Mississippi Today

ICE agents detain immigrants during routine check-ins, advocates say

ICE agents detain immigrants during routine check-ins, advocates say

Within the past several weeks, at least four people have been detained after routine check-in appointments at the Pearl U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement office, local advocates say.

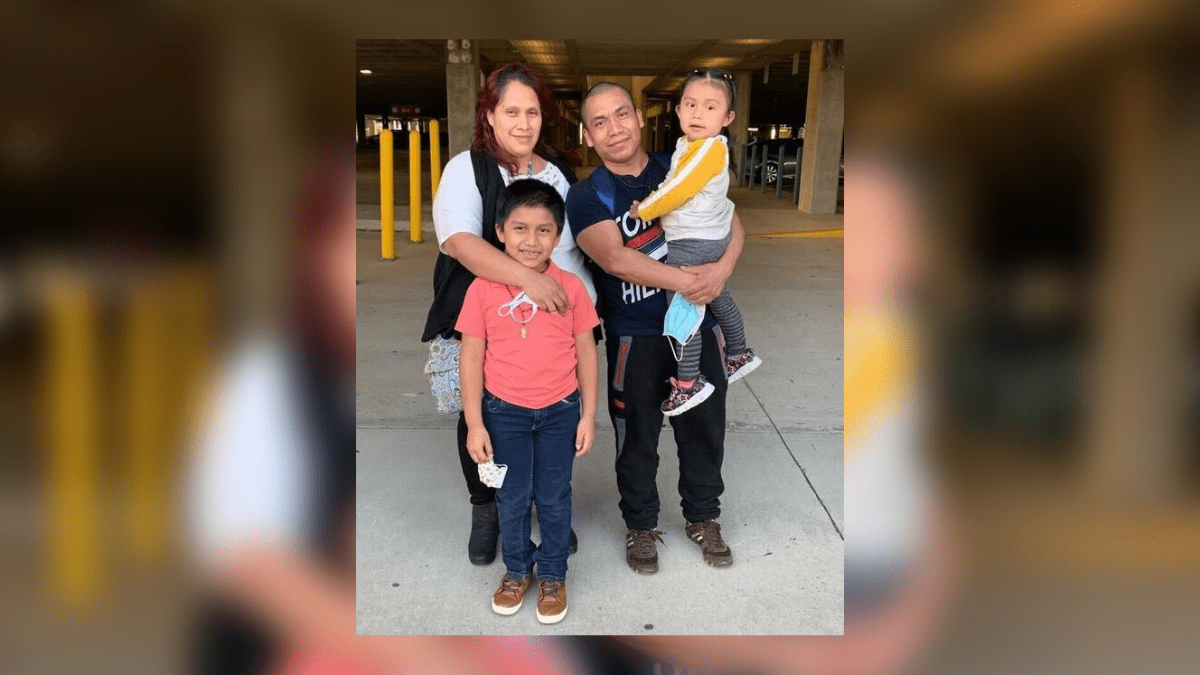

The most recent was Carthage resident Baldomero Orozco Juarez, who is Guatemalan and has been living and working in Mississippi for 14 years. He was detained April 12 during a scheduled check-in, said Lorena Quiroz, executive director of the Immigrant Alliance for Justice and Equity.

Since then, he has been at the LaSalle Detention Center in Jena, Louisiana, which is where many Mississippi immigrants are sent, she said.

Orozco Juarez was deported after the 2019 ICE chicken plant raids, reentered the country and spent over a year in a detention center in Texas until the agency approved his probationary release, she said.

“It was already determined you can do that,” Quiroz said about Juarez awaiting his court date from home instead of in a detention center.

Nearly two weeks ago, she and a dozen other community advocates went to the Pearl ICE office to ask for answers about Orozco Juarez’s detention but were not told much. Demonstrators were asked to leave the building and local police were called as they stood outside.

With probationary release, Orozco Juarez was able to obtain a work permit, driver’s license and a Social Security card, Quiroz said.

She said Orozco Juarez, who has been working, caring for his family and going to routine ICE check-ins, is not a flight risk. Before his recent detention, he had gone to three scheduled check-ins.

Orozco Juarez’s wife, Sylvia Garcia, came to the immigration office once she learned her husband had been detained. With translation from Quiroz, Garcia said it will be difficult without Orozco Juarez because she is injured and unable to work.

“They are separating our families without any reason,” Garcia said.

She and Juarez have two children, ages 5 and 9, who were born in Mississippi.

