Kelly Lambert, CC BY-ND

Kelly Lambert, University of Richmond

We crafted our first rodent car from a plastic cereal container. After trial and error, my colleagues and I found that rats could learn to drive forward by grasping a small wire that acted like a gas pedal. Before long, they were steering with surprising precision to reach a Froot Loop treat.

As expected, rats housed in enriched environments – complete with toys, space and companions – learned to drive faster than those in standard cages. This finding supported the idea that complex environments enhance neuroplasticity: the brain’s ability to change across the lifespan in response to environmental demands.

After we published our research, the story of driving rats went viral in the media. The project continues in my lab with new, improved rat-operated vehicles, or ROVs, designed by robotics professor John McManus and his students. These upgraded electrical ROVs – featuring rat-proof wiring, indestructible tires and ergonomic driving levers – are akin to a rodent version of Tesla’s Cybertruck.

As a neuroscientist who advocates for housing and testing laboratory animals in natural habitats, I’ve found it amusing to see how far we’ve strayed from my lab practices with this project. Rats typically prefer dirt, sticks and rocks over plastic objects. Now, we had them driving cars.

But humans didn’t evolve to drive either. Although our ancient ancestors didn’t have cars, they had flexible brains that enabled them to acquire new skills – fire, language, stone tools and agriculture. And some time after the invention of the wheel, humans made cars.

Although cars made for rats are far from anything they would encounter in the wild, we believed that driving represented an interesting way to study how rodents acquire new skills. Unexpectedly, we found that the rats had an intense motivation for their driving training, often jumping into the car and revving the “lever engine” before their vehicle hit the road. Why was that?

The new destination of joy

Concepts from introductory psychology textbooks took on a new, hands-on dimension in our rodent driving laboratory. Building on foundational learning approaches such as operant conditioning, which reinforces targeted behavior through strategic incentives, we trained the rats step-by-step in their driver’s ed programs.

Initially, they learned basic movements, such as climbing into the car and pressing a lever. But with practice, these simple actions evolved into more complex behaviors, such as steering the car toward a specific destination.

The rats also taught me something profound one morning during the pandemic.

It was the summer of 2020, a period marked by emotional isolation for almost everyone on the planet, even laboratory rats. When I walked into the lab, I noticed something unusual: The three driving-trained rats eagerly ran to the side of the cage, jumping up like my dog does when asked if he wants to take a walk.

Had the rats always done this and I just hadn’t noticed? Were they just eager for a Froot Loop, or anticipating the drive itself? Whatever the case, they appeared to be feeling something positive – perhaps excitement and anticipation.

Behaviors associated with positive experiences are associated with joy in humans, but what about rats? Was I seeing something akin to joy in a rat? Maybe so, considering that neuroscience research is increasingly suggesting that joy and positive emotions play a critical role in the health of both human and nonhuman animals.

With that, my team and I shifted focus from topics such as how chronic stress influences brains to how positive events – and anticipation for these events – shape neural functions.

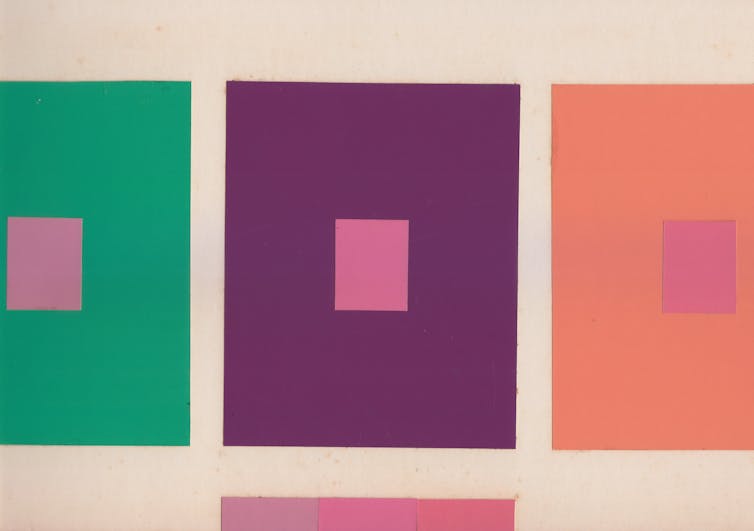

Kelly Lambert, CC BY-ND

Working with postdoctoral fellow Kitty Hartvigsen, I designed a new protocol that used waiting periods to ramp up anticipation before a positive event. Bringing Pavlovian conditioning into the mix, rats had to wait 15 minutes after a Lego block was placed in their cage before they received a Froot Loop. They also had to wait in their transport cage for a few minutes before entering Rat Park, their play area. We also added challenges, such as making them shell sunflower seeds before eating.

