison, which pays just a few dollars above minimum wage. Issaquena, with its quiet swathes of land, attracts hundreds of recreational hunters and fishers — but there’s no place for them to buy gas locally.

The county’s future, Williams said, should be about “give and take” between landowners and workers.

“I benefit from the farmers,” said Williams, who started with his dad a local lawn business mowing farmers’ yards. “But as far as the people that just want a job here, they’re more likely gonna have to work on a farm or go 50 or 60 miles to get a job.”

Yet so many of his ideas require land to generate taxes and to build on. In recent years, some of the county’s land was bought by the state to create hunting grounds named after former governor Phil Bryant.

Change also requires political will. Some supervisors, like Eddie Hatcher, who runs a trucking company and privately owned hunting grounds, believe jobs are available in Issaquena if people want to work.

“When the government is giving able-bodies money for nothing,” he said, “why would you go to work?”

And sometimes even small improvements can be hard to do in an under-resourced place like Issaquena.

In late October, the Mayersville board of aldermen met at the town’s multipurpose complex. The mayor, Linda Williams Short, led the meeting. She has been mayor since she unseated Blackwell by 11 votes in 2001. Like most people in Issaquena, Williams Short doesn’t have a college degree.

Just two community members attended the meeting. The Yazoo City-bound Warren, whose mom is an alderman, and a man who Warren said always comes for “moral support.”

A heated discussion concerned some of the aging infrastructure in Mayersville, and the local construction company that was struggling to keep up. A few pipes were leaking across town. The water tower needed a new pump, and its gate, which had just been fixed, was falling down.

One alderman suggested getting “the whole system redone.” Williams Short insisted there was nothing she could do to speed up the work.

“We all know it’s been too long,” she said. “And all we can do is ask.”

This reporting is part of a collaboration with the Institute for Nonprofit News‘ Rural News Network, and the Cardinal News, KOSU, Mississippi Today, Shasta Scout and The Texas Tribune. Support from Ascendium made the project possible.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=310905

Mississippi Today

Mississippi prepares for another execution

The Mississippi Supreme Court has set the execution of a man who kidnapped and murdered a 20-year-old community college student in north Mississippi 30 years ago.

Charles Ray Crawford, 59, is set to be executed Oct. 15 at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, after multiple requests by the attorney general’s office.

Eight justices joined the majority opinion to set the execution, concluding that Crawford has exhausted all state and federal legal remedies. Mississippi Supreme Court Justice T. Kenneth Griffis Jr. wrote the Friday opinion. Justice David Sullivan did not participate.

However, Kristy Noble with the Mississippi Office of Capital Post-Conviction Counsel released a statement saying it will file another appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court.

“”Mr. Crawford’s inexperienced trial counsel conceded his guilt to the jury — against Mr.

Crawford’s timely and repeated objections,” Noble said in the statement. “Mr. Crawford told his counsel to pursue a not guilty verdict. Counsel did just the opposite, which is precisely what the U.S. Supreme Court says counsel cannot do,” Noble said in the statement.

“A trial like Mr. Crawford’s – one where counsel concedes guilt over his client’s express wishes – is essentially no trial at all.”

Last fall, Crawford’s attorneys asked the court not to set an execution date because he hadn’t exhausted appeal efforts in federal court to challenge a rape conviction that is not tied to his death sentence. In June, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to take up Crawford’s case.

A similar delay occurred a decade ago, when the AG’s office asked the court to reset Crawford’s execution date, but that was denied because efforts to appeal his unrelated rape conviction were still pending.

After each unsuccessful filing, the attorney general’s office asked the Mississippi Supreme Court to set Crawford’s execution date.

On Friday, the court also denied Crawford’s third petition for post-conviction relief and a request for oral argument. It accepted the state’s motion to dismiss the petition. Seven justices concurred and Justice Leslie King concurred in result only. Again, Justice Sullivan did not participate.

Crawford was convicted and sentenced to death in Lafayette County for the 1993 rape and murder of North Mississippi Community College student Kristy Ray.

Days before he was set to go to trial on separate aggravated assault and rape charges, he kidnapped Ray from her parents’ Tippah County home, leaving ransom notes. Crawford took Ray to an abandoned barn where he stabbed her, and his DNA was found on her, indicating he sexually assaulted her, according to court records.

