Mississippi Today

In the heart of a stretch of southwest Mississippi sits Prospect Hill, a link to the past that stretches across the globe

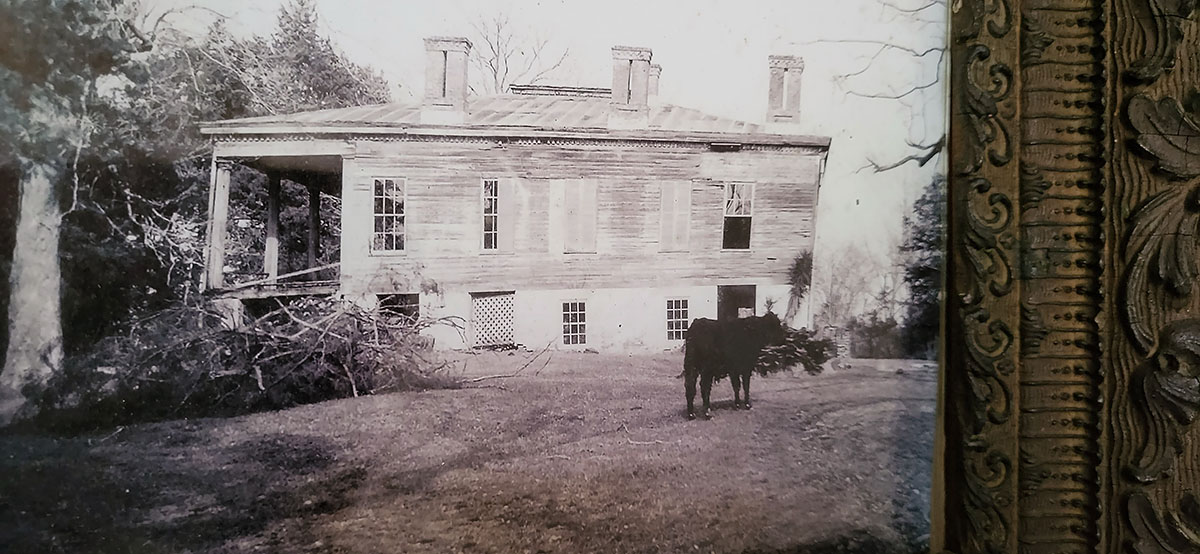

Prospect Hill, a preserved, abandoned building hidden deep in the woods of Jefferson County, Mississippi, is a connection to the history of Liberia in West Africa and to the lives of descendant communities of over 300 enslaved-ancestors from Mississippi.

