Mississippi Today

In the state with the most C-sections, these hospitals are challenging the status quo

This is the second story of a two-part series. Read the first story here.

Three hospitals with some of the lowest use of low-risk C-sections in Mississippi vary in almost every way — location, size and the type of providers who deliver babies.

Wayne General is a small, rural hometown hospital in eastern Mississippi. Baptist DeSoto is a large regional hospital just outside of Memphis. And Singing River is a mid-size hospital network on the Gulf Coast that boasts low rates at all three of its delivery locations.

But the providers at these hospitals all agree on one thing: birth takes time.

Their hospitals rank at the top for lowest rates of a particular kind of C-section referred to in the medical world as NTSV — which stands for nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex — meaning those occurring in first-time mothers who are full-term and having a single baby in the head-down position. These C-sections are often described as “low-risk cesareans.”

“I think we’ve all been rewarded by mamas who progressed, who we maybe didn’t think would, just by virtue of giving them more time,” said certified nurse midwife Cynthia Odom, who has worked at Wayne General in Waynesboro for 30 years.

It’s rare enough to have a midwife on staff at a hospital in Mississippi, which has no midwifery certification programs after the University of Mississippi Medical Center terminated its program in the 1970s due to a lack of funding and support from physicians. But Wayne General is also one of only two hospitals in the state that uses family physicians trained in obstetrics in place of OB-GYNs — a workaround to the state’s severe shortage of these doctors.

Before they were joined by Dr. Allison Akridge in September, Odom and Dr. Kelvin Sherman worked side by side for decades, delivering all the babies in Wayne County — and even some from maternity care deserts across the border in Alabama.

Odom and Akridge joked that every once in a while, they catch a video of Sherman running across the street from his house to the hospital for a delivery and it makes the rounds on social media.

“I think a lot of it has just been how available Dr. Sherman and Cynthia have been to our patients for years now,” Akridge said. “I mean, this has been their whole life, taking care of the pregnant population here.”

The hospital’s unique obstetric team has translated into a uniquely low use of C-sections. In 2022, just 14.3% of moms at low risk for a C-section received the surgery.

“You look at a vaginal delivery versus a C-section, there’s just more factors that can go wrong,” Sherman said. “Even though it’s never been safer to have a C-section in the history of mankind than it is now, we still try to strive for a routine vaginal delivery. And we give patients long enough in their labor.”

While many hospitals won’t let women go past 40 or 41 weeks of pregnancy and insist on a medical induction before then, Wayne General allows women to go up to 42 weeks — about two weeks past the typical due date — if they choose to.

Although a due date is only an estimate of when a baby will come, the risks of adverse outcomes increase the longer a woman goes past 40 weeks.

Part of what makes the team at Wayne General feel confident in the care they provide is the fact that they know their patients so well. They take care of patients well before pregnancy and long after birth for parents and baby.

“You know them, you have a good relationship with them and you’re just more patient, you’re really in tune with their history and their prenatal care, and it makes you less anxious about their care when you’ve been so hands-on with them,” explained Akridge.

Midwifery care has long been associated with improved outcomes, including a decreased chance of cesarean birth. But at Wayne General, what makes the midwifery model of care especially effective is the harmony between providers.

“I think there’s some midwife in my docs, and I think there’s some medicine in this midwife,” Odom said.

These three hospitals with some of the lowest use of C-sections in the state all utilize a reinvented midwifery technique called Spinning Babies, which allows laboring mothers to change positions on the bed even when an epidural may keep them from moving off the bed.

“It sounds kind of crazy, but really what it is about is getting the body into positions that open the pelvis and allow the baby to descend,” explained Lori Weimer, patient care manager in the labor and delivery unit at Singing River. “So, that prevents a lot of — especially [low-risk] — C-sections, where we just need to give that body some encouragement.”

Singing River has also implemented a program called “Team Birth,” where every mother delivering at the hospital gets to meet with her doctor and nurse to discuss her ideal birth plan, which providers try their best to follow. In the majority of cases, Weimer said, that’s possible.

“Labor is not a sickness, it’s not an illness,” said Weimer. “It’s a natural thing.”