Crawford told police he had blackouts and only remembered parts of the crime, but not killing Ray. Later he admitted “he must of killed her” and led police to Ray’s body, according to court records.

At his 1994 trial he presented an insanity defense, including that he suffered from psychogenic amnesia – periods of time lapse without memory. Medical experts who provided rebuttal testimony said Crawford didn’t have psychogenic amnesia and didn’t show evidence of bipolar illness.

The last person executed in Mississippi was Richard Jordan in June, previously the state’s oldest and longest serving person on death row.

There are 36 people on death row, according to records from the Mississippi Department of Corrections.

Update 9/15/25: This story has been updated to include a response from the Mississippi Office of Capital Post-Conviction Counsel

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Mississippi prepares for another execution appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

The article presents a factual and balanced account of the legal proceedings surrounding a scheduled execution in Mississippi. It includes perspectives from both the state’s attorney general’s office and the defense counsel, without using emotionally charged language or advocating for a particular political stance. The focus on legal details and court decisions reflects a neutral, informative approach typical of centrist reporting.

Mississippi Today

Presidents are taking longer to declare major natural disasters. For some, the wait is agonizing

TYLERTOWN — As an ominous storm approached Buddy Anthony’s one-story brick home, he took shelter in his new Ford F-250 pickup parked under a nearby carport.

Seconds later, a tornado tore apart Anthony’s home and damaged the truck while lifting it partly in the air. Anthony emerged unhurt. But he had to replace his vehicle with a used truck that became his home while waiting for President Donald Trump to issue a major disaster declaration so that federal money would be freed for individuals reeling from loss. That took weeks.

“You wake up in the truck and look out the windshield and see nothing. That’s hard. That’s hard to swallow,” Anthony said.

Disaster survivors are having to wait longer to get aid from the federal government, according to a new Associated Press analysis of decades of data. On average, it took less than two weeks for a governor’s request for a presidential disaster declaration to be granted in the 1990s and early 2000s. That rose to about three weeks during the past decade under presidents from both major parties. It’s taking more than a month, on average, during Trump’s current term, the AP found.

The delays mean individuals must wait to receive federal aid for daily living expenses, temporary lodging and home repairs. Delays in disaster declarations also can hamper recovery efforts by local officials uncertain whether they will receive federal reimbursement for cleaning up debris and rebuilding infrastructure. The AP collaborated with Mississippi Today and Mississippi Free Press on the effects of these delays for this report.

“The message that I get in the delay, particularly for the individual assistance, is that the federal government has turned its back on its own people,” said Bob Griffin, dean of the College of Emergency Preparedness, Homeland Security and Cybersecurity at the University at Albany in New York. “It’s a fundamental shift in the position of this country.”

The wait for disaster aid has grown as Trump remakes government

The Federal Emergency Management Agency often consults immediately with communities to coordinate their initial disaster response. But direct payments to individuals, nonprofits and local governments must wait for a major disaster declaration from the president, who first must receive a request from a state, territory or tribe. Major disaster declarations are intended only for the most damaging events that are beyond the resources of states and local governments.

Trump has approved more than two dozen major disaster declarations since taking office in January, with an average wait of almost 34 days after a request. That ranged from a one-day turnaround after July’s deadly flash flooding in Texas to a 67-day wait after a request for aid because of a Michigan ice storm. The average wait is up from a 24-day delay during his first term and is nearly four times as long as the average for former Republican President George H.W. Bush, whose term from 1989-1993 coincided with the implementation of a new federal law setting parameters for disaster determinations.

The delays have grown over time, regardless of the party in power. Former Democratic President Joe Biden, in his last year in office, averaged 26 days to declare major disasters — longer than any year under former Democratic President Barack Obama.

FEMA did not respond to the AP’s questions about what factors are contributing to the trend.

Others familiar with FEMA noted that its process for assessing and documenting natural disasters has become more complex over time. Disasters have also become more frequent and intense because of climate change, which is mostly caused by the burning of fuels such as gas, coal and oil.

