Conspiracy theories can muddle people’s thinking.

H. Colleen Sinclair, Louisiana State University

Conspiracy theories are everywhere, and they can involve just about anything.

People believe false conspiracy theories for a wide range of reasons – including the fact that there are real conspiracies, like efforts by the Sackler family to profit by concealing the addictiveness of oxycontin at the cost of countless American lives.

The extreme consequences of unfounded conspiratorial beliefs could be seen on the staircases of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, and in the self-immolation of a protestor outside the courthouse holding the latest Trump trial.

But if hidden forces really are at work in the world, how is someone to know what’s really going on?

That’s where my research comes in; I’m a social psychologist who studies misleading narratives. Here are some ways to vet a claim you’ve seen or heard.

Step 1: Seek out the evidence

Real conspiracies have been confirmed because there was evidence. For instance, in the allegations dating back to the 1990s that tobacco companies knew cigarettes were dangerous and kept that information secret to make money, scientific studies showed problematic links between tobacco and cancer. Court cases unearthed corporate documents with internal memos showing what executives knew and when. Investigative journalists revealed efforts to hide that information. Doctors explained the effects on their patients. Internal whistleblowers sounded the alarm.

But unfounded conspiracy theories reveal their lack of evidence and substitute instead several elements that should be red flags for skeptics:

-

Dismissing traditional sources of evidence, claiming they are in on the plot.

-

Claiming that missing information is because someone is hiding it, even though it’s common that not all facts are known completely for some time after an event.

-

Attacking apparent inconsistencies as evidence of lies.

-

Overinterpreting ambiguity as evidence: A flying object may be unidentified – but that’s different from identifying it as an alien spaceship.

-

Using anecdotes – especially vaguely attributed ones – in place of evidence, such as “people are saying” such-and-such or “my cousin’s friend experienced” something.

-

Attributing knowledge to secret messages that only a select few can grasp – rather than evidence that’s plain and clear to all.

Step 2: Test the allegation

Often, a conspiracy theorist presents only evidence that confirms their idea. Rarely do they put their idea to the tests of logic, reasoning and critical thinking.

While they may say they do research, they typically do not apply the scientific method. Specifically, they don’t actually try to prove themselves wrong.

So a skeptic can follow the method scientists use when they do research: Think about what evidence would contradict the explanation – and then go looking for that evidence.

Sometimes that effort will yield confirmation that the explanation is correct. And sometimes not. Like a scientist, ask yourself: What would it take for you to believe your perception was wrong?

Step 3: Watch out for tangled webs

When theories claim large groups of people are perpetrating wide-ranging activities over a long period of time, that’s another red flag.

Confirmed conspiracies typically involve small, isolated groups, like the top echelon of a company or a single terrorist cell. Even the alliance among tobacco companies to hide their products’ danger was confined to those at the top, who made decisions and enlisted paid scientists and ad agencies to spread their messages.

False conspiracies tend to implicate wide swaths of people, such as world leaders, mainstream media outlets, the global scientific community, the Hollywood entertainment industry and interconnected government agencies.

The online manifesto of Max Azzarello – the man who self-immolated on the steps of a New York courthouse in April 2024– railed against a conspiracy allegedly including every president since Bill Clinton, sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, even the writers of “The Simpsons.”

Remember that the more people who supposedly know a secret, the harder it is to keep.

Step 4: Look for a motive

Confirmed conspiracies tell stories about why a group of people acted as they did and what they hoped to gain. Dubious conspiracies involve a lot of accusations or just questions without examining what real benefit the conspiracy nets the conspirators, especially when factoring in the costs.

For instance, what purpose would NASA have to lie about the existence of Finland?

Be particularly suspicious when conspiracies allege an “agenda” being perpetrated by an entire sociodemographic, which is often a marginalized group, such as a “gay agenda” or “Muslim agenda.”

Also look to see whether those spreading the conspiracy theories have something to gain. For example, scholarly research has identified the 12 people who are the primary sources of false claims about vaccinations. The researchers also found that those people profit from making those claims.

Step 5: Seek the source of the allegations

If you can’t figure out who is at the root of a conspiracy allegation and thus how they came to know what they claim, that is another red flag. Some people say they have to remain anonymous because the conspiracists will take revenge for revealing information. But even so, a conspiracy can usually be tracked back to its source – maybe a social media account, even an anonymous one.

Over time, anonymous sources either come forward or are revealed. For instance, years after the Watergate scandal took down Richard Nixon’s presidency, a key inside source known as “Deep Throat” was revealed to be Mark Felt, who had been a high-level FBI official in the early 1970s.

Even the notorious “Q” at the heart of the QAnon conspiracy cult has been identified, and not by government investigators chasing leaks of national secrets. Surprise! Q is not the high-level official some people believed.

Reliable sources are transparent.

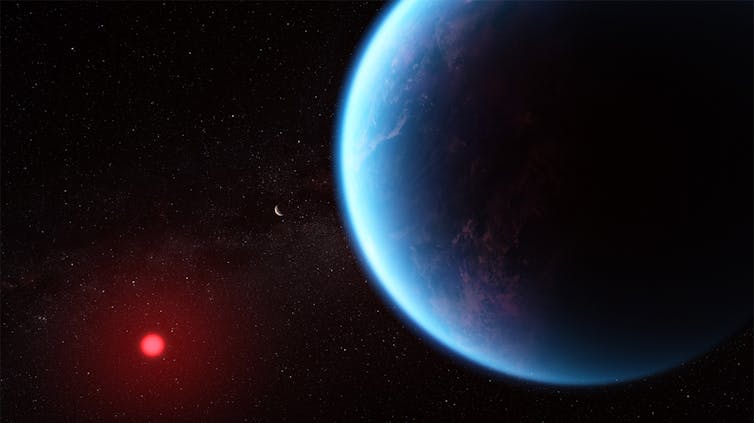

Step 6: Beware the supernatural

Some conspiracy theories – though none that have been proven – involve paranormal, alien, demonic or other supernatural forces. People alive in the 1980s and 1990s might remember the public fear that satanic cults were abusing and sacrificing children. That idea never disappeared entirely.

And around the same time, perhaps inspired by the TV series “V,” some Americans began to believe in lizard people. It may seem harmless to keep hoping for evidence of Bigfoot, but the person who detonated a bomb in downtown Nashville on Dec. 25, 2020, apparently believed lizard people ran the Earth.

The closer the conspiracy is to science fiction, the closer it is to just being fiction.

Step 7: Look for other warning signs

There are other red flags too, like the use of prejudicial tropes about the group allegedly behind the conspiracy, particularly antisemitic allegations.

But rather than doing the work to really examine their conspiratorial beliefs, believers often choose to write off the skeptics as fools or as also being in on it – whatever “it” may be.

Ultimately, that’s part of the allure of conspiracy theories. It is easier to dismiss criticism than to admit you might be wrong.![]()

H. Colleen Sinclair, Associate Research Professor of Social Psychology, Louisiana State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.