Dalaney Mecham, an immigration attorney in Gulfport, said officers have a lot of discretion when it comes to deciding whether to let someone into the country at the U.S.-Mexico border or whether to detain them during a check-in.

Due to changes with processing at the border within the past several years, the agency has started issuing paperwork for people to report to an ICE office so they can get a document called a “notice to appear,” which would include a time, date and location of their next immigration court date. Previously, people were issued a notice to appear at the border, Mecham said.

A clear picture of common arrests during check-ins in Mississippi and nationwide is not known. A spokesperson with ICE’s public affairs office in Washington D.C. did not respond to a request to access any data the agency keeps about arrests during check-ins, and data the agency does have online does not specify about these kinds of arrests.

ICE spokesman Nestor Yglesias said the agency makes decisions about who to place in custody on a case-by-case basis regardless of nationality based on policy and factors of each case.

But Orozco Juarez has a documented history of disregarding immigration law, which contributed to his recent detention, he said.

“For the past two years, ICE afforded Mr. [Orozco Juarez] the opportunity to be compliant with his removal order by planning his own return to Guatemala,” Yglesias said in the statement. “He will remain in ICE custody pending his removal from the country.”

The Immigrant Alliance for Justice and Equity knows of three other people who have been detained in recent weeks.

ICE had given those people a smartphone with an app that allows the agency to monitor whether they are staying in the area by taking a picture of themselves or answering a phone call when requested, Quiroz said.

The immigrants received an email saying the app was closed and they needed to come to the ICE office, she said. When they called the office back to learn when to come, there was no answer. They went to the office to check in on their appointment and were held without explanation.

All three of the detained people are Nicaraguan immigrants who are seeking asylum due to political instability and violence in their country, Quiroz said. They had been in the United States for a year or less, and one was transferred to the Jena detention facility.

Orozco Juarez could be detained until his trial, which could take years, but the Immigrant Alliance for Justice and Equity and his attorney are hoping to bring him home.

Most of the immigration court proceedings for the area are conducted in New Orleans.

The average wait time for a case in the New Orleans court is 709 days, which is nearly two years, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse immigration backlog tracker by Syracuse University. This wait time is about two months shorter than the national case wait time of 762 days.

As of January, there are an estimated 48,690 pending cases across all of Louisiana’s immigration courts, which include the largest in New Orleans and two smaller ones based in detention centers in Oakdale and Jena, according to the TRAC backlog tracker.

Mecham said some people he has represented have also been taken into custody during their routine ICE check-ins. He has noticed how people seek attorneys before their appointments because they are scared and have heard stories about others being detained during their check-ins.

“Not knowing if they are going to come home that day is scary, especially if you have kids and you’ve been here for a while,” Mecham said.

Similar to the experience of Orozco Juarez at the Pearl office, Mecham’s client, Lenin Ramirez, went to an ICE check-in in August 2021 in New Orleans, and that resulted in a two-month detention in a Louisiana detention center.

Mecham called the immigration office to ask why his client was detained, especially since Ramirez, who lives in Mobile, was seeking asylum from Nicaragua. The officer said he was detained because he entered the country without authorization, Mecham said.

Mecham was able to get Ramirez out by going first to the New Orleans ICE field office, then at the federal level through ICE’s ombudsman and the Department of Homeland Security, which reviewed Ramirez’s case and issued him a notice to appear with his scheduled court date.

Since Ramirez’s release, Mecham has filed Ramirez’s asylum application and they are waiting for his next court date in July 2025.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

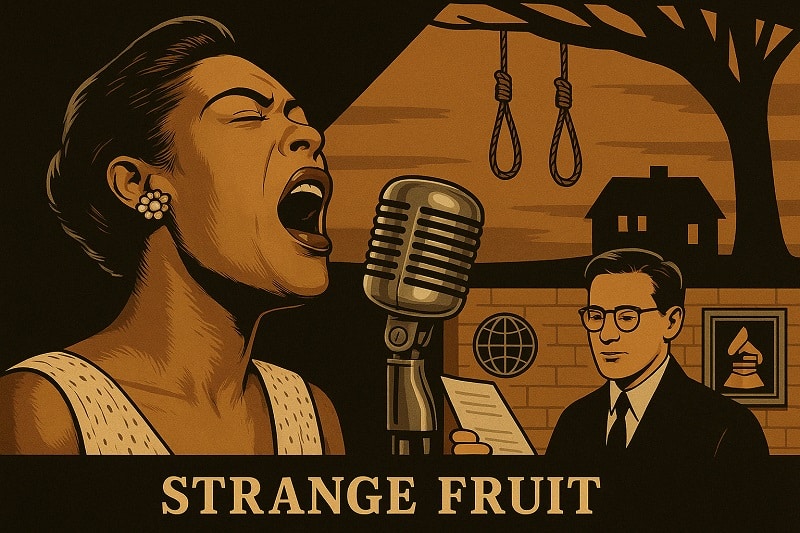

On this day in 1939, Billie Holiday recorded ‘Strange Fruit’