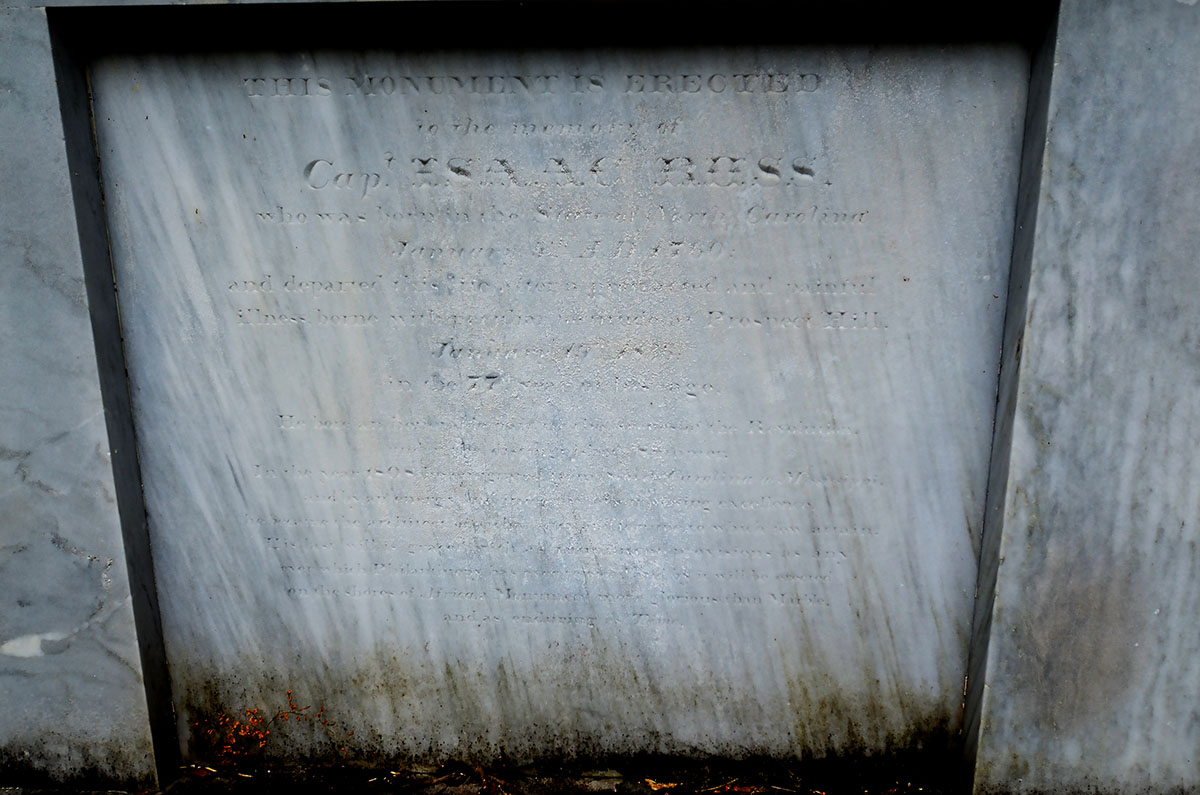

Former slaves of Capt. Isaac Ross established the Liberian colony known as “Mississippi-in-Africa”, as called for in his will.

Shawn Lambert, assistant professor of anthropology at Mississippi State University, began an excavation of the site June 18, assisted by James Andrew Whitaker, a cultural anthropologist.

A foundation in the ground adjacent to the big house, barely noticeable, is the primary focus during this first broad excavation. Lambert and Whitaker believe many of the enslaved people worked and lived in what could be a dependency, or kitchen house.

With help from participants from the public, they unearthed evidence on the 23.3 acres dating around the early 1800s to late 1800s supporting their hypothesis about the lives and cultural activity: gunflints, chunks of rock used to generate sparks to ignite gunpowder; leadshots, originally used in muskets and early rifles; a 4- to 7-inch knife-blade; dark, rich green fragments possibly from a wine bottle, white pieces from a ceramic plate, and cut (tapered-rectangular) and square (hand-forged) nails.

“These artifacts don’t just provide insight into the daily lives of the people who lived and the tools utilized in their world, but the environment and landscape of how they interacted with each other,” Lambert told Mississippi Today.

Lambert and Whitaker began the archaeological excavation of the Lorman plantation site to understand how aspects of material and social culture from the slaves’ lives in Mississippi were carried through this transAtlantic reverse migration.

As leader of the excavation, Lambert taught the participants archaeological methods and ethical archaeology to have a more “holistic narrative” of what occurred at Prospect Hill.

Nikki Mattson, a Southeast field representative for the Archaeological Conservancy, participated in the dig because she came across the book “Mississippi in Africa” by Alan Huffman around 15 years ago. She said she was at a place and time in her life where she was questioning a lot of the “deep inherent things” she was taught growing up in the Mississippi Delta, and the book was a pivotal moment for her.

After gaining her master’s degree in archaeology, she applied to the conservancy and found that it owned that property. Mattson said she takes any chance to be involved seriously.

“Even though these artifacts might seem kind of insignificant, little things to some people, it’s really huge,” Mattson explained. “It’s all these little pieces of a bigger story, and that’s exciting.”

Finding materials at the site and combining them with historical records to gain a better understanding of the past, while providing a learning experience, Lambert said.

“I think working at this site and working with the descendant communities can have a positive effect on people who come and work. (We can) realize the history and acknowledge the history that has gone on here,” Lambert said.

He said he believes this type of fieldwork can educate people statewide. By looking at the shapes, colors and textures of found artifacts, he can uncover the history of a place and reveal aspects of life that would otherwise be lost.

“I think archaeology is a powerful tool (that allows us) to talk about history and a history that maybe Mississippi doesn’t talk about a lot,” Lambert explained, “our history of enslavement.”

Whitaker, a cultural anthropologist, began his research in West Africa and talked with descendants and some indigenous people not related to the Mississippi settlers.