The wait for disaster declarations has spiked as Trump’s administration undertakes an ambitious makeover of the federal government that has shed thousands of workers and reexamined the role of FEMA. A recently published letter from current and former FEMA employees warned the cuts could become debilitating if faced with a large-enough disaster. The letter also lamented that the Trump administration has stopped maintaining or removed long-term planning tools focused on extreme weather and disasters.

Shortly after taking office, Trump floated the idea of “getting rid” of FEMA, asserting: “It’s very bureaucratic, and it’s very slow.”

FEMA’s acting chief suggested more recently that states should shoulder more responsibility for disaster recovery, though FEMA thus far has continued to cover three-fourths of the costs of public assistance to local governments, as required under federal law. FEMA pays the full cost of its individual assistance.

Former FEMA Administrator Pete Gaynor, who served during Trump’s first term, said the delay in issuing major disaster declarations likely is related to a renewed focus on making sure the federal government isn’t paying for things state and local governments could handle.

“I think they’re probably giving those requests more scrutiny,” Gaynor said. “And I think it’s probably the right thing to do, because I think the (disaster) declaration process has become the ‘easy button’ for states.”

The Associated Press on Monday received a statement from White House spokeswoman Abigail Jackson in response to a question about why it is taking longer to issue major natural disaster declarations:

“President Trump provides a more thorough review of disaster declaration requests than any Administration has before him. Gone are the days of rubber stamping FEMA recommendations – that’s not a bug, that’s a feature. Under prior Administrations, FEMA’s outsized role created a bloated bureaucracy that disincentivized state investment in their own resilience. President Trump is committed to right-sizing the Federal government while empowering state and local governments by enabling them to better understand, plan for, and ultimately address the needs of their citizens. The Trump Administration has expeditiously provided assistance to disasters while ensuring taxpayer dollars are spent wisely to supplement state actions, not replace them.”

In Mississippi, frustration festered during wait for aid

The tornado that struck Anthony’s home in rural Tylertown on March 15 packed winds up to 140 mph. It was part of a powerful system that wrecked homes, businesses and lives across multiple states.

Mississippi’s governor requested a federal disaster declaration on April 1. Trump granted that request 50 days later, on May 21, while approving aid for both individuals and public entities.

On that same day, Trump also approved eight other major disaster declarations for storms, floods or fires in seven other states. In most cases, more than a month had passed since the request and about two months since the date of those disasters.

If a presidential declaration and federal money had come sooner, Anthony said he wouldn’t have needed to spend weeks sleeping in a truck before he could afford to rent the trailer where he is now living. His house was uninsured, Anthony said, and FEMA eventually gave him $30,000.

In nearby Jayess in Lawrence County, Dana Grimes had insurance but not enough to cover the full value of her damaged home. After the eventual federal declaration, Grimes said FEMA provided about $750 for emergency expenses, but she is now waiting for the agency to determine whether she can receive more.

“We couldn’t figure out why the president took so long to help people in this country,” Grimes said. “I just want to tie up strings and move on. But FEMA — I’m still fooling with FEMA.”

Jonathan Young said he gave up on applying for FEMA aid after the Tylertown tornado killed his 7-year-old son and destroyed their home. The process seemed too difficult, and federal officials wanted paperwork he didn’t have, Young said. He made ends meet by working for those cleaning up from the storm.

“It’s a therapy for me,” Young said, “to pick up the debris that took my son away from me.”

Historically, presidential disaster declarations containing individual assistance have been approved more quickly than those providing assistance only to public entities, according to the AP’s analysis. That remains the case under Trump, though declarations for both types are taking longer.

About half the major disaster declarations approved by Trump this year have included individual assistance.

Some people whose homes are damaged turn to shelters hosted by churches or local nonprofit organizations in the initial chaotic days after a disaster. Others stay with friends or family or go to a hotel, if they can afford it.

But some insist on staying in damaged homes, even if they are unsafe, said Chris Smith, who administered FEMA’s individual assistance division under three presidents from 2015-2022. If homes aren’t repaired properly, mold can grow, compounding the recovery challenges.

That’s why it’s critical for FEMA’s individual assistance to get approved quickly — ideally, within two weeks of a disaster, said Smith, who’s now a disaster consultant for governments and companies.