April 20, 1939

Legendary jazz singer Billie Holiday stepped into a Fifth Avenue studio and recorded “Strange Fruit,” a song written by Jewish civil rights activist Abel Meeropol, a high school English teacher upset about the lynchings of Black Americans — more than 6,400 between 1865 and 1950.

Meeropol and his wife had adopted the sons of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were orphaned after their parents’ executions for espionage.

Holiday was drawn to the song, which reminded her of her father, who died when a hospital refused to treat him because he was Black. Weeks earlier, she had sung it for the first time at the Café Society in New York City. When she finished, she didn’t hear a sound.

“Then a lone person began to clap nervously,” she wrote in her memoir. “Then suddenly everybody was clapping.”

The song sold more than a million copies, and jazz writer Leonard Feather called it “the first significant protest in words and music, the first unmuted cry against racism.”

After her 1959 death, both she and the song went into the Grammy Hall of Fame, Time magazine called “Strange Fruit” the song of the century, and the British music publication Q included it among “10 songs that actually changed the world.”

David Margolick traces the tune’s journey through history in his book, “Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday and the Biography of a Song.” Andra Day won a Golden Globe for her portrayal of Holiday in the film, “The United States vs. Billie Holiday.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Mississippians are asked to vote more often than people in most other states

Not long after many Mississippi families celebrate Easter, they will be returning to the polls to vote in municipal party runoff elections.

The party runoff is April 22.

A year does not pass when there is not a significant election in the state. Mississippians have the opportunity to go to the polls more than voters in most — if not all — states.

In Mississippi, do not worry if your candidate loses because odds are it will not be long before you get to pick another candidate and vote in another election.

Mississippians go to the polls so much because it is one of only five states nationwide where the elections for governor and other statewide and local offices are held in odd years. In Mississippi, Kentucky and Louisiana, the election for governor and other statewide posts are held the year after the federal midterm elections. For those who might be confused by all the election lingo, the federal midterms are the elections held two years after the presidential election. All 435 members of the U.S. House and one-third of the membership of the U.S. Senate are up for election during every midterm. In Mississippi, there also are important judicial elections that coincide with the federal midterms.

Then the following year after the midterms, Mississippians are asked to go back to the polls to elect a governor, the seven other statewide offices and various other local and district posts.

Two states — Virginia and New Jersey — are electing governors and other state and local officials this year, the year after the presidential election.

The elections in New Jersey and Virginia are normally viewed as a bellwether of how the incumbent president is doing since they are the first statewide elections after the presidential election that was held the previous year. The elections in Virginia and New Jersey, for example, were viewed as a bad omen in 2021 for then-President Joe Biden and the Democrats since the Republican in the swing state of Virginia won the Governor’s Mansion and the Democrats won a closer-than-expected election for governor in the blue state of New Jersey.

With the exception of Mississippi, Louisiana, Kentucky, Virginia and New Jersey, all other states elect most of their state officials such as governor, legislators and local officials during even years — either to coincide with the federal midterms or the presidential elections.

And in Mississippi, to ensure that the democratic process is never too far out of sight and mind, most of the state’s roughly 300 municipalities hold elections in the other odd year of the four-year election cycle — this year.

The municipal election impacts many though not all Mississippians. Country dwellers will have no reason to go to the polls this year except for a few special elections. But in most Mississippi municipalities, the offices for mayor and city council/board of aldermen are up for election this year.

Jackson, the state’s largest and capital city, has perhaps the most high profile runoff election in which state Sen. John Horhn is challenging incumbent Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba in the Democratic primary.

Mississippi has been electing its governors in odd years for a long time. The 1890 Mississippi Constitution set the election for governor for 1895 and “every four years thereafter.”

There is an argument that the constant elections in Mississippi wears out voters, creating apathy resulting in lower voter turnout compared to some other states.

Turnout in presidential elections is normally lower in Mississippi than the nation as a whole. In 2024, despite the strong support for Republican Donald Trump in the state, 57.5% of registered voters went to the polls in Mississippi compared to the national average of 64%, according to the United States Elections Project.