This summer, he conducted 12 interviews in Liberia, along with 52 last summer in Monrovia and different locations of Sinoe County, Liberia, (the capital of Greenville, Louisiana and Lexington). His research inspired the idea for this excavation.

“This kind of research uncovers aspects about settlement and the history of Liberia as it relates to the United States,” Whitaker continued, “and also as it precedes those interactions with the United States by a long time.”

Whitaker said he and Lambert are attempting to trace this cultural movement, through this collaborative project with the Archaeological Conservancy and the descendant communities of the enslaved ancestors along with grants funded by the Mississippi Humanities Council and Mississippi State University Global Grant.

“We want to understand more about the lives of the people who never went to Liberia and also the ones who later became the first American LIberian settlers.” Whitaker said. “We’re hoping to follow up this excavation with a second one, maybe one or two years from now, to map the material culture in Mississippi to the material culture in Liberia.”

Through this mapping, they aim to uncover aspects of ancestors’ lives in Mississippi that were carried with them and trace the changes in the social lives of those same people.

“I think using the power of archaeology to connect the past with today is powerful,” Lambert said. “This is the beginning of what could be something a lot larger and much more special for research and this community.”

The excavation continues through June 28.

Revolutionary War veteran Capt. Issac Ross founded Prospect Hill in the woods of former Mississippi Territory around 1808.

Traveling from South Carolina to Jefferson County, Mississippi, Ross brought hundreds of slaves and freed Black people he served with in the Revolutionary War.

Soon, his accumulated wealth allowed him access to more acreage and slaves. He allowed his slaves to read and write, illegal at the time in Mississippi. They also learned skills and trades.

When Ross prepared his will in 1834, he stipulated that his plantation should be sold and the proceeds used to pay for his slaves’ passage to the newly established colony of Liberia in western Africa formed by a branch of the American Colonization Society, the Mississippi Colonization Society, of which he was a member.

He didn’t want families separated, and those who remained at the plantation would work for pay and be considered free men. The will stipulated his plans would be set in motion once his daughter, Margaret Allison Reed, passed away. Ross died two years after the will was drawn up, and Reed shortly after in 1838.

It was left to Isaac Ross Wade, son of Jane Brown Ross (one of Capt. Ross’ three daughters) and the executor of the will, to uphold the will’s provisions. Instead, Wade contested the will’s legitimacy for more than a decade.

He stopped the slaves from gaining their freedom, leading to a revolt. The mansion burned to the ground in April 1846 under alleged suspicious circumstances, taking the life of a 6-year-old girl. Overseers, hearing rumors of the slaves’ plot to kill the family, lynched at least 11 slaves believed to be involved.

A few months later, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Ross’s will. About 120 of Ross’ 160 slaves left for Africa, while the others remained in Jefferson County as slaves. In total, the coalition society arranged for 300 free ex-slaves to travel to Africa.

The plantation house was finally sold in 1848, but the African colony received none of the proceeds. The house returned to Wade’s possession in 1850, and he built the present-day house there in 1854.

The home survived the Civil War and Wade’s death in 1891. After Wade’s death, his brother Battaille Harrison “BH” Wade retained ownership of the house. From 1956 onward, descendants of those enslaved occupied the house. And in 1968, others occupied the site until it became unlivable through neglect.

It wasn’t until 2011 when the Archaeological Conservancy acquired the property that the preservation of the historical site started.

The existence of this rare Mississippi plantation site spans over two continents and over 200 years, with history embedded in its grounds.

“We know a lot about what went on inside the big house. It’s the other side of the story we want to know (such as) the enslaved people who built it and kept it running and the people who have ties to it,” Jessica Crawford, the Southeast Regional director of the Archaeological Conservancy, told Mississippi Today.

The Archaeological Conservancy primarily works on archaeological evidence buried in the ground. However, Crawford convinced her board of directors to consider Prospect Hill because of the site’s significant history.

As of 2023, Crawford said she is talking to architects to draw a blueprint to preserve the house. She also talked to a private donor who is willing to pay for the proposed plan.

“There’s a lot of work that needs to be done to keep it standing. I don’t know specifically where we will start yet,” Crawford said.

Parts of the house are rotting from previous rains. Plaster on the walls is cracking and falling onto the rotten wooden floor, making it dangerous to walk on. The original porch has not been rebuilt. Termites are eating away at newly constructed wood. In addition, the site lacks water due to lack of community water in the rural area.