“You want to keep the people where they are living. You want to ensure those communities are going to continue to be viable and recover,” Smith said. “And the earlier that individual assistance can be delivered … the earlier recovery can start.”

In the periods waiting for declarations, the pressure falls on local officials and volunteers to care for victims and distribute supplies.

In Walthall County, where Tylertown is, insurance agent Les Lampton remembered watching the weather news as the first tornado missed his house by just an eighth of a mile. Lampton, who moonlights as a volunteer firefighter, navigated the collapsed trees in his yard and jumped into action. About 45 minutes later, the second tornado hit just a mile away.

“It was just chaos from there on out,” Lampton said.

Walthall County, with a population of about 14,000, hasn’t had a working tornado siren in about 30 years, Lampton said. He added there isn’t a public safe room in the area, although a lot of residents have ones in their home.

Rural areas with limited resources are hit hard by delays in receiving funds through FEMA’s public assistance program, which, unlike individual assistance, only reimburses local entities after their bills are paid. Long waits can stoke uncertainty and lead cost-conscious local officials to pause or scale-back their recovery efforts.

In Walthall County, officials initially spent about $700,000 cleaning up debris, then suspended the cleanup for more than a month because they couldn’t afford to spend more without assurance they would receive federal reimbursement, said county emergency manager Royce McKee. Meanwhile, rubble from splintered trees and shattered homes remained piled along the roadside, creating unsafe obstacles for motorists and habitat for snakes and rodents.

When it received the federal declaration, Walthall County took out a multimillion-dollar loan to pay contractors to resume the cleanup.

“We’re going to pay interest and pay that money back until FEMA pays us,” said Byran Martin, an elected county supervisor. “We’re hopeful that we’ll get some money by the first of the year, but people are telling us that it could be [longer].”

Lampton, who took after his father when he joined the volunteer firefighters 40 years ago, lauded the support of outside groups such as Cajun Navy, Eight Days of Hope, Samaritan’s Purse and others. That’s not to mention the neighbors who brought their own skid steers and power saws to help clear trees and other debris, he added.

“That’s the only thing that got us through this storm, neighbors helping neighbors,” Lampton said. “If we waited on the government, we were going to be in bad shape.”

Lieb reported from Jefferson City, Missouri, and Wildeman from Hartford, Connecticut.

Update 98/25: This story has been updated to include a White House statement released after publication.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Presidents are taking longer to declare major natural disasters. For some, the wait is agonizing appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a critical view of the Trump administration’s handling of disaster declarations, highlighting delays and their negative impacts on affected individuals and communities. It emphasizes concerns about government downsizing and reduced federal support, themes often associated with center-left perspectives that favor robust government intervention and social safety nets. However, it also includes statements from Trump administration officials defending their approach, providing some balance. Overall, the tone and framing lean slightly left of center without being overtly partisan.

Mississippi Today

Northeast Mississippi speaker and worm farmer played key role in Coast recovery after Hurricane Katrina

The 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina slamming the Mississippi Gulf Coast has come and gone, rightfully garnering considerable media attention.

But still undercovered in the 20th anniversary saga of the storm that made landfall on Aug. 29, 2005, and caused unprecedented destruction is the role that a worm farmer from northeast Mississippi played in helping to revitalize the Coast.

House Speaker Billy McCoy, who died in 2019, was a worm farmer from the Prentiss, not Alcorn County, side of Rienzi — about as far away from the Gulf Coast as one could be in Mississippi.

McCoy grew other crops, but a staple of his operations was worm farming.

Early after the storm, the House speaker made a point of touring the Coast and visiting as many of the House members who lived on the Coast as he could to check on them.

But it was his action in the forum he loved the most — the Mississippi House — that is credited with being key to the Coast’s recovery.

Gov. Haley Barbour had called a special session about a month after the storm to take up multiple issues related to Katrina and the Gulf Coast’s survival and revitalization. The issue that received the most attention was Barbour’s proposal to remove the requirement that the casinos on the Coast be floating in the Mississippi Sound.

Katrina wreaked havoc on the floating casinos, and many operators said they would not rebuild if their casinos had to be in the Gulf waters. That was a crucial issue since the casinos were a major economic engine on the Coast, employing an estimated 30,000 in direct and indirect jobs.