This became our Wait For It research program. We dubbed this new line of study UPERs – unpredictable positive experience responses – where rats were trained to wait for rewards. In contrast, control rats received their rewards immediately. After about a month of training, we expose the rats to different tests to determine how waiting for positive experiences affects how they learn and behave. We’re currently peering into their brains to map the neural footprint of extended positive experiences.

Preliminary results suggest that rats required to wait for their rewards show signs of shifting from a pessimistic cognitive style to an optimistic one in a test designed to measure rodent optimism. They performed better on cognitive tasks and were bolder in their problem-solving strategies. We linked this program to our lab’s broader interest in behaviorceuticals, a term I coined to suggest that experiences can alter brain chemistry similarly to pharmaceuticals.

This research provides further support of how anticipation can reinforce behavior. Previous work with lab rats has shown that rats pressing a bar for cocaine – a stimulant that increases dopamine activation – already experience a surge of dopamine as they anticipate a dose of cocaine.

The tale of rat tails

It wasn’t just the effects of anticipation on rat behavior that caught our attention. One day, a student noticed something strange: One of the rats in the group trained to expect positive experiences had its tail straight up with a crook at the end, resembling the handle of an old-fashioned umbrella.

I had never seen this in my decades of working with rats. Reviewing the video footage, we found that the rats trained to anticipate positive experiences were more likely to hold their tails high than untrained rats. But what, exactly, did this mean?

Kelly Lambert, CC BY-SA

Curious, I posted a picture of the behavior on social media. Fellow neuroscientists identified this as a gentler form of what’s called Straub tail, typically seen in rats given the opioid morphine. This S-shaped curl is also linked to dopamine. When dopamine is blocked, the Straub tail behavior subsides.

Natural forms of opiates and dopamine – key players in brain pathways that diminish pain and enhance reward – seem to be telltale ingredients of the elevated tails in our anticipation training program. Observing tail posture in rats adds a new layer to our understanding of rat emotional expression, reminding us that emotions are expressed throughout the entire body.

While we can’t directly ask rats whether they like to drive, we devised a behavioral test to assess their motivation to drive. This time, instead of only giving rats the option of driving to the Froot Loop Tree, they could also make a shorter journey on foot – or paw, in this case.

Surprisingly, two of the three rats chose to take the less efficient path of turning away from the reward and running to the car to drive to their Froot Loop destination. This response suggests that the rats enjoy both the journey and the rewarding destination.

Rat lessons on enjoying the journey

We’re not the only team investigating positive emotions in animals.

Neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp famously tickled rats, demonstrating their capacity for joy.

Research has also shown that desirable low-stress rat environments retune their brains’ reward circuits, such as the nucleus accumbens. When animals are housed in their favored environments, the area of the nucleus accumbens that responds to appetitive experiences expands. Alternatively, when rats are housed in stressful contexts, the fear-generating zones of their nucleus accumbens expand. It is as if the brain is a piano the environment can tune.

Neuroscientist Curt Richter also made the case for rats having hope. In a study that wouldn’t be permitted today, rats swam in glass cylinders filled with water, eventually drowning from exhaustion if they weren’t rescued. Lab rats frequently handled by humans swam for hours to days. Wild rats gave up after just a few minutes. If the wild rats were briefly rescued, however, their survival time extended dramatically, sometimes by days. It seemed that being rescued gave the rats hope and spurred them on.

The driving rats project has opened new and unexpected doors in my behavioral neuroscience research lab. While it’s vital to study negative emotions such as fear and stress, positive experiences also shape the brain in significant ways.

As animals – human or otherwise – navigate the unpredictability of life, anticipating positive experiences helps drive a persistence to keep searching for life’s rewards. In a world of immediate gratification, these rats offer insights into the neural principles guiding everyday behavior. Rather than pushing buttons for instant rewards, they remind us that planning, anticipating and enjoying the ride may be key to a healthy brain. That’s a lesson my lab rats have taught me well.![]()

Kelly Lambert, Professor of Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Richmond

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.