In addition, Mississippi Today political reporter Taylor Vance theorizes that the odd year elections for state and local officials prolonged the political control for Mississippi Democrats. By 1948, Mississippians had started to vote for a candidate other than the Democrat for president. Mississippians began to vote for other candidates — first third party candidates and then Republicans — because of the national Democratic Party’s support of civil rights.

But because state elections were in odd years, it was easier for Mississippi Democrats to distance themselves from the national Democrats who were not on the ballot and win in state and local races.

In the modern Mississippi political environment, though, Republicans win most years — odd or even, state or federal elections. But Democrats will fare better this year in municipal elections than they do in most other contests in Mississippi, where the elections come fast and often.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mississippi Today

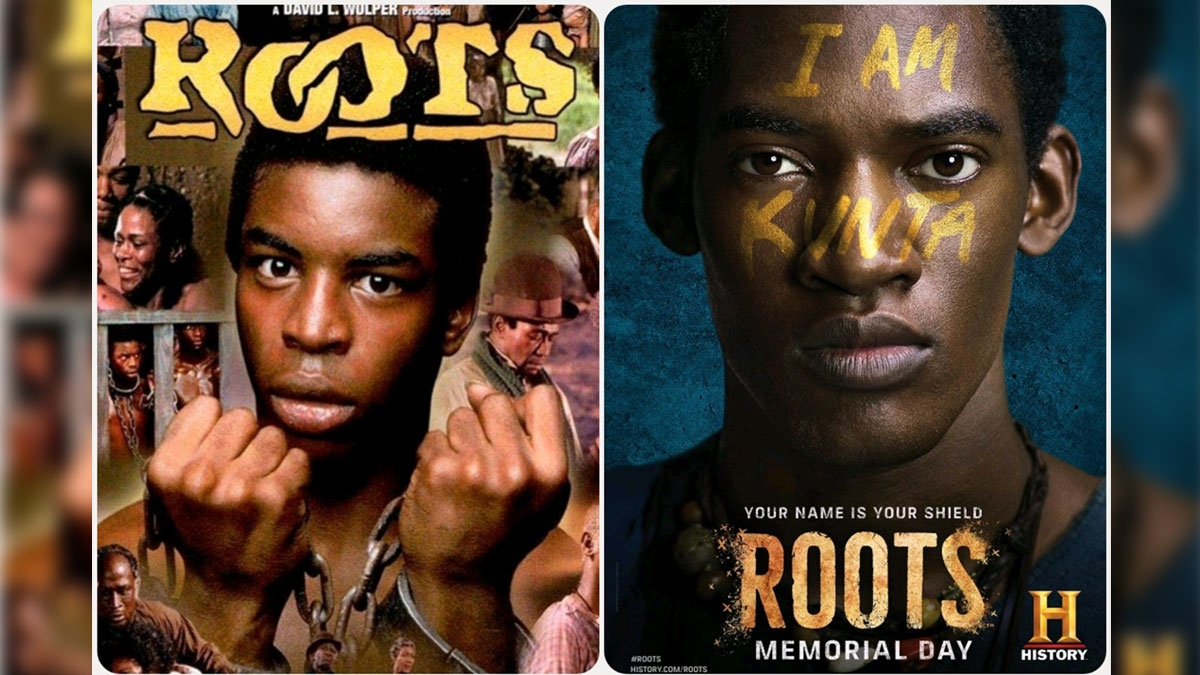

On this day in 1977, Alex Haley awarded Pulitzer for ‘Roots’

April 19, 1977

Alex Haley was awarded a special Pulitzer Prize for “Roots,” which was also adapted for television.

Network executives worried that the depiction of the brutality of the slave experience might scare away viewers. Instead, 130 million Americans watched the epic miniseries, which meant that 85% of U.S. households watched the program.

The miniseries received 36 Emmy nominations and won nine. In 2016, the History Channel, Lifetime and A&E remade the miniseries, which won critical acclaim and received eight Emmy nominations.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoFoley man wins Race to the Finish as Kyle Larson gets first win of 2025 Xfinity Series at Bristol

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days agoFederal appeals court upholds ruling against Alabama panhandling laws

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed3 days agoDrivers brace for upcoming I-70 construction, slowdowns

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days agoFDA warns about fake Ozempic, how to spot it

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed5 days agoLieutenant governor race heats up with early fundraising surge | Virginia

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days agoAbandoned property causing issues in Pine Lawn, neighbor demands action

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed4 days agoThursday April 17, 2025 TIMELINE: Severe storms Friday

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days agoTwo dead, 9 injured after shooting at Conway park | What we know