It is difficult to fathom now the controversy surrounding Barbour’s proposal to allow the casinos to locate on land next to the water. Mississippi’s casino industry that was birthed with the early 1990s legislation was still new and controversial.

Various religious groups and others had continued to fight and oppose the casino industry and had made opposition to the expansion of gambling a priority.

Opposition to casinos and expansion of casinos was believed to be especially strong in rural areas, like those found in McCoy’s beloved northeast Mississippi. It was many of those rural areas that were the homes to rural white Democrats — now all but extinct in the Legislature but at the time still a force in the House.

So, voting in favor of casino expansion had the potential of being costly for what was McCoy’s base of power: the rural white Democrats.

Couple that with the fact that the Democratic-controlled House had been at odds with the Republican Barbour on multiple issues ranging from education funding to health care since Barbour was inaugurated in January 2004.

Barbour set records for the number of special sessions called by the governor. Those special sessions often were called to try to force the Democratic-controlled House to pass legislation it killed during the regular session.

The September 2005 special session was Barbour’s fifth of the year. For context, current Gov. Tate Reeves has called four in his nearly six years as governor.

There was little reason to expect McCoy to do Barbour’s bidding and lead the effort in the Legislature to pass his most controversial proposal: expanding casino gambling.

But when Barbour ally Lt. Gov. Amy Tuck, who presided over the Senate, refused to take up the controversial bill, Barbour was forced to turn to McCoy.

The former governor wrote about the circumstances in an essay he penned on the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina for Mississippi Today Ideas.

“The Senate leadership, all Republicans, did not want to go first in passing the onshore casino law,” Barbour wrote. “So, I had to ask Speaker McCoy to allow it to come to the House floor and pass. He realized he should put the Coast and the state’s interests first. He did so, and the bill passed 61-53, with McCoy voting no.

“I will always admire Speaker McCoy, often my nemesis, for his integrity in putting the state first.”

Incidentally, former Rep. Bill Miles of Fulton, also in northeast Mississippi, was tasked by McCoy with counting, not whipping votes, to see if there was enough support in the House to pass the proposal. Not soon before the key vote, Miles said years later, he went to McCoy and told him there were more than enough votes to pass the legislation so he was voting no and broached the idea of the speaker also voting no.

It is likely that McCoy would have voted for the bill if his vote was needed.

Despite his no vote, the Biloxi Sun Herald newspaper ran a large photo of McCoy and hailed the Rienzi worm farmer as a hero for the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Northeast Mississippi speaker and worm farmer played key role in Coast recovery after Hurricane Katrina appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

The article presents a factual and balanced account of the political dynamics surrounding Hurricane Katrina recovery efforts in Mississippi, focusing on bipartisan cooperation between Democratic and Republican leaders. It highlights the complexities of legislative decisions without overtly favoring one party or ideology, reflecting a neutral and informative tone typical of centrist reporting.

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

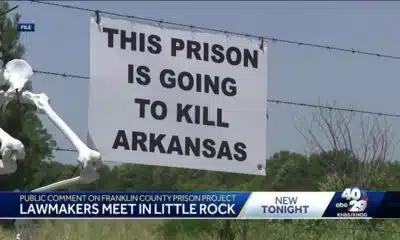

Group in lawsuit say Franklin county prison land was bought before it was inspected

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days ago

Lexington man accused of carjacking, firing gun during police chase faces federal firearm charge

-

The Center Square6 days ago

California mother says daughter killed herself after being transitioned by school | California

-

Mississippi News Video7 days ago

Carly Gregg convicted of all charges

-

Mississippi News Video7 days ago

2025 Mississippi Book Festival announces sponsorship

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

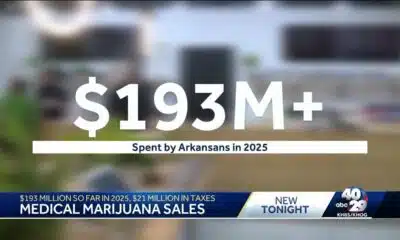

Arkansas medical marijuana sales on pace for record year

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

Zaxby's Player of the Week: Dylan Jackson, Vigor WR

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed6 days ago

Local, statewide officials react to Charlie Kirk death after shooting in Utah