Variation in low-risk C-sections from year to year is normal — and even good, because it suggests that the procedure follows individual needs, not routine or culture.

“We don’t like to focus on a number, because if you’re not hitting that number, it makes you feel like you may be doing something wrong. Our goal is to have a healthy mom and a healthy baby,” Dr. Harvey Mason, chief medical officer at Baptist DeSoto said. “We want to create the culture here at DeSoto that the expectation when a [first-time, low-risk] mom comes into the hospital is that we’re going to do everything we can to have a successful vaginal delivery.”

Today, nearly a third of deliveries use inductions — either medical or elective — to kickstart labor before it begins on its own. Elective inductions are those performed for non-medical reasons, due to provider or patient preference.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends no elective inductions before 39 weeks.

Baptist DeSoto plans to go one step further and ban elective inductions before 40 weeks in 2025.

Dr. Alok Kumar, an OB-GYN at the hospital, emphasized the importance of choosing the right candidates for elective inductions and educating patients on the risks a failed induction can have.

“It’s really important for us as physicians to guide a patient and say, ‘Okay, an induction before your body is ready is not necessarily the best thing and can significantly increase your risk of a C-section,’” he explained.

Whether elective inductions lead to more cesareans is a contested issue among doctors, explained Gene Declercq, the Boston professor whose research focuses on maternal mortality and morbidity.

“People feel strongly on both sides of that,” he said. “Some say you can do an induction to avoid a cesarean, and result in a vaginal birth. And others say, well, but failed inductions lead to cesareans.”

The research is still inconclusive. Much of the contention comes down to the interpretation of a study that came out in 2018 and suggested elective inductions in the 39th week decrease one’s chances of a C-section. But the study, called the ARRIVE trial, has been criticized for its methodology, Declercq explained.

Allison Doyle, the new midwife hired at Northwest Regional Medical Center, says that one study isn’t enough to warrant the pervasiveness of elective 39-week inductions in low-risk, first-time moms today.

“Throughout medical history, we’ve never changed our medical practice based on one study,” Doyle said. “And so I have a little bit of an issue with that, for one. Normally, it takes us 20 years and repeated studies, and you want those same outcomes repeated multiple times before you adjust.”

Solutions within reach: VBACs, midwives and culture

Being in a supportive environment is the best way to prevent an unnecessary C-section — and that goes for patients as well as doctors.

For patients, support can take the form of hands-on care with techniques such as Spinning Babies, emotional support from a doula, and being included in the decision-making process with doctors.

For doctors, support can look like a collaborative hospital culture where informed consent is incentivized and doctors receive the time they need to get to know patients, as well as guidance on how to better weigh risks and benefits.

But change will need to be systemic, experts say, and will need to address underlying health conditions that have made patients in the state more prone to undergoing surgical birth.

Doctors in the Delta say that the health conditions that plague the region contribute to a justifiably higher number of cesareans. But even for them, Mississippi’s number is too high.

“It’s truly hard for me to say what the right number of C-sections would be,” said Dr. Nina Ragunanthan, an OB-GYN who works at Bolivar Medical Center in Cleveland. “ … It does still feel a little higher here than an ideal level. However, I also still do think it makes sense that Mississippi does have higher rates of C-sections than other states.”

These health conditions, such as diabetes, obesity and hypertension, are a result of decades of low social determinants that have weighed on the region, in tandem with a lack of investment in the health landscape of the state.

“To achieve a lower C-section rate across the state, we need to address the underlying factors that raise that rate so much,” Ragunanthan said. “That means increasing the OB-GYN and midwife workforce to improve access to quality prenatal care, increasing the number of hospitals that can safely offer VBACs, and absolutely focusing on the underlying risk factors of obesity, hypertension, and diabetes that make C-sections more likely.”

There is renewed interest in addressing C-sections in Mississippi, though potential solutions like increasing midwifery care still face legislative hurdles.

On a Monday afternoon in late November, the Senate Study Group for Women, Children and Families held a six-hour meeting at the State Capitol in Jackson to hear from health care experts about priorities ahead of the 2025 legislative session.

Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann formed the group in 2022 following the Dobbs Supreme Court decision that overturned the constitutional right to an abortion.

Two speakers mentioned pervasive low-risk C-sections as a pressing issue. Dr. Catherine Brett, clinical medical director at the Mississippi Division of Medicaid, and Janice Scaggs, a certified nurse midwife at University of Mississippi Medical Center, both reiterated how the state’s pervasive surgeries contribute to poor health outcomes for mothers in the state.

Scaggs explained to lawmakers that the first-time population of women should be having the highest number of vaginal deliveries. Performing a cesarean affects not only that birth, but subsequent births, as well as the long-term health of the mother.

To keep C-sections low in this group of women, Scaggs recommended involving midwives in hospital birth.

“If we can support normal, healthy, term women with one baby head down —it’s the perfect population for midwives who are high-touch, lower-intervention, and only using intervention when necessary,” she said.

Scaggs was talking about certified midwives, of which there are several types, including certified professional midwives and certified nurse midwives. In Mississippi, which has no midwifery certification programs, anyone can call themselves a professional midwife, but very few certified midwives exist.

In the last decade, lawmakers have proposed bills aiming to shore up midwifery care in the state — with no success. A bill that would license professional midwives – and hopefully increase the number of them – is currently pending in the Legislature.

Mississippi has a long way to go in moving the needle on social determinants, health risks and a reliance on surgical birth. But in the meantime, doctors have the opportunity to shift the way they work with patients who have had prior C-sections.

Once a primary C-section has been done, the best thing doctors can do is support vaginal births for later pregnancies in women for whom it’s safe to do so, Scaggs said. These are referred to as vaginal birth after cesarean, or VBAC, and Mississippi has the lowest rate of these deliveries in the country.

Dr. Amber Shiflett, an OB-GYN at the University of Mississippi Medical Center and known to moms in the greater Jackson area as “the VBAC queen,” stressed the importance of picking the right candidates. That’s because while VBACs in the right patients reduce morbidity and mortality, they can be catastrophic when performed on the wrong candidates.

“Babies do best after a successful vaginal birth after C-section, but then the next best neonatal outcome is just with a repeat C-section, and then the third on the list is a failed trial of labor after C-section,” or letting a mom labor with the goal of a vaginal birth but ending up with a C-section.

Mothers who don’t make good candidates for a VBAC are: those who had their first C-section due to a condition that is likely to recur; are older; have had multiple C-sections; or are pregnant with multiple babies, she explained.

Those who are most likely to be successful are mothers who had a first C-section due to a problem that is unlikely to recur, are under 35, only had one former C-section and are pregnant with one baby. The incision of the first C-section also matters — those who had a low incision can more easily have a successful vaginal birth than those who had a higher incision.

In October, Jennifer Sloan-Ziegler — the Ridgeland mom who underwent a low-risk C-section in 2020 – gave birth to her second child with a VBAC at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. Several medical students crowded around her in the delivery room – they wanted to witness the VBAC because they had never seen one before, she said.

Sloan-Ziegler says she was resigned to the fact that she might need to have another C-section. The biggest difference for her between her two births was the way she was included in the decision-making process during her second birth. She had a doula present throughout her labor, and she had long discussions with her care team about her treatment at every turn.

Following her first traumatic birth, Sloan-Ziegler blamed herself.

“I was so angry at myself, and it took a long time to realize that yes, there were things I could have done differently, but ultimately the reason I was feeling the way that I was feeling was because I was so disempowered in that whole situation,” she reflected.

Her postpartum experience has been worlds smoother and easier this time around, she says.

“Changing the language from ‘This is what we’re doing’ to ‘This is what we’d like to recommend’ … even that small tweak in language makes a huge difference in how a woman feels her opinion is being respected,” she said.

This series is the result of a collaborative reporting partnership between Mississippi Today and The Fuller Project.

Mississippi Today, winner of the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for Local Reporting, is the state’s flagship nonprofit newsroom whose mission is to hold the powerful accountable and equip Mississippians with the news and information they need to understand and engage with their state.