“We don’t plan to restore it to some grand plantation house. We want floors so it’s better and safer to walk on,” Crawford explained. “We eventually hope to use it for things like public archaeology events, like this one, and public outreach events like an open house.”

In 2012, one year after the Archaeological Conservancy acquired the site and 3.1 acres, the organization acquired an additional 20 acres. There were many projects to focus on, but replacing the roof was a major concern. The 2017 roof installation was a critical step in preserving the home’s flooring.

“I used to have probably 25 kiddie swimming pools in there catching water every time it rained and that roof absolutely saved it,” Crawford continued. “It’s still dry when it rains, and it wasn’t (dry) for a long time.”

Crawford raised money through donations and grants separate from the organization’s regular funding sources to pay for the new roofing and stabilization of the roofing, which cost $114,611.

The Conservancy obtained a $50,000 emergency preservation grant from the Mississippi Department of Archives and History and raised additional needed capital from donations.

“This place was saved from falling on the ground by a bunch of people. It wasn’t just me, it was a lot of people who cared and came out and gave money and gave time. People volunteered out there so much,” Crawford told Mississippi Today.

“The story of this place is a small picture of what the larger world around us is like. There are a lot of stories there that need to be told. (The enslaved people) names should be known.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Hospitals see danger in Medicaid spending cuts

Mississippi hospitals could lose up to $1 billion over the next decade under the sweeping, multitrillion-dollar tax and policy bill President Donald Trump signed into law last week, according to leaders at the Mississippi Hospital Association.

The leaders say the cuts could force some already-struggling rural hospitals to reduce services or close their doors.

The law includes the largest reduction in federal health and social safety net programs in history. It passed 218-214, with all Democrats voting against the measure and all but five Republicans voting for it.

In the short term, these cuts will make health care less accessible to poor Mississippians by making the eligibility requirements for Medicaid insurance stiffer, likely increasing people’s medical debt.

In the long run, the cuts could lead to worsening chronic health conditions such as diabetes and obesity for which Mississippi already leads the nation, and making private insurance more expensive for many people, experts say.

“We’ve got about a billion dollars that are potentially hanging in the balance over the next 10 years,” Mississippi Hospital Association President Richard Roberson said Wednesday during a panel discussion at his organization’s headquarters.

“If folks were being honest, the entire system depends on those rural hospitals,” he said.

Mississippi’s uninsured population could increase by 160,000 people as a combined result of the new law and the expiration of Biden-era enhanced subsidies that made marketplace insurance affordable – and which Trump is not expected to renew – according to KFF, a health policy research group.

That could make things even worse for those who are left on the marketplace plans.

“Younger, healthier people are going to leave the risk pool, and that’s going to mean it’s more expensive to insure the patients that remain,” said Lucy Dagneau, senior director of state and local campaigns at the American Cancer Society.

Among the biggest changes facing Medicaid-eligible patients are stiffer eligibility requirements, including proof of work. The new law requires able-bodied adults ages 19 to 64 to work, do community service or attend an educational program at least 80 hours a month to qualify for, or keep, Medicaid coverage and federal food aid.

Opponents say qualified recipients could be stripped of benefits if they lose a job or fail to complete paperwork attesting to their time commitment.

Georgia became the case study for work requirements with a program called Pathways to Coverage, which was touted as a conservative alternative to Medicaid expansion.

Ironically, the 54-year-old mechanic chosen by Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp to be the face of the program got so fed up with the work requirements he went from praising the program on television to saying “I’m done with it” after his benefits were allegedly cancelled twice due to red tape.

Roberson sent several letters to Mississippi’s congressional members in weeks leading up to the final vote on the sweeping federal legislation, sounding the alarm on what it would mean for hospitals and patients.

Among Roberson’s chief concerns is a change in the mechanism called state directed payments, which allows states to beef up Medicaid reimbursement rates – typically the lowest among insurance payors. The new law will reduce those enhanced rates to nearly as low as the Medicare rate, costing the state at least $500 million and putting rural hospitals in a bind, Roberson told Mississippi Today.

That change will happen over 10 years starting in 2028. That, in conjunction with the new law’s one-time payment program called the Rural Health Care Fund, means if the next few years look normal, it doesn’t mean Mississippi is safe, stakeholders warn.