The Fuller Project is an award-winning global nonprofit newsroom dedicated to reporting on issues that affect women. The Fuller Project encourages you to follow them and sign up to learn more.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

Rolling Fork – 2 Years Later

Tracy Harden stood outside her Chuck’s Dairy Bar in Rolling Fork, teary eyed, remembering not the EF-4 tornado that nearly wiped the town off the map two years before. Instead, she became emotional, “even after all this time,” she said, thinking of the overwhelming help people who’d come from all over selflessly offered.

“We’re back now, she said, smiling. “People have been so kind.”

“I stepped out of that cooler two years ago and saw everything, and I mean, everything was just… gone,” she said, her voice trailing off. “My God, I thought. What are we going to do now? But people came and were so giving. It’s remarkable, and such a blessing.”

“And to have another one come on almost the exact date the first came,” she said, shaking her head. “I got word from these young storm chasers I’d met. He told me they were tracking this one, and it looked like it was coming straight for us in Rolling Fork.”

“I got up and went outside.”

“And there it was!”

“I cannot tell you what went through me seeing that tornado form in the sky.”

The tornado that touched down in Rolling Fork last Sunday did minimal damage and claimed no lives.

Horns honk as people travel along U.S. 61. Harden smiles and waves.

She heads back into her restaurant after chatting with friends to resume grill duties as people, some local, some just passing through town, line up for burgers and ice cream treats.

Rolling Fork is mending, slowly. Although there is evidence of some rebuilding such as new homes under construction, many buildings like the library and post office remain boarded up and closed. A brutal reminder of that fateful evening two years ago.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

Remembering Big George Foreman and a poor guy named Pedro

George Foreman, surely one of the world’s most intriguing and transformative sports figures of the 20th century, died over the weekend at the age of 76. Please indulge me a few memories.

This was back when professional boxing was in its heyday. Muhammad Ali was heavyweight champion of the world for a second time. The lower weight divisions featured such skilled champions and future champs as Alex Arugello, Roberto “Hands of Stone” Duran, Tommy “Hit Man” Hearns and Sugar Ray Leonard.

Boxing was front page news all over the globe. Indeed, Ali was said to be the most famous person in the world and had stunned the boxing world by stopping the previously undefeated Foreman in an eighth round knockout in Kinshasa, Zaire, in October of 1974. Foreman, once an Olympic gold medalist at age 19, had won his previous 40 professional fights and few had lasted past the second round. Big George, as he was known, packed a fearsome punch.

My dealings with Foreman began in January of 1977, roughly 27 months after his Ali debacle with Foreman in the middle of a boxing comeback. At the time, I was the sports editor of my hometown newspaper in Hattiesburg when the news came that Foreman was going to fight a Puerto Rican professional named Pedro Agosto in Pensacola, just three hours away.

Right away, I applied for press credentials and was rewarded with a ringside seats at the Pensacola Civic Center. I thought I was going to cover a boxing match. It turned out more like an execution.

The mismatch was evident from the pre-fight introductions. Foreman towered over the 5-foot, 11-inch Agosto. Foreman had muscles on top of muscles, Agosto not so much. When they announced Agosto weighed 205 pounds, the New York sports writer next to me wise-cracked, “Yeah, well what is he going to weigh without his head?”

It looked entirely possible we might learn.

Foreman toyed with the smaller man for three rounds, almost like a full-grown German shepherd dealing with a tiny, yapping Shih Tzu. By the fourth round, Big George had tired of the yapping. With punches that landed like claps of thunder, Foreman knocked Agosto down three times. Twice, Agosto struggled to his feet after the referee counted to nine. Nearly half a century later I have no idea why Agosto got up. Nobody present– or the national TV audience – would have blamed him for playing possum. But, no, he got up the second time and stumbled over into the corner of the ring right in front of me. And that’s where he was when Foreman hit him with an evil right uppercut to the jaw that lifted the smaller man a foot off the canvas and sprayed me and everyone in the vicinity with Agosto’s blood, sweat and snot – thankfully, no brains. That’s when the ref ended it.

It remains the only time in my sports writing career I had to buy a T-shirt at the event to wear home.

So, now, let’s move ahead 18 years to July of 1995. Foreman had long since completed his comeback by winning back the heavyweight championship. He had become a preacher. He also had become a pitch man for a an indoor grill that bore his name and would sell more than 100 million units. He was a millionaire many times over. He made far more for hawking that grill than he ever made as a fighter. He had become a beloved figure, known for his warm smile and his soothing voice. And now he was coming to Jackson to sign his biography. His publishing company called my office to ask if I’d like an interview. I said I surely would.

One day at the office, I answered my phone and the familiar voice on the other end said, “This is George Foreman and I heard you wanted to talk to me.”

I told him I wanted to talk to him about his book but first I wanted to tell him he owed me a shirt.

“A shirt?” he said. “How’s that?”

I asked him if remembered a guy named Pedro Agosto. He said he did. “Man, I really hit that poor guy,” he said.

I thought you had killed him, I said, and I then told him about all the blood and snot that ruined my shirt.

“Man, I’m sorry about that,” he said. “I’d never hit a guy like that now. I was an angry, angry man back then.”

We had a nice conversation. He told me about finding his Lord. He told me about his 12 children, including five boys, all of whom he named George.

I asked him why he would give five boys the same name.

“I never met my father until late in his life,” Big George told me. “My father never gave me nothing. So I decided I was going to give all my boys something to remember me by. I gave them all my name.”

Yes, and he named one of his girls Georgette.

We did get around to talking about his book, and you will not be surprised by its title: “By George.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

://mississippitoday.org”>Mississippi Today.

Mississippi Today

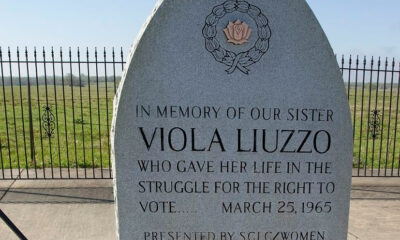

On this day in 1965

March 25, 1965

Viola Gregg Liuzzo stood among the crowd of 25,000 gathered outside Alabama’s state Capitol in Montgomery, some of whom had been beaten and tear-gassed by state troopers after crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma.

The Detroit mother of five wept as she watched that “Bloody Sunday” broadcast on the evening news. Afterward, she heard and responded to Martin Luther King Jr.’s call to join the march for voting rights for all Americans.

“[We’re] going to change the world,” she vowed. “One day they’ll write about us. You’ll see.”

Now she listened as King spoke to the crowd.

“The burning of our churches will not deter us,” he said. “The bombing of our homes will not dissuade us. We are on the move now.” To those who asked, “How long?” King replied, “Not long, because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

After King finished, she was helping drive marchers back to Selma when Klansmen sped after her. She floored her car, singing, “We Shall Overcome,” as Klansmen shot into her car 14 times, killing her.

Two Klansmen were convicted of federal conspiracy charges and given maximum sentences of 10 years. King and Liuzzo are among 40 martyrs listed on the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery. A Selma Memorial plaque now honors her and two others killed in the protest, and a statue of her now stands in Detroit, honoring her courage.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed5 days agoSaying it’s ‘about hate,’ Beshear vetoes ban on DEI in Kentucky public higher education

-

Local News Video23 hours ago

Local News Video23 hours agoLocal pharmacists advocating for passage of bill limiting control of pharmacy benefit managers

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days agoSurvivors speak out ahead of Oklahoma inmate’s scheduled execution

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days agoWoman accused of stabbing neighbor's dog to death | FOX 5 News

-

News from the South - South Carolina News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - South Carolina News Feed7 days agoResidents question Georgetown Co. plan for low-density development on golf courses

-

News from the South - South Carolina News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - South Carolina News Feed6 days ago'Cold-blooded murder:' New filed court documents released for Marion man charged in OIS

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed3 days agoI-35 crash: Witness confronts driver who caused deadly crash

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed2 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed2 days agoDeSantis returns millions in federal funds as Florida cities receive DOGE letters