“We’re going to have a sort of deceiving situation in Mississippi where we look a little flush with cash with the rural fund and the state directed payments in 2027 and 2028, and then all of a sudden our state directed payments start going down and that fund ends and then we’re going to start dipping,” said Leah Rupp Smith, vice president for policy and advocacy at the Mississippi Hospital Association.

Even with that buffer time, immediate changes are on the horizon for health care in Mississippi because of fear and uncertainty around ever-changing rules.

“Hospitals can’t budget when we have these one-off programs that start and stop and the rules change – and there’s a cost to administering a program like this,” Smith said.

Since hospitals are major employers – and they also provide a sense of safety for incoming businesses – their closure, especially in rural areas, affects not just patients but local economies and communities.

U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson is the only Democrat in Mississippi’s congressional delegation. He voted against the bill, while the state’s two Republican senators and three Republican House members voted for it. Thompson said in a statement that the new law does not bode well for the Delta, one of the poorest regions in the U.S.

“For my district, this means closed hospitals, nursing homes, families struggling to afford groceries, and educational opportunities deferred,” Thompson said. “Republicans’ priorities are very simple: tax cuts for (the) wealthy and nothing for the people who make this country work.”

While still colloquially referred to as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the name was changed by Democrats invoking a maneuver that has been used by lawmakers in both chambers to oppose a bill on principle.

“Democrats are forcing Republicans to delete their farcical bill name,” Senate Democratic Leader Charles Schumer of New York said in a statement. “Nothing about this bill is beautiful — it’s a betrayal to American families and it’s undeserving of such a stupid name.”

The law is expected to add at least $3.3 trillion to the nation’s debt over the next 10 years, according to the most recent estimate from the Congressional Budget Office.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Hospitals see danger in Medicaid spending cuts appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article reports on the negative impacts of a major federal tax and policy bill on Medicaid funding and rural hospitals in Mississippi. While it presents factual details and statements from stakeholders, the tone and framing emphasize the harmful consequences for vulnerable populations and health care access, aligning with concerns typically raised by center-left perspectives. The article highlights opposition by Democrats and critiques the bill’s priorities, particularly its effect on poor and rural communities, suggesting sympathy toward social safety net preservation. However, it maintains mostly factual reporting without overt partisan language, resulting in a moderate center-left bias.

Crooked Letter Sports Podcast

Podcast: The Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame Class of ’25

The MSHOF will induct eight new members on Aug 2. Rick Cleveland has covered them all and he and son Tyler talk about what makes them all special.

Stream all episodes here.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Podcast: The Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame Class of '25 appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Mississippi Today

‘You’re not going to be able to do that anymore’: Jackson police chief visits food kitchen to discuss new public sleeping, panhandling laws

Diners turned watchful eyes to the stage as Jackson Police Chief Joseph Wade took to the podium. He visited Stewpot Community Services during its daily free lunch hour Thursday to discuss new state laws, which took effect two days earlier, targeting Mississippians experiencing homelessness.

“I understand that you are going through some hard times right now. That’s why I’m here,” Wade said to the crowd. “I felt it was important to come out here and speak with you directly.”

Wade laid out the three bills that passed earlier this year: House Bill 1197, the “Safe Solicitation Act,” HB 1200, the “Real Property Owners Protection Act” and HB 1203, a bill that prohibits camping on public property.

“Sleeping and laying in public places, you’re not going to be able to do that anymore,” he said. “There’s a law that has been passed that you can’t just set up encampments on public or private properties where it’s a public nuisance, it’s a problem.”

The “Real Property Owners Protection Act,” authored by Rep. Brent Powell, R-Brandon, is a bill that expedites the process of removing squatters. The “Safe Solicitation Act,” authored by Rep. Shanda Yates, I-Jackson, requires a permit for panhandling and allows people to be charged with a misdemeanor if they violate this law. The offense is punishable by a fine not to exceed $300 and an offender could face up to six months in jail. Wade said he’s currently working with his legal department to determine the best strategy for creating and issuing permits.

“We’re going to navigate these legal challenges, get some interpretations, not only from our legal department, but the Attorney General’s office to ensure that we are doing it legally and lawfully, because I understand that these are citizens,” he said. “I understand that they deserve to be treated with respect, and I understand that we are going to do this without violating their constitutional rights.”

Wade said the Jackson Police Department is steadily fielding reports of squatters in abandoned properties and the law change gives officers new power to remove them more quickly. The added challenge? Figuring out what to do with a person’s belongings.

“These people are carrying around what they own, but we are not a repository for all of their stuff,” he said. “So, when we make that arrest, we’ve got to have a strategic plan as to what we do with their stuff.”

Wade said there needs to be a deeper conversation around the issues that lead someone to becoming homeless.

“A lot of people that we’re running across that are homeless are also suffering from medical conditions, mental health issues, and they’re also suffering from drug addiction and substance abuse. We’ve got to have a strategic approach, but we also can’t log jam our jail down in Raymond,” Wade said.

He estimates that more than 800 people are currently incarcerated at the Raymond Detention Center, and any increase could strain the system as the laws continue to be enforced.

“I think there’s layers that we have to work through, there’s hurdles that we are going to overcome, but we’ve got to make sure that we do it and make sure that my team and JPD is consistent in how we enforce these laws,” Wade said.

Diners applauded Wade after he spoke, in between bites of fried chicken, salad, corn and 4th of July-themed packaged cakes. Wade offered to answer questions, but no one asked any.

Rev. Jill Buckley, executive director of Stewpot, said that the legislation is a good tool to address issues around homelessness and community needs. She doesn’t want to see people who are homeless be criminalized, but she also wants communities to be safe.

“I support people’s right to self determine, and we can’t impose our choices on other people, but there are some cases in which that impinges on community safety, and so to the extent that anyone who is camping or panhandling or squatting and is a danger to themselves and others, of course, I fully support that kind of law. I don’t support homelessness being criminalized as such,” Buckley said.

Many of the people Wade addressed while they ate Thursday said they have housing, don’t panhandle, and shouldn’t be directly impacted by the legislation. But Marcus Willis, 42, said it would make more sense if elected officials wanted to combat the negative impacts of homelessness that they help more people secure employment.

“There ain’t enough jobs,” said Willis, who was having lunch with his girlfriend Amber Ivy.

The two live in an apartment together nearby on Capitol Street, where Ivy landed after her mother, whom Ivy had been living with, suffered a stroke and lost the property. Similarly, Willis started coming to eat at Stewpot after his grandmother, whose house he used to visit for lunch, passed away.

Willis holds odd jobs – cutting grass, home and auto repair – so the income is inconsistent, and every opportunity for stable employment he said he’s found is outside of Jackson in the suburbs. The couple doesn’t have a car.

Making rent every month usually depends on their ability to find someone to help chip in, said Ivy, who is in recovery from substance abuse. She said she’s watched problems surrounding homelessness grow over the years in Jackson. Ivy grew up near Stewpot and has lived in various neighborhoods across the city – except for the times she moved out of state when things got too rough.

“There was just moments where I just had to leave,” Ivy said. “Sometimes if you hit a slump here, there’s almost no way for you to get out of it.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post 'You're not going to be able to do that anymore': Jackson police chief visits food kitchen to discuss new public sleeping, panhandling laws appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Right

This article primarily reports on new laws in Jackson, Mississippi, targeting public sleeping, panhandling, and squatting, focusing on statements by Police Chief Joseph Wade and community perspectives. The coverage presents the legislative measures—authored by Republican and independent lawmakers—with a tone that emphasizes law enforcement challenges and community safety, reflecting a conservative approach to homelessness as a public order issue. While it includes voices concerned about criminalization and the need for social support, the overall framing centers on law enforcement and property protection. The article maintains factual reporting without overt editorializing but leans slightly toward a center-right perspective by highlighting legal enforcement as a solution.

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

Real-life Uncle Sam's descendants live in Arkansas

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed5 days ago

'Big Beautiful Bill' already felt at Georgia state parks | FOX 5 News

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days ago

LOFT report uncovers what led to multi-million dollar budget shortfall

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

Alabama schools to lose $68 million in federal grants under Trump freeze

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

Celebrate St. Louis returns with new Superman-themed drone show

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days ago

Tropical Depression Three to bring rain, gusty winds to the CSRA this Fourth of July weekend

-

The Center Square4 days ago

Here are the violent criminals Judge Murphy tried to block from deportation | Massachusetts

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days ago

What’s being explored at the ‘Pit of Despair?’ Razor wire OK atop fence within city limits? Mystery pile of dirt along I-26? • Asheville Watchdog